Background and Objectives: Student-directed activities such as family medicine interest groups (FMIG) and student-run free clinics (SRFC) have been examined to discover their impact on entry into family medicine and primary care. The objective of this review was to synthesize study results to better incorporate and optimize these activities to support family medicine and primary care choice.

Methods: We conducted a comprehensive literature search using PubMed, Scopus, and CINAHL to identify all English-language research articles on FMIG and SRFC. We examined how participation relates to entry into family medicine and primary care specialties. Exclusion criteria were nonresearch articles, review articles, and research conducted outside the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. We used a 16-point quality rubric to evaluate 18 (11 FMIG, seven SRFC) articles that met our criteria.

Results: Of the nine articles that examined whether FMIG participation impacted entry into family medicine, five papers noted a positive relationship, one paper noted unclear correlation, and three papers noted that FMIG did not impact entry into family medicine. Of the seven articles about SRFC, only one showed a positive relationship between SRFC activity and entry into primary care.

Conclusions: Larger-scale and higher quality studies are necessary to determine the impact of FMIG and SRFC on entry into family medicine and primary care. However, available evidence supports that FMIG participation is positively associated with family medicine career choice. In contrast, SRFC participation is not clearly associated with primary care career choice.

There is a consistent need for more family physicians. The family medicine academic community has sought methods to increase the number of students who choose family medicine and other primary care specialties as their future practice.1 Medical schools control admissions processes and curricular materials, and faculty members provide mentorship and act as role models. On the other hand, students proactively engage in extracurricular activities that can shape their identities as future physicians, and ultimately, their career choices. In this review, we examined the effect of family medicine interest groups (FMIG) and student-run free clinics (SRFC) on student entry into family medicine and primary care.

FMIGs in the United States are supported by the American Academy of Family Physicians, and often by departments of family medicine.2,3 The first mention of such interest groups in medical education literature was in 1978, as “Family Practice Club.”4 FMIGs are student-run interest groups with oversight by faculty advisors. They allow students to explore their interests in primary care, gain leadership experience, and be involved in community service.3 SRFCs are also organized by students and aim to provide free medical care and other services for underserved communities. For medical schools, SRFCs fulfill service-learning requirements for accreditation.5 Though SRFCs are specialty-agnostic, it is known that caring for underserved communities is a factor for students choosing family medicine.6 We reviewed publications on FMIG and SRFC because they are common programs across many US medical schools, and the value of investing in FMIG and SRFC by departments of family medicine is unknown.

The literature review was conducted in two stages: a primary and secondary search. In the primary search we considered medical school structures, policies, and practices that promote primary care specialty choice.7 Results from the primary search are described in a scoping review,7 and we used topic-specific articles from the primary search in this focused review.

We conducted a secondary search with search terms “family practice club,” “Family Medicine Interest Group,” “FMIG,” “student-run free clinic,” “mentor,” “mentorship,” and “role model” through PubMed, Scopus, and CINAHL. We selected these additional search terms based on language mapping from the original scoping review. We deduplicated pre-2016 articles that had been identified in the original scoping review. We included papers that met inclusion criteria for role model or mentoring in a separate publication.8

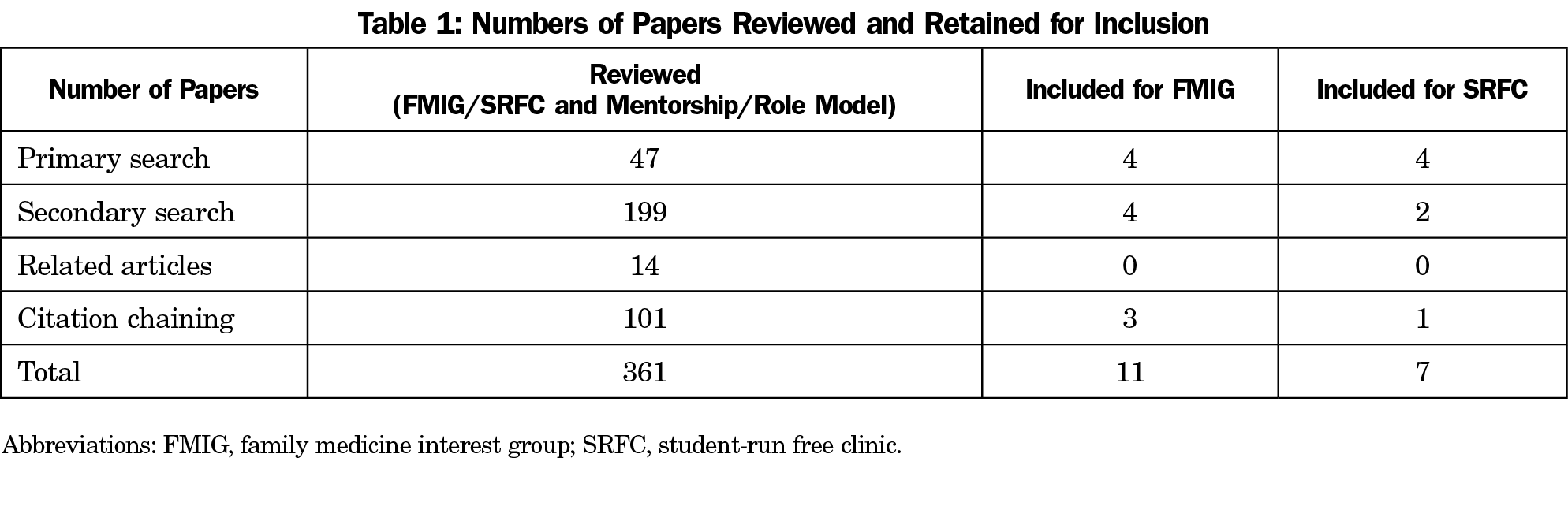

We also reviewed the citations of articles meeting inclusion criteria (citation chaining) to ensure a comprehensive search. In total, we reviewed titles and abstracts of 361 articles (47 from the primary search, 199 from the secondary search, 14 related articles, and 101 after citation chaining). When necessary, the full text of the article was reviewed.

Consistent with the primary search, we selected research papers for inclusion if they were published in English and took place in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, or Canada, based on similarity of educational structure and workforce challenges. Additionally, they needed to relate to the research question, “Do FMIGs and SRFCs impact interest and entry to family medicine?” Papers were included if they included “FMIG” or “SRFC” as either a specific variable in the analysis (for quantitative papers) or as a theme (for qualitative papers). The outcomes of interest were student primary care/family medicine interest, intention to match, or entering a primary care career, as determined by study authors. Concordant with the broader study, nonresearch studies and studies without a primary care outcome were excluded. Where uncertainty about inclusion existed, one or more additional researchers discussed each article until consensus was reached.

Authors T.S. and A.K. conducted a quality review using a previously described rubric to evaluate each of the included articles.7 We compared quality review scores by t test for all articles, FMIG articles, and SRFC articles with clear outcomes. We performed a narrative synthesis to group and report key findings from similar papers. The study was determined to be non-human subjects research by the Michigan State University Institutional Review Board.

We included a total of 18 papers in the FMIG and SRFC review (Table 1). Eleven articles were included describing FMIG (1978 - 2019) 2,4,9-17 and seven describing SRFC (1985-2016).18-24

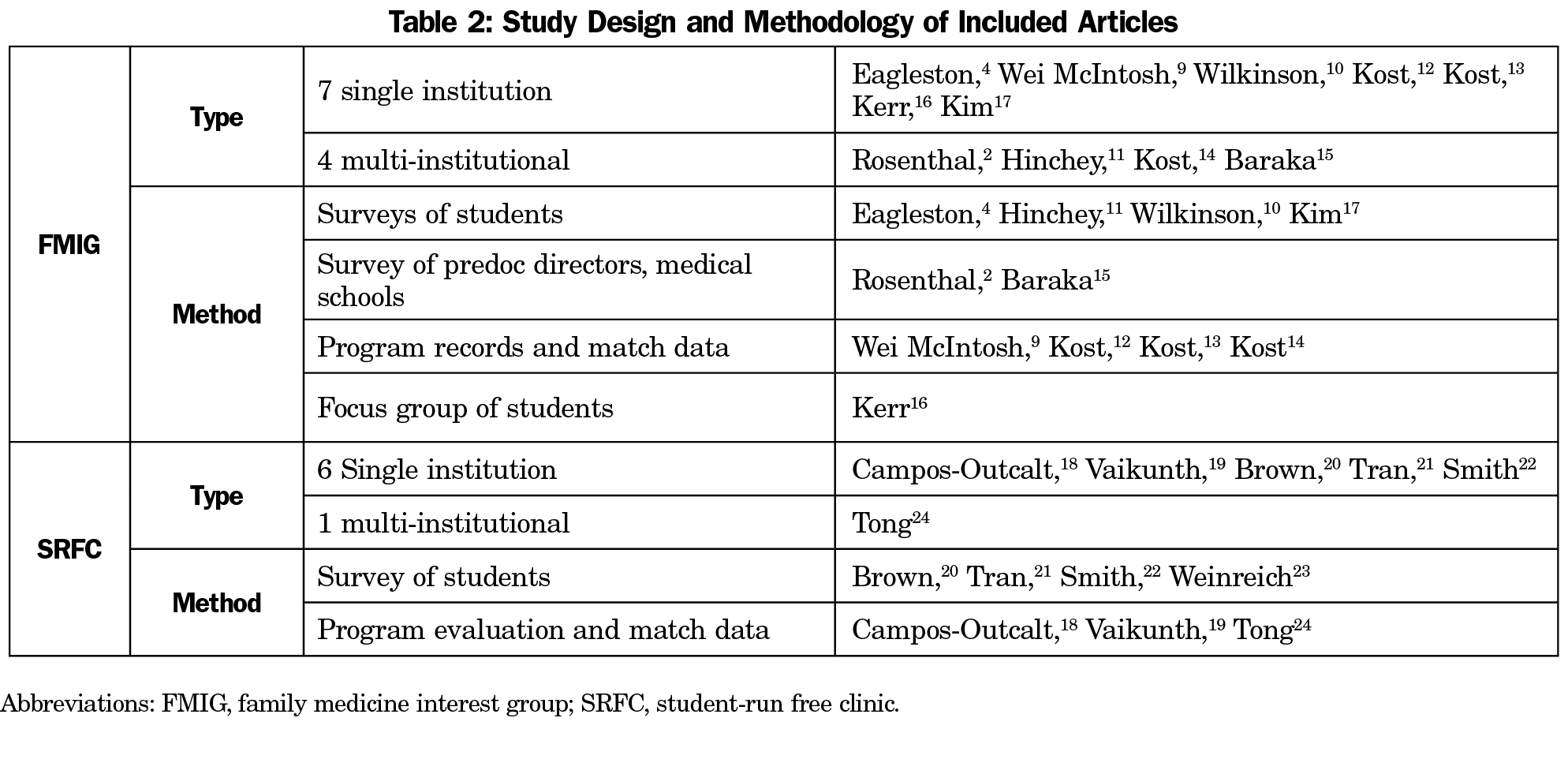

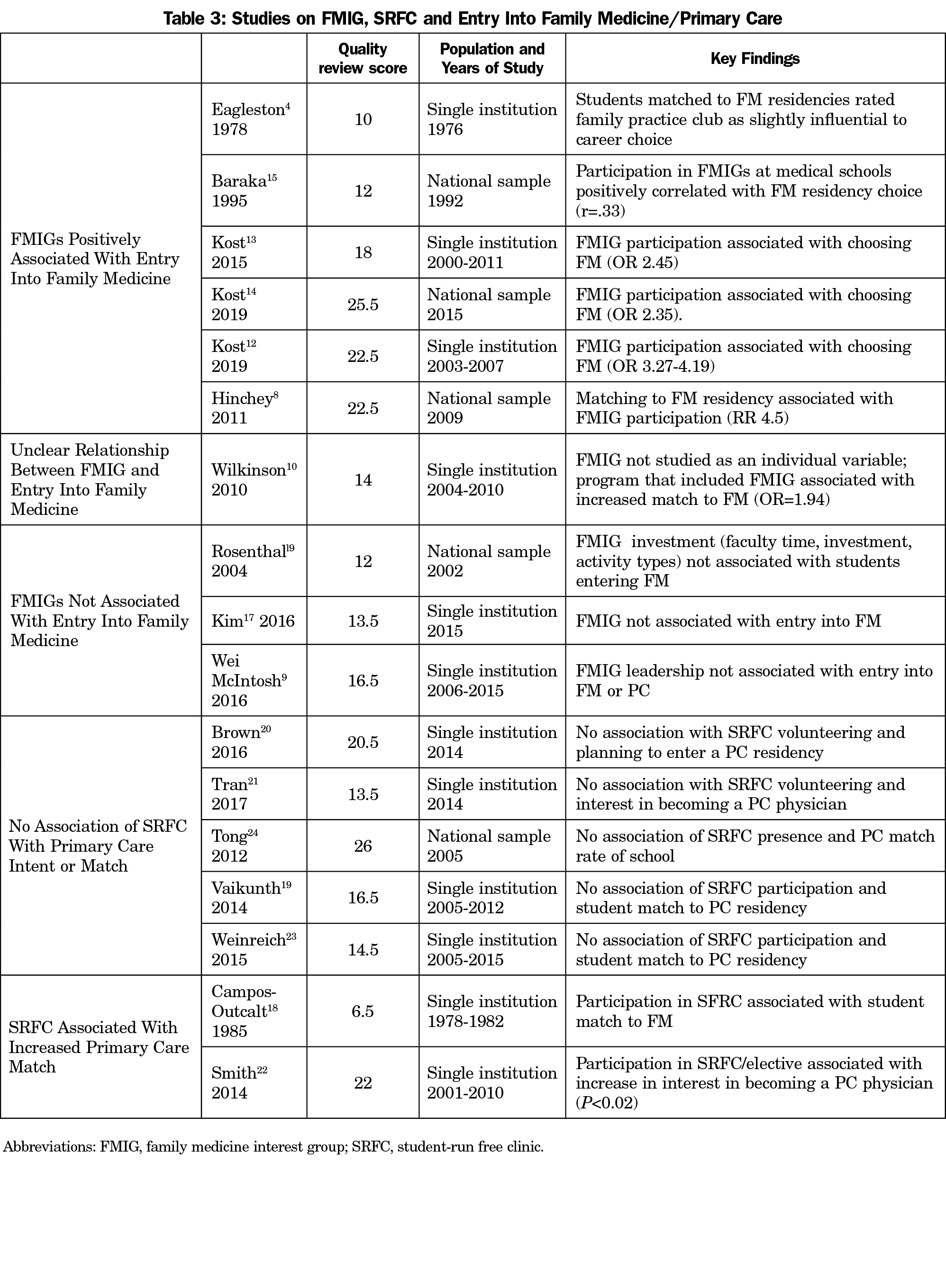

For FMIG, seven were single-institution and four were multi-institutional studies. The first paper published in 1978, termed the program “Family Practice Club,” but otherwise “FMIG” was the shared name for this entity.4 Most were surveys (four student surveys, one predoctoral director survey, and one medical school survey); four used institutional program records and match data, and one was based on a student focus group (Table 2). Ten of the articles were specifically family medicine and FMIG-related, and one article included all specialty student interest groups. For outcomes, 10 examined match data or definitive choice of family medicine as a specialty, and one discussed FMIG effect on specialty interest. Of the nine articles that looked at whether FMIG was associated with entry into family medicine, five papers noted a positive relationship, one paper did not specifically study FMIG as a discrete variable but included FMIG as part of a larger program, and three papers noted that FMIG participation was not associated with entry into family medicine (Table 3).

For SRFC, six were single-institution studies and one was a multi-institutional study. Three studies asked students about increased interest or intent to go into primary care and three articles examined match data (Table 2). Only one paper indicated that SRFC activity correlated with entry into primary care; it was the oldest paper, published in 1985.18

Quality review scores range from 6.5-26, and are included in Table 3. There was no statistically significant difference of quality scores for studies with either positive or negative outcome, when comparing all articles, FMIG articles and SRFC articles.

Although studies have mixed results, most indicate a positive association between FMIG participation and family medicine interest. Several papers measured student-reported interest and intent to consider family medicine as a career instead of using more advanced metrics, such as match and practice data. Only one study examined primary care careers as an outcome. Only one study employed qualitative methodology.16 FMIGs vary widely in their programming, governance, and support, and it is difficult to know what elements of FMIG participation impact student choice. It is not clear whether FMIG participation primarily helps undifferentiated students gain interest in the specialty, or whether it helps support those who already have an established interest in family medicine, though one study concluded that participation can engage both groups of students.12

There were few papers that examined the relationship between participation in SRFC and specialty choice. The literature suggests that SRFC participation does not correlate with entry into primary care. However, a limitation is that most papers were based at a single institution and had lower quality review scores.

Larger-scale and higher quality research are needed to investigate how FMIGs and SRFCs may impact entry into family medicine. An FMIG research network could generate multi-institutional studies. The Society of SRFC could support higher impact scholarly work.25 A national medical student survey through the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) could be used to gather multi-institutional data. Single institutions wishing to examine these issues should consider conducting in-depth, qualitative studies to better understand how FMIGs and SRFCs shape students’ career formation.

Although the literature has limitations, participation in FMIGs is more positively associated with student choice to match to family medicine residencies, while participation in SRFC more consistently lacks an association with matching to primary care residencies. If institutions have limited resources to support student-led activities in primary care with the goal to improve family medicine match rates, this study suggests those resources should be focused on FMIGs.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: This project was partially supported by a grant from the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) Foundation (Dr Julie P. Phillips, PI), and also partially by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number D54HP23297, Academic Administrative Units (Dr Christopher P. Morley, PI). This information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by the ABFM, HRSA, HHS, or the US Government.

Presentations: This study was previously presented as: Kost A, Sairenji T, Phillips JP, Polverento M, Prunuske J, Kovar-Gough I, Morley C. The Impact of Family Medicine Interest Groups on Primary Care Career Choice: A Systematic Review. Completed Research Presentation at STFM Conference on Medical Student Education (virtual). February 2021.

References

- Kelly C, Coutinho AJ, Goldgar C, et al. Collaborating to achieve the optimal family medicine workforce. Fam Med. 02 2019;51(2):149-158. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.926312

- Rosenthal TC, Feeley T, Green C, Manyon A. New research family medicine interest groups impact student interest. Fam Med. 2004 Jul-Aug 2004;36(7):463.

- Join an FMIG. American Academy of Family Physicians. Accessed October 19, 2021. https://www.aafp.org/students-residents/medical-students/fmig.html

- Eagleson BK, Tobolic T. A survey of students who chose family practice residencies. J Fam Pract. 1978;6(1):111-118.

- Functions and Structure of a Medical School-Standards for Accreditation of Medical Education Programs Leading to the MD Degree. Liaison Committee for Medical Eucation. March 2020. Accessed December 30 2021. https://lcme.org/publications/#Guidelines--amp--Procedures

- Phillips RLDM, Petterson S, et al. Specialty and geographic distribution of the physician workforce: what influences medical student and resident choices? The Robert Graham Center; 2009.

- Phillips J, Wendling AL, Young V,et al. Medical school characteristics and practices that support primary care specialty choice: a scoping review. Fam Med. In press.

- Kost A, Phillips J, Polvernto M, Kovar-Gough I, Sairenji T. The influence of role modeling and mentoring on primary care career choice: a narrative synthesis of thirty years of research. Fam Med. In press.

- Wei McIntosh E, Morley CP. Family medicine or primary care residency selection: effects of family medicine interest groups, MD/MPH dual degrees, and rural medical education. Fam Med. 2016;48(5):385-8.

- Wilkinson JE, Hoffman M, Pierce E, Wiecha J. FaMeS: an innovative pipeline program to foster student interest in family medicine. Fam Med. 2010;42(1):28-34.

- Hinchey S, LaRochelle J, Maurer D, Shimeall WT, Durning SJ, DeZee KJ. Association between interest group participation and choice of residency. Fam Med. 2011;43(9):648-652.

- Kost A, Kardonsky K, Cawse-Lucas J, Sairenji T. Association of family medicine interest at matriculation to medical school and FMIG participation with eventual practice as a family physician. Fam Med. 2019;51(8):682-686. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.239373

- Kost A, Cawse-Lucas J, Evans DV, Overstreet F, Andrilla CH, Dobie S. Medical student participation in family medicine department extracurricular experiences and choosing to become a family physician. Fam Med. 2015. 47(10):763-9.

- Kost A, Bentley A, Phillips J, Kelly C, Prunuske J, Morley CP. Graduating medical student perspectives on factors influencing specialty choice: an AAFP national survey. Fam Med. 2019;51(2):129-136.

- Baraka SM, Ebell MH. Family medicine interest groups at US medical schools. Fam Med. 1995;27(7):437-9.

- Kerr JR, Seaton MB, Zimcik H, McCabe J, Feldman K. The impact of interest: how do family medicine interest groups influence medical students? Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(1):78-79.

- Kim G, Mailloux J, Van de Kleut C. Does participation in family medicine interest group events at Canadian medical schools influence residency decisions? University of Western Ontario Medical Journal. 2016;85(2):6-8. doi:10.5206/uwomj.v85i2.2201

- Campos-Outcalt D. Specialties chosen by medical students who participated in a student-run, community-based free clinic. Am J Prev Med. 1985 Jul-Aug 1985;1(4):50-1. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(18)31400-4

- Vaikunth SS, Cesari WA, Norwood KV, et al. Academic achievement and primary care specialty selection of volunteers at a student-run free clinic. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26(2):129-134. doi:10.1080/10401334.2014.883980

- Brown A, Ismail R, Gookin G, Hernandez C, Logan G, Pasarica M. The effect of medical student volunteering in a student-run clinic on specialty choice for residency. Cureus. 2017;9(1):e967. doi:10.7759/cureus.967

- Tran K, Kovalskiy A, Desai A, Imran A, Ismail R, Hernandez C. The effect of volunteering at a student-run free healthcare clinic on medical students’ self-efficacy, comfortableness, attitude, and interest in working with the underserved population and interest in primary care. Cureus. 2017;9(2):e1051. doi:10.7759/cureus.1051

- Smith SD, Yoon R, Johnson ML, Natarajan L, Beck E. The effect of involvement in a student-run free clinic project on attitudes toward the underserved and interest in primary care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25(2):877-889. doi:10.1353/hpu.2014.0083

- Weinreich M, Kafer I, Tahara D, Frishman W. Participants in a medical student-run free clinic and career choice. J Contemp Med Educ. 2015;3(1):6-13. doi:10.5455/jcme.20150321111913

- Tong ST, Phillips RL, Berman R. Is exposure to a student-run clinic associated with future primary care practice? Fam Med. 2012;44(8):579-581.

- Society of Student Run Free Clinics. Accessed June 11, 2021. https://www.studentrunfreeclinics.org/

There are no comments for this article.