Although 5.2% of family physicians are sued for malpractice annually,1 there is no specific family medicine training or curriculum guidance on malpractice litigation.2,3 Other medical specialties have used mock trials to educate residents about malpractice litigation.4-8 We present the results of a collaboration with Penn State Dickinson School of Law (DSL) to develop a mock trial experience to fill a malpractice litigation training gap in our residency.

BRIEF REPORTS

Mock Trial as a Learning Tool in a Family Medicine Residency

Robert P. Lennon, MD, JD | Karl T. Clebak, MD | Jonathan B. Stepanian, JD | Timothy D. Riley, MD

Fam Med. 2020;52(10):741-744.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2020.405328

Background and Objectives: Mock trials have been used to teach medical learners about malpractice litigation, ethics, legal concepts, and evidence-based practice. Although 5.2% of family physicians are sued for malpractice annually, there is no formal requirement nor curriculum for educating our residents about malpractice, and mock trial has not been reported as an education modality in a family medicine residency. We developed a mock trial experience to educate family medicine residents about malpractice litigation and evaluated the resident experience over 3 years.

Methods: This is a retrospective, single-site study evaluating resident experience in our mock trials. We assessed perceived value using a 5-point Likert scale; and we assessed knowledge with free-text answers to both open and closed questions. We used descriptive statistics to describe data.

Results: Residents found the mock trial effective and engaging, giving the experience an overall evaluation of 4.9/5±0.3; 86.4% identified the importance of documentation as a learning outcome; 72.7% of residents identified negligence as necessary to justify a lawsuit, but they demonstrated limited mastery of the four elements of negligence, with 45.5% correctly listing harm, 40.9% causation, 13.6% breach of duty, and 0% duty owed.

Conclusions: Mock trial is an enjoyable and effective tool to engage residents and provide a general understanding of malpractice litigation. It is less effective in conveying nuanced details of negligence. It may also be effective in teaching practice management techniques.

The Penn State Institutional Review Board deemed this retrospective single-site study exempt. The case used is based on a real malpractice suit; we used redacted copies of actual case documents. Third-year residents were given 8 hours of protected time scheduled to complete the mock trial itself. Trial preparation time came from existing administrative time. Residents were assigned as the defendant or as a witness. Law students served as counsel. Participants received preparatory material that included complaints, statements, and records, as well as articles on reducing malpractice risk9 and expert witness testimony.10 Each side’s team of law students and residents were required to meet for trial preparation.

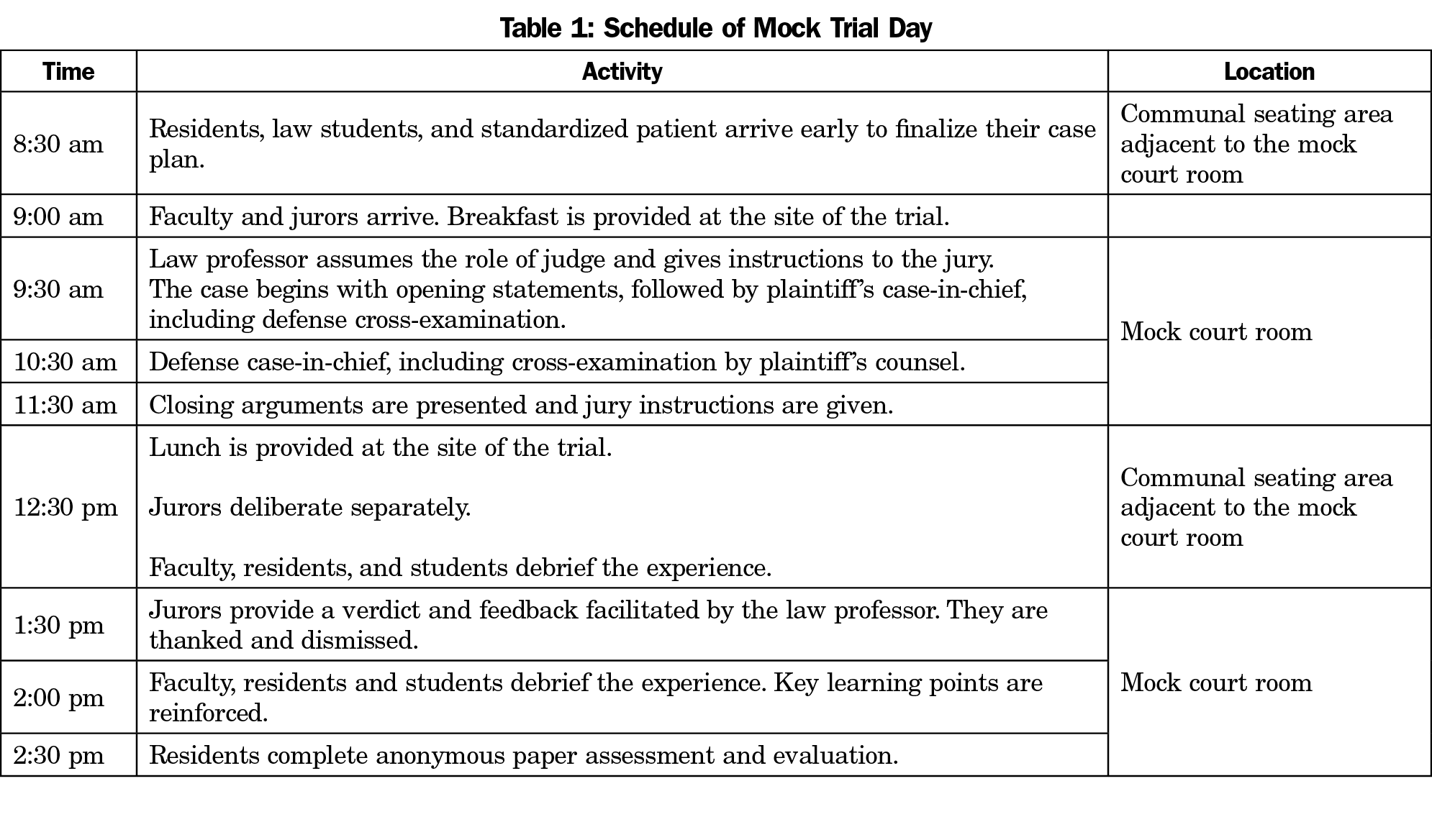

The plaintiff was played by a standardized patient from Penn State Hershey Medical Center. Community volunteers served as jurors. Law school faculty acted as judge, and trials were held in a mock courtroom at DSL (Table 1). The mock trial included jury instructions, opening statements, case presentations, witness examination, closing arguments, and jury instructions.

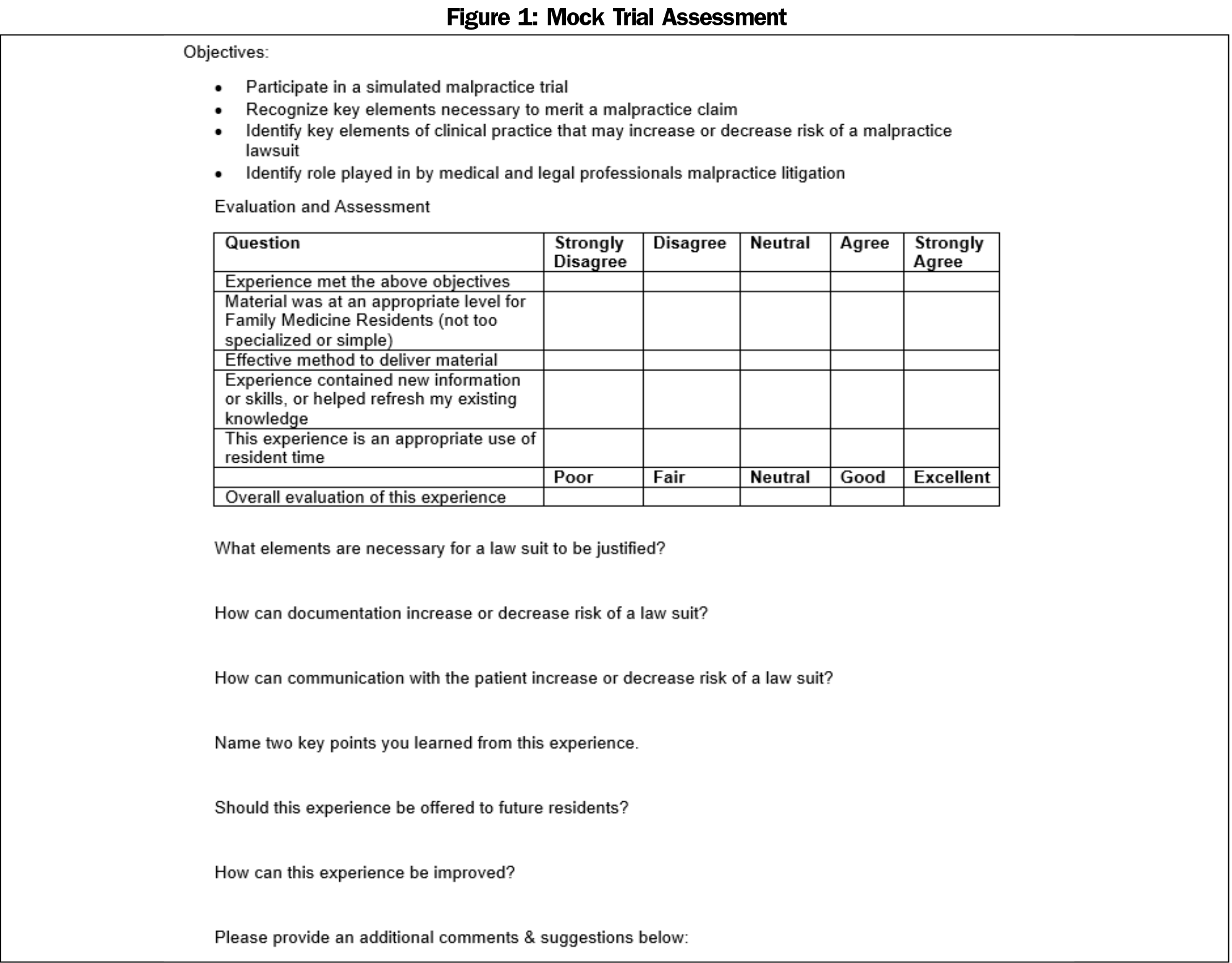

After the verdict was read, faculty facilitated discussion with the jurors regarding their impressions of the case. Residents completed an assessment (Figure 1). We used descriptive statistics to describe answers and grouped free-text answers into qualitative themes; answers consistent in language or intent for each element were counted as correct.

Over 3 years and six trials, 22 residents participated with 100% survey completion. On a 5-point scale, residents reported that the experience met its objectives (4.6±0.9), presented material at an appropriate level (4.7±0.9), was an effective method of teaching (4.6±0.9), presented new information or refreshed existing knowledge (4.6±0.9), and was an appropriate use of time (4.5±1.0), with an overall evaluation of 4.9±0.3.

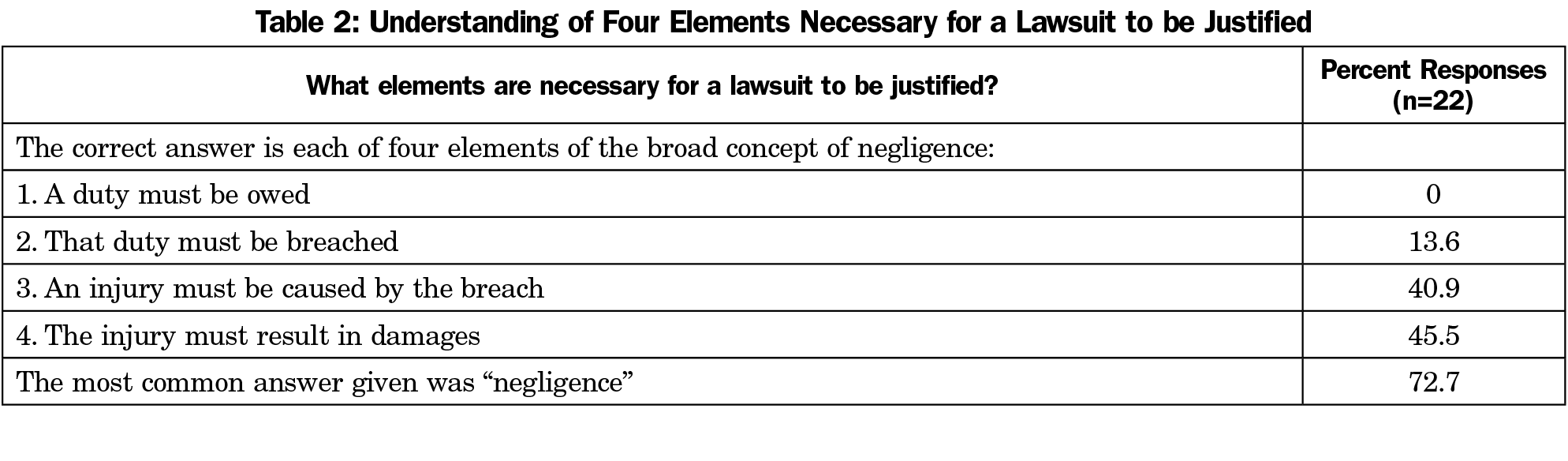

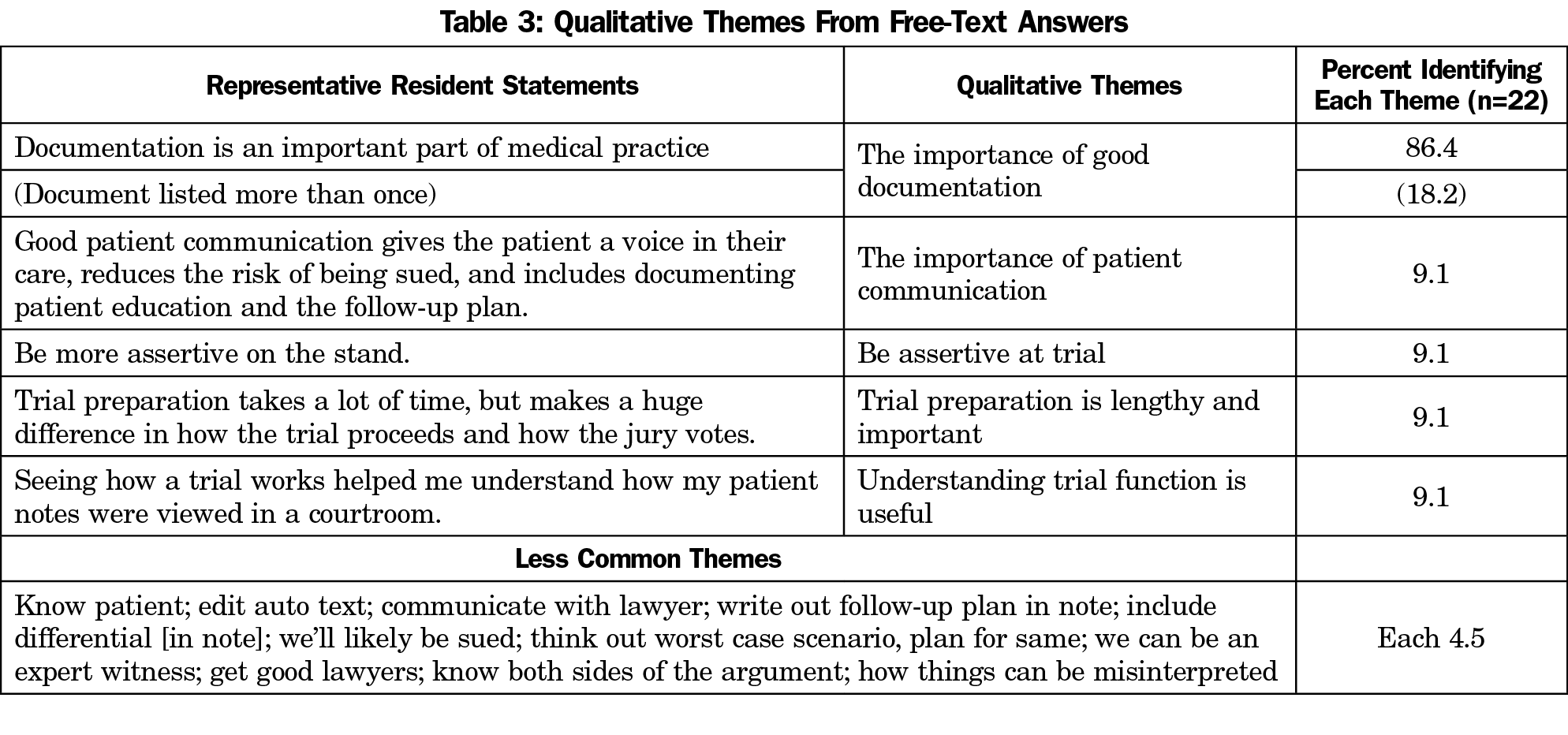

Residents did not demonstrate a good understanding of the elements necessary for a negligence lawsuit to be justified (Table 2); 72.7% of residents listed negligence as an element. The questions about how documentation and patient communication changes a risk of lawsuit did not yield cohesive themes. Several qualitative themes emerged from other free-text answers (Table 3), including the importance of proper documentation (86.4%), clear communication with patients (9.1%), self-assertion in the trial process (9.1%), and trial preparation (9.1%), as well as a better understanding of how trials function (9.1%). Suggestions for improvement included more time to prepare (22.7%), hold at better time of year (18.2%), provide more explicitly dedicated time to meet with the law team (13.6%), and make the event a multiyear process using dedicated didactic time (9.1%).

Residents reported that they learned or reinforced important medicolegal concepts and that future residents would benefit from the mock trial experience. They did not distinguish the elements of negligence. Negligence is required for a lawsuit to be successful, but the question was to identify the elements of negligence: a duty must have been owed, the duty must have been breached, an injury was caused by the breach, and the injury must result in damages.11 Many residents recognized the need to show injury and causation, but few identified the need for breach of duty, and none identified the need to show that a duty was owed. This identifies a learning gap, as understanding these elements can change the structure of medical practice and the nature of physician-patient interactions.

Qualitative assessment of resident answers to how documentation and patient communication change the risk of lawsuit did not identify common themes. Free-text qualitative themes (Table 3) indicate the wide range of learning mock trials may support. Although residents’ responses to how documentation would impact the risk of a lawsuit were not illustrative, virtually all residents identified the importance of documentation as a key learning point. They also learned to appreciate care and communication and the importance of clearly articulating a follow-up plan. These responses suggest that the importance of good practice management may be taught using mock trial. This would be a novel application of mock trial, which to date has focused on teaching trial preparation, ethics, and evidence-based medicine.12-14

The qualitative theme of being assertive at trial suggests that it may be meaningful to consider the mock trial experience from the perspective of developing professional self-esteem in residents. This may help residents cope with their fear of being sued, and with the emotional trauma experienced by physicians when they are sued. This could include adding a session on fear and professional self-esteem facilitated by a physician who has been sued.

The generalizability of our findings may be limited by our small sample size, single site, and program resources: a physically proximate law school willing to participate and a model patient compensated by our institution. However, remote programs may be able to overcome proximity with teleconferencing, use of young lawyers instead of law students, and unpaid volunteers (junior residents, other faculty, and community members) might serve as a plaintiff. Another limitation is that the data set does not include pre/post testing, which could help minimize social desirability bias. A strength of our study is that it covers 3 years of data, suggesting that the positive outcomes are stable over time.

In summary, our results suggest that mock trial may be an effective learning tool for family medicine residents. Future research might qualitatively evaluate residents’ learning related to patient communication and documentation and explore the use of mock trial to teach practice management strategies. Adding pre/post testing to better assess quantitative data and shifting the primary desired outcome to be professional development—in particular professional self-esteem—may also prove beneficial.

References

- Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, Chandra A. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(7):629-636. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1012370.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements (Residency). Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2018.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2019.

- Baker SE, Ogundipe K, Sterwald C, Van Enkevort EA, Brenner A. A winning case? assessing the effectiveness of a mock trial in a general psychiatry residency program. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(5):538-541. doi:10.1007/s40596-019-01065-3.

- Drukteinis DA, O’Keefe K, Sanson T, Orban D. Preparing emergency physicians for malpractice litigation: a joint emergency medicine residency-law school mock trial competition. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(1):95-103. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.08.017.

- Gilbert WM, Fadjo DE, Bills DJ, Morrison FK, Sherman MP. Teaching malpractice litigation in a mock trial setting: a center for perinatal medicine and law. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(3):589-593. . published Online First: 2003/03/15. doi:10.1097/00006250-200303000-00028

- Glancy GD. The Mock Trial: Revisiting a Valuable Training Strategy. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2016;44(1):19-27.

- Juo Y-Y, Lewis C, Hanna C, Reber HA, Tillou A. An innovative approach for familiarizing surgeons with malpractice litigation. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(1):127-133. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.06.002

- Achar S, Wu W. How to reduce your malpractice risk. Fam Pract Manag. 2012;19(4):21-26.

- Andrew LB. Expert witness testimony: the ethics of being a medical expert witness. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2006;24(3):715-731. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2006.05.001.

- Owen DG. The five elements of negligence. Hofstra Law Rev. 2007;35(4):1671.

- Centrella-Nigro AM, Flynn D. Teaching evidence-based practice using a mock trial. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2012;43(12):566-570. doi:10.3928/00220124-20120917-27.

- Ford CD, March AL, Cheshire M, Adams MH. Live versus DVD mock trial: are cognitive and affective changes different? Nurs Educ Perspect. 2013;34(5):345-347. doi:10.5480/1536-5026-34.5.345.

- Staffileno BA, McKinney C. Utilizing a mock trial to demonstrate evidence-based nursing practice: a staff development process. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2010;26(2):73-76. doi:10.1097/NND.0b013e3181d47aab.

Lead Author

Robert P. Lennon, MD, JD

Affiliations: Penn State College of Medicine, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Hershey, PA

Co-Authors

Karl T. Clebak, MD - Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, PA

Jonathan B. Stepanian, JD - Dickinson School of Law, Pennsylvania State University

Timothy D. Riley, MD - Department of Family and Community Medicine, Pennsylvania State University, Hershey, PA

Corresponding Author

Robert P. Lennon, MD, JD

Correspondence: Penn State College of Medicine, Department of Family and Community Medicine, 700 HMC Crescent Road, Hershey, PA 17033. 904-588-2621. Fax: 717-531-4327.

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.