Background and Objectives: Most family medicine residency training takes place in hospitals, which is not reflective of the outpatient care practiced by most primary care clinicians. This pilot study is an initial exploration of family medicine residency directors’ opinions regarding this outpatient training gap.

Methods: The authors surveyed 11 California family medicine residency program directors in 2017-2018 about factors that influence decisions regarding allocation of residents’ inpatient and outpatient time. Nine of the 11 program directors agreed to be interviewed. We analyzed the interviews for common themes.

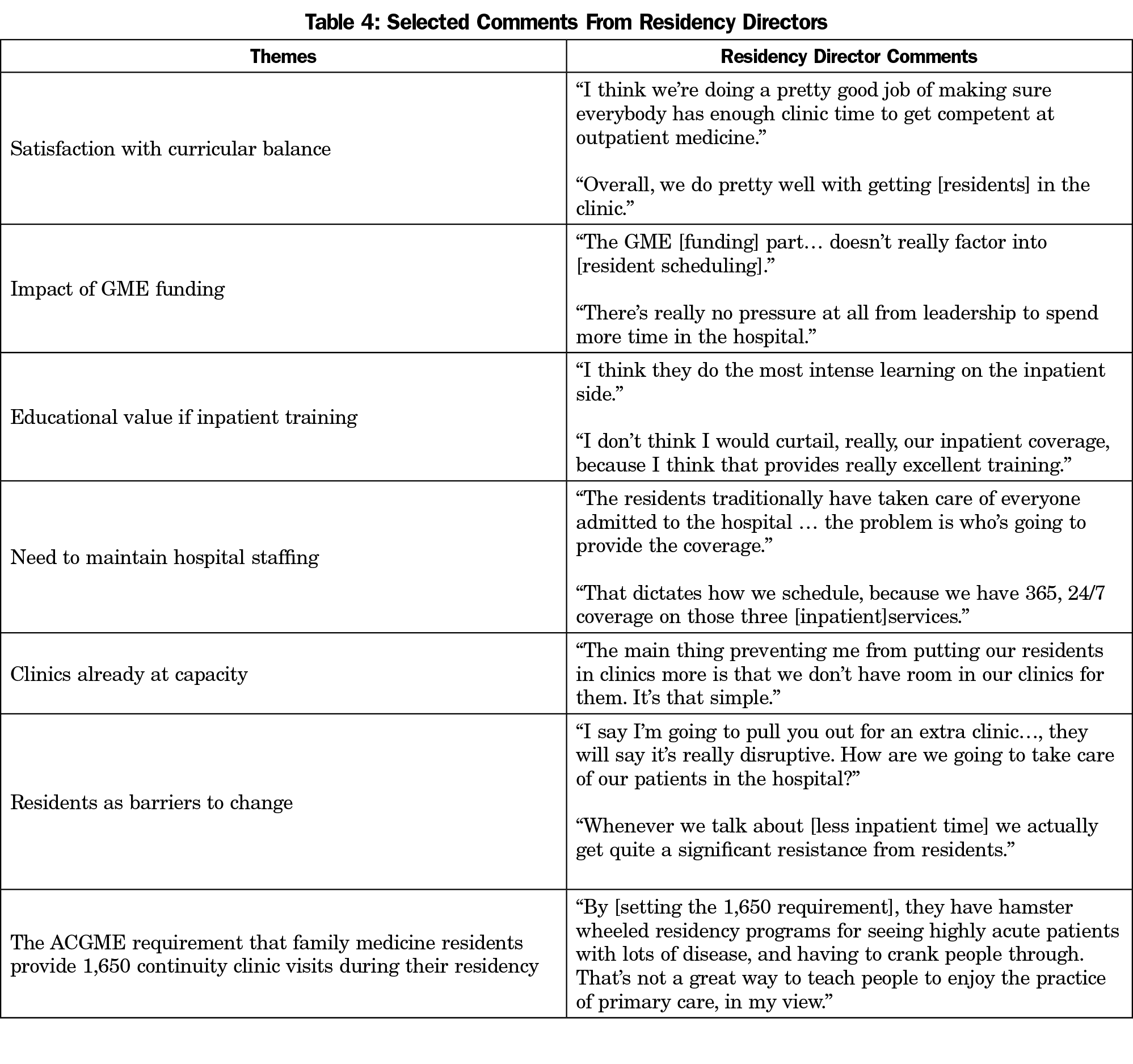

Results: The participating program directors were generally satisfied with inpatient and outpatient balance in their residents’ schedules. Factors identified as promoting inpatient training included the need for resident staffing of hospital services, the educational value of inpatient rotations, and a lack of capacity in continuity clinics. From the program directors’ perspective, residency funding played no direct role in curriculum planning. Program directors also felt that the ACGME requirements prescribing 1,650 continuity clinic visits throughout residency inhibited the development of creative outpatient training opportunities.

Conclusions: Family medicine residency program directors participating in this exploratory study did not feel that their programs overly emphasized inpatient care and training.

Americans receive the majority of their health care in an outpatient setting, yet most graduate medical education takes place in hospitals. In particular, the discrepancy between primary care residency training and career practice leaves many graduates inadequately prepared to begin an outpatient career.1,2 2011 data from the American Medical Association shows that, on average, family medicine residents only spend about one-third of their training in ambulatory settings.3 Addressing this outpatient training gap could help to harmonize family medicine residency training with the scope of practice of family physicians throughout their careers.

Much has been written about factors that might bias graduate medical education (GME) training toward inpatient medicine. Historically, most clinical training occurred in hospitals, where “house officers” cared for ill patients.4 This inpatient focus became the culture of medical education despite an increasingly outpatient-based medical landscape.2 In addition, the GME funding structure incentivizes hospital training. Medicare heavily finances residency programs with over $10 billion per year. These funds are allocated to hospitals sponsoring residency programs, rather than to residency programs themselves.5 Tying funding to hospitals discourages ambulatory training, where most people now receive care.6 Family medicine is most impacted by the hospital-first orientation of most residency training, since only 28% of recently graduated family physicians practice in-patient medicine.7

We hypothesized that family medicine residency directors would agree that (1) there is an outpatient training gap and that residents’ ambulatory time should increase; and (2) the outpatient training gap is the result of how GME is funded, with most funding directed to hospitals rather than to residency programs, giving hospitals control over the allocation of residents’ time. As an exploratory pilot study, we surveyed and interviewed California family medicine residency directors to obtain their views on the outpatient training gap.

We invited program directors from all 55 nonmilitary family medicine residency programs in California to participate in the pilot. We sent personalized email invitations from October 2017 through March 2018, with up to two reminder emails to nonrespondents. Participation was voluntary and uncompensated. The University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board designated the study exempt.

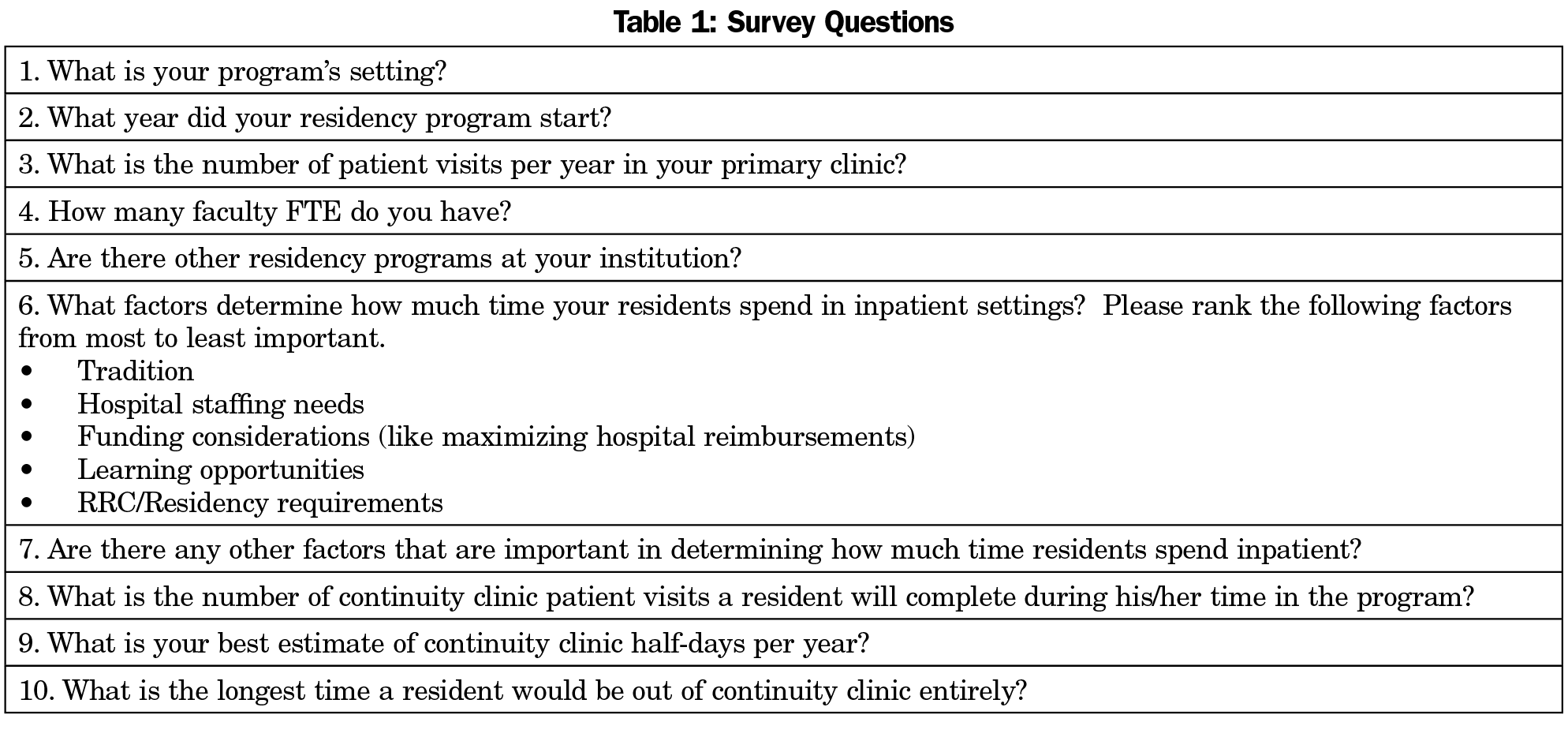

If the program director agreed to participate, we sent an information sheet and confidential survey link. The survey contained nine questions about the demographics of the residency program, as well as a request to rank several factors in order of influence on inpatient/outpatient scheduling (Table 1). This questionnaire informed follow-up interviews.

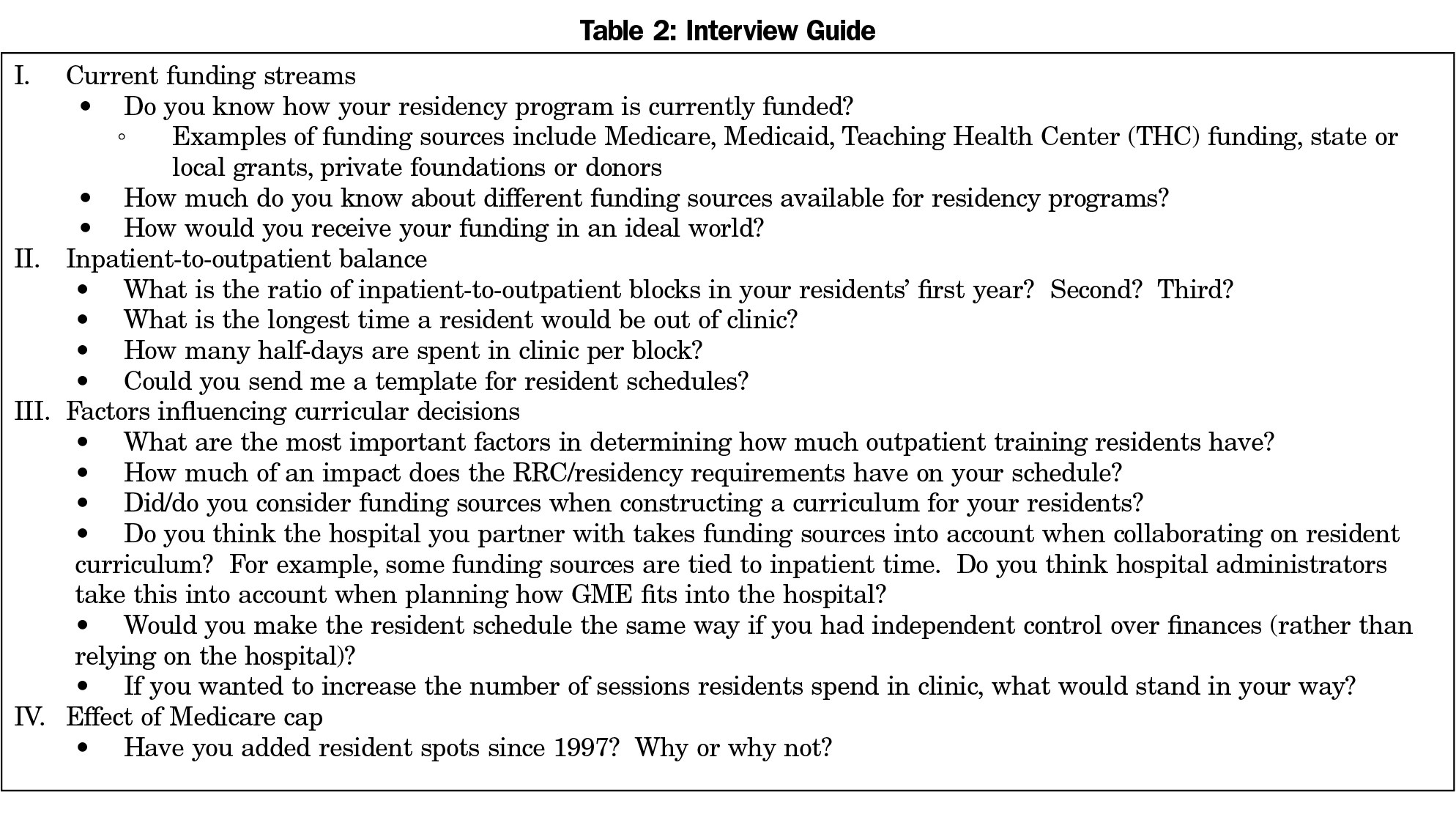

We asked all respondents who answered the survey to participate in a telephone interview. We used an interview guide developed from two pilot interviews (Table 2). All interviews were recorded and transcribed. Two authors independently coded transcripts to identify common codes and develop themes. Coding was done using Atlas.ti software, version 8.0 (https://atlasti.com). The mean and ranges of survey responses were calculated using Microsoft Excel.

Survey Responses

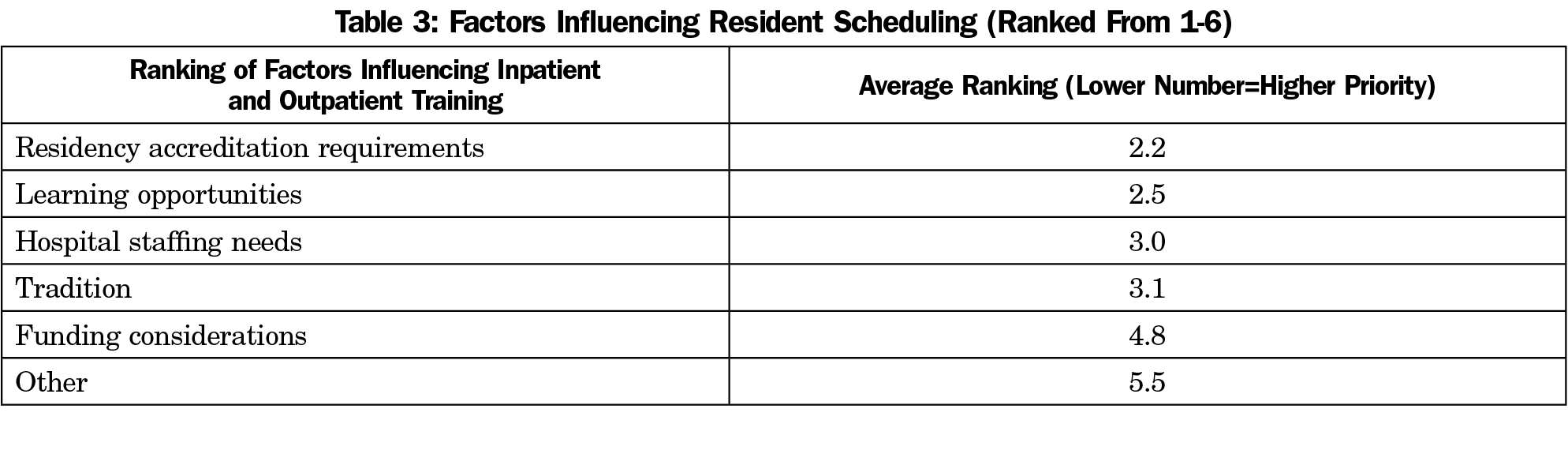

Of the 55 California program directors contacted, 11 completed the survey (20% response rate), and nine of those (16% response rate) completed an interview. In response to “What factor is most important when setting your residents’ schedules?” respondents ranked accreditation requirements highest, followed by learning opportunities, hospital staffing needs, tradition, and lastly, funding considerations (Table 3). The program directors interviewed were generally satisfied with the inpatient and outpatient balance in their residents’ schedules. Selected comments from the residency director interviews are provided in Table 4.

In 2014, the Institute of Medicine published a seminal report on graduate medical education, stating that “By distributing funds directly to teaching hospitals, the Medicare payment system discourages physician training outside the hospital, in clinical settings where most health care is delivered.”1 Yet we found that family medicine program directors participating in our study did not feel that inpatient care was overemphasized, and did not consider the impact of graduate medical education financing in prioritizing inpatient rotations over clinic time. The program directors tended not to view their programs as inpatient-heavy, valued the knowledge gained during hospital rotations, and felt that the residents had sufficient ambulatory training.

Program directors do not view inpatient rotations as competing with clinic time, perhaps because family medicine residents need competency in a broad scope of practice.

Recently, interest has grown in the Clinic First concept that places greater priority on ambulatory care and teaching.8 Clinic First does not imply that in-patient care should be second, but rather proposes actions that improve clinic functioning, such as designing resident schedules to enhance continuity of care, having fewer faculty physicians spending more time in the clinic, building stable primary care teams, engaging residents as coleaders in practice improvement, and increasing resident time in clinic. Perhaps the last principle—increasing resident clinic time—needs to be reevaluated given the opinions of the residency directors reported here.

The major limitation of this pilot study is the small number of residency directors who participated, their confinement to California, and the fact that they did not constitute a representative sample of family medicine residency directors. Moreover, a multistakeholder perspective— including clinic medical directors, residents, and faculty—may have revealed different opinions regarding the outpatient training gap. In particular, clinic medical directors, whose responsibility is focused on the clinic rather than the residency as a whole, may be more concerned with the gap. It is not possible to generalize from the small number of program directors’ responses because there is likely bias in the responses based on who chose to participate in the pilot study. Further research to explore opinions on the in-patient/ambulatory balance would require a larger national sample of family medicine residency directors or of multiple stakeholders.

We hypothesized that family medicine residency directors would agree (1) that there is an outpatient training gap and that residents’ ambulatory time should increase, and (2) that the outpatient training gap is the result of how graduate medical education is funded. However, the family medicine residency program directors participating in this study did not feel that their programs overly emphasized inpatient care and teaching, nor did they feel that graduate medical education financing has a role in prioritizing inpatient rotations over ambulatory care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the UCSF Center for Excellence in Primary Care (CEPC), including Rachel Willard-Grace and Beatrice Huang. This study was presented at the UCSF Family and Community Medicine Rodnick Colloquium on May 31, 2018.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by funding from the UCSF Primary Care Leadership Academy Fellowship.

References

- Institute of Medicine. Graduate Medical Education That Meets the Nation’s Health Needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2014. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2014/Graduate-Medical-Education-That-Meets-the-Nations-Health-Needs.aspx. Accessed November 20, 2019.

- UCSF Center for Excellence in Primary Care. High-Functioning Primary Care Residency Clinics: Building Blocks for Providing Excellent Care and Training. Washington DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2016. https://store.aamc.org/high-functioning-primary-care-residency-clinics.html. Accessed November 20, 2019.

- Wynn BO, Smalley R, Cordasco KM. Does It Cost More to Train Residents or to Replace Them? A Look at the Costs and Benefits of Operating Graduate Medical Education Programs. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2013.

- Howell JD. A History of medical residency. Rev Am Hist. 2016;44(1):126-131. https://doi.org/10.1353/rah.2016.0006

- United States Government Accountability Office. Physician Workforce: HHS Needs Better Information to Comprehensively Evaluate Graduate Medical Education Funding; 2018.

- Chen C, Xierali I, Piwnica-Worms K, Phillips R. The redistribution of graduate medical education positions in 2005 failed to boost primary care or rural training. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(1):102-110. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0032

- Weidner AKH, Phillips RL Jr, Fang B, Peterson LE. Burnout and scope of practice in new family physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):200-205. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2221

- Gupta R, Barnes K, Bodenheimer T. Clinic First: 6 actions to transform ambulatory residency training. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(4):500-503. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-15-00398.1

There are no comments for this article.