Background and Objectives: Patients in many countries face poor access to specialist care. Electronic consultation (eConsult) improves access by allowing primary care providers (PCPs) and specialists to communicate electronically. As more countries adopt eConsult services, there has been growing interest in leveraging them as educational tools. Our study aimed to assess PCPs’ perspectives on eConsult’s ability to improve collegiality between providers and serve as an educational tool.

Methods: We conducted a qualitative content analysis of free-text comments left by PCPs using the Champlain BASE eConsult service based in Eastern Ontario, Canada. All responses provided between January 1, 2015 and January 31, 2017 that mentioned education or collegiality were included.

Results: PCPs completed 16,712 closeout surveys during the study period, of which 3,601 (22%) included free-text comments. Of these, 223 (6%) included references to education or collegiality. Three prominent themes emerged from the data: building provider relationships, teaching incorporated into answer, and prompting further learning.

Conclusions: PCPs described eConsult’s ability to foster stronger relationships with specialists, deliver responses that provided teaching in multiple areas of their practice, and support further learning that extended beyond the case at hand and into their overall practice. The Champlain BASE eConsult service has educational value for providers. Further study is underway to explore how questions and replies submitted through eConsult can be used to facilitate reflective learning and promote feedback to providers.

Patients in many countries face poor access to specialist care.1-3 In Canada, patients face wait times for specialist care exceeding those of most developed countries. A 2016 Commonwealth Fund survey of 11 countries found that 56% of Canadians wait more than 4 weeks for specialist appointments, compared to an international average of 36%.2 The United States fared better, though numerous studies have identified serious inequities in access to various specialty services, particularly for patients who live in low-income communities or lack private insurance.1,3 This issue has serious consequences, causing frustration for providers, increased costs for the health system, and poorer health outcomes for patients.4-7 New approaches are needed to reduce wait times and improve access. Electronic consultation (eConsult) offers a promising solution.

Several jurisdictions in the United States, Canada, and Europe have adopted eConsult services with encouraging results.8,9 A growing body of literature has demonstrated eConsult’s ability to improve timely access to specialist advice,8,9 increase patient and provider satisfaction,10,11 improve health outcomes,12 and reduce costs.13,14 Furthermore, recent studies have shown a growing interest in eConsult’s potential to increase collegiality between providers and support continuing medical education.15-17

In Jean Lave’s situated learning theory, he states that all learning is embedded within activity, context, and culture. He emphasizes that learning is most effective within a “community of practice.”18 As the learner moves from the periphery of the community to the center, they become more engaged within the culture and eventually assume the role of an expert.18-20 If we consider this in the context of the eConsult service, we can theorize that providers’ interactions within the eConsult platform create a unique learning community that can situate, engage, and transform a learner’s knowledge. Building on situated learning is the theory of connectivism, which views a learning community as a node in a much larger learning network.21

In this study, we examined survey responses from PCPs enrolled with the Champlain Building Access to Specialists Through eConsultation (BASE) eConsult service. Our goal was to assess PCPs’ perspectives on eConsult’s ability to improve collegiality between providers and serve as an educational tool.

Design

We conducted a qualitative content analysis of free-text responses made by PCPs during a mandatory closeout survey at the end of each eConsult interaction. All responses pertaining to educational value or collegiality were included.

Setting

The eConsult Service is located in the Champlain Local Health Integration Network (LHIN), a health region in Eastern Ontario, Canada. The region has a population of approximately 1.2 million people, with half residing in the region’s major metropolitan area (Ottawa) and half in the surrounding rural districts up to 2 hours away by car.

The eConsult Service

The Champlain BASE eConsult service is a secure online application that links primary care providers (PCP) and specialists. First launched in the Champlain LHIN as a small proof of concept in 2010, the service became a full pilot in 2011 and has expanded across Ontario.22 PCPs log into the service using any device with a web browser, enter their question into a free-text field, attaching any files they deem relevant to the case (eg, images, test results), and select a target specialty from a drop-down menu. A case assigner allocates the case to a specialist from the chosen specialty, who responds with advice, a recommendation for a face-to-face referral, or a request for more information. Specialists are expected to reply within 1 week, though the median response time for the service is only 0.9 days.23 PCPs complete a survey at the conclusion of every eConsult case including an optional free text box that allows PCPs to leave any additional comments they may have.

Data Collection

Usage data and survey responses are collected automatically by the service. For the purposes of this study, we only included cases in which (1) PCPs opted to leave a free-text comment pertaining to reference to education or collegiality, and that (2) closed on or after January 1, 2015. This date was selected to avoid overlap with a previous thematic analysis that included free-text data from all surveys completed prior to 2015 and looked at PCPs’ responses more broadly.11

All participating PCPs have already provided consent for data collection and analysis. The data collection process is part of the original study protocol and has received approval from the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board (OHSN REB #2009848-01H).

Data Analysis

An initial coder (J.J.) reviewed all PCP comments left between January 1, 2015 and January 31, 2017. The coder selected all comments that pertained to education or collegiality. Relevance was determined by the presence of terms such as “collegial,” “teaching,” “education,” “learning,” etc. This process was conducted manually rather than through a search algorithm to allow for the inclusion of cases where issues of education or collegiality were discussed without reference to preselected key terms. The coder excluded all cases not selected in the initial parsing and imported the remaining cases into NVivo software to facilitate analysis.

Next, two coders (J.J. and T.A.) reviewed the cases independently and conducted a content analysis24 on the deidentified comments using NVivo software. Specifically, both analysts independently coded each comment using a word or phrase that captured the narrative feedback, and eventually distilled several recurring themes. This was done in three progressive analytical stages: initial (line-by-line coding), focused (preliminary recurring themes), and theoretical coding (finalize list of consolidated themes).25 Once themes had been identified, the reviewers met several times to discuss themes and recode the data until a framework evolved that both coders agreed upon. Disagreements about the data were resolved through discussion. Upon completion of the initial framework, the two coders reviewed the codebook independently, noting any mis-coded items or redundant or misplaced themes. They revised the codebook and presented to the research team, which included a primary care provider (C.L.), endocrinologist (E.K.), and academic researcher (D.A.) to ensure that both clinical and methodological perspectives were brought to the analysis.

The research team provided feedback and identified any disconfirming data. The team met several times to generate interpretive insights, and to guide the final framework. Review continued in an iterative process until the entire research team was satisfied with the codebook.

PCPs completed 16,712 closeout surveys during the study period, of which 3,601 (22%) included free-text comments. Of these, 223 (6%) included references to education or collegiality. The 223 comments that met inclusion criteria were submitted by 106 unique PCPs, of whom 60% were female, 96% were family physicians (vs 4% nurse practitioners), and 86% practiced in urban regions.

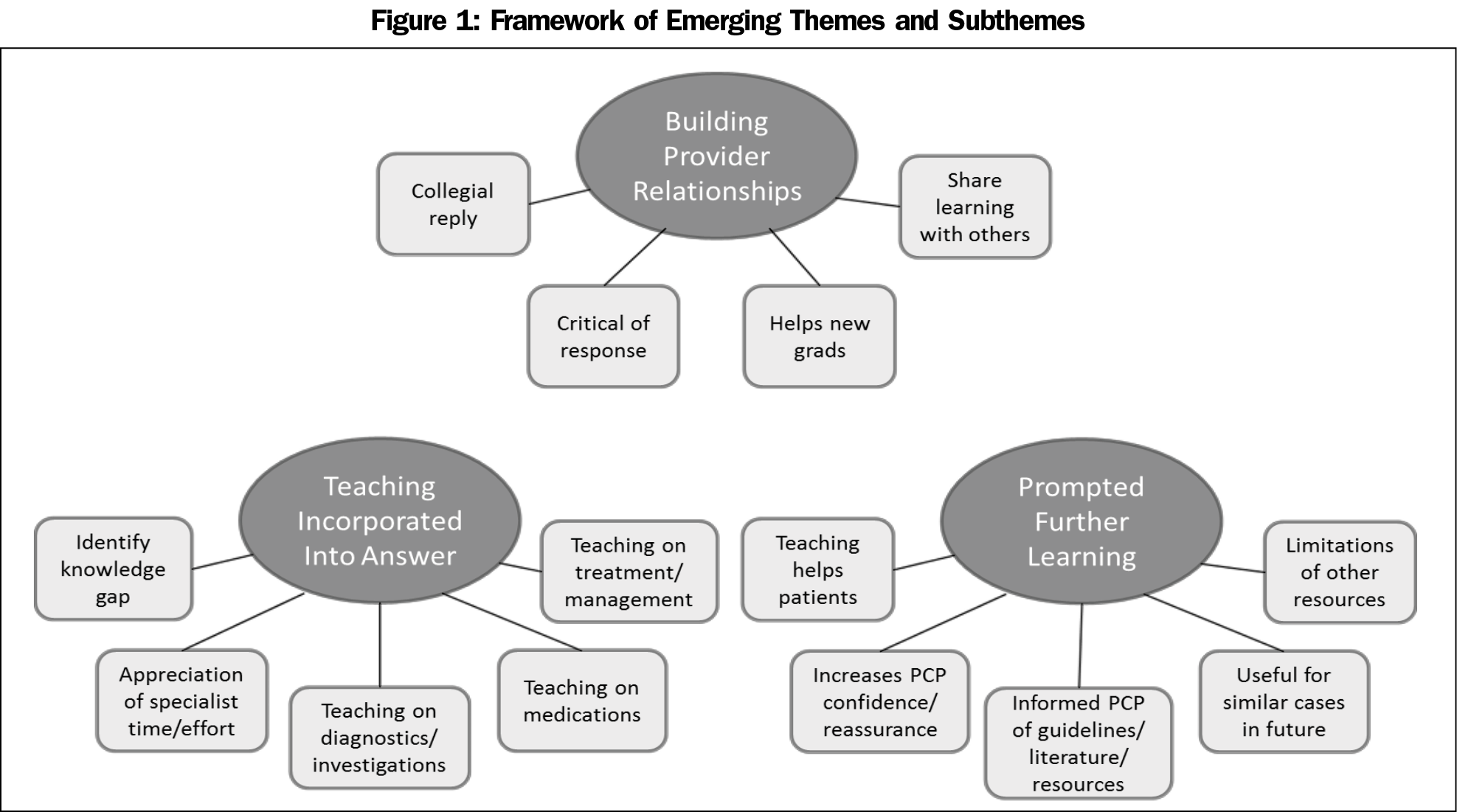

Upon completion of our analysis, three prominent themes emerged from the data: building provider relationships, teaching incorporated into answer, and prompting further learning (Figure 1).

Building Provider Relationships

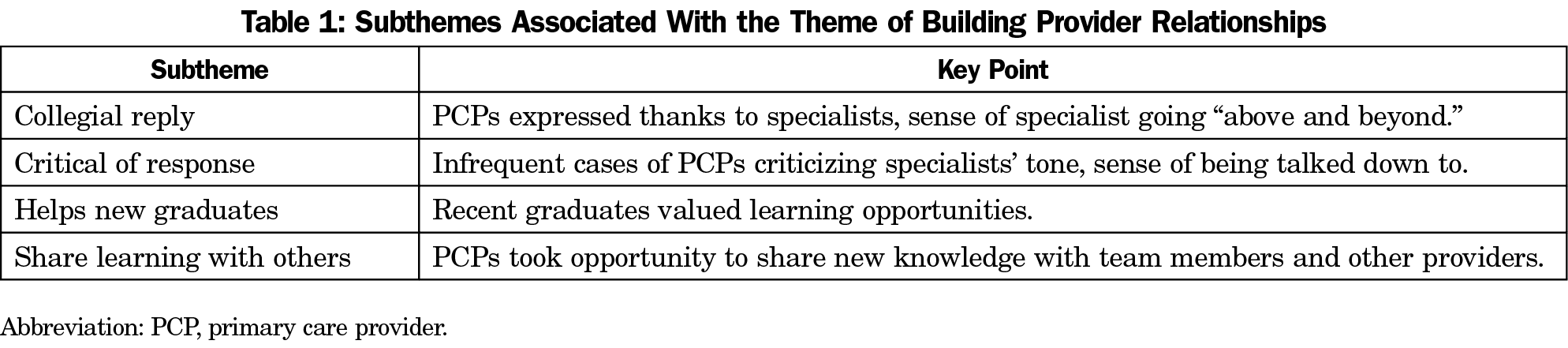

When discussing the educational and collegial value of eConsult cases, PCPs frequently reference the service’s ability to build stronger relationships between primary and specialist providers. We identified four subthemes: collegial reply, critical of response, helps new graduatess, and share learning with others (Table 1).

In many cases, PCPs expressed thanks to the specialist for the quick turnaround time and quality of responses they provided. PCPs appreciated the effort specialists put into their replies, which they noted in several cases went above and beyond what was necessary to answer the question. PCPs articulated a sense of providers helping one another, which supported a collegial exchange. For example, one PCP wrote

your feedback was great. Thanks for taking the time to add more info than required of you. Great learning tool for a new grad like myself!

While the majority of cases in our sample were positive, a few PCPs criticized the tone specialists took in their responses. In one instance, the PCP stated that the response “made me feel like I was being stupid/thick.” These occurrences were uncommon and highlight the importance of collegiality in eConsult exchanges.

A few PCPs identified themselves as recent graduates end emphasized the service’s value for them specifically. These PCPs found the educational opportunities that eConsult presents to be invaluable in the early years of their practice, with one PCP noting that the specialist’s response provided “excellent, timely feedback with additional teaching which will help me going forward in my career.”

In a few cases, PCPs expressed their intention to share what they learned among colleagues. For instance, one PCP discussed how they shared the case at an informal group session when they commented

Thanks for this interesting information… I happened to have my PBSG (problem based small group) at my house…and we looked at the information together.

Teaching Incorporated Into Answer

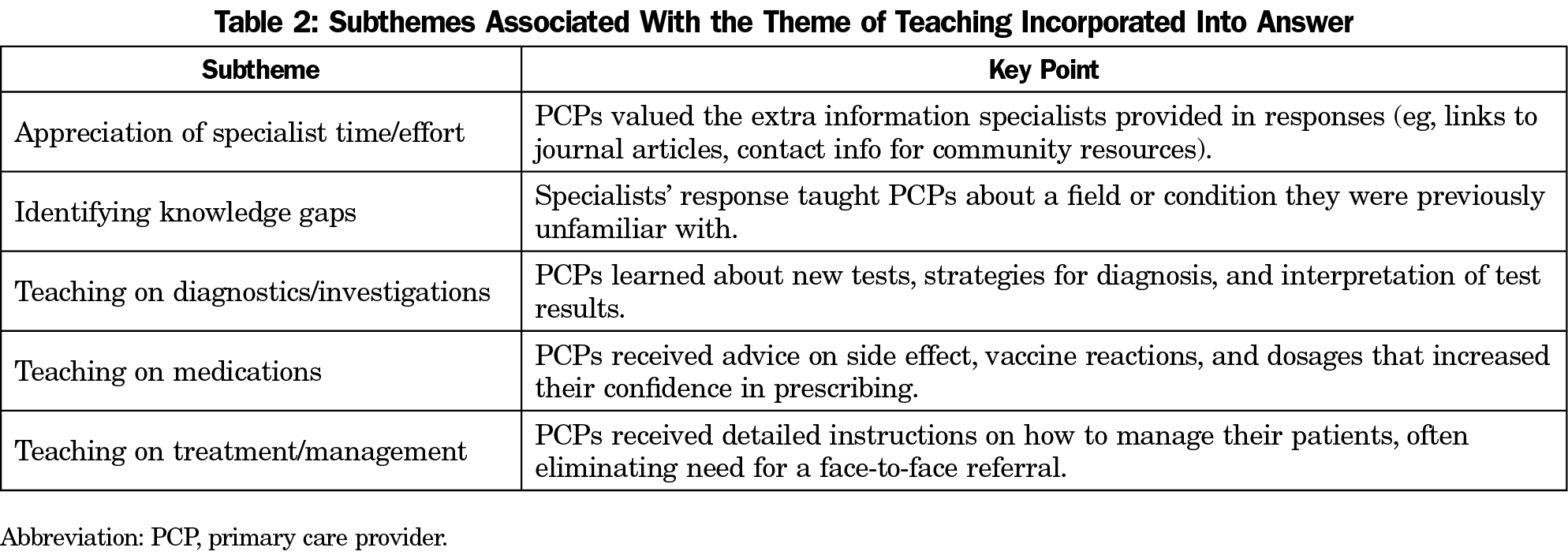

PCPs frequently noted that educational content was incorporated directly into the specialist’s response; that is, the very nature of posing a question about a patient to a specialist and receiving a reply is inherently educational. Five subthemes emerged under this theme: appreciation of specialist time/effort, identifying knowledge gaps, teaching on diagnostics/investigations, teaching on medications, and teaching on treatment/management (Table 2).

The first subtheme—appreciation of time and effort specialists put into their responses—was apparent as PCPs described the extra information or resources that specialists provided alongside their answer, which made it a more educational experience. Specific items included attaching a journal article that explored the question topic, advising them on helpful resources in their community, and simply providing more detail than was expected. The prevailing attitude among these PCPs is neatly summarized by one reply: “an excellent response with clear advice, some much appreciated teaching pearls, and information regarding current available hospital resources. […] your consults really should be used as a benchmark for what e-consults should look like.”

Another commonly cited benefit of eConsult was its ability to identify gaps in PCPs’ knowledge. Many PCPs described how the specialist’s response had made them aware of a field or condition they were previously unfamiliar with. This knowledge allowed them to seek further learning to address the deficiency. For instance, one PCP noted that they had sent a number of eConsult cases to hematology, which prompted them to seek further continuing medical education in that area.

PCPs described receiving education most frequently in diagnostics and investigations. PCPs mentioned learning about new tests they were previously unfamiliar with, strategies for diagnosis, and interpretation of test results. Furthermore, several PCPs noted that “it was valuable to hear the consultant’s thoughts and deliberations behind the clinical recommendations,” as it allowed them to better understand the underlying process that goes into a diagnosis.

Several PCPs cited learning more about various medications through eConsult. These PCPs received advice on side effect, vaccine reactions, and dosages that increased their confidence in prescribing.

The other area where PCPs frequently reported teaching was on treatment and management of patients. PCPs reported receiving detailed instructions on how to manage their patients, which often eliminated the need for a face-to-face referral. This provided relief to patients, especially for those who PCPs reported would find it difficult to attend an in-person appointment. For instance, one PCP stated that eConsult “helped give new ideas for a patient who cannot be transported for consult.”

Prompted Further Learning

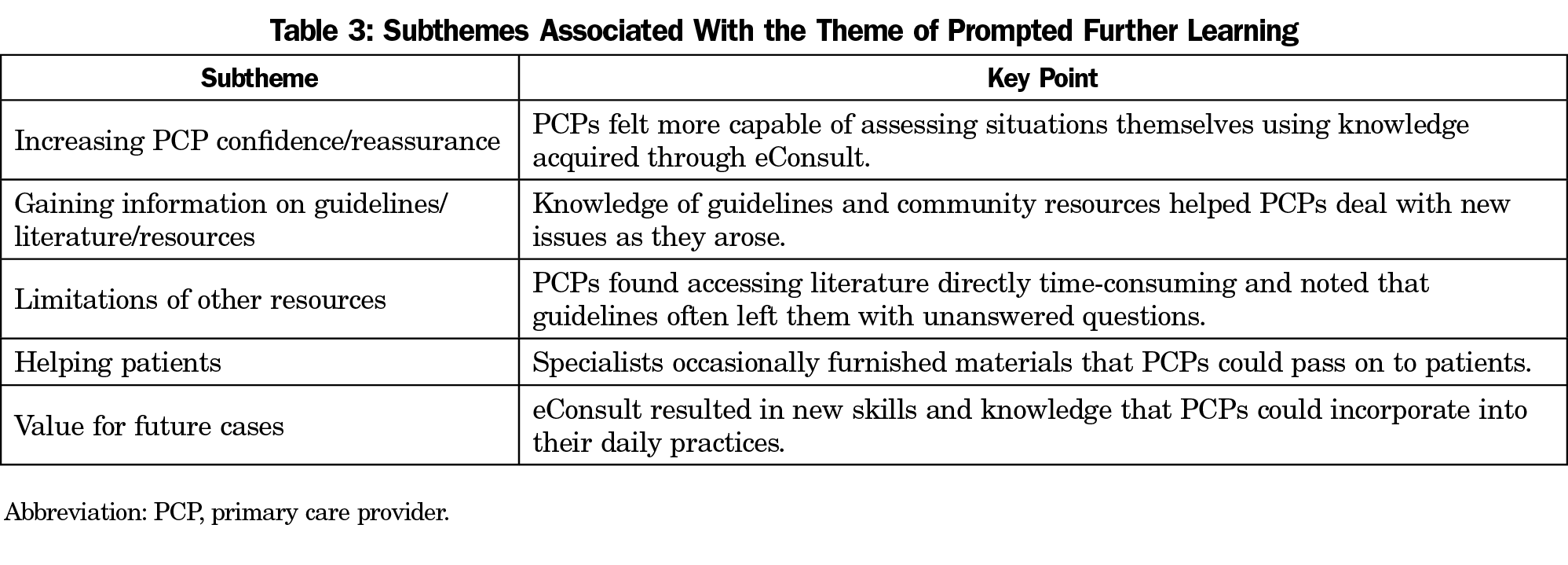

While PCPs regularly described the value of individual eConsult cases, they also made frequent reference to the ongoing benefits their learning had on themselves and their patients. Five subthemes emerged from this theme: increasing PCP confidence/reassurance, gaining information on guidelines/literature/resources, limitations of other resources, helping patients, and value for future cases (Table 3).

Several PCPs stated that the education they received through eConsult increased their confidence in their ability to provide care for the patient. These PCPs felt reassured and more capable of assessing the situation given the knowledge they’d acquired. As one PCP described:

I was very nervous about starting [name of medication], and was pleased to hear it was the right decision. I also learned that there are a few additional blood tests I need to do.

Often, specialists supplemented their responses by attaching articles, referencing guidelines, or discussing resources the PCPs could use in their patient’s care. PCPs valued this additional information, especially when treating patients with complex conditions. By providing guidelines, specialists helped PCPs deal with various contingencies, while their knowledge of community resources ensured that PCPs could refer their patients to effective sources of care. PCPs also appreciated receiving literature related to the case; as described by one PCP:

I really appreciate [the specialist] not only answered my question, but attached a journal article related to the topic to enhance my knowledge!

In several cases, PCPs emphasized the value of eConsult by citing the limitations of other knowledge sources. They discussed how looking up advice in academic literature can be time consuming, while guidelines alone often don’t account for the variations between cases and can leave PCPs with unanswered questions. PCPs valued how eConsult offered advice tailored to their specific case in a short time frame.

Occasionally, PCPs reported that specialists provided them with literature or other information they could give to patients. According to PCPs, patients appreciated this information, as it offered them a better understanding of their case and provided advice for ongoing treatment.

In many cases, PCPs stated that the information they received from the specialist would benefit future patients as well. PCPs valued the learning that comes with responses to individual cases, as it provided them with new skills, resources, and knowledge that they can incorporate into their daily practice. As one PCP said:

eConsult is great. The best part about it is I can often apply what I’ve learned in an eConsult to future patients as well. Not only have I avoided a referral with this eConsult but I’ll likely save time for future patients in similar situations.

Our study found that PCPs valued eConsult as an educational tool and a means to improve interprovider collegiality. Three themes emerged from the data: building provider relationships, teaching incorporated into answer, and prompting further learning. The eConsult service not only directly aided PCPs in their decision making for their patient, but also served as a communication channel that encouraged teaching and fostered stronger relationships between providers. These virtual connections and networks lead to unique opportunities for teaching and learning, all without providers ever meeting one another face to face. It is evident that a well-structured question or presentation of a clinical case by a PCP can lead to an informative clinical response by a specialist that is rich in information, advice, and support. Often an effective specialist response leads to immediate learning and application for the PCP.

The findings from our qualitative analysis are supported by additional data. On October 1, 2016, our team modified the closeout survey that PCPs complete after each case, replacing two questions about the service’s overall value with items pertaining specifically to its educational benefits. The first question asked PCPs to rank the specialist’s response on its educational value, using a 5-point Likert scale (with one being minimal value and five being excellent value). The second question asked users to determine whether “this eConsult addresses an important clinical problem that should be incorporated into upcoming CME (continuing medical education) events.” In a study analyzing eConsult’s impact using numerous metrics, we examined responses to these questions from 10,364 cases, and found that PCPs ranked eConsult as having high or very high educational value in 92% of cases.26 PCPs were likewise supportive of incorporating eConsult answers into CME events, with 57% agreeing and only 8% disagreeing.26 Such responses lend credence to our conclusions, as they demonstrate an appetite for eConsult as an educational tool across a significant wealth of data. Furthermore, other electronic communication platforms have shown similar findings. For example, the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center developed a telementoring program for health professionals to improve pain management expertise. Clinicians practicing in rural and underserved communities convened weekly by telehealth technology (Project ECHO Pain). An evaluation of this program found that users demonstrated greater professional competence and improved practice by applying what they learned during case presentations.27 Likewise, the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services conducted a qualitative analysis of 40 interviews with PCPs using their eConsult system, who reported that the service’s clinical and educational value was a key benefit.28

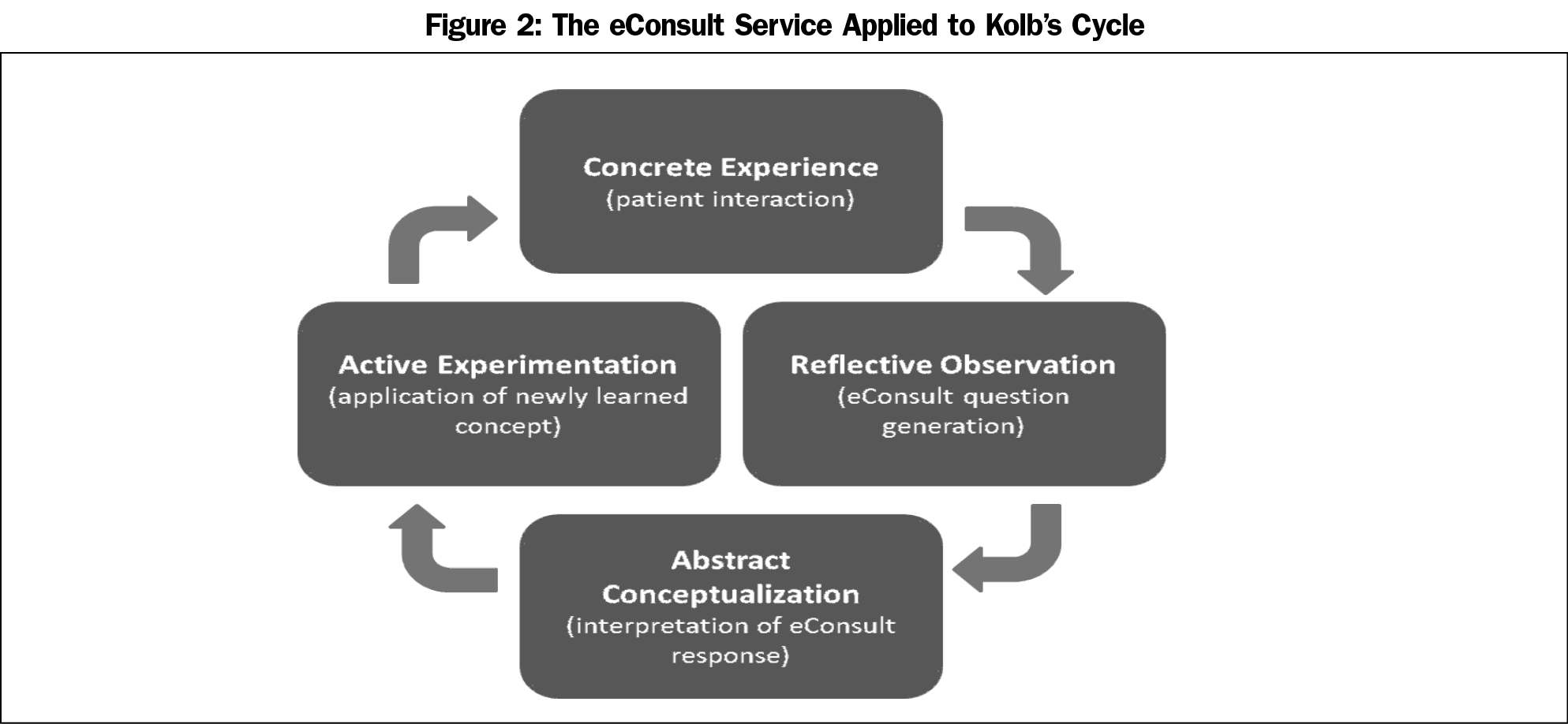

The three themes derived from our content analysis correspond to the four-level framework for experiential learning made possible through eConsult.16 Experiential learning is based on the notion that knowledge is created through transformation of experience. David Kolb described this process in a continuous cycle (Kolb’s cycle) with four phases: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation.29 When applied to the eConsult exchange, the inner core of the framework stresses the importance of practice-based learning and reflective practice (Figure 2). Receiving clinical advice or confirming a course of action from a specialist is of great value to a PCP. Often a practitioner wants an expert opinion on a given treatment or management plan. Through eConsult, specialists provide PCPs with new knowledge or resources, allowing them to reflect on how they treated a given patient. Each PCP repeats the learning cycle when seeing a patient with a similar presentation and applies their new knowledge gained from the eConsult.

A second condition of the eConsult framework is the building of rapport and relationships amongst providers. eConsult is a good example of a collaborative partnership model to provide quality care to patients, as it naturally builds trust into the network. The theory of connectivism states that a network is a connection of at least two nodes, linked to share resources. Using eConsult as an example, any given PCP will be connected to a number of specialists, creating multiple nodes and forming part of a network. The specialist in turn will be part of numerous nodes, connected by many PCPs. The premise of connectivism is that knowledge is distributed across the network. Information is continually changing over time as people’s understanding of a subject or problem evolves. The ability to make decisions based on changing understandings is integral to the learning process and is an important concept of connectivism.30 As PCPs continue to ask the same specialist for trusted advice, over time a strong relationship develops which reduces the fragmentation of care, ultimately improving the quality of service to patients. Collegiality is also an important element of building rapport and relationships among providers. Specialists who reply to questions with “if this were my patient…” or “good question, I would do …” exemplify respect. In turn, appreciation by PCPs for favorable advice received from specialists goes a long way toward building rapport.

Moreover the themes demonstrate how eConsult acts as a bridge connecting formal and informal learning settings. It is the learning that arises from formal learning (teaching from the specialist response) to prompting self-learning (further learning and additional resources through formal and informal settings in particular, such CPD courses and hallway conversations,). All three forms are important for lifelong learning.31 However, despite these benefits, further work is needed to support broader adoption of eConsult services as vehicles of learning and as means of improving patients’ access to care. While such services have grown in recent years, there remain a large number of providers in many countries who have not adopted these innovations. A recent study by Kane and Gillis notes that only 11.2% of US physicians use online-based communication tools to interact with other health providers.32

This study had several limitations. The analysis was done on a set of free-text open-ended survey questions, and there is some literature documenting potential issues of achieving enough data richness from using only free-text responses.33 Furthermore, our inclusion criteria resulted in a data set comprised of only a small percentage (6%) of total comments, which risks overstating the breadth of consensus among PCPs and limits the generalizability of our findings. However, we attempted to minimize these issues by avoiding a purely numerical/counting analysis and instead conducting a rigorous thematic analysis with several rounds of coding, discussion, and consolidation among a team with differing professional experiences in order to extract meaningful conclusions. Also, although the data was free-text, many of the comments were rich in context, emotion, and educational experience as evidenced by lengthy responses outlining PCPs connection to the specialist and appreciation, and sometimes negative emotions as well. Finally, we also linked our analysis with a clearly established framework and existing literature to enrich our themes and conclusions. Other limitations include a small sample size and potential overrepresentation of users who appreciated the service as they may have been more likely to leave comments.

The Champlain BASE eConsult service has educational value for providers. PCPs described the service’s ability to foster stronger relationships with specialists, deliver responses that provided teaching in multiple areas of their practice, and support further learning that extended beyond the case at hand and into their overall practice. Further study is underway to explore how questions and replies submitted through eConsult can be used to facilitate reflective learning and promote feedback to providers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the health care providers who use the eConsult service.

Funding: Financial support for the Champlain BASE eConsult service was received from eHealth Ontario, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, and the Champlain LHIN. Grant support was received from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

References

- Cook NL, Hicks LS, O’Malley AJ, Keegan T, Guadagnoli E, Landon BE. Access to specialty care and medical services in community health centers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(5):1459-1468. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1459

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. How Canada Compares: Results From The Commonwealth Fund's 2016 International Health Policy Survey of Adults in 11 Countries. https://www cihi ca/sites/default/files/document/text-alternative-version-2016-cmwf-en-web.pdf. Accessed April 3, 2019.

- Cummings JR, Allen L, Clennon J, Ji X, Druss BG. Geographic access to specialty mental health care across high-and low-income US communities. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):476-484. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0303

- Canadian Intitute for Health Information. Health Care in Canada, 2012: A Focus on Wait Times. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2012.

- Barua B, Esmail N. Waiting Your Turn: Wait Times for Health Care in Canada. Vancouver: Fraser Institute; 2013.

- Chen AH, Yee HF Jr. Improving the primary care-specialty care interface: getting from here to there. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(11):1024-1026. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.140

- Barua B, Esmail N, Jackson T. The Effect of Wait Times on Mortality in Canada. Vancouver: Fraser Institute; 2014.

- Liddy C, Drosinis P, Keely E. Electronic consultation systems: worldwide prevalence and their impact on patient care-a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2016;33(3):274-285. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmw024

- Vimalananda VG, Gupte G, Seraj SM, et al. Electronic consultations (e-consults) to improve access to specialty care: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. J Telemed Telecare. 2015;21(6):323-330. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X15582108

- Rodriguez KL, Burkitt KH, Bayliss NK, et al. Veteran, primary care provider, and specialist satisfaction with electronic consultation. JMIR Med Inform. 2015;3(1):e5. https://doi.org/10.2196/medinform.3725

- Liddy C, Afkham A, Drosinis P, Joschko J, Keely E. Impact and satisfaction with a new eConsult service: a mixed methods study of primary care providers. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(3):394-403. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2015.03.140255

- Olayiwola JN, Anderson D, Jepeal N, et al. Electronic consultations to improve the primary care-specialty care interface for cardiology in the medically underserved: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(2):133-140. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1869

- Liddy C, Deri Armstrong C, Drosinis P, Mito-Yobo F, Afkham A, Keely E. What are the costs of improving access to specialists through eConsultation? The Champlain BASE experience. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;209:67-74.

- Liddy C, Drosinis P, Deri Armstrong C, McKellips F, Afkham A, Keely E. What are the cost savings associated with providing access to specialist care through the Champlain BASE eConsult service? A costing evaluation. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e010920. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010920

- Kwok J, Olayiwola JN, Knox M, Murphy EJ, Tuot DS. Electronic consultation system demonstrates educational benefit for primary care providers. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;1357633X17711822.

- Keely EJ, Archibald D, Tuot DS, Lochnan H, Liddy C. Unique educational opportunities arising from electronic consultation services. Acad Med. 2017;92(1):45-51. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001472

- Archibald D, Liddy C, Lochnan HA, Hendry PJ, Keely EJ. Using clinical questions asked by primary care providers through eConsults to inform continuing professional development. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2018;38(1):41-48. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000187 PMID:29351133

- Lave J. Cognition in Practice: Mind, Mathematics and Culture in Everyday Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1988. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511609268

- Brown JS, Collins A, Duguid P. Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educ Res. 1989;18(1):32-42. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X018001032

- Lave J, Wenger E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815355

- Siemens G. Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. Int J Instruct Technol Distance Learning. 2005;2(1):3-10.

- Liddy C, Rowan MS, Afkham A, Maranger J, Keely E. Building access to specialist care through e-consultation. Open Med. 2013;7(1):e1-e8.

- Liddy C, Moroz I, Afkham A, Keely E. Sustainability of a primary care driven eConsult service. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(2):120-126. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2177

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Research. London: SagePublications Ltd; 2006.

- Liddy C, Keely E. Using the quadruple aim framework to measure impact of heath technology implementation: A case study of eConsult. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(3):445-455. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2018.03.170397

- Katzman JG, Comerci G Jr, Boyle JF, et al. Innovative telementoring for pain management: project ECHO pain. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2014;34(1):68-75. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.21210

- Lee MS, Ray KN, Mehrotra A, Giboney P, Yee HF Jr, Barnett ML. Primary care practitioners perceptions of electronic consult systems: a qualitative analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):782-789. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0738

- Kolb DA. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Upper Saddle River, NJ: FT Press; 2014.

- 30. Kop R, Hill A. Connectivism: learning theory of the future or vestige of the past? Int Rev Res Open Distributed Learning. 2008;9(3).

- Merriam SB, Caffarella RS, Baumgartner LM. Learning in Adulthood: A Comprehensive Guide. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2012.

- Kane CK, Gillis K. The Use Of Telemedicine By Physicians: Still The Exception Rather Than The Rule. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(12):1923-1930. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05077

- LaDonna KA, Taylor T, Lingard L. Why Open-Ended Survey Questions Are Unlikely to Support Rigorous Qualitative Insights. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):347-349. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002088

There are no comments for this article.