The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Common Residency Program Requirements stipulate that each faculty member’s performance must be evaluated annually, and must include “a review of the faculty member’s clinical teaching abilities.”1 Feedback is an essential element in this process. Yet, the culture of medicine poses challenges to developing effective feedback systems: valid bidirectional feedback can be challenging in a hierarchical educational structure; patient care takes priority over teaching; and learners often have limited contact with multiple instructors.2 Likewise, no uniform expectations are universally accepted for clinical instruction,3-5 despite existing for learners.6,7 Without well-defined expectations regarding instruction, feedback provided to faculty members may not be adequately focused. This paper explores current and ideal characteristics of faculty teaching evaluation systems from the perspectives of faculty, residents, and residency program directors (PDs).

BRIEF REPORTS

Residency Faculty Teaching Evaluation: What Do Faculty, Residents, and Program Directors Want?

Linda Myerholtz, PhD | Alfred Reid, MA | Hannah M. Baker, MPH | Lisa Rollins, PhD | Cristen P. Page, MD, MPH

Fam Med. 2019;51(6):509-515.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2019.168353

Background and Objectives: The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Common Residency Program Requirements stipulate that each faculty member’s performance be evaluated annually. Feedback is essential to this process, yet the culture of medicine poses challenges to developing effective feedback systems. The current study explores existing and ideal characteristics of faculty teaching evaluation systems from the perspectives of key stakeholders: faculty, residents, and residency program directors (PDs).

Methods: We utilized two qualitative approaches: (1) confidential semistructured telephone interviews with PDs from a convenience sample of eight family medicine residency programs, (2) qualitative responses from an anonymous online survey of faculty and residents in the same eight programs. We used inductive thematic analysis to analyze the interviews and survey responses. Data collection occurred in the fall of 2017.

Results: All eight (100%) of the PDs completed interviews. Survey response rates for faculty and residents were 79% (99/126) and 70% (152/216), respectively. Both PD and faculty responses identified a desire for actionable, real-time, frequent feedback used to foster continued professional development. Themes unique to faculty included easy accessibility and feedback from peers. Residents expressed an interest in in-person feedback and a process minimizing potential retribution. Residents indicated that feedback should be based on shared understanding of what skill(s) the faculty member is trying to address.

Conclusions: PDs, faculty, and residents share a desire to provide faculty with meaningful, specific, and real-time feedback. Programs should strive to provide a culture in which feedback is an integral part of the learning process for both residents and faculty.

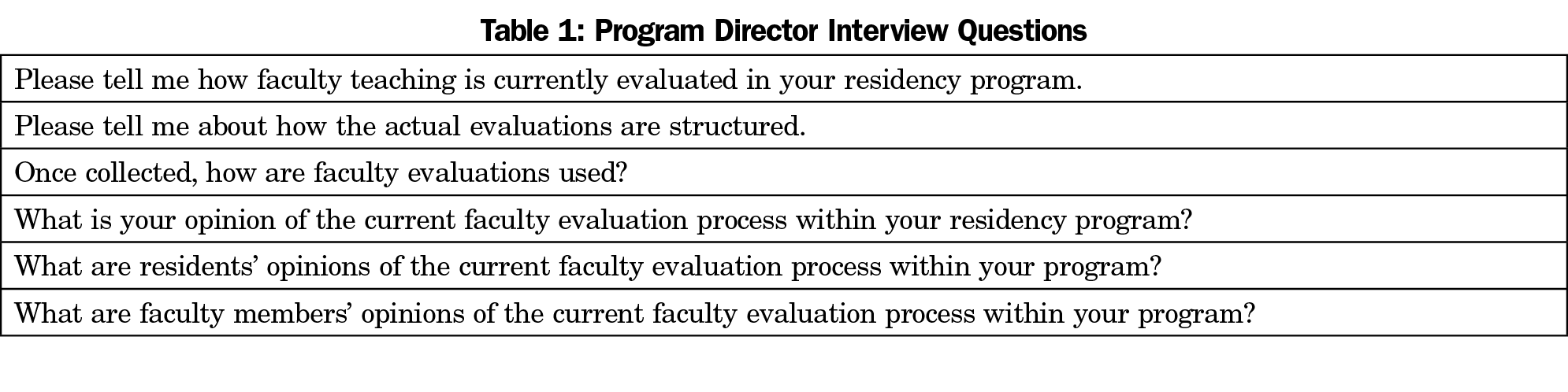

We utilized two qualitative approaches. First, we conducted confidential semistructured telephone interviews with PDs from a convenience sample of eight family medicine (FM) residency programs. The interview guide for the semistructured interviews (Table 1) was formulated after conducting a literature review and was developed by a panel of faculty experts in the fields of graduate medical education, behavioral science, and qualitative data collection. The expert panel also included a former residency program director. Questions explored the current process for faculty teaching evaluation with probes related to challenges, successes, barriers, and gaps within the current system. One member of the research team (H.B.) conducted the interviews. The interviewer asked each question of the program directors, along with appropriate probes in order to ensure a thorough exploration of each question. Interviews were recorded with permission of the respondents and transcribed verbatim.

Second, we emailed an anonymous online survey link to faculty and residents from the same eight programs with questions related to participants’ perceptions of the current faculty teaching evaluation system. The survey was primarily quantitative, but concluded with the open-ended question: “In your ideal world, what would the faculty teaching evaluation process look like?” A postimplementation survey was also administered to programs following piloting of a mobile application to collect point of teaching feedback from learners, and the quantitative data from pre- and postimplementation will be analyzed together and published separately.

The research team used an inductive thematic analysis approach8 to analyze the interview transcripts and narrative survey responses; one research team member reviewed the data and developed initial codes, sorting quotes and salient text by code. The other team members then reviewed the initial codes and related text and developed additional codes that emerged from the data. The team then met to resolve coding discrepancies and discuss emergent themes. It is important to note that rather than conducting data collection and analysis to the point of saturation, the research team analyzed the data with the intention of identifying and developing salient themes mentioned across programs. This is a result of the data collection being a part of a small implementation study of eight family medicine programs pilot-testing the aforementioned mobile application.

The University of North Carolina Chapel Hill’s Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB #17-2052).

Interviews

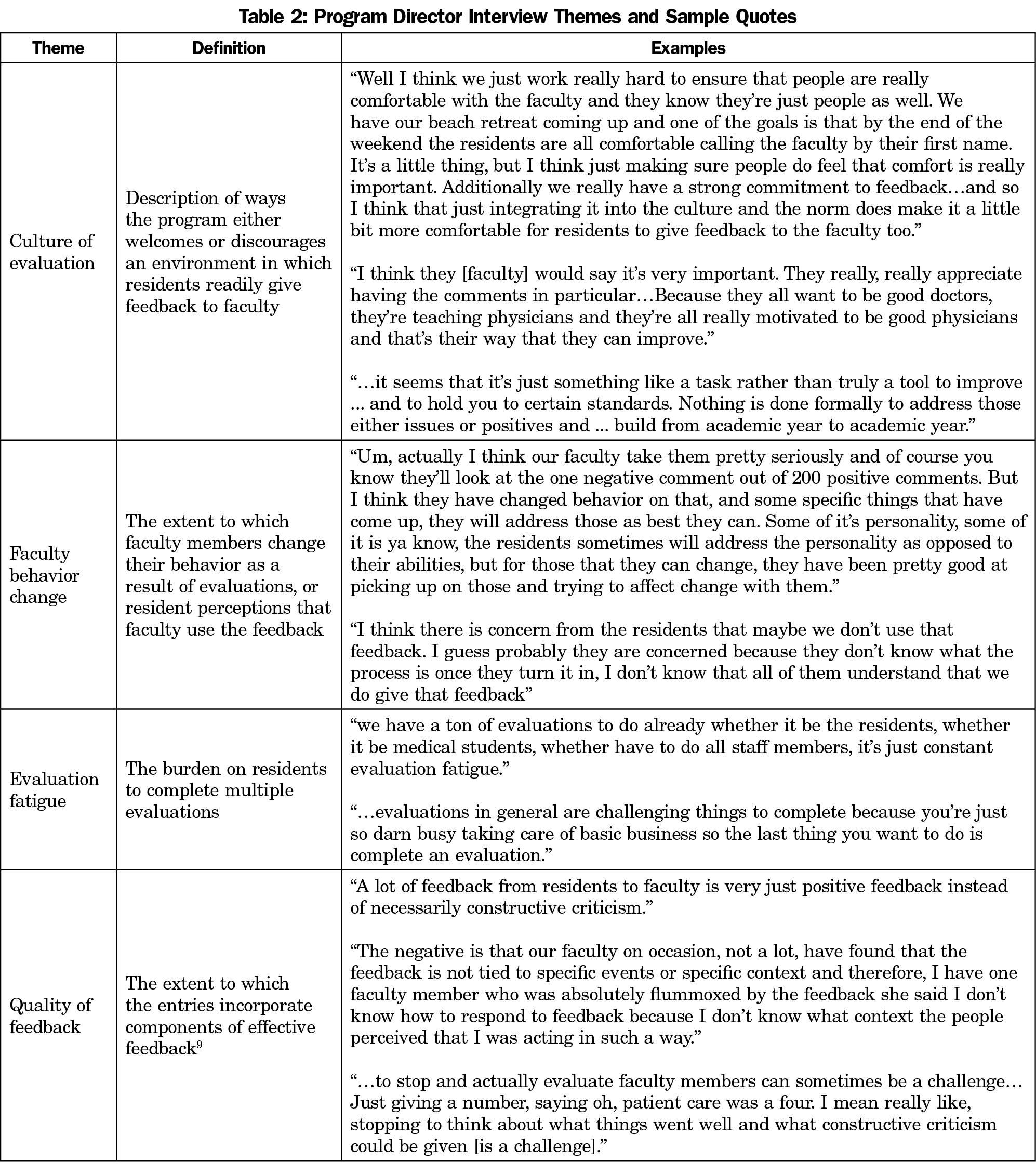

All eight (100%) PDs completed interviews. The following themes emerged across interviews.

Culture of Evaluation. PDs discussed programmatic conventions that foster a culture of evaluation, including having both residents and faculty involved in the feedback process, maintaining a high degree of mutual trust, and a shared understanding of feedback as an important element of performance improvement rather than just a task to be completed.

Faculty Behavior Change. The majority of PDs described the importance of an evaluation system that fosters faculty behavior change; several indicated they believed their programs succeeded in this regard.

Evaluation Fatigue. Many PDs identified the large number of evaluations residents are required to complete as a barrier; several also indicated they have attempted to address this barrier within their programs.

Quality of Feedback. Several of the PDs noted that the feedback to faculty members is often of low quality, provides no actionable information, and is often received out of context or too long after the event.

Table 2 provides illustrative quotes of each theme.

Surveys

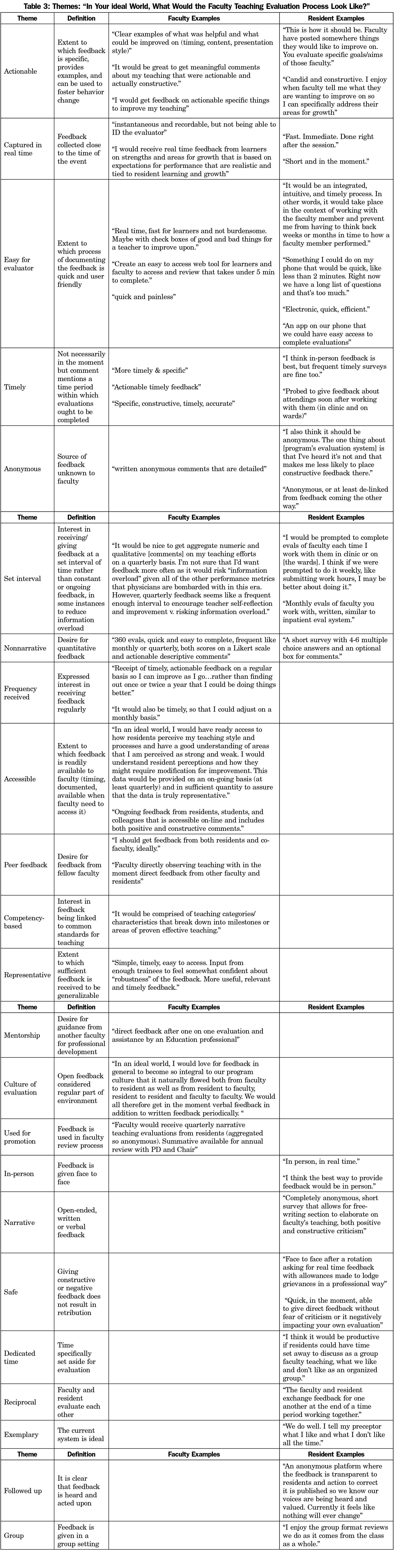

Survey response rates for faculty and residents were 79% (99/126) and 70% (152/216), respectively. Forty-nine percent (62/126) of faculty and 28% of residents (61/216) responded to the specific open-ended question described in this paper.

As shown in Table 3, faculty and residents expressed several themes in common regarding the ideal feedback system. Half of respondents in both groups noted that feedback should be specific enough to enable behavior change. As separate groups, similar proportions of faculty and residents described an evaluation process that captured feedback in real time. Roughly equal proportions of faculty and residents used the word “timely,” but without specifying what that meant. Similar proportions of faculty and residents indicated a desire for feedback at set time intervals rather than constant or ongoing. Faculty and residents differed in the extent to which they mentioned ease of use of the feedback mechanism, with faculty mentioning this less often than residents. This is also the case for ability for feedback to be provided anonymously, with residents mentioning this more often than faculty.

Eight themes were unique to faculty, with the following three being the most salient: regular frequency of feedback (29%), easy accessibility of feedback (21%), and feedback from peers (10%). Another eight themes were unique to residents, with the following three being the most salient: a preference for providing in-person feedback (21%), the opportunity to provide narrative feedback (15%), and a feedback process that does not result in retribution for negative feedback (13%). The rest of the themes are listed in Table 3.

Many of our findings are consistent with commonly accepted characteristics of effective feedback.9 Throughout the data collection process, we did not explicitly distinguish between feedback and evaluation, and results reflect this conceptual overlap among participants. Both PD and faculty responses identified a desire for actionable, real-time, frequent feedback that can be used to foster continued professional development. Residents indicated that feedback should be meaningful and with a level of specificity that helps faculty improve. Residents also indicated that faculty feedback should mirror the resident feedback process (ie, with explicit, shared understanding of what skill(s) the faculty member is trying to address).

These results highlight important process and contextual issues. All stakeholders indicated that feedback for faculty should not be burdensome. PDs emphasized the need for buy-in from both residents and faculty and for a culture that promotes multidirectional feedback as a part of continuous improvement. In addition, while the theme of anonymity was salient for residents, few faculty members mentioned this as important. Of particular note is the seemingly contradictory finding that residents preferred in-person feedback, yet they also expressed the need for anonymity. This reflects an important tension in the way residents perceive feedback, and while open, bidirectional feedback may be a program’s goal, it may be important for programs to be sensitive to the realities of their program context and recognize that their program’s culture may not yet support open feedback (eg, a culture where bidirectional feedback is welcomed and there is no fear of retribution). This is consistent with previous findings10 and may also reflect the cultural challenges of graduate medical education noted by Ramani11 and Watling.2

This research is not without limitations. Participating programs were self-selected members of a pilot study to implement a mobile faculty feedback system; additionally, while they represent a mix of university- and community-based programs and regional variation, all are FM programs, which may limit transferability of themes.

PDs, faculty, and residents share a desire to provide faculty with meaningful, specific, real-time feedback. Programs should strive to provide a culture in which feedback is an integral part of the learning process for both residents and faculty. Next steps include piloting a mobile feedback tool to facilitate point-of-observation feedback from residents to faculty, incorporating the principles identified in this study.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest Statement: Cristen Page, a coinvestigator on this study, serves as chief executive officer of Mission3, the educational nonprofit organization that has licensed from UNC the tool, the F3App, which was evaluated in this study. If the technology or approach is successful in the future, Dr Page and UNC Chapel Hill may receive financial benefits.

References

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements (Residency) Section I-V. http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2019.

- Watling C, Driessen E, van der Vleuten CPM, Vanstone M, Lingard L. Beyond individualism: professional culture and its influence on feedback. Med Educ. 2013;47(6):585-594. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12150

- Harris DL, Krause KC, Parish DC, Smith MU. Academic competencies for medical faculty. Fam Med. 2007;39(5):343-350.

- Srinivasan M, Li STT, Meyers FJ, et al. “Teaching as a competency”: competencies for medical educators. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):1211-1220. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c5b9a

- Colletti JE, Flottemesch TJ, O’Connell TA, Ankel FK, Asplin BR. Developing a standardized faculty evaluation in an emergency medicine residency. J Emerg Med. 2010;39(5):662-668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.09.001

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Milestones. https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Milestones/Overview. Published 2018. Accessed April 10, 2019.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. The Core Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) for Entering Residency. https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/coreepas/. Published 2018. Accessed April 10, 2019.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA. 1983;250(6):777-781. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1983.03340060055026

- Afonso NM, Cardozo LJ, Mascarenhas OA, Aranha AN, Shah C. Are anonymous evaluations a better assessment of faculty teaching performance? A comparative analysis of open and anonymous evaluation processes. Fam Med. 2005;37(1):43-47.

- Ramani S, Könings KD, Mann KV, Pisarski EE, van der Vleuten CPM. About Politeness, Face, and Feedback: Exploring Resident and Faculty Perceptions of How Institutional Feedback Culture Influences Feedback Practices. Acad Med. 2018;93(9):1348-1358. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002193

Lead Author

Linda Myerholtz, PhD

Affiliations: Department of Family Medicine,University of North Carolina Chapel Hill

Co-Authors

Alfred Reid, MA - University of North Carolina Department of Family Medicine

Hannah M. Baker, MPH - Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill

Lisa Rollins, PhD - Department of Family Medicine, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA

Cristen P. Page, MD, MPH - Department of Family Medicine, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill

Corresponding Author

Linda Myerholtz, PhD

Correspondence: 590 Manning Drive CB# 7595, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7595. 919-962-4764. Fax: 919-843-3418.

Email: Linda_Myerholtz@med.unc.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.