Background and Objectives: Substance use disorders (SUD) remain a public health crisis and training has been insufficient to provide the skills necessary to combat this crisis. We aimed to create and study an interactive, destigmatizing, skills-based workshop for medical students to evaluate if this changes students’ self-reported knowledge, skills, and attitudes toward patients with SUD.

Methods: We surveyed students on a required family medicine outpatient rotation at a Pacific Northwest medical school during clerkship orientation on their views regarding SUDs utilizing the validated Drug and Drug Problems Perceptions Questionnaire containing a 7-point Likert scale. After attending a substance use disorder workshop, they repeated the survey. We calculated differences between the paired pre- to postsurveys.

Results: We collected the pre- and postdata for 118 students who attended the workshop and showed statistically significant positive differences on all items.

Conclusions: The positive change in the medical students’ reported attitudes suggests both necessity and feasibility in teaching SUD skills in a destigmatizing way in medical training. Positive changes also suggest a role of exposing students to family medicine and/or primary care as a strategy to learn competent care for patients with substance use disorders.

In 2014, 20.2 million adults in the United States had a substance use disorder (SUD) and only 7.5% received treatment.1 Gaps in treatment remained in 20182 and overdose deaths are increasing.3 Negative attitudes toward patients with SUD contribute to this gap4,5 and create barriers for physicians to obtain skills to improve these inequities.6 These biases are formed early in life, reinforced by social stereotypes, prevalent amongst health care workers, and linked to care inequities.7-9 As medical students harbor biases9 from past experiences, students agree SUDs should be addressed in medical education.10 While this knowledge may increase with medical training, poor confidence and negative attitudes remain in practice.11-12 More than 50% of patients report that their primary care provider did not address their substance use,10 showing skills deficits and creating an opportunity for family medicine (FM) educators to use their broad lens to improve care.

Calling attention to one’s bias and taking active steps to individuate treatment is a strategy to improve inequities,7,9 and curricula to reframe SUD as a medical disease are needed. Lack of faculty expertise, time, or requirements from accrediting organizations13 limit access to this training, even though such workshops can improve attendees’ knowledge, attitudes, skills, and confidence toward the care of patients with SUD.6,13-18 We therefore hypothesized that an FM clerkship workshop for medical students to reframe SUD as a treatable medical disease would improve their self-reported knowledge, skills, and attitudes towards this care.

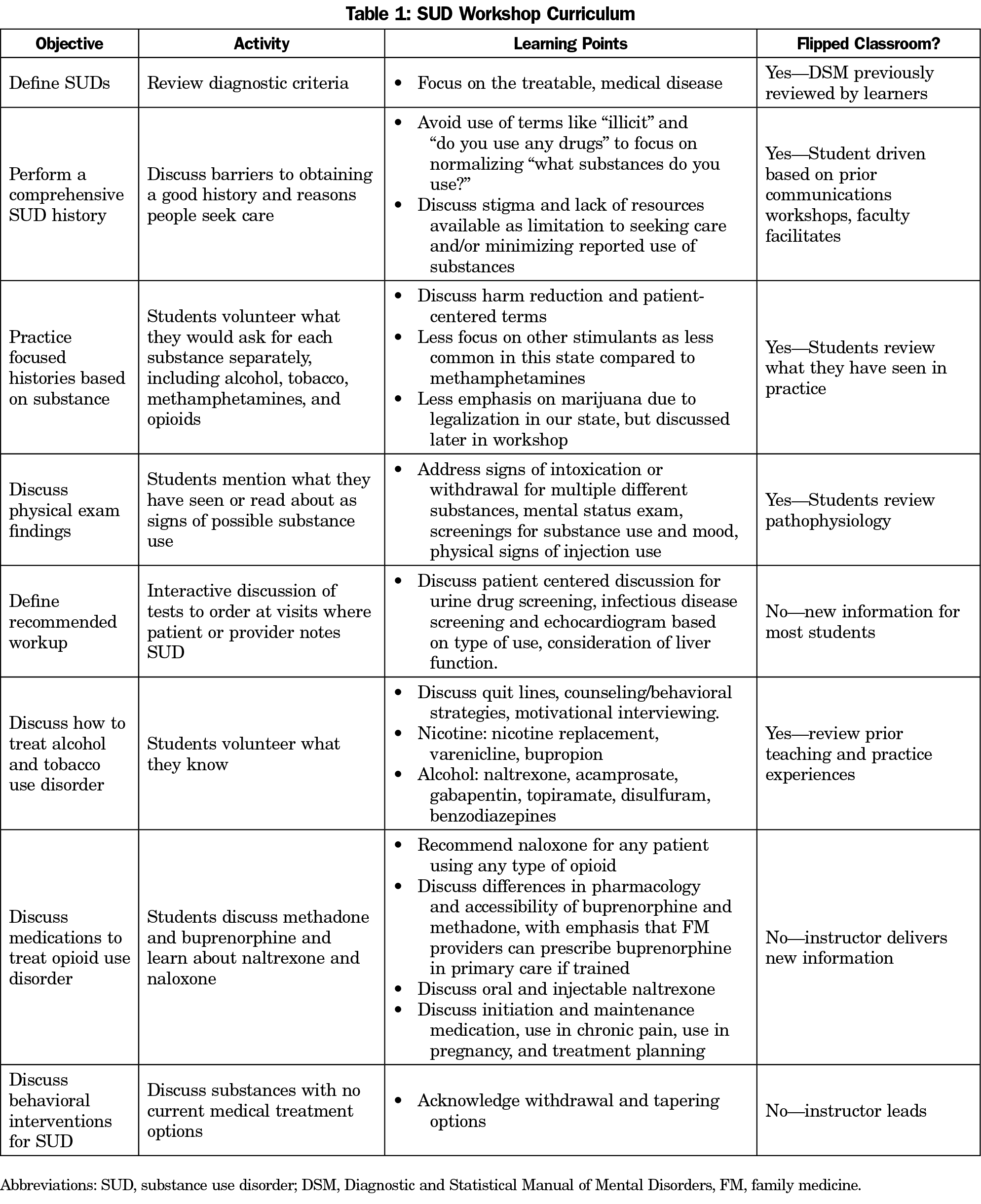

The SUD workshop was designed as one of many weekly didactics during a required 4-week FM clerkship at a Pacific Northwest medical school. Faculty physicians with experience in SUD treatment and education developed the curriculum utilizing a flipped-classroom model to engage learners in a patient-centered approach to practice history taking, focus on SUD as a treatable medical diagnosis, address stigma, and understand recommendations for treatment in primary care (Table 1).

The study included 295 medical students enrolled in one FM clerkship between January 2018 and December 2019, and received institutional review board approval. Student demographics were not collected to maintain anonymity to the clerkship director; however, the student body has an average age of 26 years, is over 50% female-identifying, and over 80% have Oregon residency or heritage.19

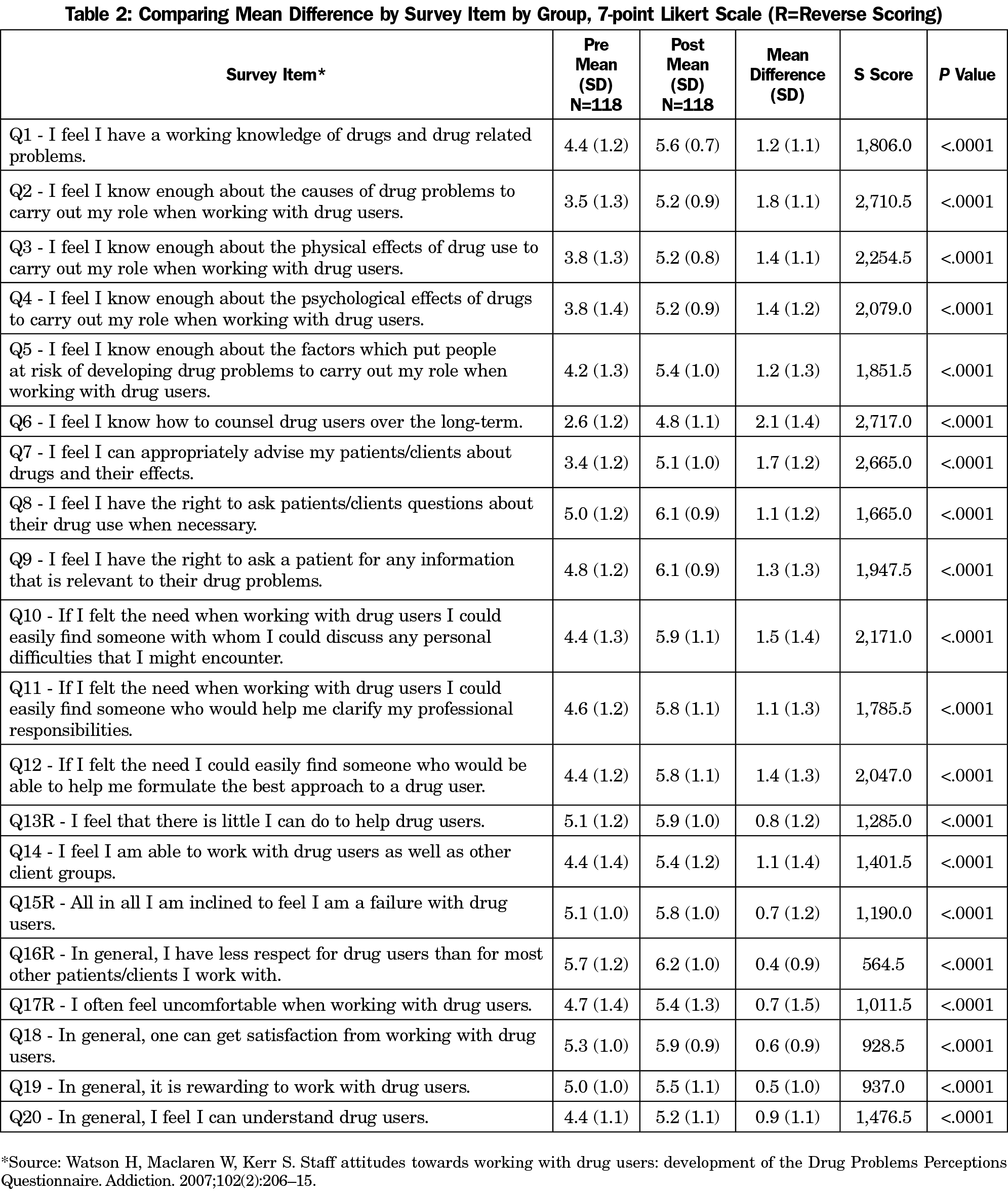

We selected the 20-question, 7-point Likert scale Drug and Drug Problems Questionnaire (DDPPQ) as it was more patient-centered than other validated scales, despite some outdated terms.20-22 To preserve validity, language was not altered. We gave students this questionnaire (Table 2) at clerkship orientation, and again after the workshop (3 weeks later) in person or via email. We paired surveys by unique identifiers to observe changes via a pretest-posttest study design. To account for different starting scores due to prior experiences, we reported changes instead of the discrete number on the Likert scale. We reverse-scored items 13, 15, 16, and 17. We discarded surveys that could not be paired due to nonmatching identifiers or lack of both surveys. We compared differences in pre- and postscores using a one-sided Wilcoxon Signed Rank Sum test using SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) to observe if there was a positive shift in scores, defined as a change in the DDPPQ Likert scale in a direction of more positive self-reported knowledge, skills or attitudes.

During the study, 210 students attended the workshop and 118 paired surveys were included in the analysis. There were statistically significant improvements in all items (Table 2), with the largest improvements on the following items: Q2— “I feel I know enough about the causes of drug problems to carry out my role when working with drug users” (1.8 increase), Q6— “I feel I know how to counsel drug users over the long-term” (2.1 increase), Q7— “I feel I can appropriately advise my patients/clients about drugs and their effects” (1.7 increase), and Q10— “If I felt the need when working with drug users I could easily find someone with whom I could discuss any personal difficulties that I might encounter” (1.5 increase).

This study finds that teaching SUD as a treatable, medical disease is associated with improvements in self-reported knowledge, skills and attitudes in FM clerkship medical students, and that a short intervention can be associated with positive change. The curriculum focuses on patient-centered, destigmatized, primary care treatment that may explain the distinct improvements in questions 2, 6, 7, and 10. These improvements may help decrease treatment gaps as students form their professional identities and enter practice.

Observing high-quality patient care from family physicians treating SUDs and interacting with patients during the FM clerkship may also have changed these reported attitudes, though practice styles vary greatly in clerkship sites. Repeating this study with a larger control group would help elucidate if there is additional positive change associated with attending the workshop, versus completing the clerkship alone.

This study included only one institution’s FM curriculum and is thus limited in generalizability, but the intervention can be adopted by other programs. Our student demographics may not reflect other populations, so further studies are needed. Although not part of this study, follow-up surveys later in training would assist in learning if these changes persist. Additionally, as we did not test for knowledge gain and measured self-reported perceptions, measuring knowledge specifically may improve understanding of these interventions. More work should be done to continue to understand the most optimal training for SUDs to reduce barriers for the future medical workforce.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: This work was briefly presented at the 2020 Society of Teachers of Family Medicine, Medical Student Education Conference, as part of the General Session entitled “Equity for Addictions Starts with Students.”

References

- Lipari RN, Van Horn SL. Trends in Substance Use Disorders Among Adults Aged 18 or Older. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/report_2790/ShortReport-2790.html. Accessed August 26, 2020.

- McCance-Katz, EF. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health: 2018. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/Assistant-Secretary-nsduh2018_presentation.pdf. Accessed August 26, 2020.

- Ahmad FB RL, Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. National Center for Health Statistics. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm. Accessed August 26, 2020.

- Van Boekel LC, Brouwers EPM, Van Weeghel J, Garretsen HFL. Stigma among health professionals with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: a systemic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):23-35. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018

- Silins E, Conigrave KM, Rakvin C, Dobbins T, Curry K. The influence of structured education and clinical experience on the attitudes of medical students towards substance misusers. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26(2):191-200. doi:10.1080/09595230601184661

- Koyi MB, Nelliot A, MacKinnon D, et al. Change in medical student attitudes toward patients with substance use disorders after course exposure. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(2):283-287. doi:10.1007/s40596-017-0702-8

- Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1504-1510. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2441-1

- Miller NS, Sheppard LM, Colenda CC, Magen J. Why physicians are unprepared to treat patients who have alcohol- and drug-related disorders. Acad Med. 2001;76(5):410-418. doi:10.1097/00001888-200105000-00007

- Motzkus C, Wells RJ, Wang X, et al. Pre-clinical medical student reflections on implicit bias: implications for learning and teaching. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0225058. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0225058

- Polydorou S, Gunderson EW, Levin FR. Training physicians to treat substance use disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008;10(5):399-404.

- Cape G, Hannah A, Sellman D. A longitudinal evaluation of medical student knowledge, skills and attitudes to alcohol and drugs. Addiction. 2006;101(6):841-849. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01476.x

- Ram A, Chisolm MS. The time is now: improving substance abuse training in medical schools. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(3):454-460. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0314-0

- Muzyk A, Smothers ZPW, Akrobetu D, et al. Substance Use Disorder Education in Medical Schools: A Scoping Review. Acad Med. 2019;94(11):1825-1834.

- Walters ST, Matson SA, Baer JS, Ziedonis DM. Effectiveness of workshop training for psychosocial addiction treatments: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;29(4):283-293. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2005.08.006

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Higgins PS, Gassman RA, Gould BE. Training medical providers to conduct alcohol screening and brief interventions. Subst Abus. 2004;25(1):17-26. doi:10.1300/J465v25n01_04

- Baer JS, Rosengren DB, Dunn CW, Wells EA, Ogle RL, Hartzler B. An evaluation of workshop training in motivational interviewing for addiction and mental health clinicians. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;73(1):99-106. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.10.001

- Lewis DC. Medical education for alcohol and other drug abuse in the United States. CMAJ. 1990;143(10):1091-1096.

- Feeley RJ, Moore DT, Wilkins K, Fuehrlein B. A focused addiction curriculum and its impact on student knowledge, attitudes, and confidence in the treatment of patients with substance use. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(2):304-308.

- OHSU School of Medicine welcomes MD class of 2019. August 12, 2015. https://news.ohsu.edu/2015/08/12/ohsu-school-of-medicine-welcomes-m-d-class-of-2019#:~:text=The%20event%20will%20take%20place,and%20various%20other%20notable%20areas. Accessed Sept 12, 2020.

- Chappel JN, Veach TL, Krug RS. The substance abuse attitude survey: an instrument for measuring attitudes. J Stud Alcohol. 1985;46(1):48-52. doi:10.15288/jsa.1985.46.48

- Goodstadt MS, Cook G, Magid S, Gruson V. The Drug Attitudes Scale (DAS): its development and evaluation. Int J Addict. 1978;13(8):1307-1317. doi:10.3109/10826087809039344

- Watson H, Maclaren W, Kerr S. Staff attitudes towards working with drug users: development of the Drug Problems Perceptions Questionnaire. Addiction. 2007;102(2):206-215. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01686.x

There are no comments for this article.