Anxiety. Despair. Burnout. Moral Injury? Medical students face varied challenges ranging from increased academic workload to difficult clinical events. Resiliency is the ability to respond to stress in a way that minimizes psychological and physical detriment.1 Promoting resiliency skills among trainees may be an effective method of reducing long-term burnout. While many papers have been published exploring physician burnout, there is little research into stresses facing students during medical training.2,3 Medical students may be less resilient than the general population but are interested in learning resiliency skills.4 Currently, few such programs exist to teach these skills, and their efficacy is largely unknown.

BRIEF REPORTS

Medical Students’ Perceptions and Retention of Skills From Active Resilience Training

Hannah Mugford | Collette O’Connor | Kerry Danelson, PhD | David Popoli, MD

Fam Med. 2022;54(3):213-215.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2022.462706

Background and Objectives: Medical students face difficult transitions throughout their training that increase their risk of burnout. Resiliency training may prepare students to better face the demands of their medical careers. This project is an initial investigation into medical students’ long-term utilization of learned resiliency skills.

Methods: Medical students completed a survey 1-18 months following Active Resilience Training (ART). The computerized survey assessed the program’s success in meeting its stated objectives and how often students used the skills they had learned during the training.

Results: ART is highly effective in increasing awareness of the benefits of resiliency training. The majority of participants would recommend the course to their peers. Students continued to utilize the skills learned for more than 18 months after completing the training. These skills include planned breaks, prioritizing sleep, building support systems, and mindfulness techniques.

Conclusions: This work adds to the existing literature regarding participants’ valuation of novel resilience curricula. Students utilized the skills learned in ART as long as 18 months after completing the program. More study evaluating the specific effects of ART on traditional measures of resilience such as the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) is needed.

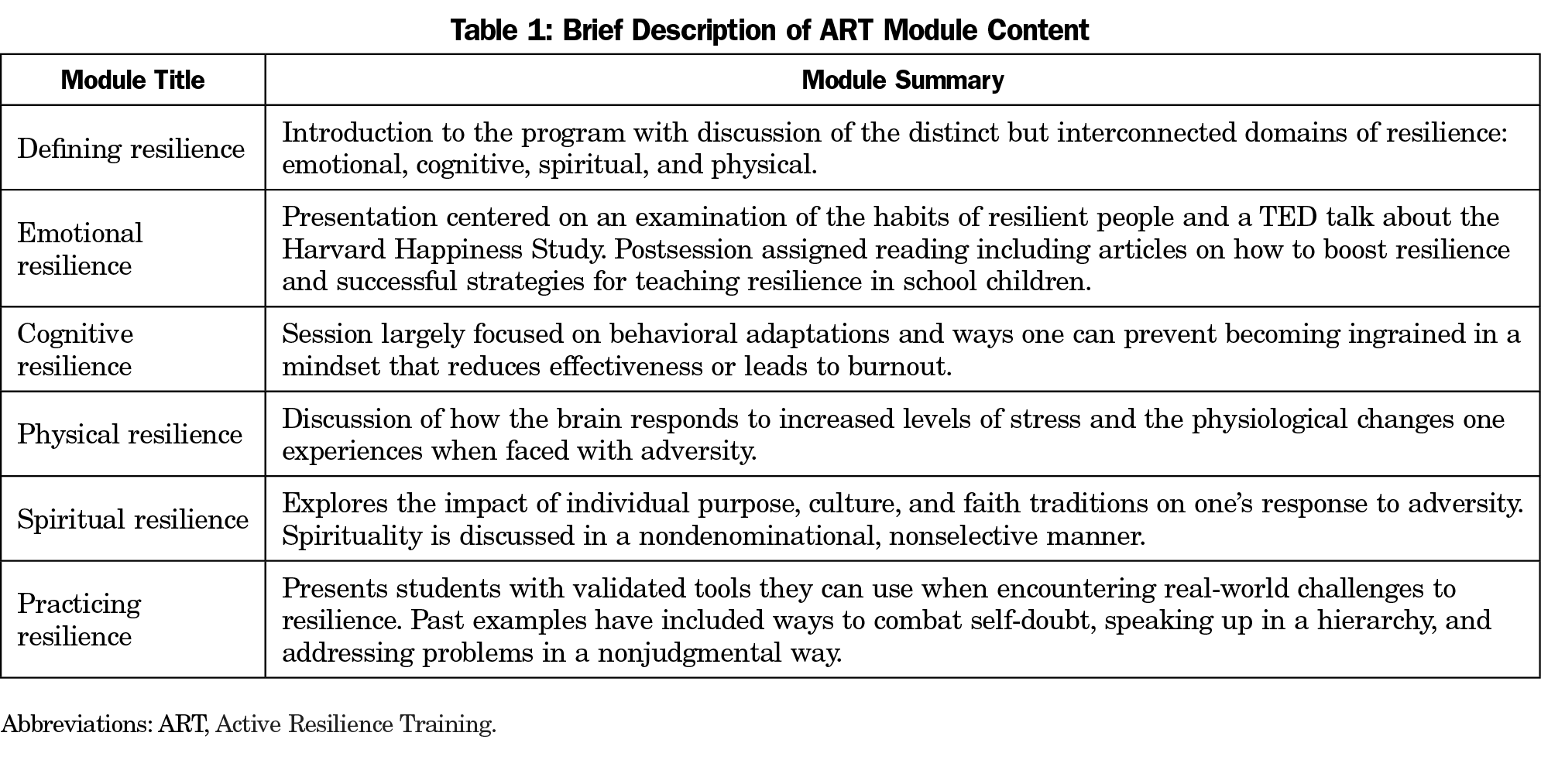

For the past 4 years, Wake Forest School of Medicine (WFSOM) has piloted the Active Resilience Training (ART) in Medicine program. ART is modeled, in part, after the Penn Resiliency Program, which the United States Military has adapted for use.5,6 Each of five modules incorporates prereading and reflection prior to a collaborative presentation between WFSOM faculty and a non-medical speaker. Table 1 includes a summary of each module. At least 1 week later, student facilitators debrief the concepts presented and lead their classmates in discussion on ways to integrate the facets of resilience into their lives.

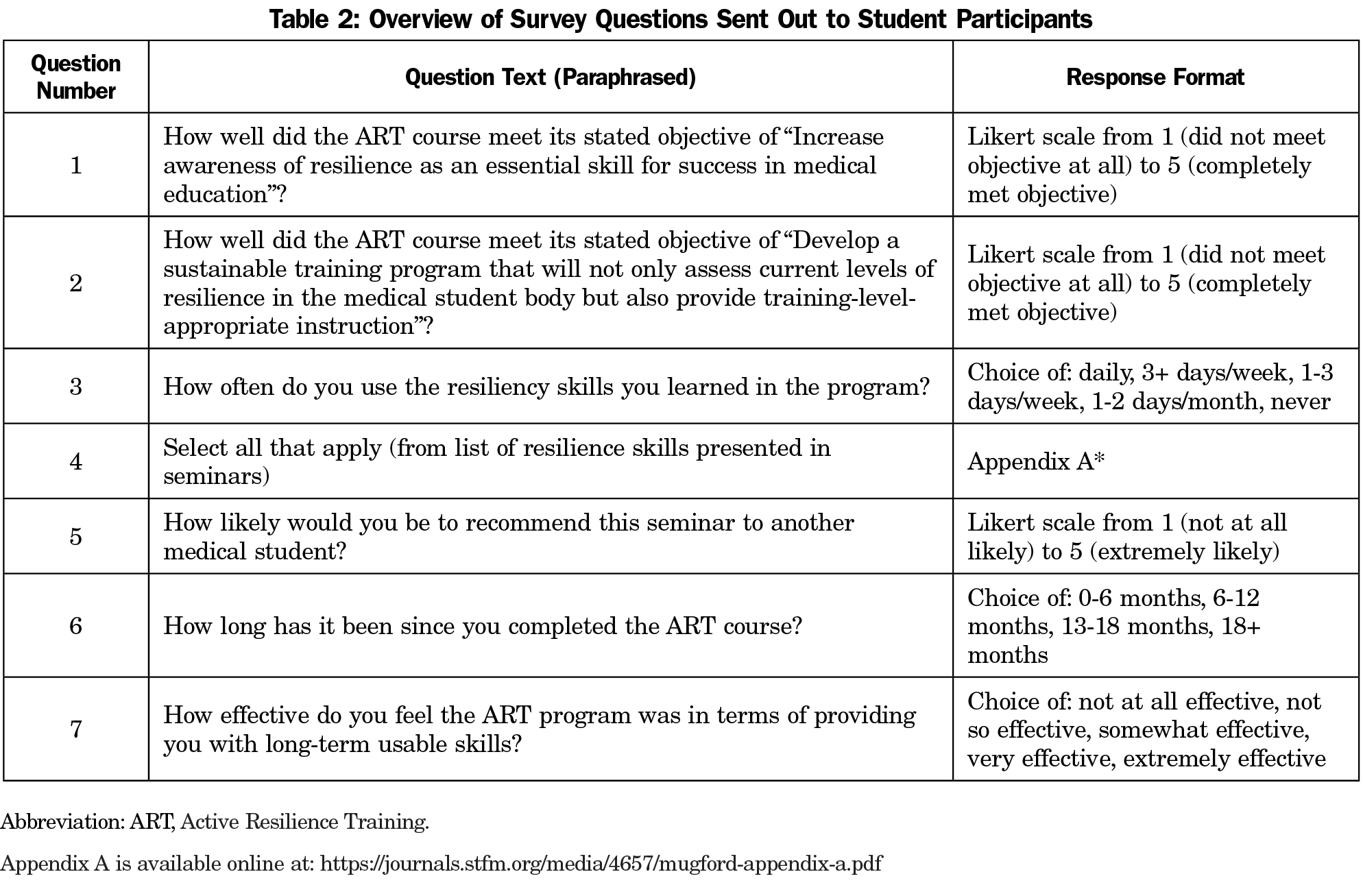

To evaluate the program’s stated objectives and durability of acquired skills, participants completed a 7-question survey 1-18 months after course completion (Table 2). We surveyed 35 students, with an 89% completion rate. The SurveyMonkey Program allowed for three anonymous response types: a continuous slide along a Likert scale of 1 to 5, a choice from provided options, and selection of all that apply. We analyzed all sliding scale responses and categorical variables with descriptive statistics. The Wake Forest University Institutional Review Board granted this study an exemption.

ART was highly effective in meeting its stated objective of “Increase awareness of resilience as an essential skill for success in medical education,” with an average student rating of 91.4%. Additionally, 80.6% of students used the skills they learned from the seminars at least weekly. The remainder of the students used them once or twice per month; 94.4% of the students reported ART was somewhat, very, or extremely effective in instilling long-term usable skills; and 92.7% of participants would recommend ART to another medical student.

The skills most frequently used from ART were planned breaks (83.9%), closer attention to sleep (77.4%), and seeking opportunities to connect with support system (77.4%). Skills not frequently used were meditation techniques with tracing fingers (12.9%) and focused breathing (54.8%).

Overall, participants received this curriculum favorably. Over 90% of students surveyed found ART valuable. This is comparable to Williams et al’s study of a similar elective opportunity for medical students to learn resiliency skills, where 95.8% of participants described the course as “definitely worth it.”7 Other works of resilience curricula in medical education report much lower rates of agreement. Bird et al report a range from 51% to 77% between two institutions in student agreement with resiliency training being a valuable use of time; similar results were reported for a voluntary program conducted for first-year residents.8,9 The degree of variability between studies is likely due to their differing target audiences. Both this study and that by Williams et al included only first- and second-year medical students.7 Bird et al’s studies targeting clerkship students and interns reported lower percent agreement values.8,9 This suggests that earlier exposure to resiliency training improves valuation, perhaps because preclinical students have more time to engage with course material and implement new habits.

Unlike other elective resilience curricula reported to date, this study tracked students’ use of learned skills over time. Prior work examined student benefit from resiliency curricula at course completion, but students answered our survey more than 18 months after finishing ART. Over 1 year after completing the program, a majority of respondents were using what they had learned weekly. Students utilized schedulable activities more frequently. Meditative techniques, consistent with other studies, proved less popular.10

Small sample size was a limiting feature of this initial study. Other studies investigating the benefits of resiliency training feature similarly small sample sizes, with our 89% survey response rate amounting to only 31 students.9 We did not collect data on participant gender, race, or other demographic factors. Bias is also present given enrollment in ART is voluntary, and surveys required participants to accurately self-report their behavior. The enthusiasm students brought to the program may have enhanced their engagement and long-term retention of skills. Self-selection may compound the possibility, necessary to examine in future work, that these results apply to only a subset of medical students rather than the entire group.

Future work could determine whether the skills medical students learn in resiliency courses impact their perceived levels of stress and capability. More rigorous survey questions designed to assess participants’ resiliency and perceived stress before and after completing ART will be included in future iterations of the program. The first ART cohort are now resident physicians, and it remains to be seen whether burnout rates are lower in these individuals compared to their colleagues.

A formal resilience curriculum equips students with skills to navigate the transition points of their medical training and reframe potentially adverse events. Work is needed, however, to address the underlying institutional factors contributing to trainee stress and burnout rather than solely relying on resiliency training to combat their effects.4 The findings of this study will positively inform further development of ART and provide a starting point for other medical schools developing resilience training.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported in part by the Wake Forest School of Medicine.

References

- Seery MD. Resilience: A silver lining to experiencing adverse life events. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2011;20(6):390-394. doi:10.1177/0963721411424740

- Ishak WW, Lederer S, Mandili C, et al. Burnout during residency training: a literature review. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(2):236-242. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-09-00054.1

- Rothenberger DA. Physician burnout and well-being: a systematic review and framework for action. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(6):567-576. doi:10.1097/DCR.0000000000000844

- Houpy JC, Lee WW, Woodruff JN, Pincavage AT. Medical student resilience and stressful clinical events during clinical training. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1320187. doi:10.1080/10872981.2017.1320187

- Penn Resilience Program and Perm Workshops. University of Pennsylvania Department of Arts and Sciences. Accessed September 30, 2021. https://ppc.sas.upenn.edu/services/penn-resilience-training

- Lampkin DR. The Army's Ready and Resilient (R2) Program. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/NCO-Journal/Archives/2019/April/R2-Program/

- Williams MK, Estores IM, Merlo LJ. Promoting resilience in medicine: the effects of a mind-body medicine elective to improve medical student well-being. Glob Adv Health Med. 2020;9:2164956120927367. doi:10.1177/2164956120927367

- Bird A, Tomescu O, Oyola S, Houpy J, Anderson I, Pincavage A. A Curriculum to teach resilience skills to medical students during clinical training. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16(1):10975. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10975

- Bird A, Pincavage A. A curriculum to foster resident resilience. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12(1):10439. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10439

- Danilewitz M, Koszycki D, Maclean H, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of an online mindfulness meditation program for medical students. Can Med Educ J. 2018;9(4):e15-e25. doi:10.36834/cmej.43041

Lead Author

Hannah Mugford

Affiliations: Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC

Co-Authors

Collette O’Connor - Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC

Kerry Danelson, PhD

David Popoli, MD - Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC

Corresponding Author

David Popoli, MD

Correspondence: Bowman Gray Center for Medical Education, 475 Vine St, Winston-Salem, NC 27101.

Email: dpopoli@wake-health.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.