The following guidelines were created by a task force convened by the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) and have been endorsed by the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM), the American College of Osteopathic Family Physicians (ACOFP), the Association of Departments of Family Medicine (ADFM), the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors (AFMRD), NAPCRG, and STFM.

SPECIAL ARTICLES

Joint Guidelines for Protected Nonclinical Time for Faculty in Family Medicine Residency Programs

Simon Griesbach, MD | Mary Theobald, MBA | Karyn Kolman, MD | Kim Stutzman, MD | Sarah Holder, DO | Michelle A. Roett, MD, MPH, CPE | Louanne Friend, PhD, MN, RN | Glenn V. Dregansky, DO | Winfred Frazier, MD, MPH | Gregory R. Lewis, MD

Fam Med. 2021;53(6):443-452.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2021.506206

Background and Objectives: Family medicine faculty face increasing expectations for clinical productivity. These expectations impinge on academic and education time and make it difficult to pursue research or scholarly activities. A task force convened by the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine created national guidelines to protect nonclinical time for family medicine faculty.

Methods: The task force reviewed existing guidelines for protected time, as well as data on current and past distribution of time for faculty in academic medicine, including a specific look at family medicine. Based on the evidence and expert opinion from task force members and leaders of family medicine organizations, the task force developed eight consensus recommendations.

Results: The guidelines include recommendations for allocation of protected time for program directors, associate program directors, and core faculty. These represent best practices to ensure programs have appropriate time to devote to the nonclinical duties of training and educating residents, while also promoting innovation in education, faculty well-being, and faculty retention.

discussion: Faculty require nonclinical time for resident development, curriculum creation and maintenance, program assessment, and scholarship. Without these functions, programs can’t meet accreditation requirements or fulfill their responsibility to develop strong family physicians. Residency programs, sponsoring institutions, universities, health care systems, and accrediting bodies should use these recommendations to develop budgets that provide appropriate time allocation to enhance faculty wellness, reduce turnover, and meet organizational missions and objectives around education and providing care for communities.

Family medicine faculty are a foundational element of graduate medical education.1 In addition to clinical and supervisory responsibilities, family medicine faculty create and maintain curricula, screen and interview residency candidates, design and deliver the majority of didactic lectures to their residents, provide evaluation and feedback to residents, and coach and mentor learners, including medical students.

Family medicine faculty are facing increasing expectations for clinical productivity, likely a product of health systems under pressure to address shrinking operating margins and declining physician clinical productivity.2,3 A 2018 survey of STFM members identified workload/administrative burden/competing priorities as members’ biggest challenge.4,5 Survey respondents noted expanding clinical demands were impinging on academic and education time, making it difficult to do research or to pursue scholarly activities required for accreditation. Faculty indicated they were overwhelmed, trying to meet administrative and clinical demands, resulting in inadequate time to teach, maintain their own knowledge, and to engage in faculty development.4,5

These responses point to both exhaustion and inefficacy—two major elements of burnout. Burnout among health care professionals has been associated with a decrease in the quality of patient care,6-8 an increase in the number of medical errors,9,10 and an increase in the risk of suicidal ideation, depression, and substance abuse.6,11,12 Family medicine consistently ranks within the top six specialties with regard to rates of reported burnout.13-15 Family medicine faculty who are unable to care for themselves cannot model and teach behaviors and strategies associated with well-being.16 Physician well-being and satisfaction have been associated with greater patient satisfaction. Academic medical centers often underestimate the cost and repercussions of faculty turnover in their organizations.17

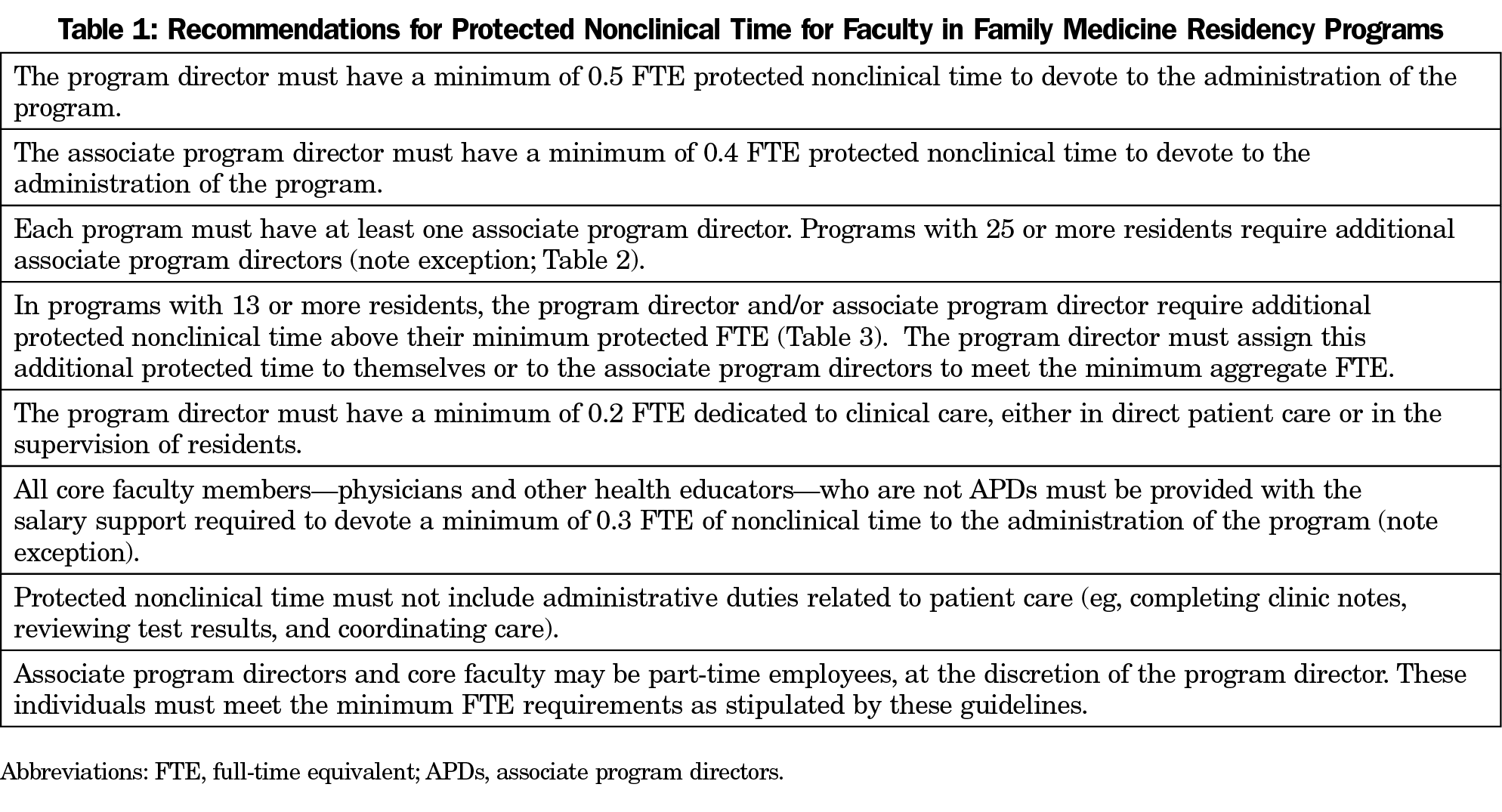

To address members’ need for an increase in protected nonclinical time and to reduce the likelihood that competing faculty priorities compromise the education of residents and/or patient care, STFM convened a task force of experts representing multiple family medicine organizations to examine the available evidence and develop national joint guidelines for protected nonclinical time for faculty in family medicine residency programs. The guidelines list recommendations for allocation of protected nonclinical time for family medicine program directors, associate program directors, and core faculty (Table 1). They are intended to represent best practices to ensure programs have appropriate time to devote to the nonclinical duties of training and educating residents, while also promoting innovation in education, faculty well-being, and faculty retention.

In developing these recommendations, the task force took into consideration the wide variety of settings and situations in which training for family medicine residents occurs. The intention was to create recommendations applicable to program leadership and faculty across all settings and in programs of all sizes.

These guidelines include recommendations for allocation of protected nonclinical time for family medicine program directors, associate program directors, and core faculty. Nonclinical time requirements for noncore faculty, residents, medical student educators, and program coordinators were not discussed. The task force considered defining time allocations based on faculty track and the unique characteristics of programs (eg, rural, newly-accredited) and ultimately agreed that program directors are best suited to adjust nonclinical time recommendations for their programs.

These guidelines should be used by family medicine residency programs, sponsoring institutions, universities, health care systems, and accrediting bodies to guide decision making about protected nonclinical time for program directors, associate program directors, and core faculty in family medicine residency programs. Specifically:

- Residency programs can use the guidelines to determine the optimal number of faculty needed, develop appropriate scheduling, and ensure the administrative duties of the program are accomplished without compromising resident education or patient care.

- Health care systems can look to these guidelines to develop budgets that provide appropriate time allocation to enhance faculty wellness, reduce turnover, and meet organizational missions and objectives around education and providing care for communities.

- Sponsoring institutions can use these guidelines to ensure the allocation of resources is appropriate to provide the program leadership and faculty the ability to create learning environments that promote patient safety, health care quality, care transitions, supervision, duty hours and fatigue management and mitigation, and professionalism.

- Accrediting bodies can look to these guidelines when creating new or revising current accreditation requirements.

In some instances, these guidelines may differ from Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requirements. Programs should ensure they meet current ACGME requirements in order to maintain accreditation.

“Total time” is the complete amount of time a faculty member works. Provided the faculty member works full time for a residency program, this typically is 1.0 full-time equivalent (FTE). This time divides into “clinical time” and “nonclinical time” (Figure 1).

"Clinical time" is time dedicated to patient care. This includes direct patient care (seeing patients without residents) with or without medical students, clinical supervision of residents (precepting), documenting/charting, answering messages from patients/clinic staff, responding to labs/tests ordered for patients, signing resident notes, and other patient care-related tasks.

“Spillover time/work after clinic” is clinical time spent during nonscheduled clinic hours. This time typically includes activities such as completing clinic notes, reviewing test results, calling/messaging patients, completing patient paperwork, and coordinating care with other team members, including specialists.

For faculty who clinically supervise residents, spillover time/work after clinic also includes time spent in clinical activities such as signing and reviewing resident clinic notes, reviewing/discussing test results, and helping residents navigate the health care system in the best interest of their patients.

“Nonclinical time” is the portion of time faculty dedicate to duties other than those related to patient care. It does not include time spent in duties classified as clinical time (eg, supervision of residents in the clinical setting) or spillover time/work after clinic.

Nonclinical time may include, but is not limited to:

- Advising, mentoring, and coaching residents (cocreating, implementing, and monitoring individualized learning plans)

- Supporting/overseeing residents in the development/assessment of innovative quality improvement/patient safety projects relevant to the population served

- Participating in educational activities (eg, didactics, lab, or simulation)

- Developing, implementing, and assessing components of the curriculum

- Designing and implementing simulation and standardized patient curricula for teaching and assessment

- Designing and overseeing remediation plans

- Supporting/overseeing residents in the conduct of their scholarly work, including the dissemination of such work through presentations, posters/abstracts, and peer-reviewed publications

- Teaching residents how to teach

- Teaching/mentoring medical students with an interest in family medicine

- Membership on the Clinical Competency Committee (CCC)

- Designing and implementing the program’s assessment strategies, ensuring there are robust methods to assess each competency, and that assessment methods provide meaningful information by which the CCC can judge resident performance on the Milestones

- Monitoring the quality of the clinical learning environment, including regular assessments of adequate clinical volume

- Serving as a representative on clinical quality committees that are external to the program

- Participating in the Annual Program Review as chair or member of the Program Evaluation Committee

- Implementing and analyzing the outcome of action plans developed by the Program Evaluation Committee

- Participating in recruitment, selection, and retention of residents and faculty

- Leading and participating in the program’s efforts related to resident and faculty well-being

- Participating in and/or overseeing faculty development activities.

“Time dedicated to the program” is the sum of time spent supervising residents in the clinical space, including the administrative work that goes with that, and nonclinical time (as defined above). It does not include time spent in direct patient care, precepting medical students, the administrative work that goes with these activities or administrative responsibilities unrelated to the faculty member’s duties to the residency program.

“Core faculty” are residency faculty who have a substantial commitment to the residency program, such that they can support program leadership in evaluating the program and its residents, and contribute to the program’s development and growth including (but not limited to) curriculum development and implementation, recruitment, and program self-assessment. Core faculty must be designated by the program director and may include physicians as well as other health educators. The associate program director (APD) is a core faculty member. The program director is not a core faculty member.

“Other health educators” are individuals who contribute to the clinical and/or didactic learning of residents and are not physicians. Examples of other health educators include behavioral health specialists, pharmacists, nutritionists, PhDs, and social workers.

“Part-time faculty” are individuals who work fewer than 1.0 FTE (100% full-time equivalent) in the program and/or institution. Faculty with multiple employers who work a combined total 1.0 FTE, with <1.0 FTE at the residency program and/or institution should be considered part-time faculty.

Task Force Selection

Protected Faculty Time Task Force members were selected through an open call for applications and personal invitations, with the intent to bring together diversity in role, geography, residency size and structure, race and ethnicity, age, experience, and gender.

Review of Existing Guidelines

Task force members first reviewed existing guidelines for protected faculty time. The AAFP Residency Program Solutions (RPS) publishes Criteria for Excellence, a highly-regarded collection of consensus-based best practices for family medicine graduate medical education programs.18 The task force also reviewed guidance the ACGME formerly provided to designated institutional officials with specified minimum time allocations for faculty and program directors based on specialty-specific review committee recommendations prior to 2019.19,20

Literature Search Strategy

The task force conducted a literature review. They performed a search of PubMed database with the terms [“protected academic faculty time” OR “protected administrative faculty time” OR “protected non-clinical time”]. Over 1,000 results were returned and abstracts read for relevance. The task force reviewed the bibliography of relevant publications to identify additional helpful articles.

Additional relevant materials included:

- Results of an STFM survey of family medicine program directors;

- Results of an STFM member survey;

- Data from the University of Washington WWAMI Region Family Medicine Residency Network, where investigators of a study asked program directors to estimate the amount of clinical time family medicine faculty spent performing various activities; and

- ACGME’s current Data Resource Book and its published archives of faculty characteristics as reported in the ACGME’s Accreditation Data System (ADS).

The task force collected and utilized these materials to form the basis of consensus guidelines.

Identification of Guideline Statements and Development of Consensus

After reviewing relevant literature, task force members individually developed recommendations for statements pertaining to program director, associate program director, and faculty nonclinical time, as well as other pertinent recommendations. At a meeting, each guideline statement was vetted by the panel of experts on the Protected Faculty Time Task Force. Statements underwent successive edits until the panel reached a consensus about each statement’s relevance and applicability to the task force’s specified scope. The task force approved the final collection of statements. The task force discussed use of levels of evidence and agreed that given the limited amount of rigorous, peer-reviewed evidence, final recommendation statements would not include levels of evidence.

External Review

After completing its draft guidelines and supporting statements, the task force submitted them for review to the STFM Board of Directors and a reactor panel comprised of experienced family medicine faculty representing a broad range of roles, geographic locations, and practice settings. After further edits, the task force submitted the guidelines to the Family Medicine Leadership Consortium (leaders of the AAFP, the AAFP Foundation, ABFM, ACOFP, ADFM, AFMRD, NAPCRG, and STFM) for review and comment. After final revisions, the guidelines were sent to supporting organizations for endorsement.

Recommendation 1: The Program Director Must Have a Minimum of 0.5 FTE Protected Nonclinical Time to Devote to the Administration of the Program

From 2007-2019, family medicine program directors reported to the ACGME an average of 0.6 FTE spent on nonclinical activities. This has trended downward slightly over time, from 0.7 FTE in 2007.21 The most recent edition of RPS Criteria for Excellence recommends a similar range of protected nonclinical time for program directors, between 0.5 and 0.8 FTE. The RPS Criteria for Excellence authors highlight the need for protected nonclinical time and discuss the opportunity to share administrative responsibilities with associate program director(s).18 While other specialties’ ACGME requirements for program directors designate varied levels of required time for nonclinical work, many primary care specialties, such as pediatrics and internal medicine, require a minimum of 0.5 FTE.19 Additionally, in emergency medicine, orthopedics, and cardiology, program directors report devoting a larger portion of their time for administrative duties that focused on research.18,19,22-25 Having more protected nonclinical time should allow for a larger amount of program director-driven educational research.

Program director turnover is a significant challenge facing family medicine residency training programs. Median tenure for program directors in ACGME-accredited family medicine residency programs is 4.5 years.26 Program directors report challenges including administrative duties, clinical load, family obligations, teaching responsibilities, and research demands. Departing program directors report “a sense of building exhaustion, burnout, or burden of too much work as a factor in their decisions to step away.”27 Sixty-nine percent of departing program directors with fewer than 6 years of tenure cite “there was no room for other pursuits (eg, research, other scholarly work)” as a factor in their departure.27

As residency programs continue to innovate and the complexity of ACGME requirements continues to grow, the need for protected time to appropriately adjust to these changes is crucial. For example, 3 years after the implementation of core competencies, nearly 20% of program directors were unaware that failure to evaluate competencies could result in citation.23 Program directors reported insufficient time and insufficient faculty development as the major barriers to implementation.23 Appropriate allocation of protected nonclinical time provides the program director time to fully address changes in regulatory requirements, adapt current processes to accommodate them, and train the faculty in their implementation.

Recommendation 2: The Associate Program Director Must Have a Minimum of 0.4 FTE Protected Nonclinical Time to Devote to the Administration of the Program.

As part of the leadership team, associate program directors (APDs) assist with program administration and clinical education.1 Common activities include general administration, counseling/advising residents, teaching, recruitment, and curriculum development. Less common activities are evaluation/assessment, faculty development, providing feedback to trainees, research, and career advancement planning.28,29 The responsibilities of this position require protected nonclinical time.

In a 2013 survey, pediatric APDs reported they were compensated at <0.25 FTE (34-36%), 0.25 to 0.5 FTE (60-62%), and >0.5 FTE (2-5%) for their APD role.29 Despite allocation of protected time, their top three concerns about their position were:

(1) lack of time (ie, clinical responsibilities conflicted with residency time); (2) faculty engagement (ie, difficulty engaging faculty in teaching, evaluation, and other educational missions); and (3) scholarly work (ie, insufficient time and resources for projects, research, and promotion).29

This is consistent with the STFM survey, where members identified workload/administrative burden/competing priorities as members’ biggest challenge.4

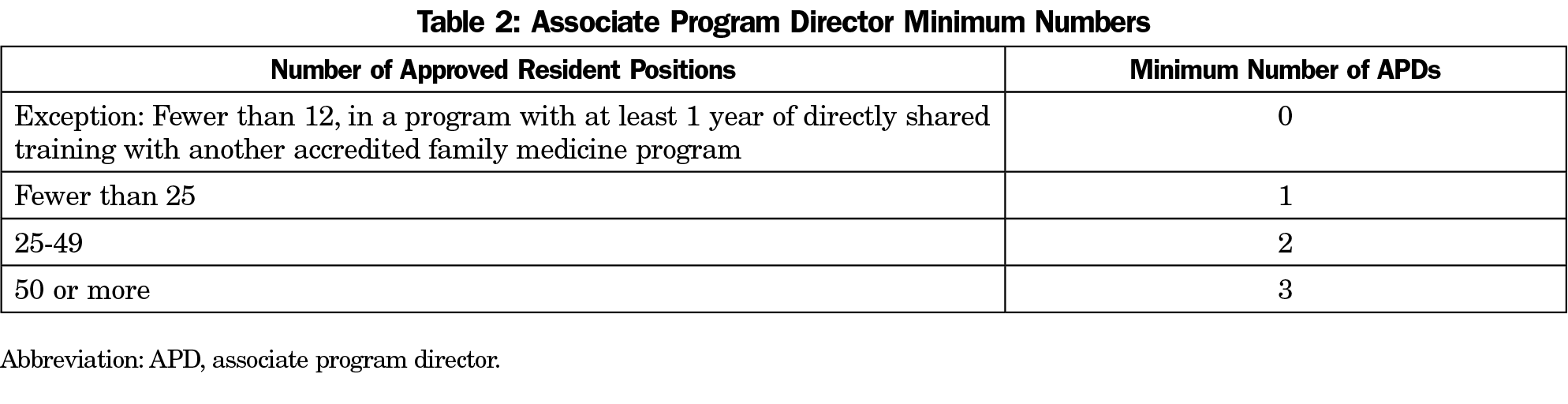

Recommendation 3: Each Program Must Have at Least One Associate Program Director. Programs With 25 or More Residents Require Additional Associate Program Directors (Note Exception; See Table 2).

Though much nonclinical work at a program is independent of program size, the volume of some work, such as interviewing, advising, evaluating, and remediating residents, increases as the number of residents within the program increases. The responsibilities associated with administration and leadership of small programs can be shared between a program director and an APD. Larger programs presumably require additional APDs to share in the increasing administrative responsibilities.

An exception to this recommendation is very small programs (fewer than 12 residents), in which trainees have at least 1 year of directly shared training with another accredited family medicine program.

In the absence of data suggesting an ideal ratio of residents to APDs, the task force recommends the designations shown in Table 2.

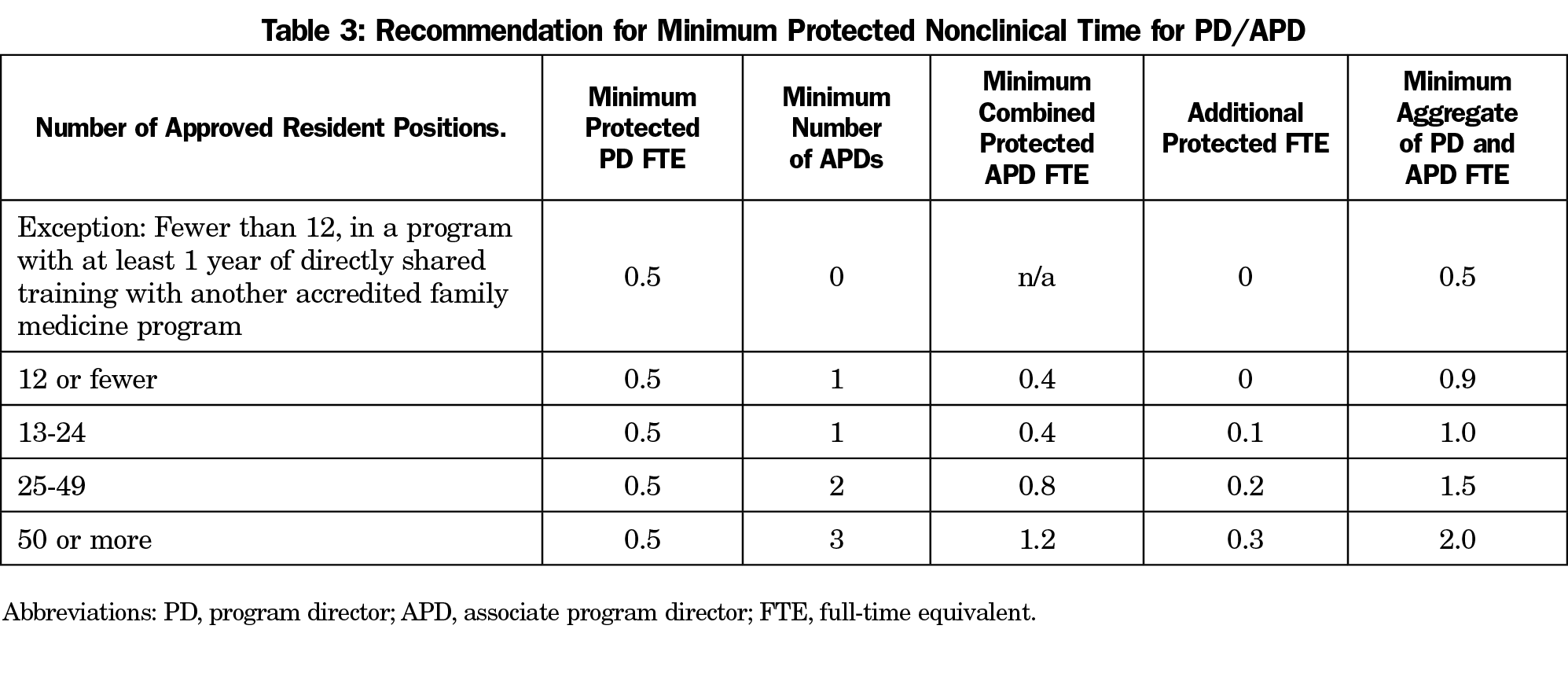

Recommendation 4: In Programs With 13 or More Residents, the Program Director and/or Associate Program Director Require Additional Protected Nonclinical Time Above Their Minimum Protected FTE (Table 3). The Program Director Must Assign This Additional Protected Time to Themselves or to the Associate Program Directors to Meet the Minimum Aggregate FTE.

Large programs with more residents have a higher volume of administrative work that can be accomplished by either adding APDs or protecting additional time.

The ACGME does not define the role of the APD as clearly as it defines the role of the program director. As a result, APDs’ roles vary significantly between institutions. Data from ACGME ADS reflect a gradual decrease in program director time spent in administrative duty, from approximately 70% in 2007 to approximately 60% in 2019.21 This may be due to increased time constraints faced by program directors, but may also reflect increased delegation of responsibilities to core faculty and/or APDs. The Residency Program Solutions Criteria for Excellence suggests that there should be a range of protected time for program directors that takes into account associate program directors’ protected administrative time.18 The 2019 ACGME Common Program Requirements reflect an intent to “provide greater flexibility within an established framework, allowing programs and residents more discretion to structure clinical education in a way that best supports … principles of professional development.”30

Data from a 2018 WWAMI Region Family Medicine Residency Network survey of 26 family medicine residency programs indicate that their median FTE for program director and APD nonclinical time is 0.57.31

Administrative pressures contribute to the 12%-14% program director turnover per year in family medicine and median program director tenure of 4-5 years.26,32 Allowing program directors the flexibility to share nonclinical responsibilities may reduce burnout. The task force concluded that provision of additional protected nonclinical time program directors can assign to themselves or distribute to their associate program directors is needed to complete the additional work encountered in residency programs with a greater number of residents (Table 3).

Recommendation 5: The Program Director Must Have a Minimum of 0.2 FTE Dedicated to Clinical Care, Either in Direct Patient Care or in the Supervision of Residents.

In order to remain clinically relevant and maintain role-modeling and mentorship, program directors must provide direct patient care and precept their residents.18,30 In its most recent Common Program Requirements, the ACGME describes the program director as a “role model [who] must participate in clinical activity consistent with the specialty.30 The task force agreed, concluding that program directors must dedicate a minimum of 0.2 FTE to clinical care.

Recommendation 6: All Core Faculty Members—Physicians and Other Health Educators— Who Are Not APDs Must Be Provided With the Salary Support Required to Devote a Minimum of 0.3 FTE of Nonclinical Time to the Administration of the Program (Note Exception).

The ABFM conducted a study of family medicine program directors in July 2020, showing the effects of the July 2019 change in ACGME program requirements that removed the requirement that core physician faculty dedicate “at least 60% time (at least 24 hours per week, or 1,200 hours per year), to the program, exclusive of patient care without residents.” The survey results showed at least 75% experienced significant adverse impact, with 69.9% reporting “immediate and direct changes” on their budgets and faculty time allocations. Program directors noted direct reductions of faculty time for education and clinical supervision of residents, pressure to generate more visits, and significant impact on morale and quality of education. An additional 9% of program directors reported that they feel changes are imminent.33

Core faculty (physicians and other health educators) must participate in a wide range of clinical and nonclinical activities in order to ensure the success of family medicine training programs and comply with requirements set forth by the ACGME. A minimum of 0.3 FTE is in line with results of several surveys about time spent by core faculty in nonclinical activities. A 2018 survey of 26 programs in the WWAMI Region Family Medicine Residency Network, indicated core faculty are allocated 24% of their time to administration of the program. This includes 0% of their time allocated to scholarship.31 Another survey of 58 family medicine program directors from across the United States reported that core faculty, both physicians and other health educators, were allocated an average of 26% FTE protected nonclinical time.34 ACGME ADS data from 2010 to 2019 show that faculty spent between 16% and 26% of their total time as nonclinical time.21 A recommendation of 0.3 FTE also aligns closely with the RPS Criteria for Excellence recommendations. They recommend, with a 1:4 faculty to resident ratio, that core faculty spend at least 25% FTE in protected nonclinical time.18 Giving consideration to the range of protected nonclinical time allocations and recommendations present in the literature, the task force concluded that faculty require a minimum of 0.3 FTE protected nonclinical time.

An exception to this recommendation is new programs (those that haven’t yet graduated their first class of residents) or very small programs, where program directors may need more flexibility to accomplish the clinical requirements of the program.

Recommendation 7: Protected Nonclinical Time Must Not Include Administrative Duties Related to Patient Care (eg, Completing Clinic Notes, Reviewing Test Results, and Coordinating Care).

Many clinical teachers do not feel they have sufficient time to teach.35,36 Competing time demands and lack of support for scientific work are a top reason why academic faculty leave practice.37 A 2014 cross-sectional study of US physician work hour distribution revealed that family physicians, most of whom did not appear to work in academic settings, spent approximately 8 hours—or 17% of their time—doing administrative work.38 Studies examining both outpatient39,40 and inpatient41 time use note similar amounts of administrative work stemming from direct patient care or resident supervision. Based on this, the task force recommends health systems and residency programs should distinguish administrative clinical duties (also called spillover work or work after clinic) separately from administration of residency programs and provide adequate time for the performance of both duties.

Recommendation 8: Associate Program Directors and Core Faculty May Be Part-Time Employees, at the Discretion of the Program Director. These Individuals Must Meet the Minimum FTE Requirements as Stipulated by These Guidelines

Part-time faculty demonstrate similar clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction levels to their full-time colleagues,42-46 and primary care department chairs generally approve of faculty choosing to work part-time. Chairs note financial benefits for departments and the opportunity to keep “talented people in the workforce who might otherwise leave.”47 Based on this limited available information, the task force concluded that, at the discretion of the program director, associate program directors and core faculty could be part-time employees.

Organizations within emergency medicine and internal medicine, in addition to family medicine, have released statements emphasizing the importance of protected nonclinical time.48,49 However, much of the literature on this topic describes the amount of time rather than comparison of outcomes related to changes in or allocation of nonclinical time. A future research approach focused on family medicine is vital. There are a number of areas that should be explored in order to guide future recommendations, including those described in the sections following.

Gaps in Current Literature

During creation of this guideline, the task force noted a paucity of literature examining optimal amounts of protected time within the specialty of family medicine. Given the wide variety of nonclinical time allocations among residency programs, future work should focus on a scholarly approach to determination of an optimal amount of protected time for different faculty roles. Measurement of outcomes, such as scholarly productivity, learner satisfaction, educator satisfaction, department chair/program director satisfaction, and patient satisfaction, may aid in this determination. Ideally, organizations with different amounts of protected nonclinical time for their faculty could aggregate and publish their experiences to help quantify the most effective allocation of nonclinical time and faculty-to-resident ratio.

Other health educators within the definition of core faculty have largely unknown protected time designations, and their roles and responsibilities may vary greatly based on their professions and roles within a residency program. Further work could explore whether these other health educator faculty should have the same protected-time allocations as physician faculty and/or if the need varies by profession.

In reviewing the literature, the task force noted wide differences in protected nonclinical time between medical specialties, as well as between individual programs. In the future, investigators detailing the practices of medical specialties and residency programs that demonstrate more nonclinical productivity or efficiency with lesser amounts of protected nonclinical time could determine best practices that would improve efficient utilization of nonclinical time and inform future faculty development. Similarly, evaluation of the relationship between the amount and complexity of ACGME requirements and protected nonclinical time would be helpful in assessing whether protected time need correlates with the level of regulation.

The task force identified a need for additional research into the optimal faculty-to-resident ratio. Authors of an Annals of Emergency Medicine article recommended varying faculty responsibilities and increasing the number of faculty to address the clinical, research, and teaching demands faced by faculty in residency programs.50 The Residency Program Solutions Criteria for Excellence recommends a core faculty-to-resident ratio between 1:3 and 1:4, depending on program size.18 A recent survey of the residency programs in the WWAMI Region Family Medicine Residency Network showed that the 26 programs, which have on average 23 residents, have approximately a 1:3 faculty to resident ratio.31 Other specialties appear to be exploring a similar means of calculating an ideal number of faculty within their program.

Evaluating Impact of Protected Nonclinical Time Guidelines

One of the goals of these recommendations is to reduce the growing problem of academic faculty burnout.51 Lack of protected nonclinical time is a common reason faculty leave academic medicine.37,52 We recommend examining how implementation of these guidelines or other changes in non-clinical time impact faculty burnout and well-being.

Additionally, although family medicine research and scholarly activity has increased over time, a recent study showed only 15% of family medicine faculty publish their research.53 We suggest evaluating how increases or decreases in protected nonclinical time allocation affect faculty research productivity subsequent to the change.

During development of the guidelines, the task force considered whether protected time allocations could have unintended consequences on programs, such as reductions in faculty pay, limits on the number of faculty designated as core for ACGME purposes, and/or challenges with time allocations for part-time faculty. While it was beyond the scope of the task force’s work to examine how institutions are funding or should fund high-quality graduate medical education, the financial impact of implementation of the guidelines, including any reallocation of resources, should be part of return-on-investment calculations.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: The task force that created these guidelines received staff support and funding for travel from the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The majority of this article’s authors work in family medicine residency programs, and therefore would be impacted by implementation of these guidelines.

Presentations: These recommendations were presented at the AAFP Residency Leadership Summit in March 2021.

References

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/120_FamilyMedicine_2019.pdf?ver=2019-06-13-073936-407. Published online June 9, 2019. Accessed July 5, 2019.

- Lapointe J. Health System Operating Margins Improve, But Still Below 2015 Level. RevCycleIntelligence. https://revcycleintelligence.com/news/health-system-operating-margins-improve-but-still-below-2015-level. Published October 29, 2019. Accessed October 29, 2020.

- Morris S, Lusby H. The Physician Compensation Bubble Is Looming. American Association for Physician Leadership. https://www.physicianleaders.org/news/physician-compensation-bubble-looming. Published January 16, 2019. Accessed October 29, 2020.

- Theobald M. STFM advocates for protected nonclinical time for residency faculty. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(5):467-468. doi:10.1370/afm.2455

- Theobald M. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine 2018 Member Survey [Unpublished raw data].

- Shirom A, Nirel N, Vinokur AD. Overload, autonomy, and burnout as predictors of physicians’ quality of care. J Occup Health Psychol. 2006;11(4):328-342. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.11.4.328

- Weigl M, Schneider A, Hoffmann F, Angerer P. Work stress, burnout, and perceived quality of care: a cross-sectional study among hospital pediatricians. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174(9):1237-1246. doi:10.1007/s00431-015-2529-1

- Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Trojanowski L. The relationship between physician burnout and quality of healthcare in terms of safety and acceptability: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e015141. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015141

- Wen J, Cheng Y, Hu X, Yuan P, Hao T, Shi Y. Workload, burnout, and medical mistakes among physicians in China: A cross-sectional study. Biosci Trends. 2016;10(1):27-33. doi:10.5582/bst.2015.01175

- Hayashino Y, Utsugi-Ozaki M, Feldman MD, Fukuhara S. Hope modified the association between distress and incidence of self-perceived medical errors among practicing physicians: prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35585. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035585

- Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(5):334-341. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-451. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134

- Peckham C. Medscape National Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2018. Medscape. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2018-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6009235. Published January 17, 2018. Accessed March 22, 2021.

- Kane L. Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2020: The Generational Divide. Medscape. www.medscape.com/slideshow/2020-lifestyle-burnout-6012460. Published January 15, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2021

- Kane L. Medscape National Physician Burnout, Depression & Suicide Report 2019. Medscape. www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056. Published January 16, 2019. Accessed March 22, 2021.

- Bohman B, Dyrbye L, Sinsky CA, et al. Physician well-being: the reciprocity of practice efficiency, culture of wellness, and personal resilience. NEJM Catal. 2017;3(4):4.

- Shanafelt T, Goh J, Sinsky C. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1826-1832. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4340

- Blake G, Crane S, Fahrenwald R, et al. Criteria for Excellence. 11th ed. Leawood, KS: American Academy of Family Physicians; 2019.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Specialty-specific References for DIOs: Expected Time for Program Director. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Specialty-specific%20Requirement%20Topics/DIO-Expected_Time_PD.pdf. Published online June 2018. Accessed July 5, 2019.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Specialty-specific References for DIOs: Expected Time for Faculty. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Specialty-specific%20Requirement%20Topics/DIO-Expected_Time_Faculty.pdf. Published online June 2018. Accessed July 5, 2019.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Appendix 1. 2007-2019 ADS Data on Time. https://www.acgme.org/About-Us/Publications-and-Resources/Graduate-Medical-Education-Data-Resource-Book. Published online 2019. Accessed October 8, 2019.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book Academic Year 2018-2019. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/PublicationsBooks/2018-2019_ACGME_DATABOOK_DOCUMENT.pdf?ver=2019-09-30-114537-793. Published online 2019. Accessed October 8, 2019.

- Delzell JE Jr, Ringdahl EN, Kruse RL. The ACGME core competencies: a national survey of family medicine program directors. Fam Med. 2005;37(8):576-580.

- Beeson MS, Gerson LW, Weigand JV, Jwayyed S, Kuhn GJ. Characteristics of emergency medicine program directors. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(2):166-172. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2005.08.010

- Sanders AB, Spaite DW, Smith R, Criss E. Allocation of time in three academic specialties. J Emerg Med. 1988;6(5):435-437. doi:10.1016/0736-4679(88)90025-X

- Brown SR, Gerkin R. Family Medicine Program Director Tenure: 2011 Through 2017. Fam Med. 2019;51(4):344-347. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.730498

- Fernald DH, Van Auken K, Hester C, Brown SR. Why family medicine program directors leave their position: results from an AFMRD tenure study. Fam Med. Forthcoming 2021.

- Amersi F, Choi J, Molkara A, Takanishi D, Deveney K, Tillou A. Associate Program Directors in Surgery: A Select Group of Surgical Educators. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(2):286-293. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.08.014

- Narayan AP, McPhillips HA, Anderson MS, et al. Strengthening the associate program director workforce: needs assessment and recommendations. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(4):332-334. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2014.05.003

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2019.pdf. Published online June 10, 2018. Accessed July 5, 2019.

- University of Washington WWAMI Region Family Medicine Residency Network 2019 Program Directors Survey [unpublished raw data].

- Mitchell K, Maxwell L, Bhuyan N, et al. Program director turnover. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(5):482-483. doi:10.1370/afm.1703

- Newton W, Magill M. The Impact of the ACGME’s June 2019 Changes in Residency Requirement. Forthcoming 2021.

- Jarrett J, Griesbach S, Theobald M, et al. Non-Clinical Time for Family Medicine Residency Faculty: National Survey Results. [Manuscript submitted for publication 2021].

- Schiekirka-Schwake S, Anders S, von Steinbüchel N, Becker JC, Raupach T. Facilitators of high-quality teaching in medical school: findings from a nation-wide survey among clinical teachers. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):178. doi:10.1186/s12909-017-1000-6

- Huwendiek S, Hahn EG, Tönshoff B, Nikendei C. Challenges for medical educators: results of a survey among members of the German Association for Medical Education. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2013;30(3):Doc38.

- Pereyra-Rojas M, Mu E, Gaskin J, Lingham T. The higher-ed organizational-scholar tension: how scholarship compatibility and the alignment of organizational and faculty skills, values and support affects scholars’ performance and well-being. Front Psychol. 2017;8:450. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00450

- Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU. Administrative work consumes one-sixth of U.S. physicians’ working hours and lowers their career satisfaction. Int J Health Serv. 2014;44(4):635-642. doi:10.2190/HS.44.4.a

- Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(11):753-760. doi:10.7326/M16-0961

- Young RA, Burge SK, Kumar KA, Wilson JM, Ortiz DF. A time-motion study of primary care physicians’ work in the electronic health record era. Fam Med. 2018;50(2):91-99. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.184803

- Kara A, Flanagan M, Gruber R, Kroenke K, Weiner M. A Time Motion Study Evaluating the Impact of Geographic Cohorting of Hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2019. doi:10.12788/jhm.3339

- Fairchild DG, McLoughlin KS, Gharib S, et al. Productivity, quality, and patient satisfaction: comparison of part-time and full-time primary care physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(10):663-667. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.01111.x

- Parkerton PH, Wagner EH, Smith DG, Straley HL. Effect of part-time practice on patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(9):717-724. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20401.x

- McMurray JE, Heiligers PJM, Shugerman RP, et al; Society of General Internal Medicine Career Satisfaction Study Group (CSSG). Part-time medical practice: where is it headed? Am J Med. 2005;118(1):87-92. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.11.005

- Darbar M, Emans SJ, Harris ZL, Brown NJ, Scott TA, Cooper WO. Part-time physician faculty in a pediatrics department: a study of equity in compensation and academic advancement. Acad Med. 2011;86(8):968-973. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318222317e

- Panattoni L, Stone A, Chung S, Tai-Seale M. Patients report better satisfaction with part-time primary care physicians, despite less continuity of care and access. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(3):327-333. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-3104-6

- Socolar RR, Kelman LS. Part-time faculty in academic pediatrics, medicine, family medicine, and surgery: the views of the chairs. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2(5):406-413. doi:10.1367/1539-4409(2002)0022.0.CO;2

- Greenberger SM, Finnell JT II, Chang BP, et al. Changes to the ACGME Common Program Requirements and their potential impact on emergency medicine core faculty protected time. AEM Educ Train. 2020;4(3):244-253. doi:10.1002/aet2.10421

- Fazio SB, Chheda S, Hingle S, et al. The challenges of teaching ambulatory internal medicine: faculty recruitment, retention, and development: an AAIM/SGIM position paper. Am J Med. 2017;130(1):105-110. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.09.004

- Meislin HW, Spaite DW, Valenzuela TD. Meeting the goals of academia: characteristics of emergency medicine faculty academic work styles. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21(3):298-302. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(05)80891-1

- Girod SC, Fassiotto M, Menorca R, Etzkowitz H, Wren SM. Reasons for faculty departures from an academic medical center: a survey and comparison across faculty lines. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):8. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0830-y

- Pollart SM, Novielli KD, Brubaker L, et al. Time well spent: the association between time and effort allocation and intent to leave among clinical faculty. Acad Med. 2015;90(3):365-371. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000458

- Liaw W, Petterson S, Jiang V, et al. The scholarly output of faculty in family medicine departments. Fam Med. 2019;51(2):103-111. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.536135

Lead Author

Simon Griesbach, MD

Affiliations: Waukesha Family Medicine Residency at ProHealth Care, Waukesha, WI

Co-Authors

Mary Theobald, MBA - Society of Teachers of Family Medicine, Leawood, KS

Karyn Kolman, MD - University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson

Kim Stutzman, MD - Family Medicine Residency of Idaho – Nampa

Sarah Holder, DO - AtlantiCare Family Medicine Residency Program and Geisinger Commonwealth SOM, Scranton, PA

Michelle A. Roett, MD, MPH, CPE - MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC

Louanne Friend, PhD, MN, RN - College of Community Health Science/Institute for Rural Health Research, Tuscaloosa, AL

Glenn V. Dregansky, DO - Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine

Winfred Frazier, MD, MPH - UPMC St Margaret Family Medicine Residency Program, Pittsburg, PA

Gregory R. Lewis, MD - California Hospital Medical Center Family Medicine Residency

Corresponding Author

Simon Griesbach, MD

Correspondence: Waukesha Family Medicine Residency at ProHealth Care; 210 NW Barstow, Suite 201, Waukesha, WI 53188. 262-928-5584.

Email: simon.griesbach@phci.org

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.