Background and Objectives: Residency program directors (PDs) are tasked with supporting resident well-being, and a 2018-2019 CERA survey found PDs to be generally satisfied with residency wellness curricula. However, less is known about graduate medical education wellness programming following the unprecedented social and public health stressors of 2020. This study aimed to evaluate PDs’ satisfaction with wellness programming and perceived changes in wellness program implementation in the context of these factors.

Methods: An online survey was administered by CERA to the program directors of all ACGME-accredited, US-based family medicine residencies. The survey replicated a 2018 CERA survey and assessed PDs’ satisfaction with the wellness curriculum and which wellness curricular elements were currently implemented in the residency.

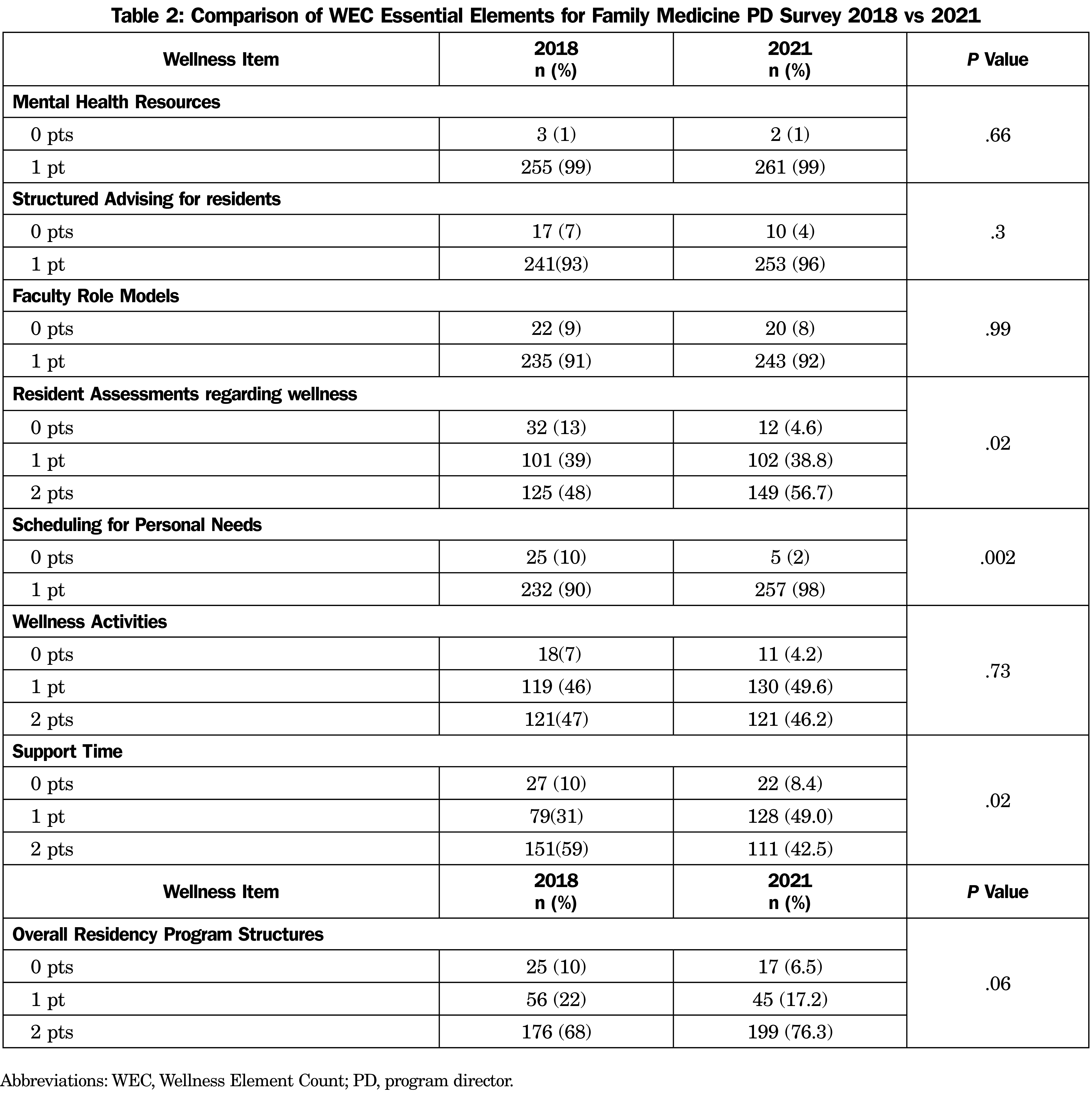

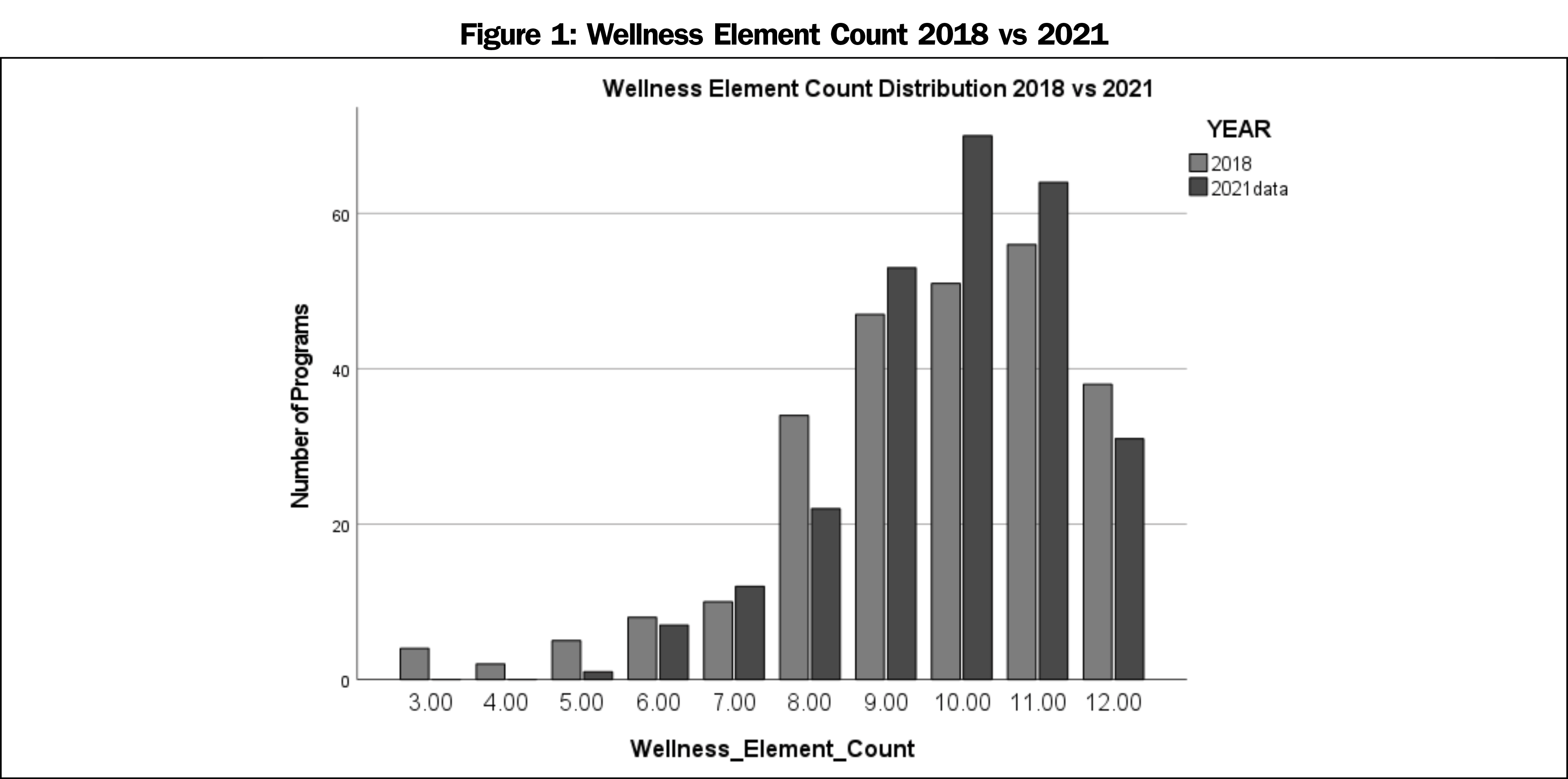

Results: The survey was completed by 263 PDs (42% response rate). There was no difference in total number of wellness curricular elements reported in programs in 2021 (M=9.85) vs 2018 (M=9.57; P=.377). Compared to the 2018 survey, PDs reported increased assessment of resident burnout (P=.02), increased scheduled time for personal needs (P=.002), but decreased scheduled time for interpersonal connection (P=.017). Most PDs reported increased emphasis on wellness and the same or increased access to wellness resources compared to 2018 χ2 indicated no significant difference in PD satisfaction with wellness programming between the two years (P=.84).

Conclusions: Despite significant social and public health challenges to curriculum delivery, family medicine PDs did not perceive significant reductions in wellness programming, and in fact reported increases in some specific curricular elements and an overall increased emphasis on well-being. Future studies should explore the factors that facilitate and impede the implementation of wellness programming.

Supporting resident well-being is a crucial part of program directors’ (PDs) roles. A Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine (FM) PDs indicated satisfaction with resident wellness curricula in 2018.1 For the purposes of this study, “well-being” refers to an outcome, whereas “wellness” refers to elements of a curriculum or culture. Significant sociopolitical and public health stressors in 2020 posed new challenges to graduate medical education (including social isolation, financial strain, safety concerns, etc), threatening resident well-being.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic specifically, residency programs contended with different clinical demands, social distancing, and lost rotation opportunities. Programs experimented with alternate scheduling models for clinical care, virtual didactics and support groups, and enhanced communication about rapidly changing circumstances to maintain supportive learning environments and address resident well-being.2-6 The present study sought to describe differences in PD perception of implementation of essential elements of wellness programming in FM residencies over time. Given the aforementioned challenges, we hypothesized that wellness programming overall and social connection specifically would decrease. A secondary aim was to explore changes in PD satisfaction with wellness programming compared to the previous study.1

Procedures

Our study utilized survey questions developed through previous work guiding resident wellness curricula.1,7 The same online survey methodology as the previous CERA study (conducted December 2018 to January 2019)1,8 was used in this study. The project was approved by the American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board in April 2021. Data were collected from April 14, 2021 to May 17, 2021.

Participants

The study sample was all Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)-accredited US FM residency PDs identified by the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors. The overall response rate was 42.49% (263/619), similar to the previous study.1

Measures

The 10-item survey included the Wellness Element Count (WEC, Table 1) and a question about how PDs perceived access to wellness resources during COVID-19. PDs also were asked how much they agreed with the statement “I am satisfied with my program’s efforts to address resident well-being,” on a 4-point Likert scale. The WEC and satisfaction rating were used in the previous study,1 but the present survey instructed PDs to consider the past year when responding.

Analysis

We assessed bivariate associations using χ2 testing for proportions and Wilcoxon Rank-Sum testing for comparing distributions of wellness elements between 2021 and 2018. We calculated odds ratios using logistic regressions to assess associations between PD satisfaction and programmatic changes since 2018. We conducted analyses using Stata 17 and SPSS software (STATA Corp, College Station, TX).

There was no significant difference (Z=-0.884, P=.377) between overall WEC reported in 2018 (M=9.57) vs 2021 (M=9.85). Figure 1 illustrates the percent of programs by overall WEC in each year. Table 2 outlines the degree to which each essential element was present in 2018 vs 2021. PDs reported significantly less time scheduled for support and connection (either virtually or in person) in 2021 (Z=-2.380, P=.017). They noted increases in assessing resident wellness (Z=2.35, P=.02) and allowing time to schedule personal care (Z=3.13, P=.002).

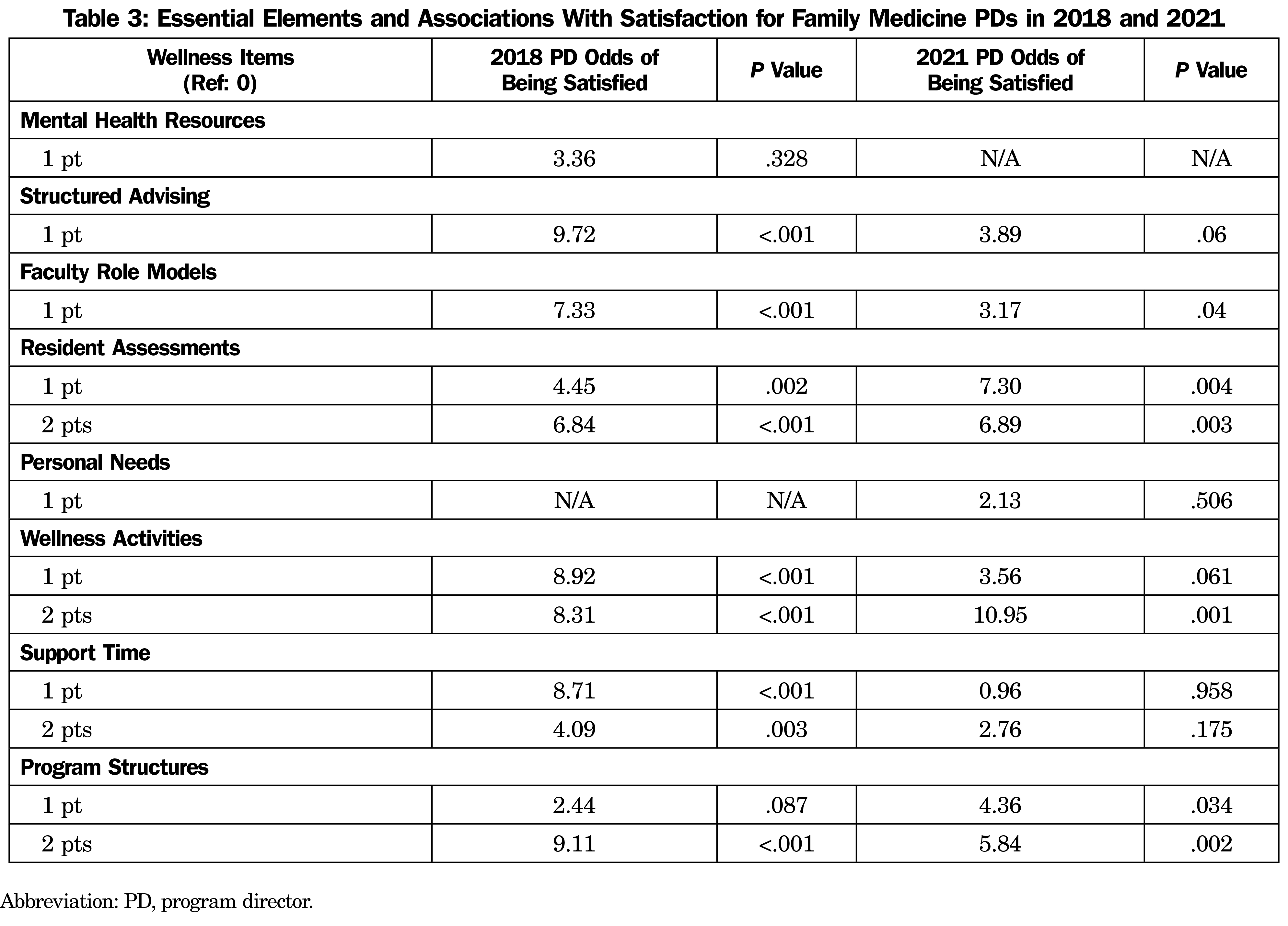

Finally, we hypothesized PDs would report less access to wellness resources in 2020, resulting in lower satisfaction with wellness programming. Most PDs reported increased emphasis (54.6%) on wellness. Access to wellness resources remained the same for 29.8% of programs. Only 15.6% of PDs reported a decrease in resources or less emphasis on wellness. Table 3 presents the results of logistical regression related to the essential elements and PD satisfaction. Overall, there was no significant difference in PD satisfaction between the two survey years (χ2[3, N=520]=0.83, P=.84).

Contrary to our hypothesis, WECs did not seem to decrease, despite the challenges of 2020. In fact, PDs reported significant increases in two essential elements (assessments of resident burnout/well-being and mechanisms for residents to schedule time for personal needs). These reflect ACGME requirements9,10 to regularly assess resident burnout/well-being and to provide time for residents to tend to health and other personal needs. This coincidence fueled our curiosity about the protective role ACGME requirements may play in program wellness. Future research should examine the impact of ACGME well-being requirements on programmatic decisions and the prioritization of resources to support resident wellness.

As hypothesized, time for connection and support decreased during 2021 compared to 2018 data. Our survey does not clarify the reason for this. Social distancing, mask mandates, and virtual learning significantly limited opportunities for social connection and support during the study period. Though the well-being literature emphasizes the importance of social connection and support during residency,11 PD satisfaction was not associated with this essential element. The odds of PD satisfaction increased with greater emphasis on well-being during this period. Future research should explore PD perceptions of the value of the essential elements and barriers to implementation.

Limitations of our study may include the fact that the data presented are cross-sectional, limiting causal associations, the ability to compare responses directly across years, and the opportunity to ask follow-up questions. The data were self-report and potentially limited by various biases, including recall, confirmation, and social desirability. Scale reliability and validity have not been analyzed. Of note, our data represent program director perspectives on the WEC. Thereby, perspectives of other faculty and residents are not captured, which impedes generalizability across programs. While many of the events during 2020-2021 centered on the pandemic, other significant events may have influenced wellness programming. It is possible that nonresponders may have had different experiences with wellness programming in the midst of the pandemic, which are not represented in our data.

In spite of these limitations, our study revealed that important questions remain regarding PD perceptions of the value, barriers, and supports for the identified essential wellness elements, and the impact of ACGME requirements on wellness programing in residencies. Answers to these questions may help guide programs and GME administrators toward more effective promotion of resident well-being.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment: The authors acknowledge Jessica Hauser-Harrington, PhD, for her contributions in conceptualizing this study.

Presentations: Results of this study were presented at the 2022 STFM Annual Spring Conference in Indianapolis, Indiana.

References

- Penwell-Waines L, Cronholm PF, Brennan J, et al. Getting it off the ground: key factors associated with implementation of wellness programs. Fam Med. 2020;52(3):182-188. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.317857

- Hahn TW. Virtual Noon Conferences: providing resident education and wellness during the COVID-19 pandemic. PRiMER Peer-Rev Rep Med Educ Res. 2020;4:17. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2020.364166

- Lie JJ, Huynh C, Scott TM, Karimuddin AA. Optimizing resident wellness during a pandemic: university of British Columbia’s general surgery program’s COVID-19 experience. J Surg Educ. 2020;78(2):366-369. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.07.017

- Lucey CL, Johnston SC. The transformational effects of COVID-19 on medical education. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1033-1034. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.14136

- Colenda CC, Applegate WB, Reifler BV, Blazer DG. COVID-19: financial stress test for academic medical centers. Acad Med. 2020;95(8):1143-1145. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003418

- Byrne LM, Holmboe ES, Kirk LM, Nasca TJ. GME on the frontlines – health impacts of COVID-19 across ACGME-accredited programs. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(1):145-152. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-20-01539.1

- Penwell-Waines L, Runyan C, Kolobova I, et al. Making sense of family medicine resident curricula: A Delphi study of content experts. Fam Med. 2019;51(8):670-676. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.899425

- Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW. Creating a centralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257-260. doi:10.1370/afm.2228

- Wietlisbach LE, Asch DA, Eriksen W, et al. Asch, DA; Eriksen W, Barg FKPhD, Bellini LM; Desai SJ, Yakubu A-R; Shea JA. Dark clouds with silver linings: resident anxieties about COVID-19 coupled with program innovations and increased resident well-being. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(4):515-525. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-20-01497.1

- ACGME Common Program Requirements (Residency). Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2019.pdf

- Southwick SM, Southwick FS. The loss of social connectedness as a major contributor to physician burnout: applying organizational and teamwork principles for prevention and recovery. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(5):449-450. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4800

There are no comments for this article.