Family medicine has made integration of behavioral health and primary care an essential component of residency education.1 While most of the effort has focused on ambulatory care, integrating behavioral sciences into inpatient curricula has lagged.2,3 Inpatient training provides an important context to examine issues of professional development, because of the severity of coexisting medical and psychosocial problems, the intensity of short hospital stays, and the pressured environment for residents whose work is closely observed. In addition, residents continually form intense, transient relationships with patients, families, and health care professionals while making high-stake, time-sensitive decisions. Rarely do they have the time or guidance to consider how the inpatient experience and these relationships affect their clinical care and professional development. To address this need, we developed inpatient rounds to discuss difficult clinical and professional development issues.

BRIEF REPORTS

Behavioral Science Rounds: Identifying and Addressing the Challenging Issues That Residents Face on a Family Medicine Inpatient Service

George W. Saba, PhD | Teresa Villela, MD | Ronald H. Goldschmidt, MD

Fam Med. 2019;51(7):603-608.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2019.726006

Background and Objectives: Training residents in the care of hospitalized patients offers an opportunity to integrate behavioral science education with medical care and to foster professional growth, given the severity of coexisting medical and psychosocial problems and the formation of intense transient relationships. Rarely do residents have the time or guidance to reflect on how these experiences and relationships affect them. Weekly behavioral science rounds (BSR) provide dedicated time to reflect on and discuss challenging clinical and professional developmental issues arising during inpatient training.

Methods: To understand the range of issues that learners experience, we analyzed facilitator notes of 45 consecutive BSR discussions. Through open coding analysis we identified the common topics and recurring themes raised by residents.

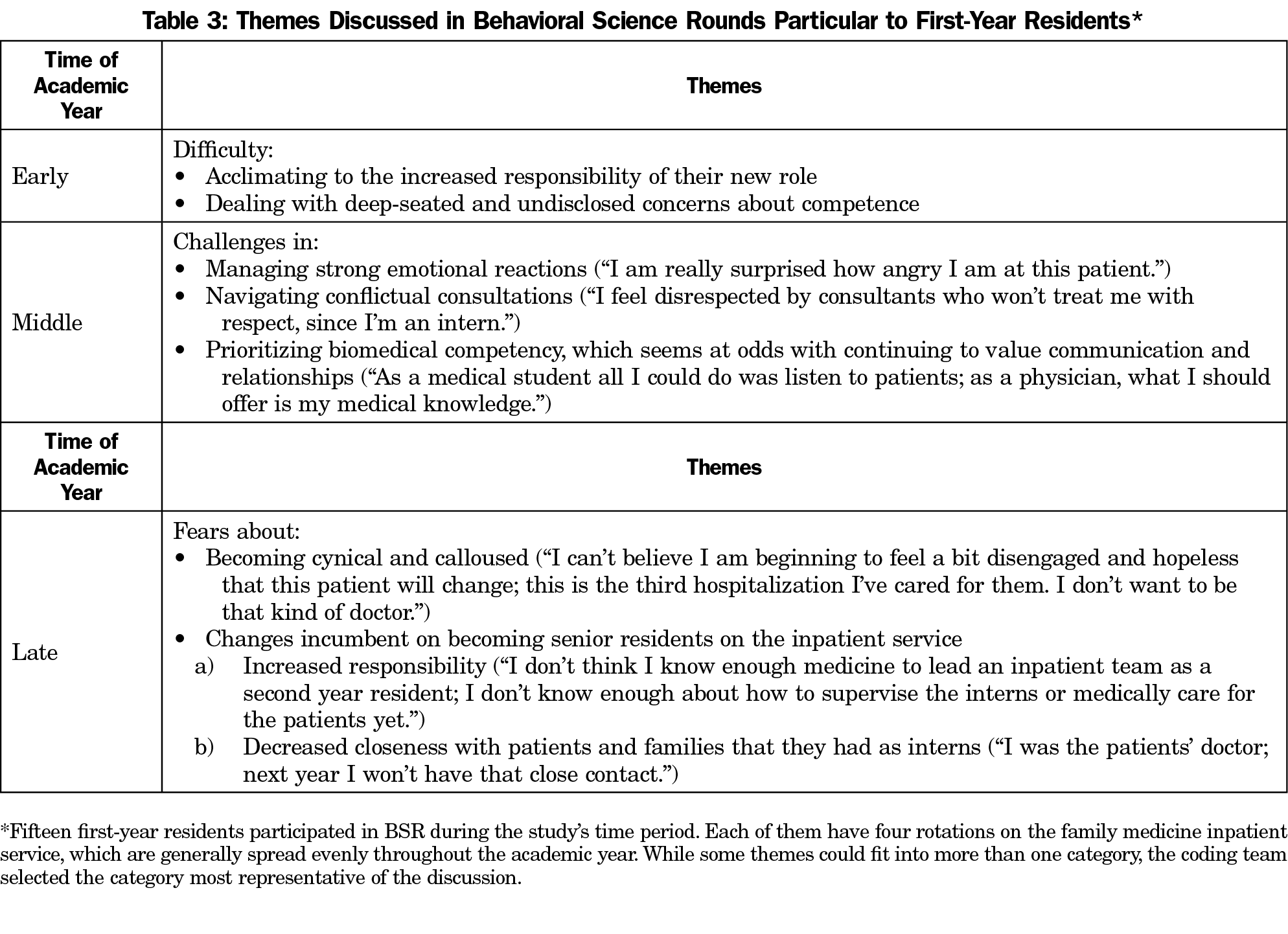

Results: The most common topics related to residents’ emotional responses, clinical challenges, and interpersonal conflicts. We identified frequently recurring themes, including understanding the power and limitations of the physician, defining roles and responsibilities, and articulating personal beliefs and values. Early first-year residents had difficulty acclimating to increased responsibility and worried about competence; later, they experienced strong emotional reactions, feared becoming cynical, and were apprehensive about future leadership roles.

Conclusions: Inpatient BSR can serve as an important educational intervention and professional development tool at a critical time in training. BSR requires a commitment of teaching resources, an assurance that they will occur regularly, and a culture of safety in which residents trust their discussions will be confidential and that they will be treated with respect and caring.

Context and Rationale

In 1979, the University of California, San Francisco Family and Community Medicine Residency established the Family Medicine Inpatient Service (FMIS) at San Francisco General Hospital, a publicly-funded safety net hospital. Most patients hospitalized on FMIS are from multiracial/ethnic, underserved communities that face psychosocial stressors (poverty, racism, unstable housing, substance use). The FMIS curriculum applies a family systems approach to the care of seriously ill adults.4 In 1983, we created behavioral science rounds (BSR) to address residents’ clinical and educational inpatient experience, allowing them time to reflect and explore their reactions and adaptations to challenging interactions and develop relationship-oriented strategies for their clinical care and growth. Since 1983, more than 450 individual family medicine residents have participated in BSR during each year of residency.

Structure and Format

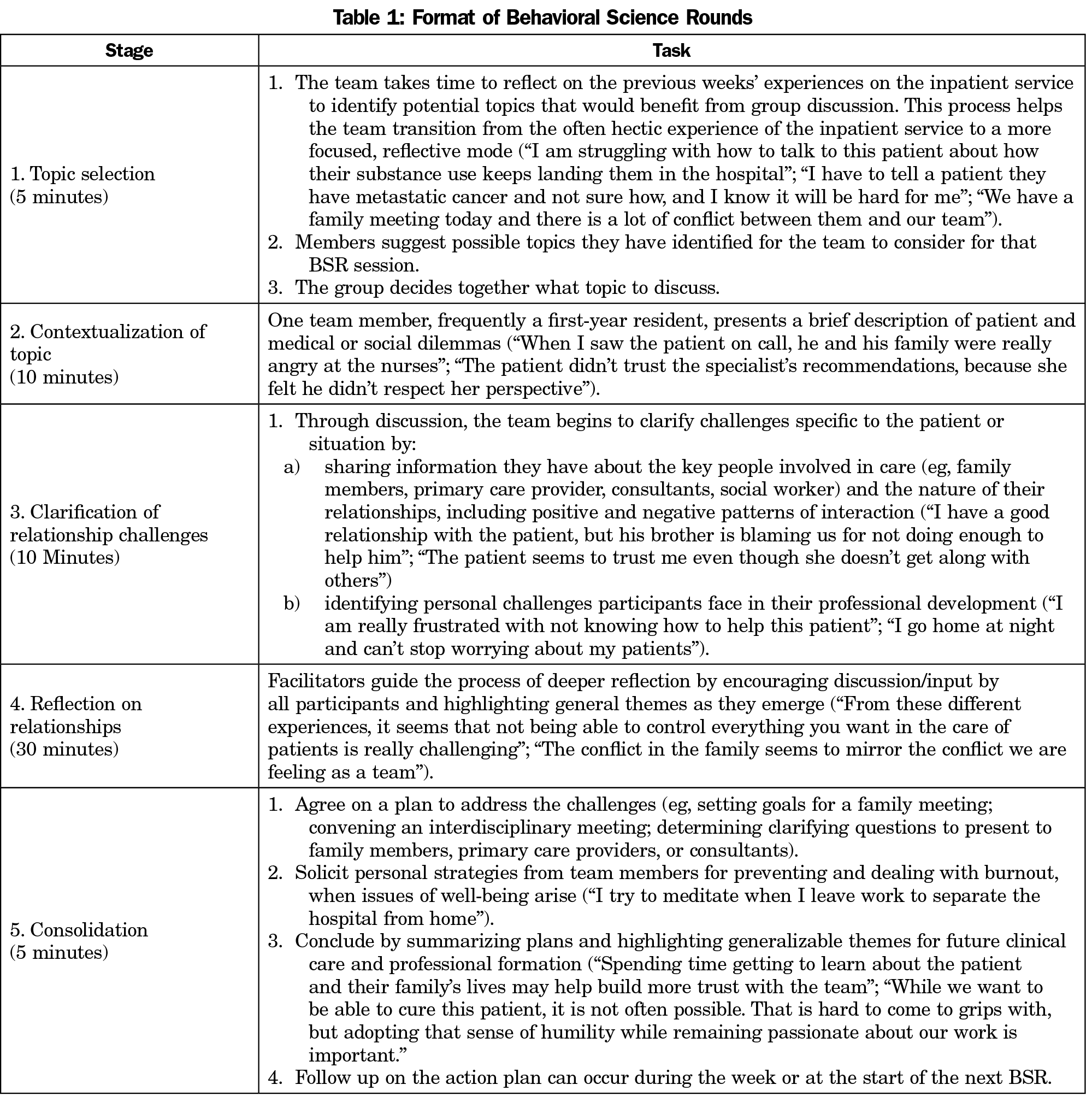

BSR sessions occur weekly for 1 hour and include the inpatient team of eight family medicine residents, up to two medical students, a fourth-year chief resident, and two facilitators—the family physician inpatient attending and a behavioral scientist faculty member (Table 1). Each resident participates in 32 hours of BSR over 3 years.

BSR begins with team members reflecting on recent inpatient experiences and suggesting potential topics, generally prompted by patient care experiences. The group determines the topic, a team member presents the basic issues, and others add information about key relationships. Invariably the discussion evolves into deeper reflection. Participants share their conflicts with patients, families, and colleagues, their emotional reactions, and how the experience impacts their development as physicians. BSR faculty members avoid putting residents on the spot, in order to create a safe context for shared learning. Senior residents and faculty members frequently offer lessons learned from similar situations. BSR concludes with the group developing a plan to address relationship issues and sharing strategies for professional formation. Although BSR shares some similarities with Balint Groups (confidentiality, focus on patient-physician relationship), it changes group composition frequently, occurs weekly, explores relationships beyond the patient, actively involves the participant raising the issue, and concludes with an action plan.5

To identify common topics and themes from BSR discussions, the authors used open coding6 to analyze the behavioral science facilitator’s (G.S.) notes written during a sample of 45 consecutive weekly BSR sessions in one academic year 2016-2017. The structure and note-taking process has remained the same since 1983 and did not change during this study. The notes serve to aid facilitation by tracking issues raised; they are not reviewed by facilitators or residents for representativeness. This review retrospectively examined extant notes from the 45 sessions. T.V. and R.H.G. were family medicine faculty attendings who cofacilitated 10 and nine sessions, respectively. Each BSR included two PGY-3 residents, two PGY-2 residents and four PGY-1 residents. Forty-five different residents participated over the time period. Each PGY-3 and PGY-2 resident would have attended eight sessions and each PGY-1 resident would have attended 16 sessions.

All authors independently reviewed the notes to identify initial descriptive codes and rereviewed each note using a constant comparative method to conduct multistaged coding. Open coding of the raw data helped develop categories, axial coding organized these into patterns, and selective coding developed theoretical formulations to link key variables to themes. Authors resolved analytic discrepancies. The University of California Institutional Review Board Human Subjects Committee determined review was not required.

The review of the BSR discussions identified topics frequently raised by residents:

- Coping with emotional responses to the care of hospitalized patients

- Reviewing new/difficult diagnoses with patients and/or families

- Treating challenging clinical conditions (eg, chronic pain, substance use disorders)

- Assessing decision-making capacity

- Addressing management disagreements within the team, family, consultants, and/or primary care clinician

- Managing issues of mistrust and misunderstanding

- Identifying/addressing institutional discrimination and implicit bias in care

- Preparing ourselves, patients, and families for death.

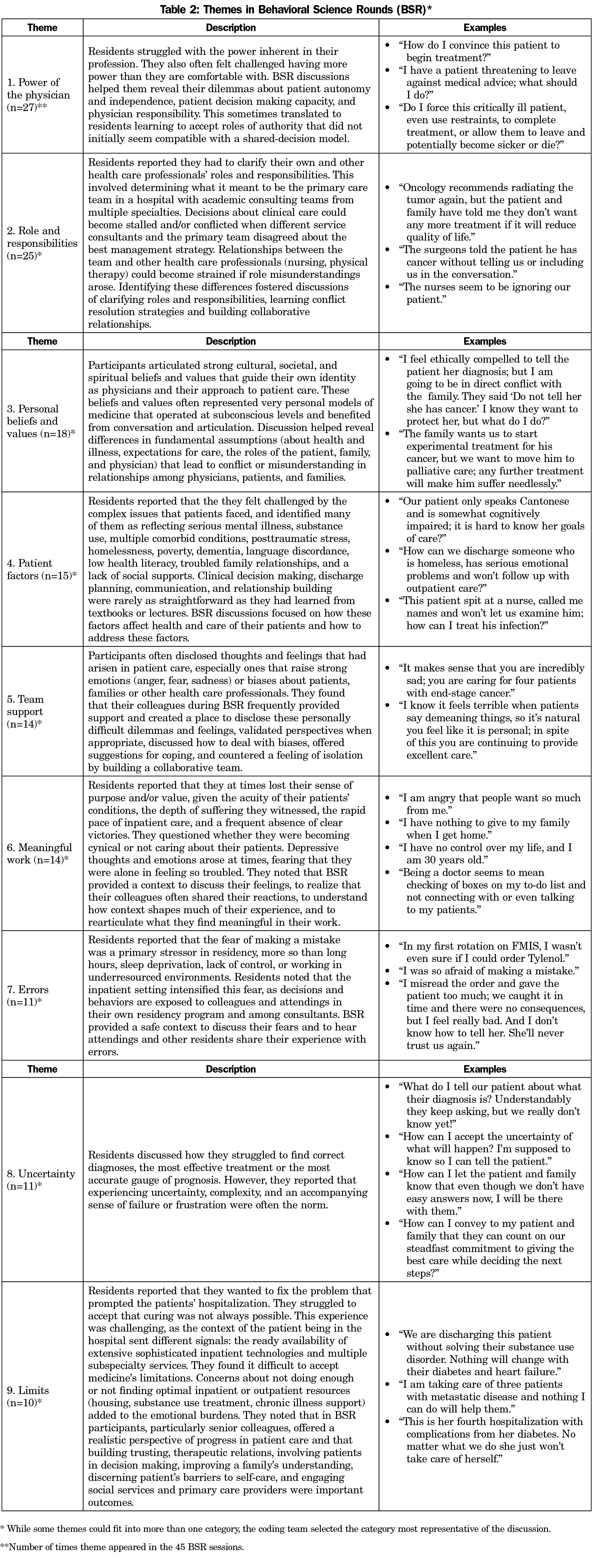

Discussions generally moved to deeper issues that residents commonly struggled with (Table 2). Recurrent themes particular to first-year residents were also identified (Table 3).

Value to Resident Experience

Residents consistently comment in anonymous evaluations on BSR’s value as “a space to share and explore very challenging topics,” “a space to discuss concerns and fears,” “reserved time each week to reflect and discuss an important issue with my colleagues,” and “a step-back moment during the busiest months.” Residents also view BSR as important for well-being. Given the risk of depression and suicide among physicians,7,8 BSR offers a context to share emotional reactions, gain support from colleagues, and learn coping strategies.

The most common topics raised in BSR were related to residents’ clinical challenges, difficult emotional responses, and interpersonal conflicts. Discussions revealed deeper issues they struggled with, including understanding the power and limitations of the physician, defining roles and responsibilities, and articulating personal beliefs and values. Early first-year residents had difficulty acclimating to increased responsibility and worried about competence; later, they experienced strong emotional reactions, feared becoming cynical, and were apprehensive about future leadership roles. Limitations include the retrospective review of extant notes that were taken by one coauthor/coder who facilitated all sessions and were not reviewed by faculty or residents.

Weekly dedicated inpatient behavioral science rounds can serve as an important educational intervention and professional development tool at a critical and vulnerable time in physician training.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the many residents, faculty, patients, and families who have supported and participated in this curriculum.

References

- Saultz J. Integrating behavioral health and primary care. Fam Med. 2015;47(7):509-510.

- Kertesz JW, Delbridge EJ, Felix DS. Models for integrating behavioral medicine on a family medicine in-patient teaching service. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2014;47(4):357-367. https://doi.org/10.2190/PM.47.4.j

- Satterfield JM, Bereknyei S, Hilton JF, et al. The prevalence of social and behavioral topics and related educational opportunities during attending rounds. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1548-1557. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000483

- Sluzki CE. On training to “think interactionally”. Soc Sci Med. 1974;8(9-10):483-485. https://doi.org/10.1016/0037-7856(74)90070-5

- American Balint Society. Balint groups in residency training. 2017. http://www.americanbalintsociety.org/content.aspx?page_id=22&club_id=445043&module. Accessed December 22, 2017.

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008.

- Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2373-2383. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.15845

- Schwenk TL. Resident depression: the tip of a graduate medical education. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2357-2358. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.15408

Lead Author

George W. Saba, PhD

Affiliations: Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine

Co-Authors

Teresa Villela, MD - Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine

Ronald H. Goldschmidt, MD - Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine

Corresponding Author

George W. Saba, PhD

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.