Background and Objectives: In the United States, 89% of counties have no clinics providing abortion care. Though training residents increases intention to provide abortion care, rates of postresidency abortion provision are low. This study, conducted at one family medicine residency program in the Southwest United States, examines graduates’ postresidency practice of abortion care in the context of their intent to provide during residency training.

Methods: We collected cross-sectional data from a survey of graduates of University of New Mexico Family Medicine Residency from 2005 to 2017. We performed a mixed-methods analysis using descriptive statistics and conceptual content analysis, including a new methodology of performing content analysis of four subgroups based on intention to provide abortion care at different time points.

Results: The response rate was 46%, with 54 responses to 115 surveys. Only 35% residents who intended to provide abortion care had done so after graduation from residency. Barrier analysis revealed that the three most frequent barriers were structural, with 52% of respondents saying that their workplace would not allow abortion care. The two most frequent themes affecting intention were “competence” and feeling that abortion care was “medically necessary.” However, the two most common themes affecting actual practice were “workplace support” and local “patient access.”

Conclusions: This study provides information about the themes associated with changing intentions and practice of abortion care, which may help elucidate new strategies for training residents to anticipate and address challenges to postresidency provision. The study also provides some insight into residents with no intention to provide abortion care in residency who develop an intention to provide abortion care after graduation, which is a group of people for whom there is little information.

In the United States, 89% of counties have no clinics providing abortion care.1 Family medicine and Ob-Gyn program graduates who participated in abortion training have low rates of providing abortion care after graduation.2-4 Previous studies analyzed barriers that contribute to low rates of abortion care provision.5-7

This study, conducted at one family medicine residency program in the Southwest United States, was designed to examine the graduates’ postresidency practice of abortion care in the context of their intent to provide during residency training. The study asked why graduates of the University of New Mexico Family Medicine Residency (UNMFMR) made the decision to provide (or not provide) abortion care. UNMFMR offers opt-out abortion training and is a Reproductive Health Education in Family Medicine (RHEDI) program. This analysis may help elucidate strategies to enhance training to better support postresidency abortion provision.

The study population was graduates of UNMFMR from 2005 to 2017. In 2018, we sent a 10-minute survey of 23 questions, developed after literature review, via REDCap.8,9 The survey included quantitative questions about postgraduation abortion practice, barriers experienced, and intention to provide abortion care at two time points, and two open-ended questions about the decision to provide abortion care. The University of New Mexico Human Research Review Committee approved this study as exempt.

We used STATA v 14.0 for descriptive statistics, including frequencies of common barriers to abortion provision. We used Microsoft Office 365 for a conceptual content analysis, which involved the authors collaboratively inductively identifying concepts and counting the frequency of those concepts. By arranging graduates into subgroups based on their intention to provide abortion care at two key time points, we organized the themes with changing intention as the key characteristic to examine.10-12

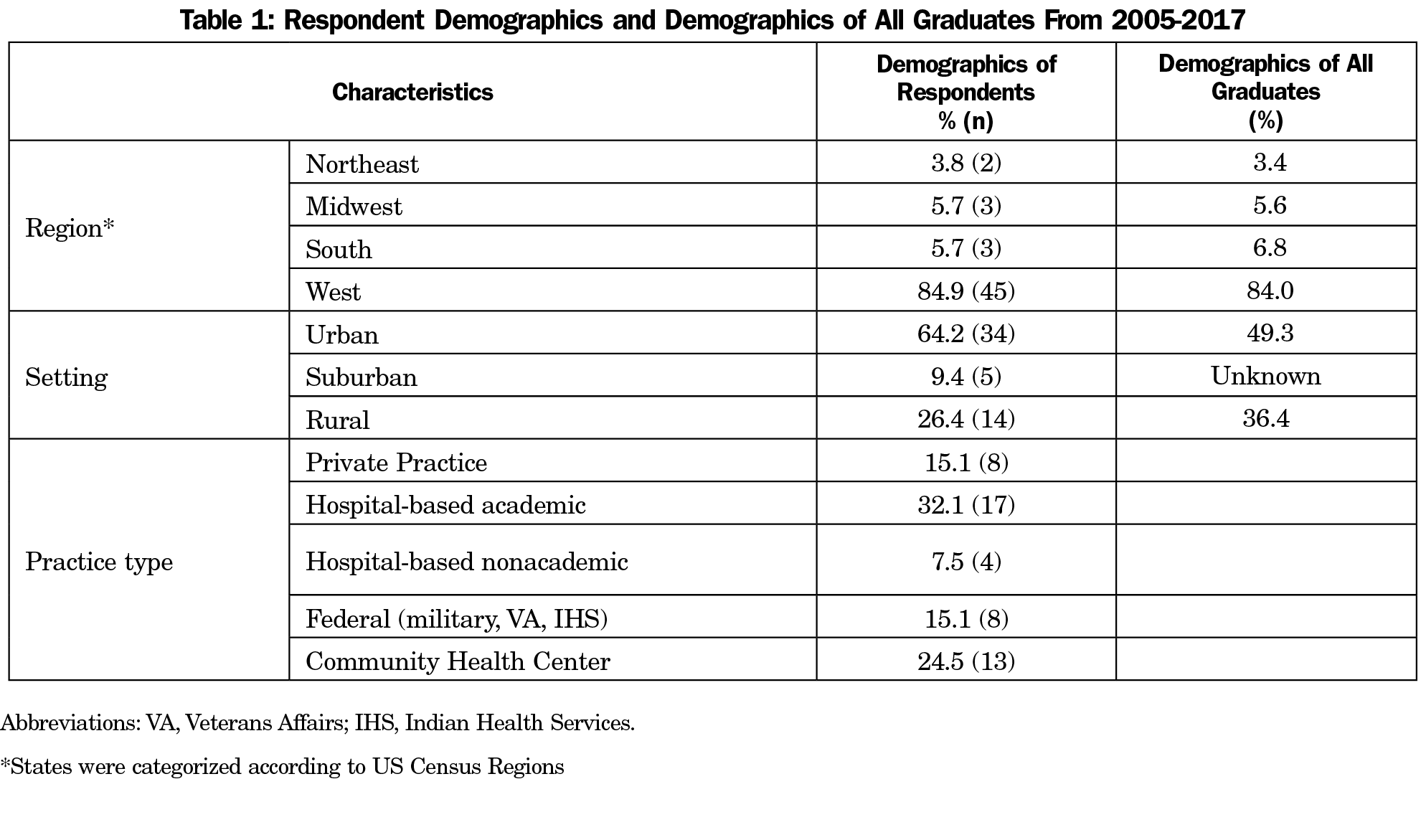

For the 142 graduates in our time frame, 115 had known and functional email addresses. The response rate was 46%, with 54 survey responses. In Table 1, the geographic distribution of survey respondents is similar to that of all graduates from 2005 to 2017. The majority of respondents (64%) worked in an urban practice setting, which is greater than the percentage of total program graduates who work in an urban setting (49%). There were no data for all graduates’ practice type.

Descriptive Statistics

Forty-five respondents (87%) participated in integrated abortion training. Of trained residents, 17 (39%) intended to provide abortion care after graduation. Of that subset with intention, six graduates (35%) had provided medical abortion care after residency, and three (18%) had provided procedural abortion care.

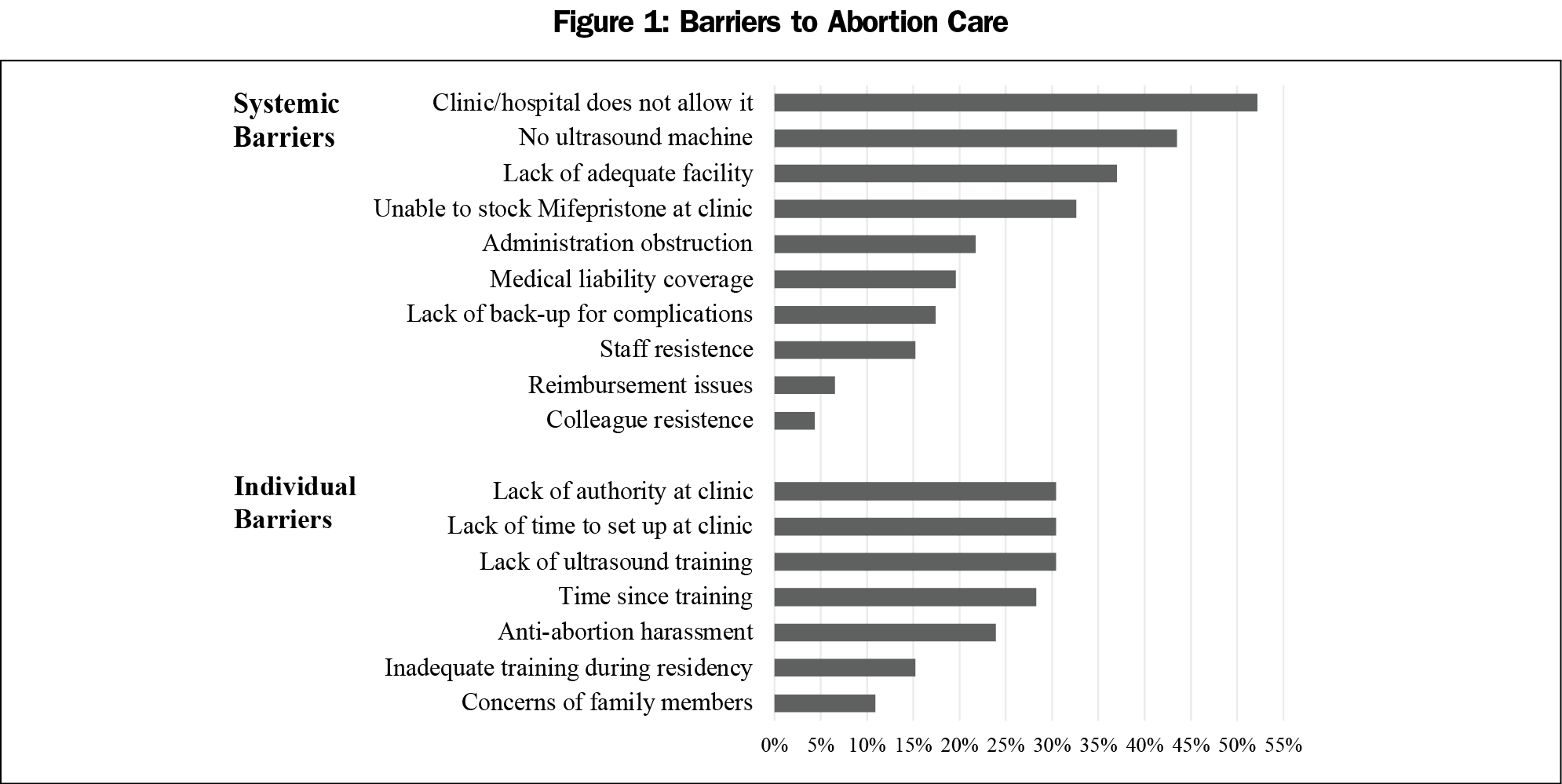

For all survey respondents, Figure 1 shows that the most common barriers were workplaces not allowing abortion care (52%) and not having ultrasound machines (43%).

Content Analysis

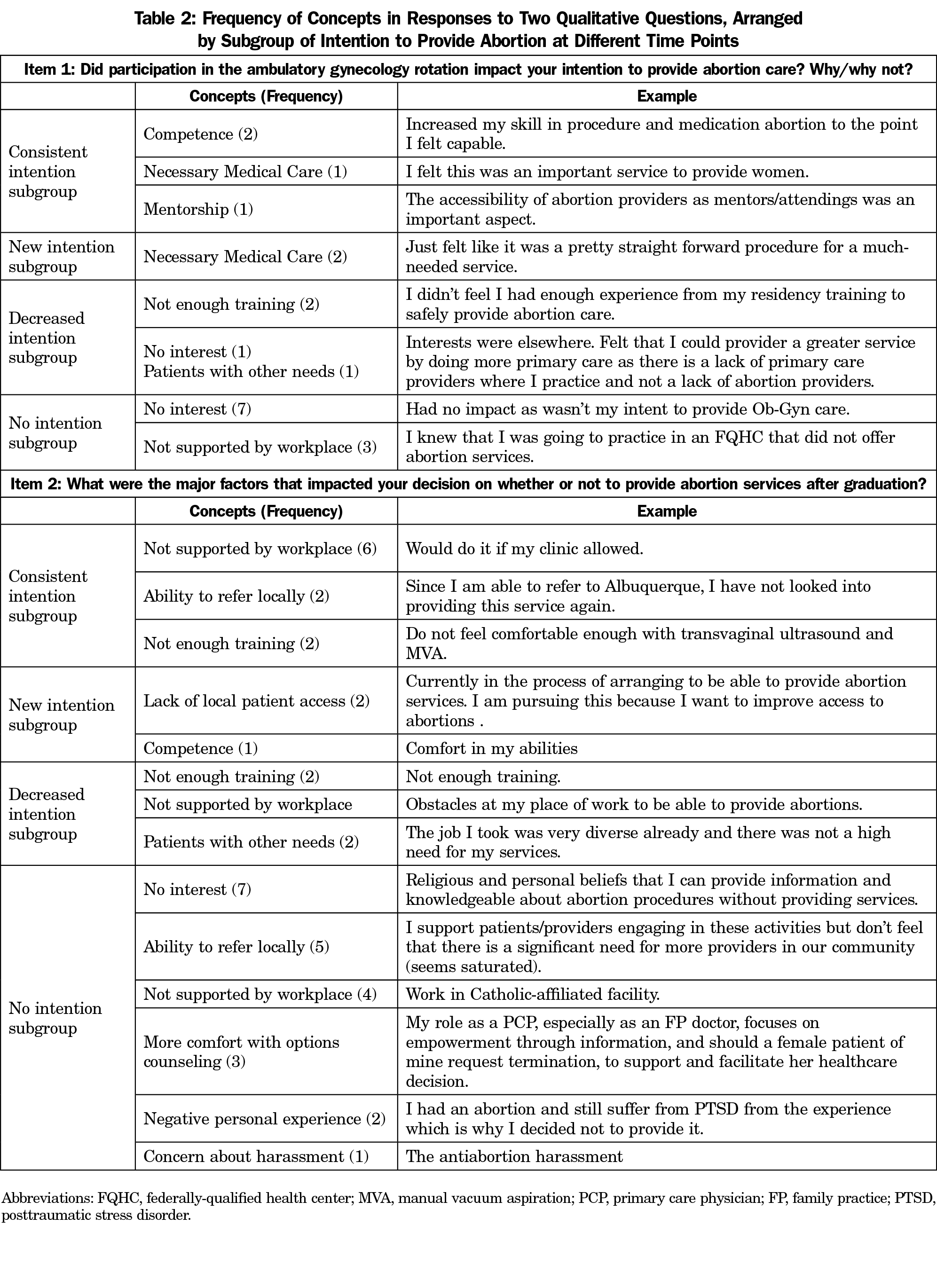

There were 25 open-ended responses to the question, “Did participation in the ambulatory gynecology rotation impact your intention to provide abortion care? Why/why not?” Content analysis revealed the concepts of “no interest” (8 x), “necessary medical care” (3 x), “not supported by (anticipated) workplace” (3 x), “competence” (2 x), and “mentorship” (1 x).

There were 42 open-ended responses to the question, “What were the major factors that impacted your decision on whether or not to provide abortion services after graduation?” The content analysis revealed the concepts of “not supported by workplace” (12 x), “ability to refer locally” (7 x), “no interest” (7 x), “more comfort with options counseling” (3 x), “supportive workplace” (2 x), “negative personal experience” (2 x), “competence” (1 x) and “concern about harassment” (1 x).

Respondents were split into four subgroups based on binary responses regarding intention to provide abortion care at two time points. The Consistent Intention Subgroup contained 13 graduates who intended to provide abortion care in residency and after graduating. The New Intention Subgroup contained five graduates who did not intend to provide abortion services in residency and changed to intending to after graduation. The Decreased Intention Subgroup contained five graduates who intended to provide abortion care in residency, and no longer intended to after graduation. The No Intention Subgroup contained 31 graduates who did not intend to provide abortion services at either time point.

Table 2 shows the frequency of concepts in open-ended responses arranged by the above subgroups.

Summary of Content Analysis by Subgroup

Consistent Intention Subgroup. Competence is the main theme in those who continue to intend to provide abortions after residency, but workplace support is the main factor affecting their practice.

New Intention Subgroup. Viewing abortion care as medically necessary care is the main theme in those who changed their intention to provide abortions after residency, and perception of limited patient access is the main factor affecting their practice.

Decreased Intention Subgroup. Lack of training is the main theme in those who no longer intend to provide abortions after residency, and factors affecting their practice are varied.

No Intention Subgroup. The most frequent theme during training and in practice is having no interest.

Our findings were consistent with low rates of family medicine and Ob-Gyn doctors performing abortions after residency.3,13 Workplace restrictions were the main barrier to practice identified, which indicates the importance of education on addressing systemic barriers, such as incorporating guides like Integrating Abortion into Community Health Centers.14

At UNMFMR, the two training sites for abortion care provide procedural and medication abortions and perform routine ultrasounds. Graduates’ false belief about needing ultrasound shows a need to educate residents about no touch medical abortion protocols for providing medication abortions without ultrasound or over telephone, when appropriate.15-17

Limitations of this study include narrow generalizability to other institutions. The response rate may contribute to sample bias. Also, respondents who never intended to provide abortion care may have interfered with the barrier analysis.

The new methodology of analyzing four subgroups based on intention to provide abortion care offers understanding of how graduates make this decision. The “New Intention” subgroup offers insight into how to enhance training to increase intention and actual provision of abortion care. For example, though the theme of limited patient access was not present in our literature review, it was the most frequent theme in this subgroup. These implications should be explored in a larger sample in the future.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: This study was previously presented as “Abortion Care in Graduates of the University of New Mexico Family Medicine Program: A Mixed Methods Exploration,” at the 2020 Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Virtual Conference, August 24-27, 2020.

References

- Jones RK, Witwer E, Jerman J. Abortion Incidence and Service Availability in the United States, 2017. [Internet] New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2019. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/abortion-incidence-service-availability-us-2017. Accessed July 24, 2020.

- Weidner A, Stevens N, Shih G. Associations between program-level abortion training and graduate preparation for and provision of reproductive care. Fam Med. 2019;51(9):750-755. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.219951

- Patel P, Narayana S, Summit A, et al. Abortion provision among recently graduated family physicians. Fam Med. 2020;52(10):724-729. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.300682

- Grossman D, Grindlay K, Altshuler AL, Schulkin J. Induced abortion provision among a national sample of obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(3):477-483. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003110

- Srinivasulu S, Maldonado L, Prine L, Rubin SE. Intention to provide abortion upon completing family medicine residency and subsequent abortion provision: a 5-year follow-up survey. Contraception. 2019;100(3):188-192. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2019.05.011

- Weidner A, Stevens N, Shih G. Associations between program-level abortion training and graduate preparation for and provision of reproductive care. Fam Med. 2019;51(9):750-755. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.219951

- Summit AK, Lague I, Dettmann M, Gold M. Barriers to and enablers of abortion provision for family physicians trained in abortion during residency. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2020;52(3):151-159. doi:10.1363/psrh.12154

- Goodman S, Shih G, Hawkins M, et al. A long-term evaluation of a required reproductive health training rotation with opt-out provisions for family medicine residents. Fam Med. 2013;45(3):180-186.

- Guiahi M, Lim S, Westover C, Gold M, Westhoff CL. Enablers of and barriers to abortion training. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(2):238-243. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-12-00067.1

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

- Roberts K, Dowell A, Nie J. Attempting rigour and replicability in thematic analysis of qualitative research data; a case study of codebook development. BMC Med Res Methodo; 2019:19-66.

- Content Analysis [Internet]. Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. 2019. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/research/population-health-methods/content-analysis. Accessed October 26, 2020.

- Steinauer JE, Turk JK, Pomerantz T, Simonson K, Learman LA, Landy U. Abortion training in US obstetrics and gynecology residency programs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jul;219. obstetrics and gynecology practice. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2010;42(3):146-151.

- Integrating Abortion into Community Health Centers [Internet]. Reproductive Health Access Project. 2019. https://www.reproductiveaccess.org/resource/faqs-integrating-abortion-community-health-centers/. Accessed July 24, 2020.

- Schonberg D, Wang L-F, Bennett AH, Gold M, Jackson E. The accuracy of using last menstrual period to determine gestational age for first trimester medication abortion: a systematic review. Contraception. 2014;90(5):480-487. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2014.07.004

- Raymond EG, Grossman D, Mark A, et al. Commentary: No-test medication abortion: A sample protocol for increasing access during a pandemic and beyond. Contraception. 2020;101(6):361-366. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2020.04.005

- No Touch Medical Abortion Protocol [Internet]. Reproductive Health Access Project. 2020. https://www.reproductiveaccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/03-2020-no-touch-MAB.pdf. Accessed July 24, 2020.

There are no comments for this article.