Background and Objectives: There are several trends compelling physicians to acquire team-based skills for interprofessional care. One underdeveloped area of team-based skills for physicians is integrated behavioral health (IBH) in primary care. We used a Delphi method to explore what skills were needed for residents to practice integrated behavioral health.

Methods: We conducted a literature review of IBH competencies and found 41 competencies across seven domains unique to physicians. Using a modified Delphi technique, we recruited family medicine educators to rate each competency as “essential,” “compatible,” or “irrelevant.” We also shared findings from the Delphi study with a focus group for additional feedback.

Results: Twenty-one participants (12 physicians, nine behavioral health providers) completed all three rounds of the Delphi survey resulting in a list of 21 competencies. The focus group gave additional feedback.

Conclusions: Participants chose skills that required physicians to share responsibilities across the entire care team, were not redundant with standard primary care, and necessitated strong communication ability. Many items were revised to reflect team-based care and a prescribed physician role as a team facilitator. Next steps include determining how these competencies fit with a variety of medical providers and creating effective training programs that develop competency in IBH.

There are emerging trends in the US health care system compelling physicians to acquire team-based skills for interprofessional care, with growing evidence that connects team-based care with better patient outcomes.1 One underdeveloped area of team-based skills for physicians is integrated behavioral health (IBH), a multifaceted clinical approach to address the social, mental, and behavioral health needs of patient populations.2 IBH involves both medical and behavioral health clinicians working together to improve the health of patients and is especially applicable for primary care, known over the past 30 years as the “de facto mental health services system” in the United States.3,4 There is growing evidence that suggests IBH produces better outcomes than usual primary care in treating common mental disorders.5,6

Considering that a majority of primary care problems have behavioral health components, physicians need specific skills for IBH that both supplement general team-based skills of communication, mutual respect, and collaboration, and that also fit with effective clinical pathways of identifying and treating patients with behavioral health needs. Recent literature on interprofessional team-based care includes broad domains of collaboration and not skills specific to IBH.7 The Family Medicine Milestones use the word “team” 22 times in reference to team-based care (see Systems-Based Practice #4).8 However, there is no expert consensus on competencies for physicians working within IBH teams, leaving residency programs without guidance and limiting the dissemination of IBH standards of practice.

A first step in this endeavor is to identify the competencies for medical residents working within IBH. Competency-based medical education focuses on acquisition of skills and abilities across essential domains of medicine. Competency-based medical education helps faculty focus on specific outcomes and promotes learner-centered training that develops over time.9 Both the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) provide general guidelines for counseling skills and medication management for family medicine residents.10,11 However, these training guidelines do not adequately address the breadth of clinical and interpersonal skills unique to functioning effectively on IBH teams. Expanding family medicine competencies to include key elements of practicing integrated care is critical for physicians to work as effective team members.12,13 To date, there are no firmly established competencies that guide residents to learn specific team-based skills for behavioral health integration. We used a Delphi method to explore what skills are needed for residents to work effectively in primary care with behavioral health providers.

Competency Development Framework

Competency development is a time-intensive, deductive process that often begins with a review of published documents, especially by major stakeholder groups (eg, government agencies, accreditation bodies). The effort to create the graduate medical education core competencies serves as an example of an accepted, multistep development process.14 This consensus-driven process makes use of both the literature and content experts over several cycles. We followed the ACGME process by reviewing the medical education and workforce development literature using related search items.15

Reviewing the Literature

We found two published lists of competencies for medical and behavioral health providers practicing integrated behavioral health.16,17 The 2015 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) report is a literature review of provider- and practice-level competencies. The 2014 Center for Integrated Health Solutions (CIHS) report includes interviews of content experts, a literature review, and expert analysis to identify provider competencies (n=87). Neither report is considered specific to medical providers. We found two other lists of skills created for behavioral health providers only to identify any additional competencies for medical providers; both lists are products of work groups that reviewed the literature and discussed findings in person or through conference calls.18,19

After identifying these lists, we reviewed all lists to identify competencies with the following questions in mind: “Which of these items are unique to integrated behavioral health?” and “Which of these items are essential for medical providers learning to practice integrated behavioral health?” We identified 41 competencies that fit the criteria as being unique and essential and then created six domains based on a review of the domains used in the AHRQ and CIHS reports and placed each item into one of the six domains.

Surveying Experts: Delphi Technique

After selecting and classifying the 41 competencies, we chose a modified Delphi approach to seek expert consensus on competencies for family medicine residents working within a primary care team that incorporates behavioral health care. The Delphi technique builds consensus from a panel of selected experts.20 It employs multiple, sequential surveys, allowing participants to reassess their initial judgments, and provides anonymity to minimize bias and encourage participation. Electronic surveys delivered through email communication is an acceptable medium for Delphi studies.21 We followed the method used in another Delphi study examining integrated behavioral health.22 We used three rounds of survey data collection with the goal of reaching at least 80% consensus on each item. The Cape Fear Valley Hospital Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Survey Participants

To be included in the survey, experts must have worked 10 or more years as a graduate medical educator and 5 or more years in integrated behavioral health. Based on this criteria and recommendations from the study group, we identified 32 candidates to recruit for the survey. The project consultant (L.M.) was contracted, in part, to help identify study candidates. We sent email invitations to all candidates and 27 agreed to participate (five did not respond or declined). Twenty-four participants completed the first round of questions while 21 participants completed all three rounds of questions (attrition rate of 12%). In the final group, 12 participants were primary care physicians and nine were behavioral health professionals.

Survey Item Development

We recruited eight behavioral scientists to help in designing survey items and reviewing survey responses. We used the online survey tool SurveyMonkey to build the survey questions and collect responses. The survey draft was tested and refined by group members until a final draft was selected. Each survey included a list of items with ranking categories of “Essential”, “Compatible”, and “Irrelevant” used in another study.20 The first survey included 41 items, the second survey had 15 items, and the final survey had three items. The first-round survey included study information and a button to click indicating consent to participate. For the third round, we presented a list of all the items that were considered compatible and asked participants to determine if each item was a secondary or a primary competency for physician integrated behavioral health practice. We also presented a list of all the items that had thus far received 80% consensus.

Survey Procedure

After developing the survey and enrolling 27 participants, we sent out the first email message with a link to the survey. Participants read each item, rating it as “essential,” “compatible” or “irrelevant.” We encouraged participants to leave comments regarding their opinions or reflections on any survey items. Items that received 80% consensus were automatically saved as-is and recorded in the final list of essential competencies. Using participants’ comments about items that did not reach an 80% threshold, we discussed the removal, revision, or creation of new items. The second and third rounds included individual email messages to each participant with a copy of their previous survey responses, the overall response ratings from the group of participants, and our rationale for revising or creating new items. This iterative, bidirectional learning process allowed both the study group and the participants to learn from each other. Upon completion of the third survey round, we addressed the final comments and rankings to create a final list of competencies.

Confirming the Survey Results: Focus Group

Following the creation of the final list of competencies, we conducted a 30-minute focus group at a national conference on behavioral science in family medicine using a convenience sample of conference attendees who attended our presentation on the list of competencies. These attendees did not participate in the Delphi survey and we did not offer any incentive for them to participate. The purpose of the focus group was to validate the findings of the Delphi study and elicit feedback on the utility and application of the results. Audience members were divided into six groups based on where they sat in the conference room, consisting of five to seven people per group. Each focus group was facilitated by a study team member who elicited specific comments about a number of the competencies. Focus group members were asked to share their thoughts regarding whether or not they thought each competency was essential for medical providers learning to practice IBH. Participants also rated each competency on a scale of 1-5, with 5 indicating the competency was essential for practice. Each group facilitator summarized results from the focus group discussions at the end of the presentation. All field notes were collected and later analyzed as a group during subsequent conference calls using a thematic analysis approach to identify common recommendations from the focus group.

Delphi Process Findings

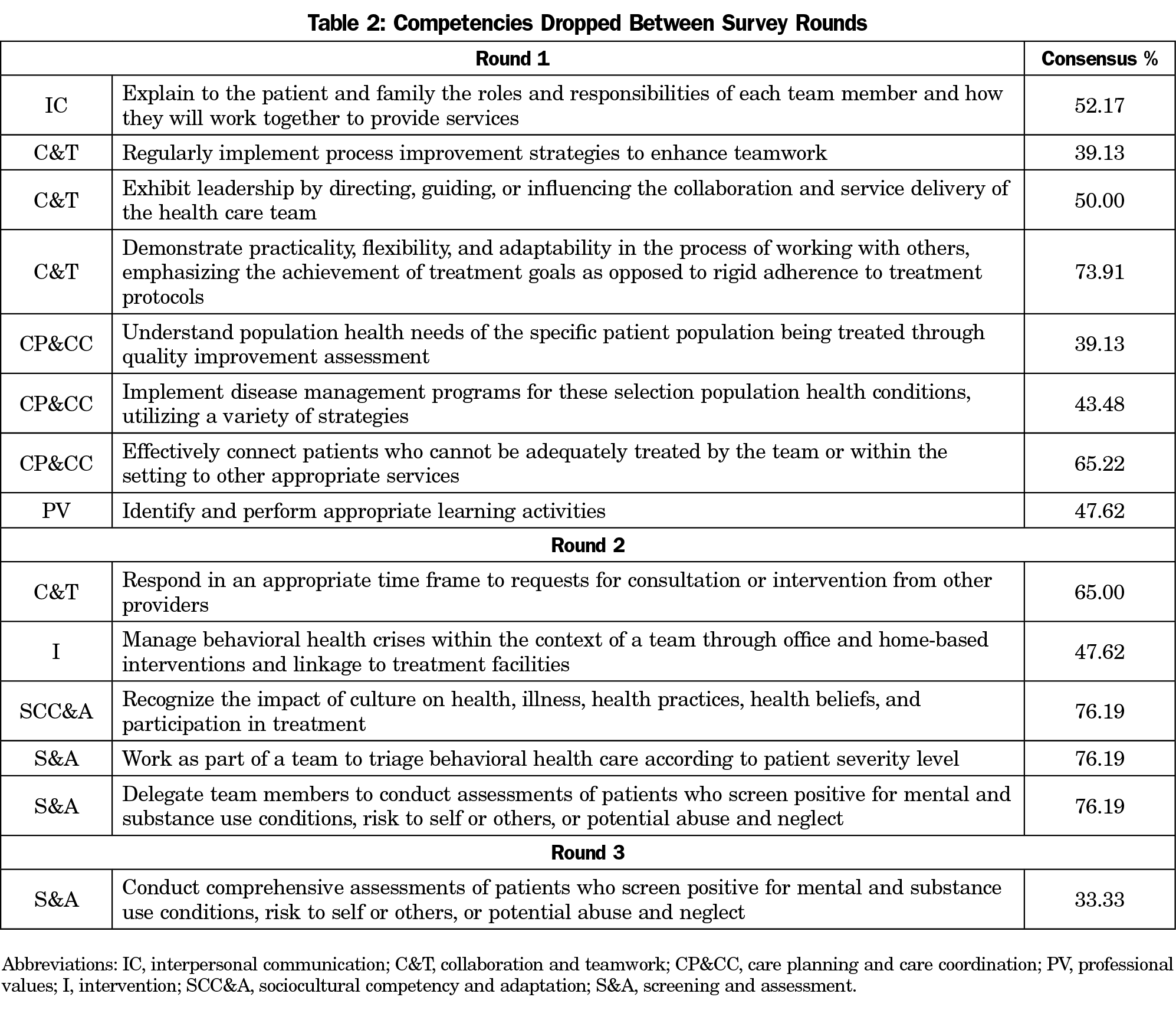

In the first round, 14 of 41 items received 80% consensus as essential. All items that received 80% consensus were saved as-is and recorded in the final list. After the first survey round, we removed eight items and revised or combined 19 items; we then presented 15 items during the second round. In the second round, 10 of the 15 items reached 80% consensus. After the second survey round, we removed five items and revised two items. In the final round, one of three reached 80% consensus. After the final survey round, we included the item that reached consensus and removed three additional items based on feedback from the expert panel and discussion from our research group. Many items were removed during the survey for one of two reasons: (1) the item was a core element of primary care and not unique to IBH; (2) the item was difficult to evaluate (eg, “Recognize the impact of culture on health”).

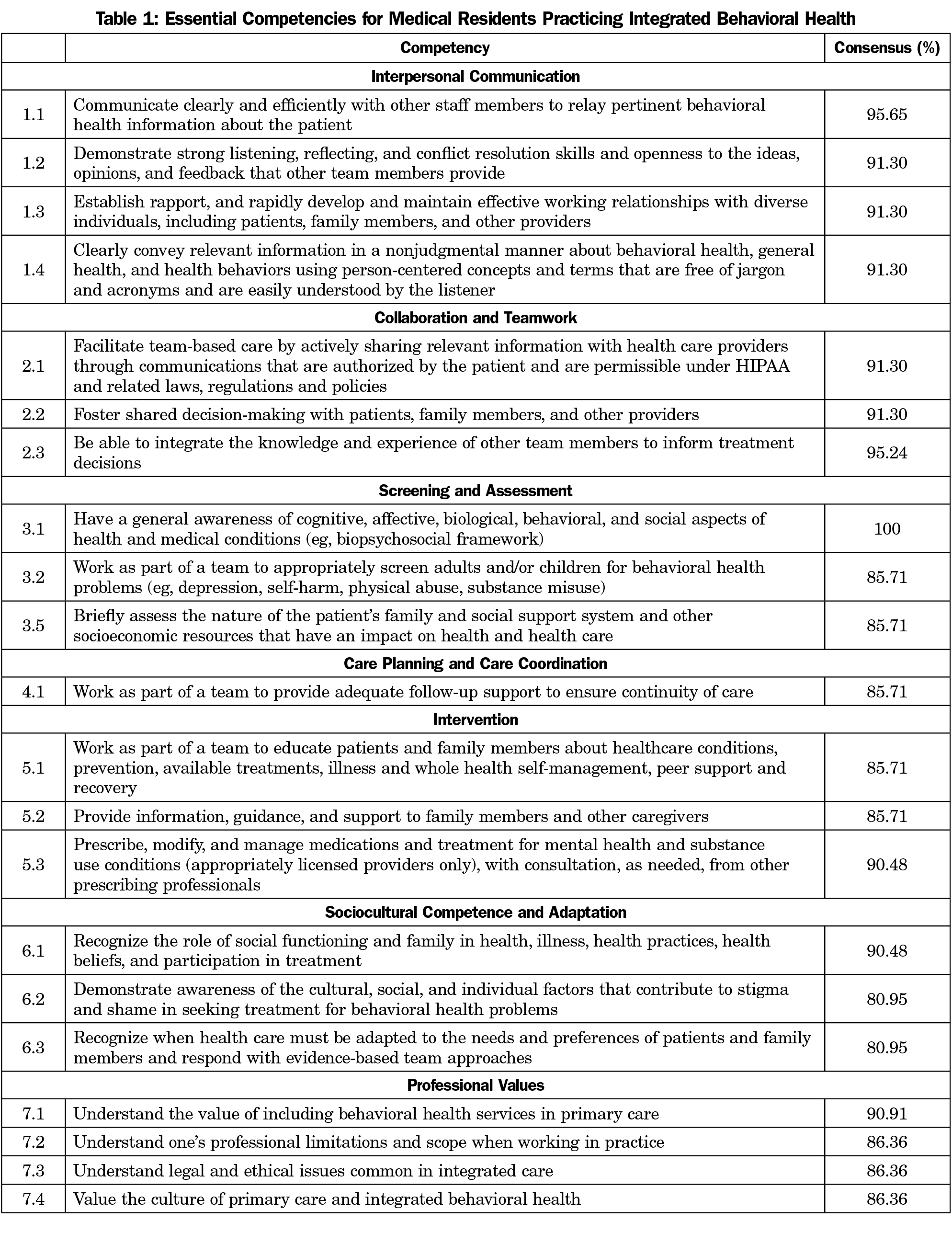

The final list includes 21 essential competencies in seven domains (Table 1). We removed 14 items in total between survey rounds (Table 2). The survey participant comments played a significant role in our decision-making process between rounds. Examples of comments from survey participants included reflections on how to integrate these competencies into the process of care, confusion about how to distinguish between essential and compatible, and questions about interprofessional roles. In the third survey round we asked participants to comment on a list of competencies that were considered compatible but not essential, and whether these competencies should be considered secondary skills in IBH. The participants agreed that the majority of the compatible competencies should be considered at least secondary, with some participants expressing surprise that certain items did not reach the 80% consensus to be considered essential.

Focus Group Findings

Results from focus groups indicated that nearly 90% of participants thought the competencies presented were essential for practice, scoring a 4 or 5 on a 5-point Likert scale, with a 5 indicating “very essential.” Two competencies, both from the “professional values” category, scored between 3 and 4. Focus group members remarked that many competencies were “essential for continuity care,” “essential collaborative skills,” and “definitely skills that residents and younger physicians need to know.” They also recommended developing specific behavioral anchors for each competency that supported skill development and evaluation. For example, participants identified competencies that were “hard to observe or track,” “vague,” and difficult to “judge from observation.” Based on feedback from the focus group, we revised two items in the “professional values” category and made plans to develop behavioral anchors for each competency.

Given the breadth of training required for primary care physicians during the 3 years of residency, it is important to focus curriculum on essential content. Our 21 competencies represent expert consensus on essential IBH skills for physicians to support curriculum and workforce development. The participants chose skills that require physicians to share responsibilities with the entire care team, use the abilities of behavioral health providers, and are observable. Unlike other behavioral health integration skill lists, these competencies were designed for the physician role, include skills that are not redundant with essential primary care, and are comprehensive but concise enough for effective training and evaluation.

While reviewing items that did not receive 80% consensus, participant responses revealed a few trends. First, participants preferred items that shared the responsibility of IBH across team members. Items like “Manage behavioral health crises within the context of a team through office- and home-based interventions and linkage to treatment facilities,” and “Conduct comprehensive assessments of patients who screen positive for mental substance use conditions, risk to self or others, or potential abuse and neglect” did not receive 80% consensus. In response, we revised several items to include the phrase “work as part of a team” to emphasize a team-based approach and, consequently, received higher consensus.

Second, participants preferred items that were specific to IBH and not redundant with standard primary care. Items like “Effectively connect patients who cannot be adequately treated by the team or within the setting to other appropriate services” and “Demonstrate practicality, flexibility, and adaptability in the process of working with others, emphasizing the achievement of treatment goals as opposed to rigid adherence to treatment protocols” were considered by participants as standard primary care practice and thus removed from the final list. Finally, participants did not give 80% consensus to any items that required physicians to use practice or quality improvement strategies. Items like “Regularly implement process improvement strategies to enhance teamwork” received some of the lowest consensus. This feedback is consistent with recent findings on the barriers to promoting quality improvement practice in primary care.23, 24

The final list of competencies describes a vital and specific role for physicians working with team members to share the majority of responsibilities like screening, care planning, and follow-up. These findings fit with other evidence that physicians can serve as effective task delegators in delivering preventive and chronic care services.25 The creation of these competencies is meant to help educators teach behavioral health teamwork skills. However, it is important to note that the creation of these competencies is not intended to displace the behavioral health skill learning essential for every family physician. Instead, these competencies help family physicians effectively manage the needs of a larger proportion of a population than is possible with only a behavioral health team.

The next steps for this research include at least two future studies. First, we can determine the fit of our competencies with other primary care disciplines by recruiting a large, diverse sample of medical providers in integrated care and collecting feedback on the appropriateness of the competencies in actual practice. Second, we can design and test a competency-based curriculum for primary care providers with evaluation strategies that measure competency over time. Residency training and other workforce development programs can use the curriculum to prepare providers for working in settings with behavioral health integration.

The strengths of our study include recruiting experts from both medicine and behavioral science. We also used multiple data sources (eg, current literature, expert opinion, and a focus group) to generate our findings. The combination of multiple sources allowed us to confirm our decisions using qualitative and quantitative feedback. Limitations include not collecting additional information from our experts (eg, demographic, experience with specific IBH models) and recruiting only within the United States. Participant opinion likely draws from their direct experience with particular health care systems within the United States. An inherent limitation of the Delphi technique conducted online is that it does not allow for in-person discussion and debate among the expert panel. However, conducting the focus groups with behavioral scientist educators in graduate medical education allowed us to obtain more feedback about the identified competencies. Finally, we recognize that these competencies are not exhaustive and even present challenges for residency programs that do not offer IBH services or lack the ability to evaluate resident performance in IBH.

The competencies of integrated behavioral health we identified are a promising tool that family medicine educators can use in residency training. They can also help guide development of faculty who have not previously worked in IBH settings, and identify IBH service gaps within a primary care system. ACGME Family Medicine Competencies have demonstrated the discipline’s core value of working with others, especially through partnering with patients and their families. As IBH becomes more of the norm, competency-based workforce development will be essential in preparing physicians to fulfill key roles as collaborators in addressing the behavioral health needs of their patients. We anticipate feedback from those who implement these competencies to help us refine and improve their value in graduate medical education.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following individuals who contributed to the design and implementation of this study: Allison Bickett, Jennifer Carty, Deepu George, Maureen Healy, Meredith Lewis, Samantha Minski. They also thank the following individuals who served on the expert panel: Amy Bauer, Sandy Blount, Tom Campbell, Colleen Fogarty, Kevin Fiscella, Debra Gould, Bill Gunn, Barry Jacobs, Rodger Kessler, Parinda Khatri, Alan Lorenz, Kim Marvel, Susan McDaniel, Laurel Milberg, Yvonne Murphy, Amy Odom, Andrew Pomerantz, Neftali Serrano, Beat Steiner, Kirk Strosahl, Mindy Udell, Bill Ventres, Mark Vogel, and Dael Waxman. The authors also appreciate the participation of focus group members at the 2017 Behavioral Science Forum in Chicago, Illinois who gave valuable feedback.

Financial Support: Funding for the Delphi study was provided by the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Project fund.

Presentations:

- Preparing Residents for Integrated Behavioral Health: Competencies and Behavioral Anchors. A 45-minute seminar given at the Integrated Healthcare Conference. March 6, 2018, Scottsdale, AZ.

- Preparing Residents for Integrated Behavioral Health: A Competency-Based Curriculum. A 60-minute seminar given at the STFM Practice Improvement Conference. December 1, 2017, Louisville, KY.

- Preparing Residents for Integrated Behavioral Health: A Competency-Based Curriculum. A 25-minute presentation given at the CFHA Annual Conference. October 20, 2017, Houston, TX.

- Preparing Residents for Integrated Behavioral Health: A Competency-Based Curriculum. A 60-minute seminar given at the Behavioral Science Forum. September 14, 2017, Chicago, IL.

References

- Schottenfeld L, Petersen D, Peikes D, Ricciardi R, Burak H, McNellis R, Genevro J. Creating patient-centered team-based primary care. AHRQ Pub. No. 16-0002-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. March 2016.

- Kwan BM, Nease DE. The state of the evidence for integrated behavioral health in primary care. In: Talen MR, Valeras AB, eds. Integrated Behavioral Health in Primary Care. New York: Springer; 2013:65-98. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6889-9_5

- Regier DA, Goldberg ID, Taube CA. The de facto US mental health services system: a public health perspective. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35(6):685-693. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300027002

- Kessler R, Stafford D. Primary care is the de facto mental health system. In: Kessler R, Stafford D, eds. Collaborative Medicine Case Studies. New York: Springer; 2008. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-76894-6_2

- Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006525.

- Martin MP, White MB, Hodgson JL, Lamson AL, Irons TG. Integrated primary care: a systematic review of program characteristics. Fam Syst Health. 2014;32(1):101-115. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000017

- IECE Panel. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: 2016 update. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative.

- Allen S. Development of the family medicine milestones. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(1s1): 71-73. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-06-01s1-06

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Milestones. http://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Milestones/Overview. Accessed February 7, 2018.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Recommended Curriculum Guidelines for Family Medicine Residents: Human Behavior and Mental Health. Reprint No. 270. https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/medical_education_residency/program_directors/Reprint270_Mental.pdf. Accessed February 7, 2018.

- Holmboe ES, Batalden P. Achieving the desired transformation: thoughts on next steps for outcomes-based medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90(9):1215-1223. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000779

- Holmboe ES, Ward DS, Reznick RK, et al. Faculty development in assessment: the missing link in competency-based medical education. Acad Med. 2011;86(4):460-467. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820cb2a7

- Frank JR, Mungroo R, Ahmad Y, Wang M, De Rossi S, Horsley T. Toward a definition of competency-based education in medicine: a systematic review of published definitions. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):631-637. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.500898

- Batalden P, Leach D, Swing S, Dreyfus H, Dreyfus S. General competencies and accreditation in graduate medical education. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(5):103-111. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.103

- Swing SR. The ACGME outcome project: retrospective and prospective. Med Teach. 2007;29(7):648-654. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701392903

- Kinman C, Gilchrist E, Payne-Murphy J, Miller B. Provider-and practice-level competencies for integrated behavioral health in primary care: a literature review. (Prepared by Westat under Contract No. HHSA 290-2009-00023I). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2015.

- Hoge M, Morris J, Laraia M, Pomerantz A, Farley T. Core competencies for integrated behavioral health and primary care. Washington, DC: SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions; 2014.

- McDaniel SH, Grus CL, Cubic BA, et al. Competencies for psychology practice in primary care. Am Psychol. 2014;69(4):409-429. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036072 PMID:24820690

- Miller BF, Gilchrist EC, Ross KM, Wong SL, Blount A, Peek CJ. Core competencies for behavioral health providers working in primary care. Prepared from the February 2016 Colorado Consensus Conference.

- Hsu C, Sandford BA. The delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess, Res Eval. 2007;12(10):1-8.

- Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008-1015. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01567.x

- Beehler GP, Funderburk JS, Possemato K, Vair CL. Developing a measure of provider adherence to improve the implementation of behavioral health services in primary care: a Delphi study. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-19

- Bitton A. Finding a parsimonious path for primary care practice transformation. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(suppl 1):S16-S19. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2234

- Altschuler J, Margolius D, Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Estimating a reasonable patient panel size for primary care physicians with team-based task delegation. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(5):396-400. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1400

There are no comments for this article.