Background and Objectives: Diversity, inclusion, and health equity (DIHE) are integral to the practice of family medicine. Academic family medicine has been grappling with these issues in recent years, particularly with a focus on racism and health inequity. We studied the current state of DIHE activities in academic family medicine departments and suggest a framework for departments to become more diverse, inclusive, antiracist, and focused on health equity and racial justice.

Methods: As part of a larger annual membership survey, family medicine department chairs were asked for their assessment of departmental DIHE and antioppression activities, and infrastructure and resources committed to increasing DIHE.

Results: More than 60% of family medicine department chairs participating in this study rate their departments highly in promoting DIHE and antioppression, and 66% of chairs report an institutional infrastructure that is working well. Just over half of departments or institutions have had a climate survey in the past 3 years, 47.3% of departments have a diversity officer, and 26% of departments provide protected time or resources for a diversity officer.

Conclusions: The majority of family medicine department chairs rate their departments highly on DIHE. However, only 50% of departments have formally assessed climate in the past 3 years, fewer have diversity officers, and even fewer invest resources in their diversity officers. This disconnect should motivate academic family medicine departments to undertake formal self-assessment and implement a strategic plan that includes resource investment in DIHE, measurable outcomes, and sustainability.

Diversity, inclusion, and health equity (DIHE) are central principles of family medicine as we care for patients and communities. Patients express higher satisfaction,1,2 better communication,3 and more adherence4 with health care providers whose race and ethnicity or language2 are congruent with theirs.1,5 These factors may be associated with better health outcomes6 and reduction of health inequity.7,8

The impact of physician workforce disparities on patient care is still being characterized9 and the health care workforce is not sufficiently diverse.10 The specialty of family medicine has a legacy of addressing the breadth of issues that affect the health of patients and communities,11 but despite a higher proportion of underrepresented in medicine (URM) faculty than other specialties (11% vs 7% in 2015),12 neither the family medicine trainee workforce nor academic family medicine leadership currently match the demographics of the communities we serve13,14 (28% Black, Indigenous, and People of Color in 201915).

Structural racism, lack of diversity, and gaps in health equity have pervaded health care for generations,16 and the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color is only the most recent example. Academic family medicine is currently defining its mission and role regarding DIHE. The editors of ten family medicine journals have issued a call for action to address systemic racism and eliminate health disparities, jointly committing to scholarship in this area.17 The mission of the Association of Departments of Family Medicine (ADFM) is to support academic departments of family medicine to lead and achieve their full potential in care, education, scholarship, and advocacy to promote health and health equity. In 2019, the ADFM Board of Directors established a DIHE Committee with three working groups to develop smart goals, to embed DIHE into all ADFM committee work, and to examine best practices.18 The ADFM Best Practices working group, composed of the authors of this study, aimed first to characterize the current state of DIHE efforts in academic family medicine departments.

Strategies for increasing faculty diversity in academic medicine have been characterized,19,20 but despite the commitment of academic family medicine leadership, the current status of DIHE engagement in departments of family medicine is not known. We surveyed family medicine department chairs about DIHE efforts in their departments. We examined the investment of departments in DIHE activities, hypothesizing that while DIHE efforts are common with departments of family medicine, well-defined and well-funded efforts would be less widespread.

Survey

In 2020, ADFM conducted its annual member survey completed by chairs of ADFM member departments, which includes nearly all departments of family medicine at allopathic medical schools in the United States, as well as a few allopathic Canadian departments, osteopathic departments, and departments in large regional medical centers with a robust educational mission. The survey was sent electronically to all 165 member departments on June 29, 2020; after several reminders, the survey was closed on September 2, 2020. Review of survey results for this study was approved under minimal risk review by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. The Best Practices working group of the ADFM DIHE Committee met virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic to analyze the current state of DIHE represented by the survey and to recommend best practices for academic family medicine departments.

Survey Questions

The annual member survey contained at total of 86 questions, on such topics as research, health care delivery transformation, and faculty promotions. Of these, the seven questions in the diversity/health equity section were relevant to this project. These items are listed in Table 1. Three of the questions were combined to create a single measure of commitment to the diversity/inclusion officer, as shown in the table.

Analysis

Responses to survey items were summarized by frequencies; χ2 and Fisher’s Exact tests for categorical variables (based on cell frequencies) examined associations between survey items. We performed analyses with SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) at an α level of 0.05.

A total of 94 of the 165 invited member departments responded (57% response rate). Sixty-six percent of chairs participating in this study reported their institution had an infrastructure for diversity and inclusion that was working well. Less than half (47.3%) of departments had a designated diversity/inclusion officer, and 53.7% of those positions had a pathway that led to career advancement. Approximately 25% of departments invested full-time equivalent (FTE) or resources in diversity and inclusion. More than half (53.2%) of chair respondents reported receiving data from a climate survey conducted by the institution or the department in the last 3 years.

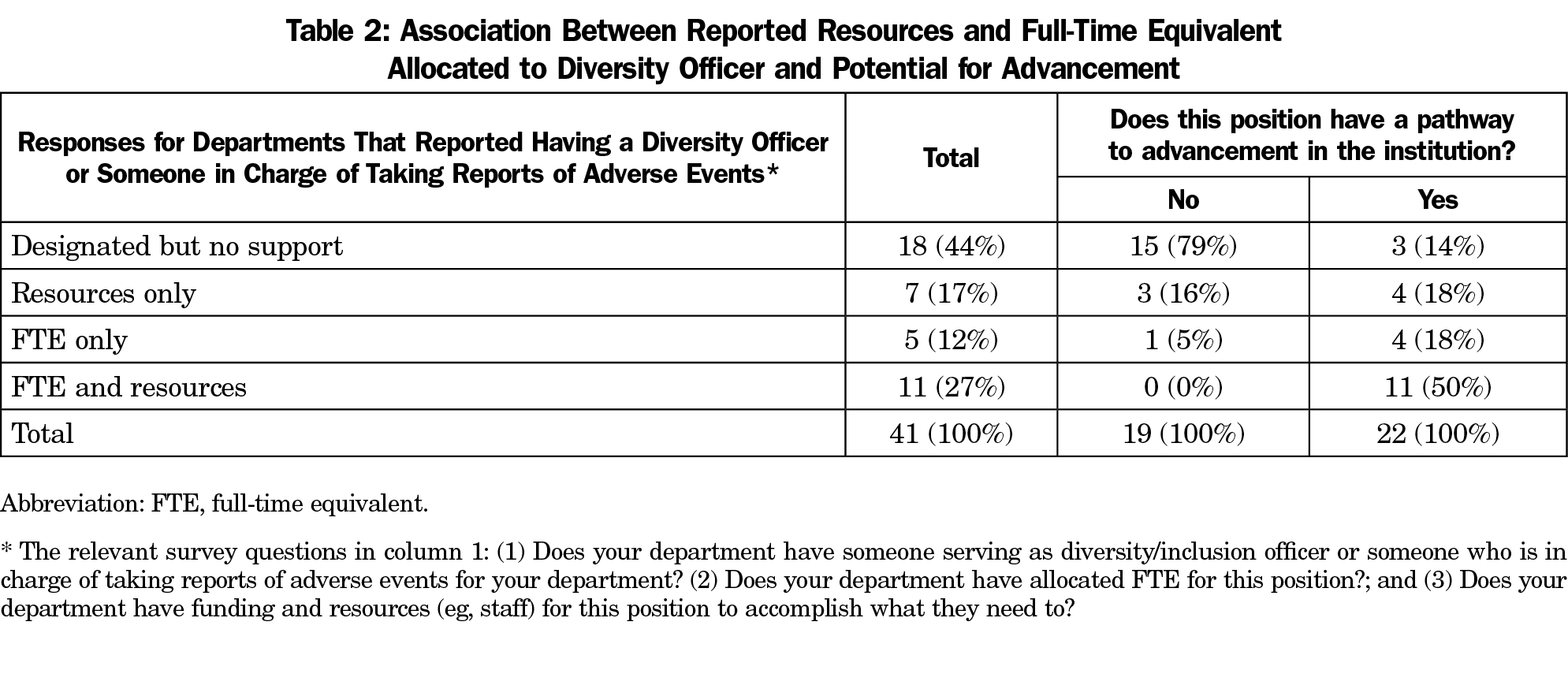

Among those reporting a designated diversity/inclusion officer, resource commitment to that officer was significantly associated with the position having a pathway to advancement in the institution or department, based on Fisher’s exact test (P<.001). Higher level of commitment in terms of FTE and resources was associated with the position having a pathway to advancement in the institution. (Table 2)

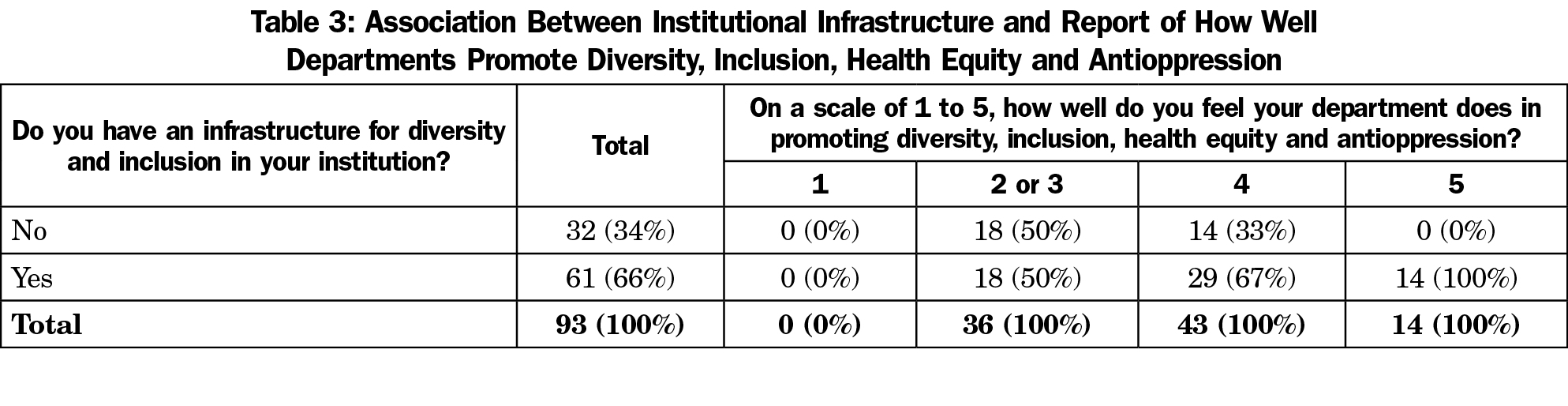

Respondents who reported an institutional infrastructure for diversity and inclusion were significantly more likely to give higher ratings to their department on promoting DIHE and anti-oppression, (Fisher’s exact test, P=.002; Table 3). Neither institutional infrastructure nor departmental promotion of DIHE was statistically significantly associated with the commitment measure.

More than 60% of family medicine department chairs in this study rated their departments highly in promoting DIHE and antioppression, and 66% reported an institutional infrastructure that is working well. However, just over half of departments have had a climate survey to measure the engagement and perceptions of the workplace in the past 3 years. Fewer than half of respondents reported having a diversity officer, which is a key element of a diversity infrastructure outlined in the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Diversity and Inclusion Strategic Planning Guide,21 and only half of those supported the diversity officer with FTE or resources. Lack of support was correlated with a lack of potential advancement in the institution. These findings raise the question of whether the positive self-assessment by department chairs is more reflective of good intentions than strategic action and successful outcomes. Lack of departmental resource investment calls the question whether departments truly prioritize DIHE, unless they rely on a robust larger institutional DIHE infrastructure.

This study illustrates that DIHE is not uniformly strong within academic family medicine departments. We suggest a framework for academic family medicine departments to become more diverse, inclusive, antiracist, and focused on health equity and racial justice. We believe that departments should (1) begin with self-assessment, (2) use that assessment to create a strategic plan, (3) create and support a DIHE infrastructure, and (4) regularly measure and report outcomes of those efforts. These steps will align family medicine departments with efforts across academic medicine.22

1. Assessment

Despite high self-rating, only half of the participating departments had data from a climate survey in the past 3 years. To obtain such data, the Diversity Engagement Survey is one validated diagnostic and benchmarking tool for assessing an academic medical institution’s diversity and inclusion with respect to faculty, staff, and students.23 Second, a community environmental scan can identify issues outside of health care that are critical to advancing health equity and identify the degree of alignment of the department with its community.24 Finally, a departmental strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis can inform the work ahead.

2. Strategic Plan

An effective strategic plan should use the self-assessment to further DIHE as part of the institution’s culture and values. Institutions can leverage the AAMC Diversity and Inclusion Strategic Planning Toolkit10 from the initial planning phases through implementation, learning from practical examples at each step. Another road map for increasing diversity and reducing health disparities is Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change, a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.25 Interventions should address cultural and structural issues as well as individual issues.26 The COVID-19 pandemic has added another layer of complexity to making decisions and strategic plans in a crisis. Whether it is this pandemic or the next one, the National Inclusive Excellence Leadership Academy Center for Strategic Diversity Leadership & Social Innovation suggests a four-point Crisis Action Framework: (1) make culturally relevant decisions, (2) support diverse communities, (3) communicate thoughtfully and inclusively, and (4) digitize inclusive excellence.27

3. DIHE Infrastructure

More than half of family medicine department chairs in this study rated their departments highly in promoting DIHE and antioppression and reported that the infrastructure for diversity and inclusion in their institutions was working well. High rating of departments correlated with having an institutional infrastructure, and none of the departments that lacked institutional infrastructure reached the highest self-rating for DIHE. An effective DIHE infrastructure requires sustained action from the highest level of an organization down, as well as from the grassroots up. Leadership must articulate DIHE as a strategic priority of the institution and appoint an advisory council that includes all major sectors of the organization. Family medicine departments must have a DIHE director with the authority, support, tools, and resources to champion those efforts,28 who can lead a departmental diversity council. The DIHE structure must be accountable, transparent, and report regularly,24 and DIHE leaders must have a pathway to career advancement.

4. Outcome Accountability and Dissemination

Departments should identify key metrics for tracking and dissemination, using published benchmarks from industry29 or guidelines from academic medicine.10 If a department is focused on increasing staff diversity and creating a more inclusive environment, for example, demographic and climate survey data can be collected longitudinally. These data should be shared in a sustainable manner with deans and other internal stakeholders, compared within the institution and across departments of family medicine, and disseminated to external stakeholders. Successes supported by data can be replicated, while failures can promote learning and enable revision and redirection. Instead of relying on narrative reports of “best practices,” departments should measure, analyze, and publish outcomes to build evidence-based literature. Examples of this work include the AAMC’s MedEdPORTAL Diversity, Inclusion and Health Equity Collection30 and the Annals of Family Medicine’s Shared Bibliography on System and Health Disparities.31 Departments of family medicine must commit to adding to this literature.

Limitations of this study included a 57% response rate and self-recall bias. The ranking of one to five in self-rating of diversity lacked description and directionality of each numerical response, leaving room for interpretation. Demographic data for chairs were not obtained. The study occurred at one point in time during a time of change and heightened sensitivity to the issues. Future surveys will measure trends and progress in family medicine department engagement in DIHE with additional questions about demographics and qualitative responses regarding actions taken in the past year.

This survey of academic family medicine department chairs identified that while over half of the responders rated themselves highly, there is considerable opportunity for more rigorous assessment, planning, and sustainable DIHE infrastructure. Future surveys may reveal a drop in department chair satisfaction with their DIHE infrastructure as more departments embark on their own internal work and soul searching.

Making DIHE a central focus in departments of family medicine will have a widespread impact within the communities we serve, the institutions in which we work, and the health care system as a whole. Continuing the same systems that created these disparities is not an option.

References

- Chen FM, Fryer GE Jr, Phillips RL Jr, Wilson E, Pathman DE. Patients’ beliefs about racism, preferences for physician race, and satisfaction with care. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(2):138-143. doi:10.1370/afm.282

- García JA, Paterniti DA, Romano PS, Kravitz RL. Patient preferences for physician characteristics in university-based primary care clinics. Ethn Dis. 2003;13(2):259-267.

- Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):907-915. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00009

- Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, Haidet P. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(3):198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821

- Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, Bindman AB. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(9):997-1004. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.9.997

- Marcella A, Garrick O, Graziani G. Does Diversity Matter for Health? Experimental Evidence from Oakland. Am Econ Rev. 2019;109(12):4071-4111. doi:10.1257/aer.20181446

- Ibrahim SA. Physician Workforce Diversity and Health Equity: It Is Time for Synergy in Missions! Health Equity. 2019;3(1):601-603. doi:10.1089/heq.2019.0075

- Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, Bor DH, McCormick D. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):289-291. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12756

- Silver JK, Bean AC, Slocum C, et al. Physician workforce disparities and patient care: a narrative review. Health Equity. 2019;3(1):360-377. doi:10.1089/heq.2019.0040

- Diversity and Inclusion Strategic Planning Toolkit. Association of American Medical Colleges. Accessed November 22, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/services/member-capacity-building/diversity-and-inclusion-strategic-planning-toolkit

- Stephens GG. Family medicine as counterculture. Fam Med. 1989;21(2):103-109.

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Gaglioti AH, Liaw WR, Bazemore AW. Increasing family medicine faculty diversity still lags population trends. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(1):100-103. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160211

- Coe C, Piggott C, Davis A, et al. Leadership pathways in academic family medicine: focus on underrepresented minorities and women. Fam Med. 2020;52(2):104-111. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.545847

- Xierali IM, Hughes LS, Nivet MA, Bazemore AW. Family medicine residents: increasingly diverse, but lagging behind underrepresented minority population trends. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(2):80-81.

- United States 2019 census. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=2019%20demographics&tid=ACSCP1Y2019.CP05

- Byrd WM, Clayton LA. Race, medicine, and health care in the United States: a historical survey. J Natl Med Assoc. 2001;93(3)(suppl):11S-34S.

- Sexton SM, Richardson CR, Schrager SB, et al. Systemic racism and health disparities: a statement from editors of family medicine journals. PRiMER Peer-Rev Rep Med Educ Res. 2020;4:30. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2020.370906

- Johnson M, Douglas M, Grumbach K, et al. Advancing diversity, inclusion and health equity to the next level. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(1):89. doi:10.1370/afm.2348

- Peek ME, Kim KE, Johnson JK, Vela MB. “URM candidates are encouraged to apply”: a national study to identify effective strategies to enhance racial and ethnic faculty diversity in academic departments of medicine. Acad Med. 2013;88(3):405-412. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318280d9f9

- Kaplan SE, Gunn CM, Kulukulualani AK, Raj A, Freund KM, Carr PL. Challenges in recruiting, retaining and promoting racially and ethnically diverse faculty. J Natl Med Assoc. 2018;110(1):58-64. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2017.02.001

- American Association of Medical Colleges. Diversity and inclusion in academic medicine: a strategic planning guide. Washington, DC: AAMC; 2014.

- Smith DG. Building institutional capacity for diversity and inclusion in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2012;87(11):1511-1515. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826d30d5

- Person SD, Jordan CG, Allison JJ, et al. Measuring diversity and inclusion in academic medicine: the diversity engagement survey. Acad Med. 2015;90(12):1675-1683. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000921

- Broussard DL, Wallace ME, Richardson L, Theall KP. Building governmental public health capacity to advance health equity: conclusions based on an environmental scan of a local public health system. Health Equity. 2020;4(1):362-365. doi:10.1089/heq.2019.0025

- Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, et al. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):992-1000. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2082-9

- Vassie C, Smith S, Leedham-Green K. Factors impacting on retention, success and equitable participation in clinical academic careers: a scoping review and meta-thematic synthesis. BMJ Open. 2020;10(3):e033480. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033480

- Williams D. The COVID-19 DEI Crisis Action Strategy Guide: Recommendations to Drive Inclusive Excellence. Atlanta, GA: Center for Strategic Diversity Leadership & Social Innovation; 2020.

- Hasnain M GE, Yepes-Rios M, et al. Ten tips for dismantling racism: a roadmap for ensuring diversity, equity, and inclusion across the academic continuum. SGIM Forum; 2020.

- O’Mara J, Richter A. Global Diversity and Inclusion Benchmarks: Standards for Organizations Around the World. The Center for Global Inclusion; 2017.

- Diversity, Inclusion, and Health Equity Collection. MedEdPortal. Accessed November 22, 2021. https://www.mededportal.org/diversity-inclusion-and-health-equity

- A Shared Bibliography on Systemic Racism and Health Disparities. Ann Fam Med. Published October 15, 2020. Accessed November 22, 2021. https://www.annfammed.org/content/shared-bibliography-systemic-racism-and-health-disparities

There are no comments for this article.