Background and Objectives: Stay-at-home orders, social isolation recommendations, and fear of COVID-19 exposure have led to delays in children’s preventive health services during the pandemic. Delays can lead to missed opportunities for early screening and detection of health problems, and increased risks for outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases. Understanding prevalence of and reasons for missed, delayed, or skipped preventive health services is important for developing strategies to achieve rapid catch-up of essential health services.

Methods: Using the Household Pulse Survey (n=37,064), a large, nationally-representative household survey fielded from April 14 to May 10, 2021, we examined prevalence of households with children who have missed, delayed, or skipped preventive health services, and factors associated with and reasons contributing to missed, delayed, or skipped preventive health services.

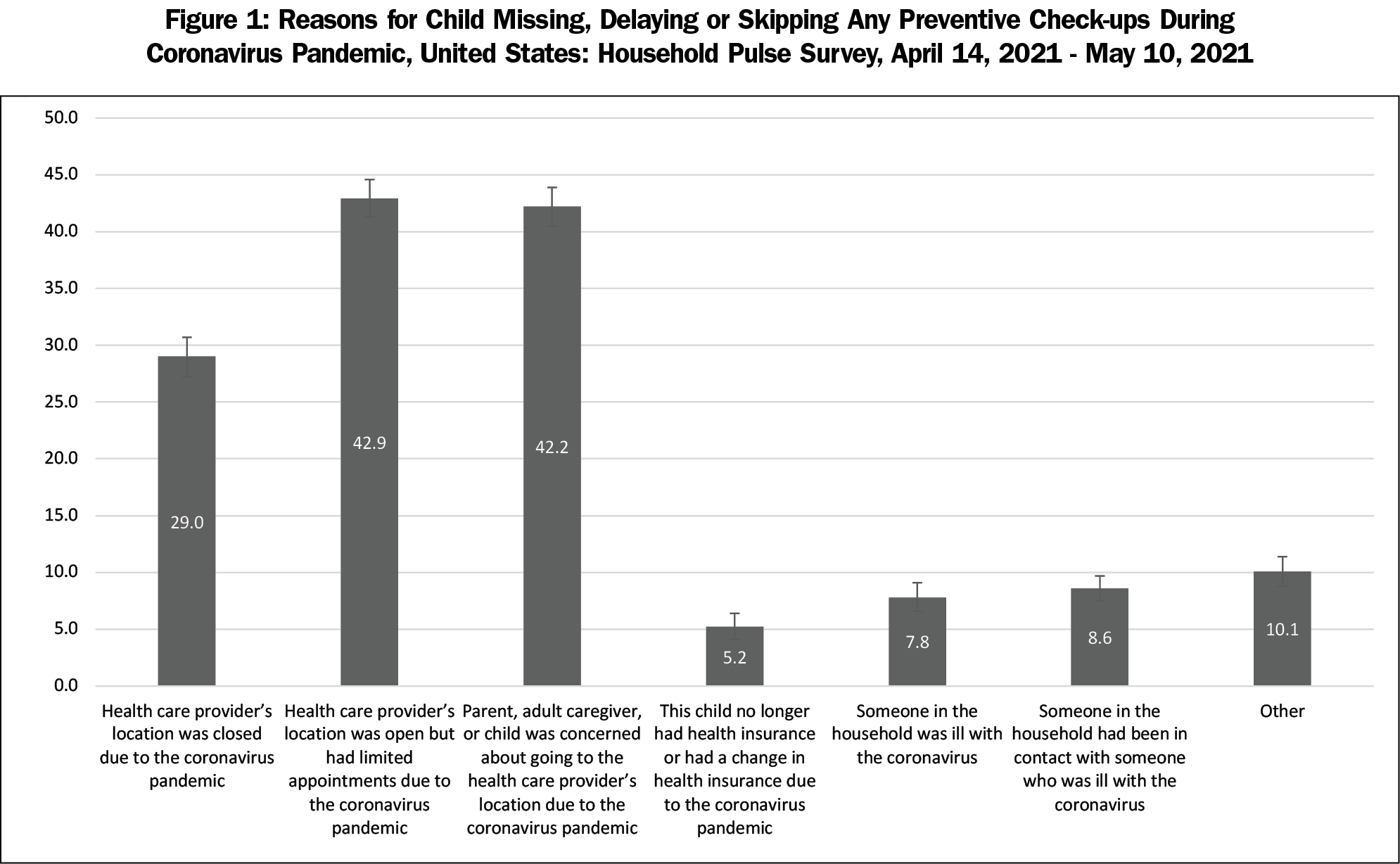

Results: About one-quarter of parents had children who missed, delayed, or skipped preventive check-ups in the past year. Delays in children’s preventive health services were more common among respondents with higher education, households with greater numbers of children, and children who learned remotely or did not participate in formal education. Main reasons attributed to delayed preventive health services were limited appointments at health providers’ offices (42.9%), concern about COVID-19 exposure at health providers’ offices (42.2%), and closed health providers’ offices due to the pandemic (29.0%).

Conclusions: Physician office closures and concern about COVID-19 exposure resulted in over one-quarter of parents delaying preventive services for their children since the pandemic began. Coordinated efforts are needed to achieve rapid catch-up of preventive services and routine vaccines.

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused significant disruptions to health systems and the lives of children and families. In early 2020, as the incidence of COVID-19 cases rose nationally, there were reports of delays in access to emergency medical services and provision of care for non-COVID-related medical problems as well as disruptions in routine preventive and other

nonemergency care.1-4 Several factors contributed to these declines, including social distancing and quarantine policies, such as shelter-in-place and stay-at-home orders to reduce the spread of COVID-19, and concerns regarding risk of exposure in health care facilities.2,5 Delays in getting medical services often led to negative health consequences.6,7

Stay-at-home orders, social isolation recommendations, and fear of COVID-19 exposure also led to decreased accessibility to preventive health services,8 leaving children at risk for poorer health outcomes and vaccine-preventable diseases due to missed opportunities for early screening, detection of health problems, and vaccination.9-13 Children’s preventive health services that cannot be readily conducted through telemedicine (eg, newborn hearing screening, developmental screening, lead screening, vision screening, use of dental care and preventive dental services, and routine vaccinations) prevent detection of conditions and diseases in their earlier, more treatable stages, and significantly reduce the risk of illness, disability, and early death.14,15

The cumulative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s access to preventive health services across the United States, disparities in delays of preventive health services, and reasons for missed, delayed, or skipped appointments are not known. The purpose of this study is to examine prevalence of households with children who have missed, delayed, or skipped preventive health services, and factors associated with and reasons contributing to interruptions in children’s preventive services using a large, nationally representative survey. Understanding disparities caused by delays in children’s preventive health services is important for developing appropriate messages and strategies necessary to achieve rapid catch-up for preventive health services.

Study Design

This study uses data from the Household Pulse Survey (HPS), a large, nationally-representative household survey conducted by the United States Census Bureau since April 2020 to help understand household experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.16 The methodology for this survey has been described previously.16 We combined data from two survey waves (April 14-April 26, 2021 and April 28-May 10, 2021) for this study, with response rates of 6.6% and 7.4%, respectively.17 The sample was restricted to only households with children, for a sample size of 37,064 participants. Of 37,064 respondents who had children living in the household, 10,749 respondents had children who had missed, delayed, or skipped preventive check-ups because of the coronavirus pandemic in the last 12 months. The Tufts University Health Sciences Institutional Review Board reviewed this study and deemed it to be not human subjects research.

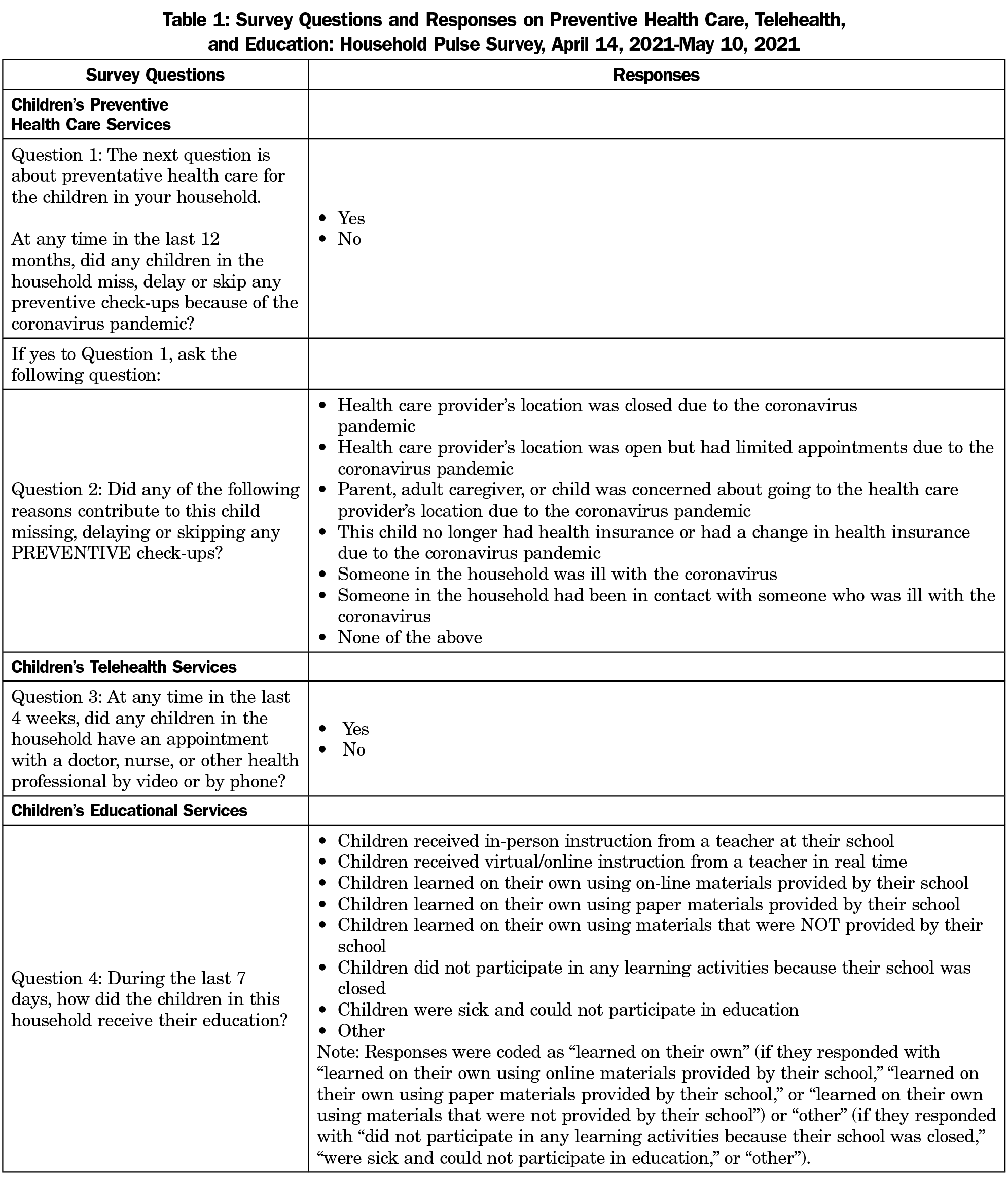

Children’s Medical and Educational Services During Pandemic

Main questions from the HPS used in this study can be found in Table 1. Respondents were asked, “at any time in the last 12 months, did any children in the household miss, delay, or skip any preventive check-ups because of the coronavirus pandemic? (yes/no).” Respondents were not permitted to distinguish among the options of “miss, delay, or skip” in their responses. Although respondents could be any adult in the household, they are referred to as “parents” in this study. Among those who answered yes, parents were asked reasons contributing to the child missing, delaying, or skipping any preventive check-ups.

Children’s telehealth services were assessed by the following question: “at any time in the last 4 weeks, did any children in the household have an appointment with a doctor, nurse, or other health professional by video or by phone? (yes/no).” Children’s educational services were assessed by the question, “During the last 7 days, how did the children in this household receive their education?” Responses, in which parents could select all that apply, were categorized as (1) received in-person instruction from a teacher at their school, (2) received virtual/online instruction from a teacher in real time, (3) learned on their own, or (4) other.

Sociodemographic Variables

Sociodemographic variables describing the parent were age group (18-29, 30-39, 40-49, and ≥50 years), sex (male, female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic [NH] White, NH Black, Hispanic, NH Asian, and NH other/multiple races), educational status (high school or less, some college or college graduate, and above undergraduate education), annual household income (<$35,000; $35,000-$49,999; $50,000-$74,999; ≥$75,000, or not reported), and parent’s insurance status (yes, no). Other variables examined were number of children in the household (1, 2, 3, or more), previous parental COVID-19 diagnosis, and parental COVID-19 vaccination. Previous COVID-19 diagnosis was assessed with the question, “Has a doctor or other health care provider ever told you that you have COVID-19? (yes/no)” COVID-19 vaccination was assessed with the following question: “Have you received a COVID-19 vaccine? (yes/no).”

Analysis

We examined the proportion of children who missed, delayed, or skipped preventive services (hereafter referred to as “delayed”) overall and by sociodemographic factors. Multivariable logistic regression was conducted to examine factors (age group, sex, race/ethnicity, educational status, annual household income, number of children in household, insurance status, reported COVID-19 diagnosis, COVID-19 vaccination status, children’s educational learning modality, and children’s telehealth appointments) that may be associated with delays in children’s preventive services. We examined proportions and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for reasons contributing to delays in children’s preventive services by sociodemographic characteristics. We conducted contrast tests for the differences in proportions, comparing each category to the referent category with a .05 significance level. Analyses accounted for the survey design and replicate weights using balanced replicate weighting procedures in SAS Studio and Stata 16.1 software.17

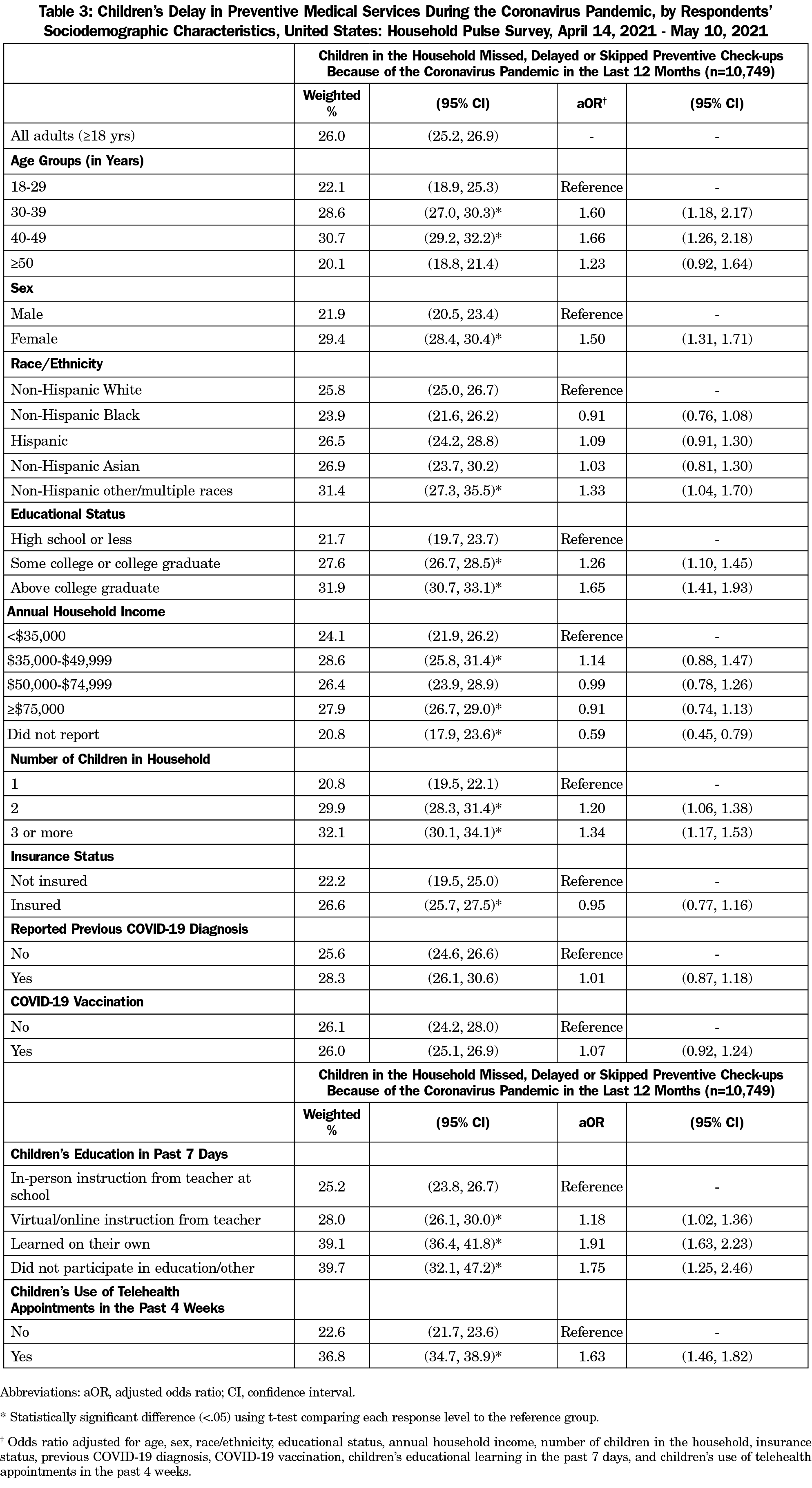

About one-quarter of parents had children who missed, delayed, or skipped preventive check-ups in the past year (Table 2). In unadjusted models, being 18-29, 30-39, or 40-49 years old, female, NH other race, having increasing educational attainment, having increasing number of children in the home, having insurance, having children participate in self-learning or receive no educational instruction, and having children who had telehealth appointments in the previous 4 weeks were associated with higher proportion of delays in preventive health services over the past year compared to their respective counterparts (Table 2).

Similar results were found in adjusted multivariable models (Table 3). For example, delays in children’s preventive health services were more common among respondents who were aged 30-39 years (adjusted odds ratio [aOR=1.60, 95% CI: 1.18-2.17; reference = 18-29 years]), 40-49 years (aOR=1.66, 95% CI: 1.26-2.18; reference = 18-29 years), female (aOR=1.50, 95% CI: 1.31-1.71), and NH other race (aOR=1.33, 95% CI: 1.04-1.70; reference= NH White; Table 3). Respondents who have some college education or a college degree (aOR=1.26, 95% CI: 1.10-1.45) or education beyond a college degree (aOR=1.65, 95% CI: 1.41-1.93) were more likely to have delays than adults with a high school diploma or less. Furthermore, having two (aOR=1.20, 95% CI: 1.06-1.38) or three or more (aOR=1.34, 95% CI: 1.17-1.53) children in the home were associated with a higher likelihood of delays than households with one child. Parents whose children received virtual or online instruction from a teacher (aOR=1.18, 95% CI=1.02-1.36), learned on their own (aOR=1.91, 95% CI: 1.63-2.23), or did not participate in education or had other methods of educational learning (aOR=1.75, 95% CI: 1.25, 2.46) were more likely to have delays. Parents whose children had telehealth appointments in the past 4 weeks (aOR=1.63, 95% CI: 1.46-1.82) were also more likely to have delays in preventive health services over the past year compared to children who did not.

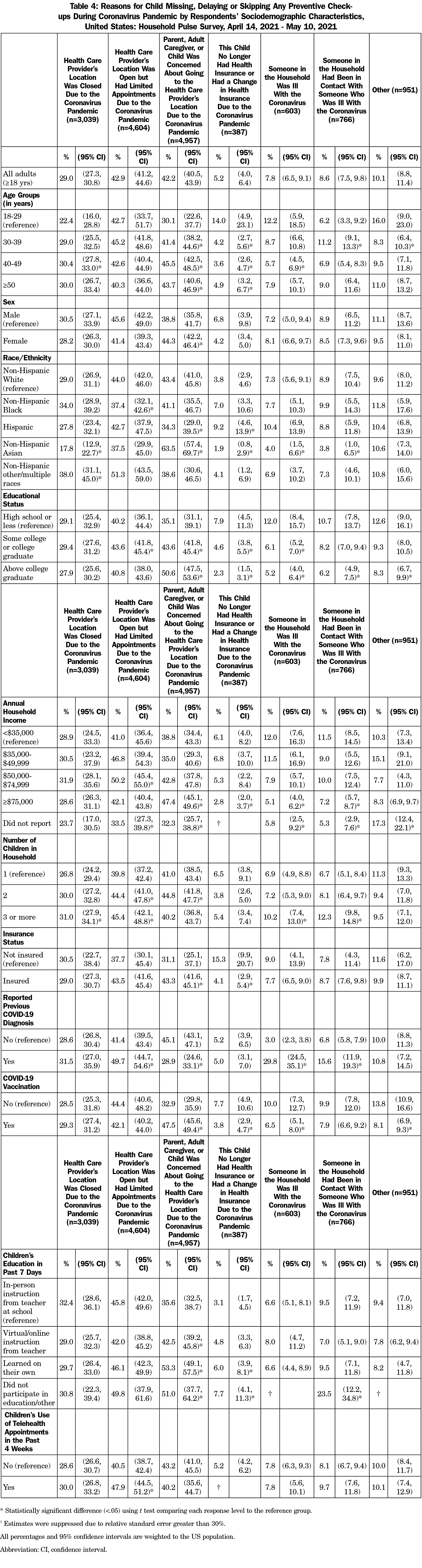

Among all respondents, the most common reasons for delayed children’s preventive health services were limited appointments at health providers’ offices (42.9%), concern about COVID-19 exposure at health providers’ offices (42.2%), and closed offices (29.0%; Table 4 and Figure 1). Concern about exposure to COVID-19 at health providers’ locations were higher among adults age 40-49 (45.5%) compared to adults 18-29 years (30.1%), females (44.3%) compared to males (38.8%), and NH Asian adults (63.5%) compared to NH White adults (43.4%). Adults who were Hispanic (34.3%) or NH other race (38.6%) were less likely than NH White adults (43.4%) to be concerned about going to health providers’ offices. Concern about going to a health providers’ office was more likely among parents who attained education beyond a bachelor’s degree (50.6%) or at least some college (43.6%) versus adults with a high school education or less (35.1%), adults with household incomes ≥$75,000 (47.4%) versus adults with household incomes <$35,000 (38.8%), adults who were insured (43.3%) versus not (31.1%), and parents whose children received any remote education learning or no educational learning in the past 7 days versus parents whose children received in-person instruction from a teacher at school. Lastly, parents who had a previous COVID-19 diagnosis (28.9%) were less likely to be concerned about COVID-19 exposure than parents who never had COVID-19 (45.1%), and parents who received a COVID-19 vaccination (47.5%) were more likely to be concerned about COVID-19 exposure compared to parents who have not received a COVID-19 vaccination (32.9%).

The COVID-19 pandemic caused significant disruptions to children’s and families’ daily lives, including affecting children’s preventive health services. Preliminary data of Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) beneficiaries under 18 years of age showed that primary, preventive, and mental health services declined substantially through April 2020, and were lower in May 2020 than in previous years.9 While service delivery via telehealth for children increased during this time, it was not enough to offset the decline in preventive health services.9 Furthermore, some services, such as screening, dental, immunization and other services, cannot be completed remotely.

Unfortunately, our study found that about 1 in 4 households with children had missed, delayed, or skipped preventive health services during the pandemic. While some of this delay was due to living with someone who was ill with or was in contact with someone who was ill with COVID-19, the main reasons for the delay were limited appointments and fear of exposure to COVID-19 in doctors’ offices. These findings are consistent with previous studies that found reductions in children’s medical care and emergency department visits during the pandemic.1-4 For example, data from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid indicate a decline in services used by children covered by Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) from 2020 compared to the year prior.6 For example, there were 1.7 million (22%) fewer vaccinations for children up to age 2 years, 3.2 million (44%) fewer child screening services, 6.9 million (44%) fewer outpatient mental health services even after accounting for increased telehealth services, and 7.6 million (69%) fewer dental services.

We built on these studies by finding that households with an increasing number of children in the home were more likely to have skipped, missed, or delayed preventive services, suggesting that the proportion of delayed preventive health services among children may be even higher. Delays due to closed doctors’ offices were also higher among adults who were of NH other races compared to NH Whites, while delays due to concerns about COVID-19 exposure were highest among NH Asians compared to NH Whites, suggesting additional efforts are needed to increase catch-up preventive services in these populations. Furthermore, younger parents (those ages 30-39 and 40-49 years) were more likely to have children who missed, delayed, or skipped preventive appointments, possibly due to their likelihood of having younger children than older parents. We also found lower odds of missing, delayed, or skipped appointments among respondents who did not report their incomes. These groups were more likely to be older, and thus, are more likely to have older children, who do not have as many preventive check-ups as younger children.

Children who use telehealth services were more likely to have delays, suggesting that these groups may have reverted to using virtual services due to their delays in preventive check-ups. This is consistent with other studies which found that many provider offices have transitioned to telemedicine practices to provide continuity of care during the pandemic.18 While increases in telehealth services during the pandemic is commended, a study found that the use of telehealth services did not offset the decline in preventive health services, and many services cannot be completed remotely.9 The association found between telehealth appointments and delayed preventive checkups suggests that these families are reluctant to come into health care providers’ offices. This belief is also reinforced by our findings that one of the main reasons for delays in childhood preventive services was concern about COVID-19 exposure at health facilities.

While closures and limited health care provider appointments early in the pandemic may have contributed to parents delaying preventive health services for children, concerns about potential exposure to COVID-19 during well-child visits may have been more likely as the pandemic progressed and the number of COVID-19 cases increased.19 Our findings that delays were greater among parents who had insurance and were highly educated compared to their respective counterparts supports our finding that concerns about potential COVID-19 exposure in health care facilities, rather than access, may be the main cause of these delays. This is further supported by our finding that only 5.2% of parents reported lack of insurance or change in insurance during the pandemic as a reason for missed, skipped, or delayed vaccinations. These populations may be more likely to follow the recommended schedule, and thus, are more likely to know if their child has any missed, skipped, or delayed preventive services.

The CDC recommends that any interrupted immunization services should be resumed and catch-up vaccinations offered as quickly as possible.20 Clinic hours can be extended, and special vaccination events or drive-by vaccination services can be instituted.21, 22 It is also possible to configure clinics and schedules such that COVID patients do not come into contact with others.22 Getting vaccinated for COVID-19 may help alleviate concerns about risk of COVID-19 exposure in health care facilities. With the COVID-19 vaccine now more readily available to all persons aged 12 years and older, parents and age-eligible children, in addition to health care providers and staff, should get vaccinated for COVID-19 to reduce risk of infection and severe health outcomes from COVID-19. Health care providers have the power to effectively recommend vaccination to their patients, and the CDC notes that such a recommendation is the main factor in convincing parents to get vaccinated themselves.21, 22 Given our findings about the use of telemedicine during the pandemic, such visits seem to be an ideal time for clinicians to deliver a vaccination message. Health care providers can help alleviate concerns about COVID-19 exposure by providing safe distancing, good hygiene measures, protective equipment, and assuring parents that infection control practices are in place.22 In addition, health care providers should follow up with parents of children with missed preventive care services and remind parents about the importance of these services in reducing serious health outcomes,23 strengthen clinic reminder systems, and take advantage of any encounter to deliver vaccinations.21 In addition, public health officials should continue monitoring and identifying areas and populations with missed preventive services or low vaccination coverage and enable a rapid public health response.22,23 It is important to give priority to primary series vaccinations such as measles-mumps-rubella and polio, as international experience has shown that falling behind on these can result in outbreaks with substantial morbidity and mortality.22 Johns Hopkins University has guidance for patients trying to decide when to see a physician in person versus virtually, as well as when their children should receive medical services including vaccinations in the context of a pandemic.24

Our findings are subject to several limitations. First, although sampling methods and data weighting were designed to produce nationally representative results, respondents might not be fully representative of the general US adult population.25 Second, the HPS has a low response rate (<10%). However, nonresponse bias assessment conducted by the US Census Bureau found that the survey weights adjusted for most of this bias, even though some bias may remain.25 Third, the HPS is a cross-sectional survey, so temporal relationships cannot be assessed. Fourth, the HPS collects information on adults and not children, thus, characteristics of children (such as age) and collateral impact of delays on children could not be assessed. Fifth, the survey did not define or separate out “missed,” “delayed,” or “skipped” preventive services, which could have different meanings for immunization and screening programs. Furthermore, the survey does not define preventive services, which could lead to overestimation if parents include telemedicine or underestimation if parents do not know what constitutes preventive services. Sixth, parents who follow the recommended children’s preventive health schedules may be more likely to be aware if they have missed, skipped, or delayed appointments. Thus, our results may be underestimated if parents did not follow the recommended schedule and do not consider themselves to be delayed. Additionally, delays may be higher in rural areas; however, the HPS does not contain information on urban/rural status. Finally, vaccination coverage assessment at the state and local level is needed to quantify the impact of the pandemic among children of all ages and prioritize areas for intervention.

Preventive services for many children may have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic due to disruptions in routine medical care and stay-at-home orders, which may increase risks for negative health consequences and outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases. Parental concerns about potentially exposing themselves or their children to COVID-19 during well-child visits might contribute to these delays. Although the delivery of recommended childhood vaccines may have recovered following the initial impact of the pandemic, continued efforts should be made to ensure that children continue receiving preventive services during the pandemic and other emergency situations. Providers can increase preventive care visits by reducing concerns about COVID-19 exposure in the provider’s office, reminding parents of the continued need for preventive services during emergencies, providing parents with timely notices when preventive services are due, and promoting tools to conduct reminders and recalls.23 Continued collaboration between health care providers and public health officials is needed to coordinate efforts and messages to achieve rapid catch-up health service delivery.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: Author Laura Corlin was supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) grant number K12HD092535, and by the Tufts University/Tufts Medical Center COVID-19 Rapid Response Seed Funding Program. The other authors received no external funding.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Lazzerini M, Barbi E, Apicella A, Marchetti F, Cardinale F, Trobia G. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(5):e10-e11. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30108-5

- Wong LE, Hawkins JE, Langness S, Murrell KL, Iris P, Sammann A. Where are all the patients? Addressing covid-19 fear to encourage sick patients to seek emergency care. NEJM Catal. 2020.

- Gavish R, Levinsky Y, Dizitzer Y, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically reduced admissions of children with and without chronic conditions to general paediatric wards. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110(7):2212-2217. doi:10.1111/apa.15792

- Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19–related concerns—united States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1250-1257. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4

- Financial Industry Regulatory Authority. State “shelter-in-place” and “stay-at-home” orders. Washington, DC: Financial Industry Regulatory Authority; 2020. Assessed on March 2, 2021. https://www.finra.org/rules-guidance/key-topics/covid-19/shelter-in-place

- Fact Sheet: Service Use among Medicaid & CHIP Beneficiaries age 18 and Under during COVID-19. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-service-use-among-medicaid-chip-beneficiaries-age-18-and-under-during-covid-19

- Chanchlani N, Buchanan F, Gill PJ. Addressing the indirect effects of COVID-19 on the health of children and young people. CMAJ. 2020;192(32):E921-E927. doi:10.1503/cmaj.201008

- Nelson R. COVID-19 disrupts vaccine delivery. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):546. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30304-2

- Service use among Medicaid & CHIP beneficiaries age 18 and under during COVID-19. CMS. Accessed January 20, 2022. https://www.medicaid.gov/resources-for-states/downloads/medicaid-chip-beneficiaries-18-under-COVID-19-snapshot-data.pdf

- Stephenson J. Sharp drop in routine vaccinations for US children amid COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum. 2020 May 1 (Vol. 1, No. 5, pp. e200608-e200608).

- Santoli JM, Lindley MC, DeSilva MB, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Routine Pediatric Vaccine Ordering and Administration - United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(19):591-593. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6919e2

- Bramer CA, Kimmins LM, Swanson R, et al. Decline in child vaccination coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic—Michigan Care Improvement Registry, May 2016–May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(20):630-631. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6920e1

- Dinleyici EC, Borrow R, Safadi MA, van Damme P, Munoz FM. Vaccines and routine immunization strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;1-8.

- Millions of children not getting recommended preventive care. CDC. Accessed January 20, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/p0910-preventive-care.html

- Preventive care benefits for children. HealthCare.gov. Accessed January 20, 2022. https://www.healthcare.gov/preventive-care-children/

- Fields JF, Hunter-Childs J, Tersine A, Sisson J, Parker E, Velkoff V, Logan C, and Shin H. Design and Operation of the 2020 Household Pulse Survey, 2020. U.S. Census Bureau. Updated July 31, 2020. Assessed September 9, 2021. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/technical-documentation/hhp/2020_HPS_Background.pdf

- Source of the Data and Accuracy of the Estimates for the 2020 Household Pulse Survey. Census Bureau. Accessed May 5, 2022. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/technical-documentation/hhp/Phase3-1_Source_and_Accuracy_Week_30.pdf

- Smith WR, Atala AJ, Terlecki RP, Kelly EE, Matthews CA. Implementation guide for rapid integration of an outpatient telemedicine program during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;231(2):216-222.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.04.030

- Vaccination Guidance During a Pandemic. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Assessed June 10, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pandemic-guidance/index.html

- COVID-19 Vaccines for Children and Teens. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Assessed May 20, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations/adolescents.html

- Saxena S, Skirrow H, Bedford H. Routine vaccination during covid-19 pandemic response. BMJ. 2020;369:m2392. doi:10.1136/bmj.m2392

- Bjork A, Morelli V. Immunization strategies for healthcare practices and providers. Accessed October 19, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/strat.html.

- Szilagyi PG, Albertin C, Humiston SG, et al. A randomized trial of the effect of centralized reminder/recall on immunizations and preventive care visits for adolescents. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(3):204-213. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2013.01.002

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) Information and Updates. John Hopkins Medicine. Accessed January 20, 2022. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/coronavirus/dont-avoid-your-doctor-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic

- Nonresponse Bias Report for the 2020 Household Pulse Survey. Census Bureau. Assessed June 3, 2021. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/technical-documentation/hhp/2020_HPS_NR_Bias_Report-final.pdf

There are no comments for this article.