Background and Objectives: In family medicine, leadership is critical for health care delivery, advancing curricula, research, and quality improvement. Systematic reviews of leadership development programs in health care identify limitations, calling for innovative designs and rigorous assessment. Our objective was to evaluate the impact of applying master class principles to leadership development in academic family medicine.

Methods: We used mixed methods to assess the impact of an innovative master class program on 15 emerging leaders in a large academic department of family medicine. The program consisted of five sessions where family physician masters shared their wisdom, techniques, and feedback with promising leaders. Quantitative evaluation involved participants’ ratings of each session’s content and delivery using a 5-point Likert scale. We assessed postcourse semistructured interviews with participants qualitatively using descriptive thematic content analysis.

Results: Individual sessions were highly evaluated, with a combined mean of 4.82/5. Qualitative thematic analysis identified self-perceived increased effectiveness in leadership activities; increased confidence as a leader; increased motivation to be a leader; and perceptions of value from the program, contributing to what participants described as unexpected potential change within themselves. Themes related to effectiveness of the program were practical advice; networking; diverse topics; accessible speakers sharing personal stories; and small-group, informal, early-evening format.

Conclusions: Master class concepts can be adapted to leadership development in academic family medicine, with evidence of early positive impact on participants’ self-perception of leadership skills and confidence. Further research is warranted to assess organizational impact and applicability to other settings.

Leadership in family medicine (FM) is crucial for reshaping health care delivery, evolving curricula, expanding research, and focusing on quality improvement.1-4 The growing importance of leadership in medicine is reflected in its inclusion as a competence for trainees and practitioners.5-8 Leadership development programs have proliferated, yet systematic reviews find limited evidence of impact and call for rigor in identifying effective

innovations.9-15

We postulated that a leadership development program modelled on music master classes could address an identified gap in supporting emerging leaders in our academic FM department. The defining features of master classes are that accomplished students are invited or apply to perform in a group setting for a recognized master, who demonstrates and explains techniques and provides feedback and advice.16 Previous reports on master classes in health care include only some of these attributes.17-21

Setting

The Department of Family and Community Medicine (DFCM) at the University of Toronto is diverse and widely distributed, comprising over 1,700 faculty at 14 hospital-affiliated sites and multiple community practices.

Intervention

Our program is described in Figure 1. The precourse assignment adapted the performance attribute of music master classes. In some sessions, the masters stimulated discussion and advice regarding participants’ descriptions of their leadership challenges, but there was no grading or critique of individuals.

Design and Analysis

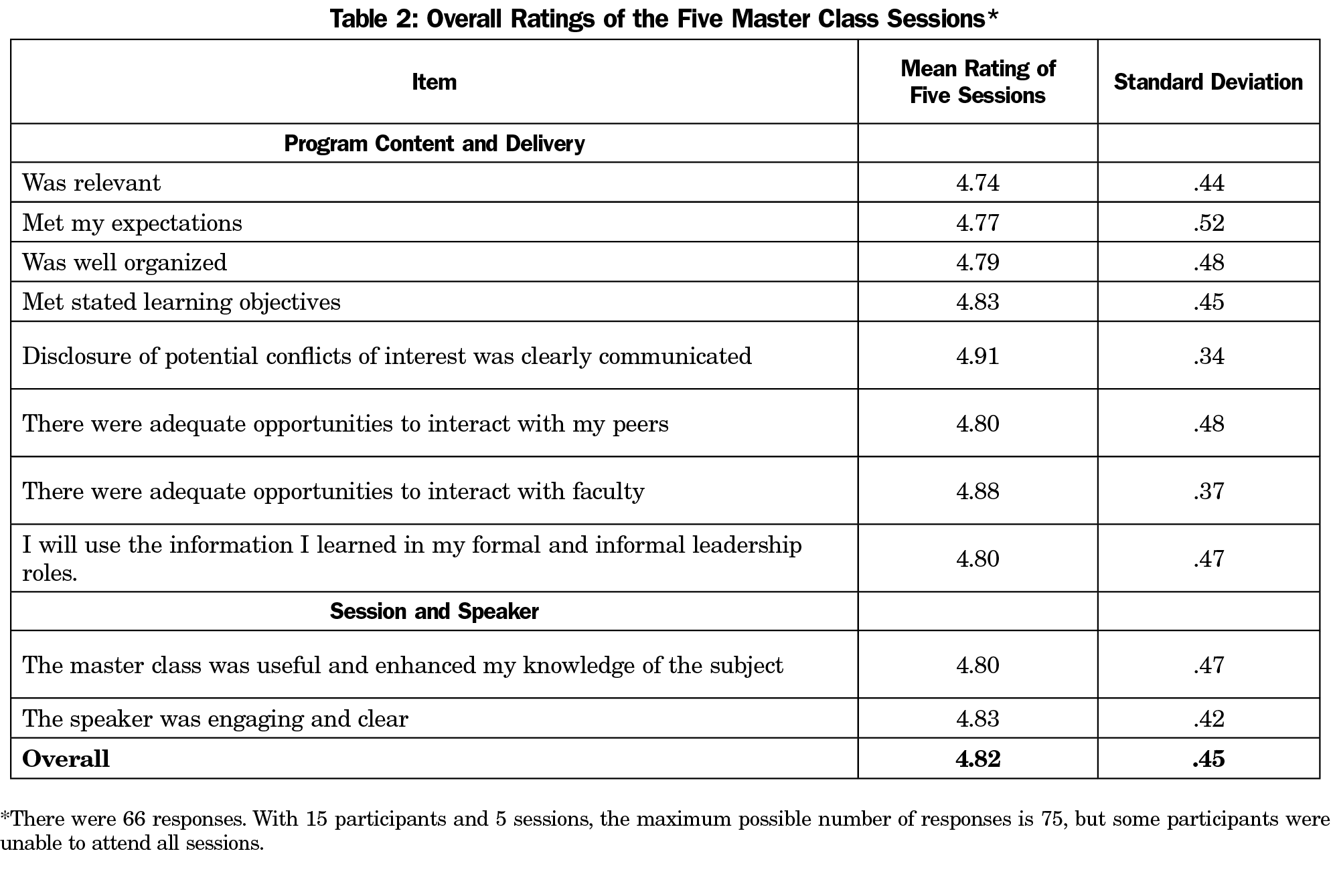

We used mixed methods to capture quantitative ratings of sessions and participants’ experience.35 The quantitative evaluation was a questionnaire following each session.36 Participants rated content, process, and speakers on 10 attributes using a 5-point Likert scale.

For the qualitative evaluation, semistructured participant interviews were conducted 6 to 12 weeks following the last session by an independent qualitative researcher (S.C.) using a semistructured interview guide (Figure 2). Telephone interviews lasted 30-60 minutes, were audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. Data were initially organized and coded by S.C. in Dedoose, an online qualitative data software. Initial data organization mapped coded excerpts to interview questions with layered coding capturing more specific accounts or experiences. Following this, team members (S.C., J.C.C., D.G.W.) independently reviewed the transcripts using descriptive thematic analysis.22 All team members then discussed and agreed upon themes. Any differences were resolved through discussion. Team members conducted a separate analysis of the participants’ precourse assignments. Two researchers (J.C.C., D.G.W.) identified themes independently and resolved any differences through discussion.

The Research Ethics Board of the University of Toronto approved the study.

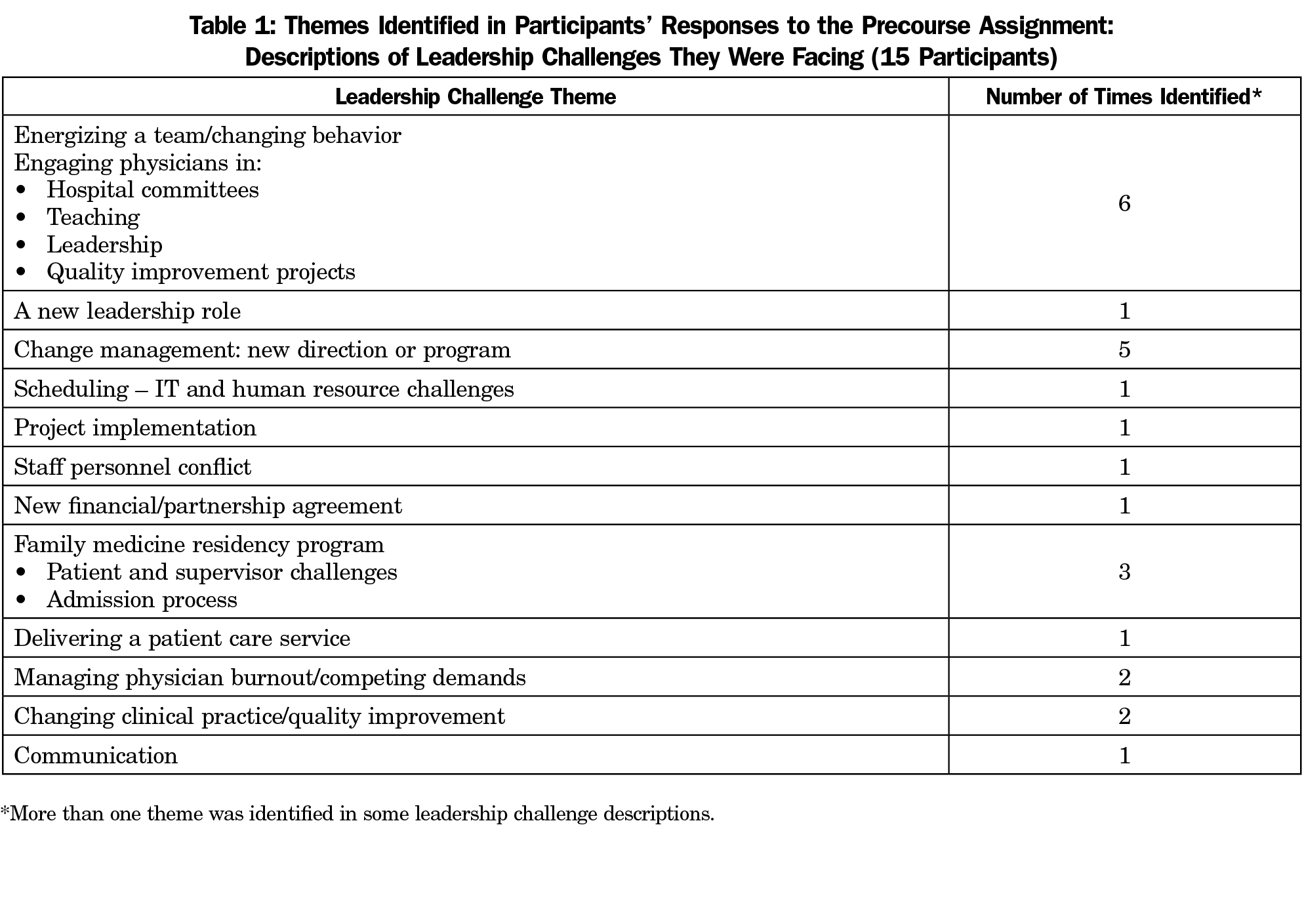

There were 15 family physician participants, 13 women and 2 men. Themes in participants’ precourse assignment are listed in Table 1.

Quantitative Results

Table 2 shows the course ratings for the session attributes. The mean rating for all five sessions was 4.82 out of 5 (SD 0.45).

Qualitative Findings

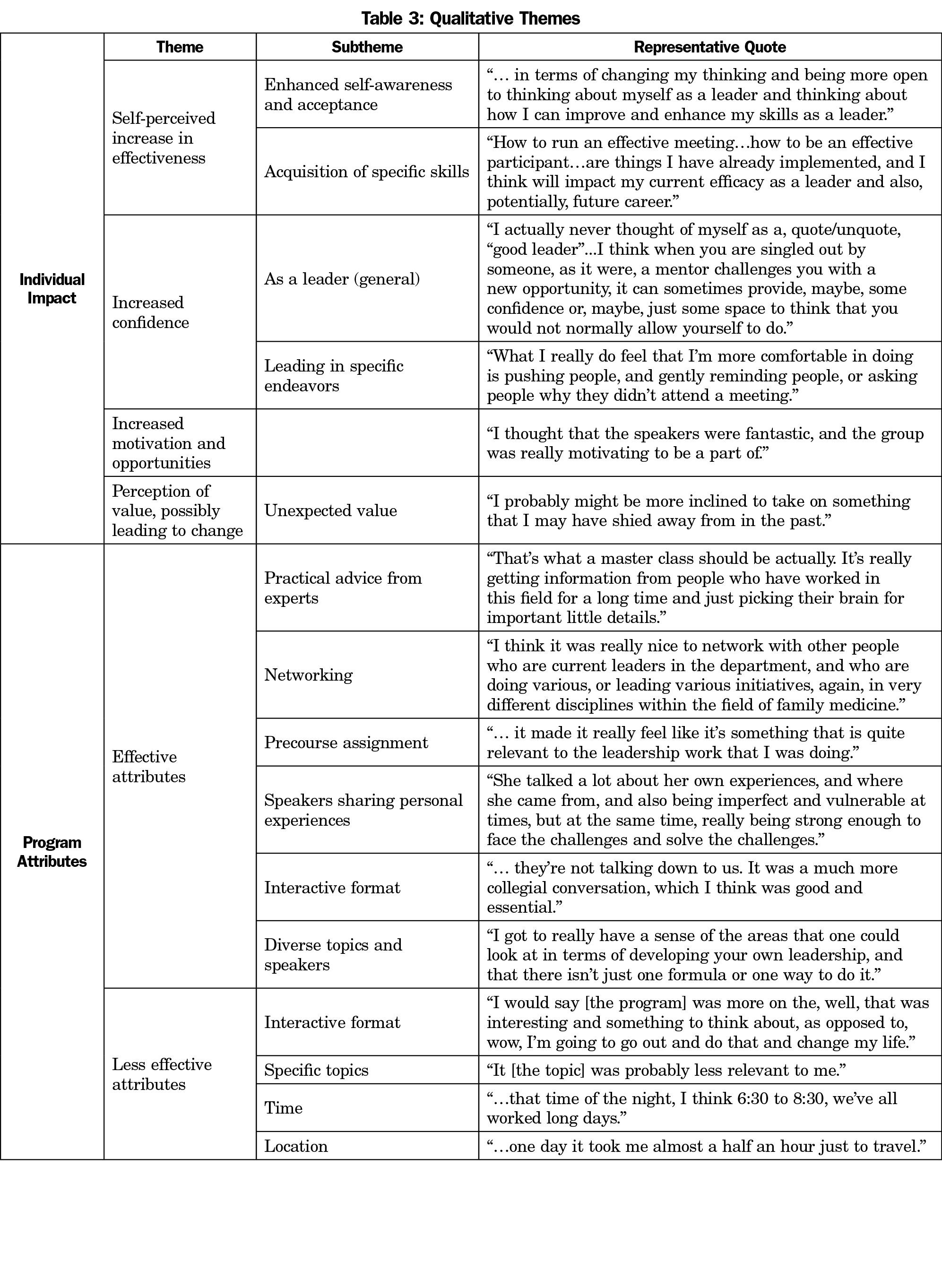

All 15 participants agreed to be contacted for postcourse interviews; 10 scheduled and completed interviews. Participants described the impact of the master class program and program attributes that were more or less effective. They described themselves as increasing in effectiveness, confidence, and motivation in leadership and that the program had contributed to unexpected potential changes within themselves. This could manifest as enhanced openness to new endeavours such as research or speaking to a reporter. Participants described changes that they had already incorporated, such as new skills, recognition of inherent abilities, and reinvigoration as a faculty member. Table 3 gives themes with representative quotes.

Participants identified some program attributes as both effective and ineffective. The interactive format was appreciated, but perceived by some as less transformative or exciting. Timing and location were considered problematic by those travelling greater distances, but dining together and being away from work were valued. Diverse topics and speakers were assets, but specific ones were identified in some interviews as less relevant.

This evaluation of a leadership development program designed on the principles of music master classes shows evidence of early positive impact based on participants’ self-evaluation. This program differs from previous reports of master classes in health care by incorporating key defining characteristics: course leaders who are recognized masters, participants selected on demonstrated ability, a performance consisting of a precourse assignment, and a highly interactive format.17-21

Qualitative findings indicate successful incorporation of qualities that Souba identified as crucial for building leadership capacity: “ingredients that catalyze and enhance human connectivity, augment social capital, and activate leadership.”23 Increased confidence, motivation, and self-awareness contribute to leadership activation. The opportunity to form new relationships with colleagues and potential mentors represents a significant benefit for a large, widely dispersed academic enterprise.33

Our findings align with Steinert’s review of faculty development initiatives to promote leadership in medical education.12 These include high levels of satisfaction, greater awareness of personal strengths and limitations, increased motivation, confidence and networking, gains in knowledge and skills, and increased awareness of leadership roles. Systematic reviews identified the reliance on lectures and didactic methods as a weakness of physician leadership development programs.11,13 The interactive format of the master class addresses this concern.

The selection process incorporated a key recommendation from the Leadership Development Task Force of the Council of Academic Family Medicine, stating:

In developing the leadership pipeline, current leaders should look to colleagues, including junior colleagues, who may not have self-identified as leaders but who have demonstrated leadership potential.

Study limitations include studying a small cohort at a single institution, lack of a control group, short follow-up time, and no assessment of organizational impact. Pre/post comparison is commonly employed for course evaluation; we chose qualitative methods to gain in-depth understanding of the meaningful and useful aspects of the program that contributed to growth and change. Although interviews could be scheduled with only 10 of 15 participants, the qualitative data is detailed, with important recurring themes evident in the descriptive thematic analysis. The precourse assignment is a limited adaptation of the performance attribute of master classes. Ericsson states that rigorous measurement of superior performance in medicine is difficult but possible, yet none of his examples address leadership performance.24,25 Enhancing the performative element remains a challenge and opportunity for further development.

An unexpected finding was the 13 to 2 ratio of female to male participants, significantly greater than the departmental ratio of 52:48. Criteria for selecting participants included no reference to gender, and 10 of the 15 nominating chiefs were men. Continuing the program will determine if this occurrence was random. Nevertheless, this group represents a cohort of emerging leaders with potential to redress the gender imbalance among senior roles.

Further research is needed to assess the longer-term impact on participants and the organization. Although not explicitly modelled after master classes, leadership development programs in medicine often incorporate similar elements. Intentional application of master class principles has the potential to enhance existing programs. Evaluating virtual delivery is relevant for broadening the scope and accessibility of this approach.

Master class principles can be adapted to leadership development in academic FM, with qualitative evidence of early positive impact based on participant self-assessment.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was supported by an Art of the Possible educational grant from the Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto.

Presentations: This research has been previously presented as follows:

White DG, Glazier R, Martin D, Shapiro M, Whitehead C, Carroll J, Freeman R, Crann S, Kidd M. The Master Class Series in Family Doctor Leadership: Evaluation of a new approach to leadership development (poster and oral presentation). Leaders in Healthcare 2019. November 5-6, 2019. Birmingham, England, UK.

White DG, Glazier R, Martin D, Shapiro M, Whitehead C, Carroll J, Freeman R, Crann S, Kidd M. The Master Class Series in Family Doctor Leadership: Evaluation of a new approach to leadership development (poster presentation). Family Medicine Forum 2019, College of Family Physicians of Canada. October 30, 2019. Vancouver, BC, Canada.

White DG, Glazier R, Martin D, Shapiro M, Whitehead C, Carroll J, Freeman R, Crann S, Kidd M. Evaluating a Master Class in Family Doctor Leadership:

Completed Research (oral presentation). November 20, 2020. North American Primary Care Research Group Virtual Conference.

References

- Wender R, Borkan J, Davis A; Association Of Departments Of Family Medicine. A pivotal time for family medicine leadership development. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):182. doi:10.1370/afm.1236

- Roberts RG, Snape PS, Burke K. Task Force Report 5. Report of the Task Force on Family Medicine’s Role in Shaping the Future Healthcare Delivery System. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 1):S88-S99. doi:10.1370/afm.138

- Phillips RL Jr, Brundgardt S, Lesko SE, et al. The future role of the family physician in the United States: a rigorous exercise in definition. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(3):250-255. doi:10.1370/afm.1651

- Newton WP, DuBard CA. Shaping the future of academic health centers: the potential contributions of departments of family medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(suppl 1):S2-S11. doi:10.1370/afm.587

- Neeley SM, Clyne B, Resnick-Ault D. The state of leadership education in US medical schools: results of a national survey. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1301697. doi:10.1080/10872981.2017.1301697

- Shaw E, Oandasan I, Fowler N. A competency framework for family physicians across the continuum. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2017.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, (ACGME). Family Medicine Milestones. 2nd ed. Chicago: ACGME; 2019. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/FamilyMedicineMilestones.pdf?ver=2020-09-01-150203-400. Accessed April 9, 2021.

- NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement and Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Medical Leadership Competency Framework. 3rd ed. Coventry, UK: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement; 2010.

- Straus SE, Soobiah C, Levinson W. The impact of leadership training programs on physicians in academic medical centers: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88(5):710-723. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828af493

- Seidman G, Pascal L, McDonough J. What benefits do healthcare organisations receive from leadership and management development programmes? A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Leader. 2020;4(1):21-36. doi:10.1136/leader-2019-000141

- Moore Simas TA, Cain JM, Milner RJ, et al. A Systematic Review of Development Programs Designed to Address Leadership in Academic Health Center Faculty. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2019;39(1):42-48. doi:10.1097/CEH.0000000000000229

- Steinert Y, Naismith L, Mann K. Faculty development initiatives designed to promote leadership in medical education. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 19. Med Teach. 2012;34(6):483-503. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2012.680937

- Frich JC, Brewster AL, Cherlin EJ, Bradley EH. Leadership development programs for physicians: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):656-674. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-3141-1

- Lucas R, Goldman EF, Scott AR, Dandar V. Leadership Development Programs at Academic Health Centers: Results of a National Survey. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):229-236. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001813

- Onyura B, Crann S, Tannenbaum D, Whittaker MK, Murdoch S, Freeman R. Is postgraduate leadership education a match for the wicked problems of health systems leadership? A critical systematic review. Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8(3):133-142. doi:10.1007/s40037-019-0517-2

- Hanken IM. Teaching and Learning Music Performance: The Master Class. Finnish Journal of Music Education. 2008;11(1-2):26-36.

- Toh CH, Strivens J, Guenova M, Modok S. A master class for European hematology. Haematologica. 2014;99(6):949-951. doi:10.3324/haematol.2014.107540

- Voll J, Bragg D, Maxwell-Armstrong C. Master class in administration skills – An innovative learning experience for future foundation doctors. Int J Surg. 2013;11(8):699. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2013.06.599

- Turner AM, Facelli JC, Jaspers M, et al. Solving Interoperability in Translational Health. Perspectives of Students from the International Partnership in Health Informatics Education (IPHIE) 2016 Master Class. Appl Clin Inform. 2017;8(2):651-659. doi:10.4338/ACI-2017-01-CR-0012

- Duffield C. A Master Class for nursing unit managers: an Australian example. J Nurs Manag. 2005;13(1):68-73. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2004.00489.x

- Webster M, Remedios L. Making the student the master in the master class. Physiotherapy. 2015;101:e1272-e1273. doi:10.1016/j.physio.2015.03.1182

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006; 3(2):77-101, doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Souba WW. New ways of understanding and accomplishing leadership in academic medicine. J Surg Res. 2004;117(2):177-186. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2004.01.020

- Ericsson KA. Acquisition and maintenance of medical expertise: a perspective from the expert-performance approach with deliberate practice. Acad Med. 2015;90(11):1471-1486. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000939

- Ericsson KA. Deliberate Practice and the Acquisition and Maintenance of Expert Performance in Medicine and Related Domains. Academic Medicine.Research in Medical Education Proceedings of the Forty-Third Annual Conference November 7-10. 2004;79(10(Supplement):S70,S81, Otober 2004. doi:10.1097/00001888-200410001-00022

There are no comments for this article.