Background and Objectives: Physicians are increasingly confronted with patients’ interrelated psychosocial and physiological issues. To assist physicians in managing the psychosocial needs of patients, integrated behavioral health (IBH) has become increasingly common. This study was completed in a large, Midwestern family medicine residency program where the authors sought to (1) identify physicians’ perceptions of IBH implementation and areas of needed IBH improvement, and (2) recognize educational needs to be addressed when providing behavioral health training to resident physicians.

Methods: The authors utilized a pre/post design to measure physician perception of access and quality of an integrated behavioral health program. For quantitative data, we performed standard descriptive statistics, likelihood ratio χ2 tests, independent sample t test, and linear mixed-model analysis. For qualitative data, we completed phenomenological analysis, derived from a focus group.

Results: Physician satisfaction with access and quality of behavioral health services significantly improved after the implementation of the IBH (P<.01). Perception of behavioral health management also improved, including the commitment of the residency program to mental health well-being, benefit from consultations with BHPs, and physician ownership of managing patients’ mental health needs. Themes from the focus group indicated a desire for increased communication with BHPs, as well as additional assessment and intervention skills to manage psychiatric disorders.

Conclusions: Family physicians value IBH in supporting patients’ behavioral health treatment, and resident physicians hone behavioral health management skills through collaborating with BHPs and completing behavioral health training. Residencies should increase focus on teaching essential skills in behavioral health management.

Physicians are increasingly confronted with patients’ interrelated psychosocial and physiological health issues.1,2 Unfortunately, many physicians feel inadequately trained to meet the behavioral health needs of their patients.1 Integrated behavioral health (IBH), an approach that allows for behavioral health providers (BHPs) and physicians to collaborate in providing biopsychosocial treatment to patients in primary care residency settings, has arisen as a way to provide the resources and skills to better manage these needs.3,4

Prior studies have shown that IBH is associated with positive patient outcomes, increased treatment effectiveness, reduced costs, and improved physician satisfaction.5-11 IBH improves patients’ attendance rates to follow-up behavioral health appointments.6 Additionally, physicians report that having IBH increases their skills and confidence in managing behavioral health needs, particularly among resident physicians.12 However, literature is just beginning to identify the impact of IBH on resident physician education,13 as well as training competencies for resident physicians to function effectively as a part of IBH.14-16

The aims of this study were to (1) identify physicians’ perceptions of IBH implementation and areas of needed IBH improvement, and (2) recognize educational needs to be addressed when providing behavioral health training to resident physicians. This study was completed within a large Midwestern family medicine residency program.

In spring 2017, a director of behavioral health initiated a year-long, reoccurring integrated behavioral health internship for two marriage and family therapy master’s degree students from a local university. At the beginning of each internship year, prior to interacting with patients, a 2-week orientation was provided in which the BHPs received training on brief therapeutic models of intervention (ie, solution-focused therapy, motivational interviewing, and cognitive behavioral therapy); specific assessment and intervention skills relevant to providing trauma-informed care; an overview of evidenced-based screening tools utilized in primary care; resources on IBH and primary care nomenclature; guidelines for responding to suicidal ideation as well as homicidal ideation; and an overview of psychotropics was provided by a hospital-based pharmacist. Lastly, the BHPs observed and received observation on integrated care and were provided training on documentation within the electronic medical record. Following training, each BHP spent 12 hours per week on integrated care, receiving warm handoffs from physicians. The other 12 hours were spent providing follow-up psychotherapy to primary care patients in 40-minute increments. The director of behavioral health completed 4 hours of integrated care, and 4 hours of follow-up psychotherapy per week. With this implementation, the integrated behavioral health program was transitioning to a fully integrated system.17

Resident physicians worked collaboratively with BHPs in addressing the psychosocial needs of patients. Curbside consultations, warm handoffs, and shared documentation within the electronic medical recorded afforded consistent communication and learning opportunities relevant to behavioral health assessment and intervention. Resident physicians also completed a 2-week behavioral health rotation and attended monthly behavioral health didactic presentations.

To assess the quality, access, and impact of IBH within the residency, both resident physicians and faculty physicians completed a modified Provider Survey.18 This survey included 22 Likert-scale questions and one open-ended question, and was provided in fall 2016 and in fall 2018. We collected preintegration data in fall 2016. We collected the postintegration data in fall 2018. All surveys were anonymous and voluntary. Resident physicians also participated in one of three focus group interviews in fall 2018. Each focus group was comprised of one interviewer and up to 12 resident physicians, for a total of approximately 36 participants. The University of Kansas Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study.

We used a multimethod (quantitative and focus group) approach to collect, analyze, and interpret the data.19-21 We analyzed the content of the focus group responses by researcher (RN) using phenomenological analysis.22 Patterns of commonality provided rich description of the phenomenon. We developed final themes by consensus of all study participants. See Appendix for interview structure.

For the quantitative data, we performed standard descriptive statistics, likelihood ratio χ2 tests, independent sample t test, and linear mixed model analysis to estimate the effect of the IBH expansion. All analysis were 2-sided with a of 0.05.

Quantitative Results

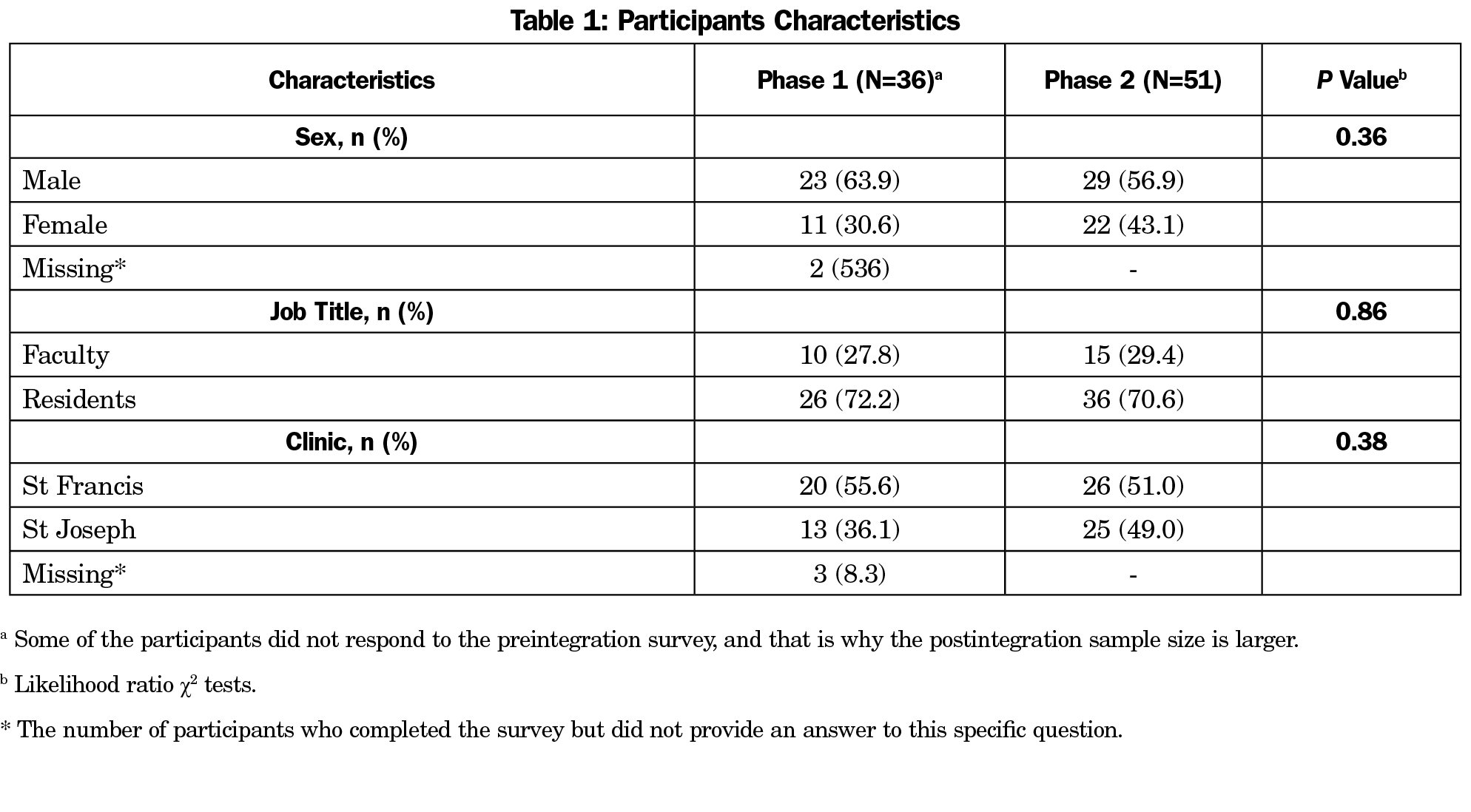

A total of 36 and 51 physicians completed the Phase 1 and Phase 2 surveys, respectively (Table 1). Likelihood ratio χ2 tests showed no significant relationship between participant sex (male vs female), job title, and clinic location.

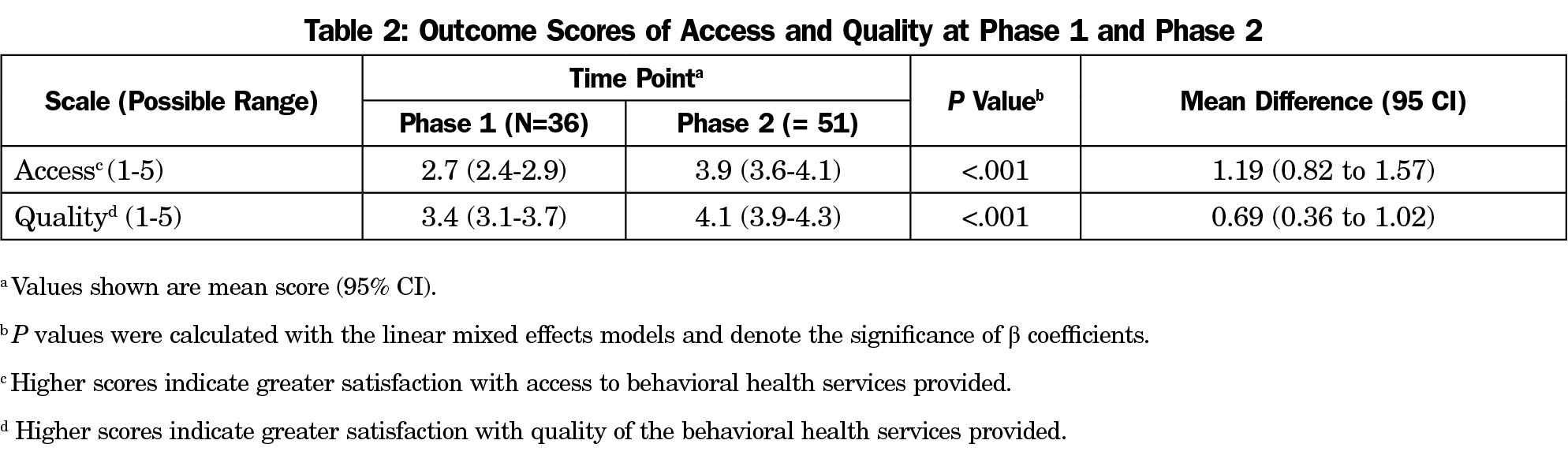

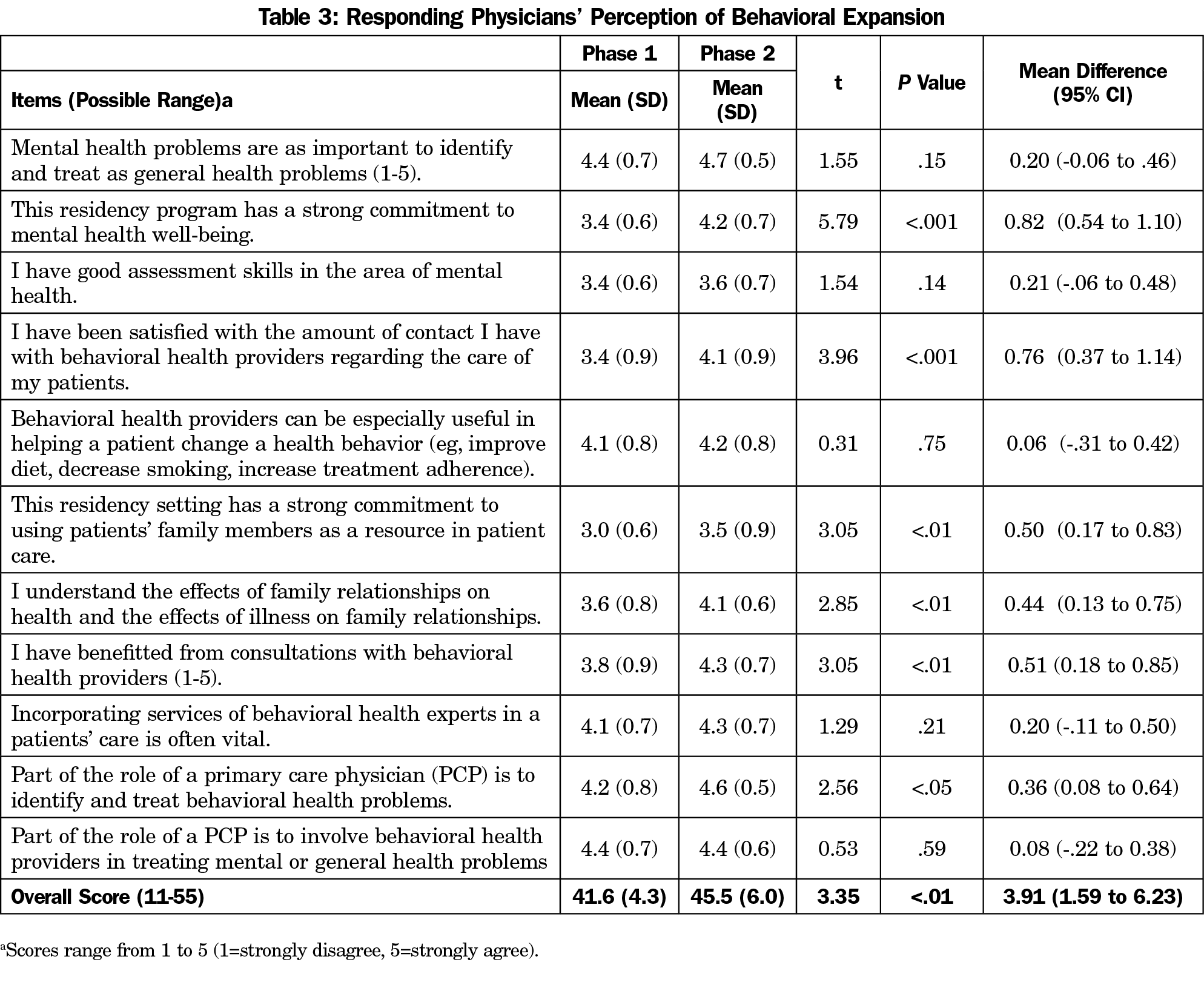

As shown in Table 2, participants’ satisfaction with access and quality of behavioral health services was significantly higher after the implementation of IBH (P<.01). Table 3 summarizes participants’ perceptions of behavioral health management. Overall, the participants’ perception of behavioral health management was significantly higher after IBH, t (85)=3.35, P<.01; 95% CI, 1.59 - 6.23), including commitment of the residency program to behavioral health, benefit from consultations with BHPs, and physician ownership of managing their patients’ behavioral health needs.

Narrative Feedback

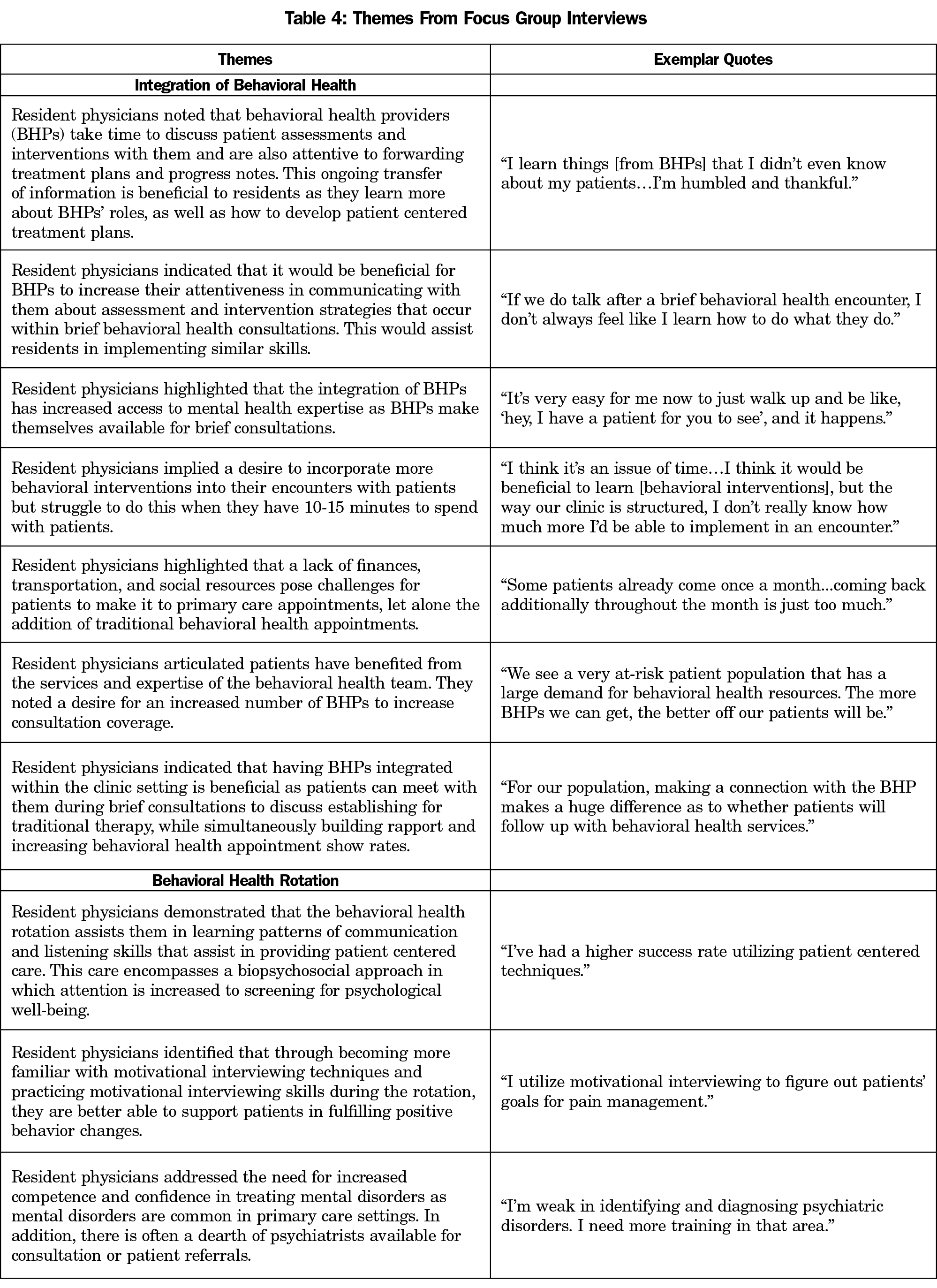

Table 4 provides themes and exemplar quotes that emerged from the focus group interview. The first category of themes related to resident physicians’ perceptions of IBH. Within this category, findings indicated that resident physicians found IBH to be beneficial in providing patients with accessible behavioral health treatment. They also noted that collaborating with BHPs in completing patient consults provided valuable opportunities to hone motivational interviewing and effective communication skills. Further, resident physicians identified specific educational benefit when BHPs were able to share their patient assessment and intervention strategies. Resident physicians did highlight a desire for increased communication with BHPs regarding assessment and intervention strategies, and a need to increase the total number of BHPs within the clinic settings.

The second category identified resident physicians’ perceptions of the required 2-week behavioral health rotation. Resident physicians indicated that the rotation assisted them in learning effective communication and motivational interviewing skills that fostered patient-centered, biopsychosocial care. Resident physicians identified the need for increased training in assessment and intervention of psychiatric disorders.

Our study found that family physicians were significantly satisfied with the access and quality of IBH. Physicians perceived IBH improved their knowledge and skills in managing behavioral health issues, and they increasingly recognized behavioral health management as a part of their fundamental skill set. Further, physicians noted a stronger commitment to behavioral health within the residency program.

Resident physicians perceived that IBH improved patient care. They noted that, through consulting with BHPs and reviewing BHPs’ assessments, they had a deeper understanding of the social and psychological factors impacting patient health. Additionally, resident physicians identified that it was easy to discuss patient care with BHPs, as well as ask for immediate patient consultation if needed. Furthermore, resident physicians noted that patients were more likely to follow up for their behavioral health appointments because they had often met their BHP during a brief intervention, and visits were colocated and often coscheduled at the residency clinic.

The findings from this study parallel current findings related to IBH. Integrated behavioral health improved patient outcomes, increased physician satisfaction, and increased treatment effectiveness. With IBH and training targeted at managing behavioral health disorders, resident physicians are better equipped to manage a myriad of behavioral health disorders within primary care settings.

Our study identified several areas for future improvement in IBH and behavioral health education. First, resident physicians valued BHP’s assessments and skills and desired more transparency in BHP assessments and interventions techniques to improve patient care and their own knowledge. This could be realized by blocking time in resident physicians’ continuity clinics to attend BHP’s brief interventions with their patients. Second, resident physicians noted continual access to BHPs for themselves and patients would be beneficial. Patient access could be further improved by increasing coscheduling of appointments to limit multiple separate visits and transportation barriers. Also, the hiring of full-time BHPs, in addition to BHP interns, would allow for greater continuity of providers, which could in turn foster stronger relationships and increase collaboration. Third, resident physicians indicated that they desired greater competency in assessment and intervention of psychiatric disorders. Providing behavioral health training with increased psychiatric rotations and didactic presentations would assist with this deficit.

There are several limitations to this study. The main limitation is that the pre-and-post datasets were not paired, reducing the ability to draw inference of changes within the group. Second, this study included a single-center, Midwestern family medicine residency setting, and therefore findings may not be generalizable to all programs. Third, the Provider Survey utilized has not been validated.18 Fourth, the retrospective nature of the surveys and focus groups may be prone to recall bias. Lastly, the group think phenomenon may or may not have occurred during the focus group interviews.23,24

In conclusion, family physicians value IBH in supporting patients’ behavioral health treatment, and family medicine resident physicians hone behavioral health management skills both through collaborating with BHPs and completing behavioral health training. This and other family medicine residencies should increase focus on teaching essential skills in behavioral health management. Future areas for research include evaluating the objective impact of IBH and behavioral health training on resident physicians’ knowledge and skills, as well as improvement in patient care.

Acknowledgments

Presentation: The findings from this study were presented in October 2019 at the Collaborative Family Healthcare Association’s Annual Conference in Denver, Colorado.

References

- Bodenheimer T. Primary care--will it survive? N Engl J Med. 2006;355(9):861-864. doi:10.1056/NEJMp068155

- Robinson PJ, Reiter JT, eds. Behavioral consultation and primary care: a guide to integrating services. Springer; 2007. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-32973-4

- McDaniel SH, Hepworth J, Doherty WJ, eds. Medical family therapy: a biopsychosocial approach to families with health problems. Basics Books; 1992.

- Miller BF, Mendenhall TJ, Malik AD. Integrated primary care: an inclusive three-world view through process metrics and empirical discrimination. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2009;16(1):21-30. doi:10.1007/s10880-008-9137-4

- O’Reilly P, Lee SH, O’Sullivan M, Cullen W, Kennedy C, MacFarlane A. Assessing the facilitators and barriers of interdisciplinary teams working in primary care using normalisation process theory: an integrative review. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):1-22.

- Miller-Matero LR, Dykuis KE, Albujoq K, et al. Benefits of integrated behavioral health services: the physician perspective. Fam Syst Health. 2016;34(1):51-55. doi:10.1037/fsh0000182

- Ward MC, Miller BF, Marconi VC, Kaslow NJ, Farber EW. The Role of Behavioral Health in Optimizing Care for Complex Patients in the Primary Care Setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(3):265-267. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3499-8

- Ede V, Okafor M, Kinuthia R, et al. An examination of perceptions in integrated care practice. Community Ment Health J. 2015;51(8):949-961. doi:10.1007/s10597-015-9837-9

- Funderburk JS, Fielder RL, DeMartini KS, Flynn CA. Integrating behavioral health services into a university health center: patient and provider satisfaction. Fam Syst Health. 2012;30(2):130-140. doi:10.1037/a0028378

- Zivin K, Miller BF, Finke B, et al. Behavioral Health and the Comprehensive Primary Care (CPC) Initiative: findings from the 2014 CPC behavioral health survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):612-621. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2562-z

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-576. doi:10.1370/afm.1713

- Hemming P, Hewitt A, Gallo JJ, Kessler R, Levine RB. Residents’ confidence providing primary care with behavioral health integration. Fam Med. 2017;49(5):361-368.

- Hill JM. Behavioral health integration: transforming patient care, medical resident education, and physician effectiveness. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2015;50(1):36-49. doi:10.1177/0091217415592357

- Martin M, Allison L, Banks E, et al. Essential skills for family medicine residents practicing integrated behavioral health: a delphi study. Fam Med. 2019;51(3):227-233. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.743181

- Cronholm PF, Wolk CB. Guidance for Integrated Behavioral Health in Primary Care: Responding to a Proposed Curriculum. Fam Med. 2019;51(8):700-701. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.607155

- Martin MP. Integrated behavioral health training for primary care clinicians: five lessons learned from a negative study. Fam Syst Health. 2017;35(3):352-359. doi:10.1037/fsh0000278

- SAMHSA-HRSA, Center for Integrated Health Solutions. A standard framework for levels of integrated healthcare. Published April 2013. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://www.pcpcc.org/sites/default/files/resources/SAMHSA-HRSA%202013%20Framework%20for%20Levels%20of%20Integrated%20Healthcare.pdf

- Siebel W, Kallenberg G, Patterson J. Provider Survey [Unpublished measurement instrument]. 2014.

- Creswell JW. Mapping the developing landscape of mixed methods research. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, eds. Sage Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research. 2nd ed. Sage; 2010:45-68. doi:10.4135/9781506335193.n2

- Creswell JW, Fetters MD, Ivankova NV. Designing a mixed methods study in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(1):7-12. doi:10.1370/afm.104

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd ed. Sage; 2011.

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches. 2nd ed. SAGE; 2007.

- Aldag RJ, Fuller SR. Beyond fiasco: a reappraisal of the groupthink phenomenon and a new model of group decision processes. Psychol Bull. 1993;113(3):533-552. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.533

- Hogg MA, Hains SC. Friendship and group identification: a new look at the role of cohesiveness in groupthink. Eur J Soc Psychol. 1998;28(3):323-341. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199805/06)28:33.0.CO;2-Y

There are no comments for this article.