Background and Objectives: The goal of this study was to explore how to use sponsoring, coaching, and mentoring (SCM) for faculty development by clarifying the functions embedded in SCM. The study aims to ensure that department chairs can be intentional in providing those functions and/or playing those roles for the benefit of all their faculty.

Methods: We used qualitative, semistructured interviews in this study. We followed a purposeful sampling strategy to recruit a diverse sample of family medicine department chairs across the United States. Participants were asked about their experiences receiving and providing sponsoring, coaching, and mentoring. We iteratively coded audio recorded and transcribed interviews for content and themes.

Results: We interviewed 20 participants between December 2020 and May 2021 to identify actions associated with sponsoring, coaching, and mentoring. Participants identified six main actions sponsors perform. These actions are identifying opportunities, recognizing an individual’s strengths, encouraging opportunity-seeking, offering tangible support, optimizing candidacy, nominating as a candidate, and promising support. In contrast, they identified seven main actions a coach performs. These are clarifying, advising, giving resources, performing critical appraisals, giving feedback, reflecting, and scaffolding (ie, providing support while learning). Finally, participants identified six main actions the mentors perform. The list includes checking in, listening, sharing wisdom, directing, supporting, and collaborating.

Conclusions: We present SCM as an identifiable series of actions that need to be thought of and performed intentionally. Our clarification will help leaders purposefully select their actions and allows opportunity for evaluating their effectiveness. Future research will explore developing and evaluating programs that support learning how to provide SCM in order to enhance the process of faculty development and provide it equitably.

Developing future leaders in health care involves the intentional support of current leaders. 1 This support is provided in part through mentoring, coaching, and sponsoring—three interrelated but distinct processes essential for developing health care leaders throughout their careers. 1 The intentional use of these tools is important to diversify leadership and support future leaders of every underrepresented minority, whether by race, gender, sexual identity, language, disability, or other characteristics. 1-5 While earlier literature often studied these three topics separately, interest has increased in studying them together, clarifying where they overlap and how they are distinct, with the aim of improving the application of these strategies as complementary developmental tools. 1, 2, 6-8

Based on the existing literature, mentoring is broadly viewed as a longitudinal process that guides personal and professional growth through ongoing dialogue. 1, 9, 10 By contrast, coaching is typically periodic, iterative instruction that focuses primarily on concrete technical skills. 1, 11, 12 Conversely, sponsoring involves an episodic act of specific advocacy designed to help advance a career. 1, 10, 13

When examining these tools, it is instructive to focus on the experiences of department chairs since chairs are generally senior leaders in a department, have gone through many career development phases themselves, and developing junior faculty is considered a core task of their position. Despite the importance of these faculty development tools for chairs and departments, most chairs assume their role with little formal training. 14-16 This lack of training and awareness can hinder the development of faculty, and prompts the clarification of the meaning and impact of sponsoring, coaching, and mentoring (SCM) for academic advancement.

The limited diversity among department chairs in family medicine prompted the Council of Academic Family Medicine to create a task force to describe concrete steps for leadership advancement in the discipline. This task force was cochaired by one of the authors (J.E.S.P.). The resultant published findings revealed the importance of someone in an SCM role identifying, directing, and supporting opportunities for underrepresented faculty, because many of these opportunities were not overtly or equitably marketed. 17 Specific career opportunities that could benefit from SCM actions can emerge differently among diverse faculty. Thus, outlining the process for department chairs to implement SCM functions is a necessity for furthering leadership advancement for underrepresented faculty members.

In prior research, we conducted a survey of family medicine department chairs where most indicated that mentoring played a significant role in their career development, with fewer reporting coaching and sponsorship playing significant roles in their advancement. 8 To develop faculty, more respondents reported frequent use of mentoring rather than coaching or sponsoring. 8 It was difficult to ascertain the validity of the results when recognizing the historical dominance of mentoring in the literature.

At the same time, coaching has become relevant in recent decades, while sponsoring has become more visible in the medical literature only in recent years. 1, 7, 8, 11, 13 It can be expected that, because chairs are at the peak of the leadership path, they have taken leadership opportunities made available to them over time and are in a position to regularly sponsor others for such leadership opportunities. Further, it would be expected that chairs provide direction and guidance (elements of coaching) on a day-to-day basis more often than they provide continued career advice (ie, mentoring), leaving that task to senior faculty in their institutions.

We believe the variations in reporting may reflect lack of clarity around the concepts and their use. Papers that clarify the how-to of these elements often include valuable recommendations and guiding principles, and best practices are often based on expert opinion. 1, 2 However, there is a lack of empirical work examining how the tools are applied. The goal of this study was to explore how to use SCM for faculty development by clarifying the functions embedded in SCM to ensure that department chairs can be intentional in providing those functions and/or playing those roles for the benefit of all their faculty.

Exploring the how-to and focusing on the actions relevant to each of these faculty development tools allows individuals to perform the actions more effectively. Further, it empowers individuals to seek these elements of career support, evaluate their experience, and subsequently optimize their involvement. Clarifying the steps for engaging sponsors, coaches, and mentors can increase access to these important professional advancement roles for those who are potential leaders and might otherwise have limited guidance in their careers.

We used qualitative semistructured interviews in this study. Two researchers (M.A. and T.R.) completed interviews from December 2020 through May 2021 with chairs of departments of family medicine at medical schools in the United States. We followed a purposeful sampling strategy building on the connections and relationships of the other three researchers (J.E.S.P., D.S., A.W.) with most of the family medicine department chairs across the country to maximize participant diversification by race, gender, sexual orientation, type of institution, and years in the position.

Our diverse backgrounds helped build a space for critical reflection. Investigator expertise and positions were complementary. M.A., who led the project, is a family physician with a PhD in research methodology. J.S.P. served as a department chair for more than 25 years in two institutions and has served on the faculty of a national leadership program for minority health science faculty for more than 3 decades. D.S. has served as a department chair for 2 years. T.R. is a family medicine faculty member, and A.W. is a researcher who serves as the executive director of the Association of Departments of Family Medicine and has worked with department chairs for 10 years.

We used an operational definition for the construct of SCM based on our literature review.8 We shared the definition with participants at the start of the interview. We defined “sponsoring” as an episodic action in which an individual provides help with career advancement of someone else. We defined coaching as a “periodic and focused instruction, often iterative in nature, following an ‘observe, provide feedback, re-observe’ process for the coach, to help with skill improvement.” Finally, we defined “mentoring” as a longitudinal process aimed at career development through dialogue-based guidance. 8

Table 1 presents the defining terms shared with participants in the interviews. Participants were asked about their experiences receiving and providing SCM, with follow-up prompts to clarify the when, what, whom, how, and why about the experience.

|

|

Sponsoring

|

Coaching

|

Mentoring

|

|

Time frame

|

Episodic

|

Periodic

|

Longitudinal

|

|

Goal

|

Career advancement

|

Skill improvement

|

Career guidance

|

|

Method

|

Specific advocacy

|

Focused instruction

|

Broad-based dialogue

|

We collected basic demographics of participants. We piloted the interview guides with the members of our team, who are a chair (D.S.) and chair emerita (J.S.P.), and revised the questions and flow based on their feedback. The final interview guide is available in Appendix 1. The University of Washington Institutional Review Board approved the study (reference number: STUDY00011949).

M.A. and T.R. conducted interviews via the Zoom videoconferencing platform. We audio recorded and transcribed all interviews. Four study team members (M.A., J.S.P., D.S., T.R.) reviewed the transcripts and provided peer debriefing for the coding done by M.A. using NVivo 11 Pro qualitative software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia). The study team met for 1 hour per week to develop the protocol, revise the interview guide, reflect on interviews, and conduct the analysis.

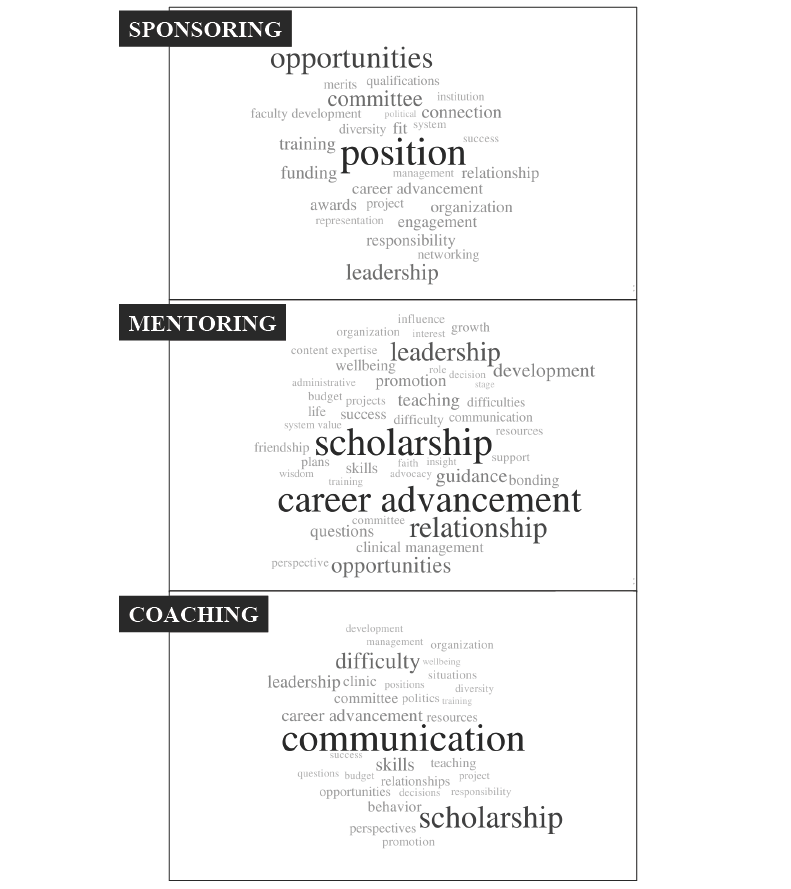

M.A. first coded every reported experience into one of six categories: receiving mentoring, providing mentoring, receiving coaching, providing coaching, receiving sponsoring, and providing sponsoring. The group reviewed the coding. The coded excerpts were thematically explored with input from J.S.P., D.S., and T.R. to show the concrete actions taking place (eg, providing advice, offering help, giving feedback). These concrete actions were then organized in an iterative process within broader categories. Constructs representing and summarizing the categories of related actions were then developed to clarify the how-to of SCM. To name the topic areas and content of each activity involved in SCM, we used in vivo coding (ie, capturing the word as said). We grouped the topic areas into more inclusive categories and developed word clouds to visually present the results. We included supportive quotes to represent each construct. With help from T.R. and input from M.A., J.S.P., and D.S., A.W. reviewed every quote and edited them down for brevity and clarity.

We interviewed 20 participants; demographic characteristics are shown in Table 2. Participants identified how to use SCM. They also indicated the variety of topics and content that SCM encompasses. In what follows, we present the how-to of coaching, mentoring, and sponsorship, with illustrative quotes for each of the SCM main actions included in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4. The word clouds describe the content and topics for SCM in Figure 1.

|

Demographic

|

N (%)

|

|

Age Group (in Years)

|

|

|

40-49

|

1 (5)

|

|

50-59

|

7 (35)

|

|

60-69

|

11 (55)

|

|

70-79

|

1 (5)

|

|

Gender

|

|

|

Male

|

11 (55)

|

|

Female

|

9 (45)

|

|

Sexual Orientation

|

|

|

Straight

|

18 (90)

|

|

LGBTQ

|

2 (10)

|

|

Race

|

|

|

White

|

10 (50)

|

|

Black

|

7 (35)

|

|

Others (Asian or mixed race)

|

3 (15)

|

|

Ethnicity

|

|

|

Hispanic

|

2 (10)

|

|

Non-Hispanic

|

18 (90)

|

|

Years as Chair

|

|

|

< 5 years

|

10 (50)

|

|

> 5 years

|

10 (50)

|

|

Identifying Opportunities

|

|

“But rather than firing people, for most of the time, I found them other positions. I helped them transfer into a role that they like better and they would [find] more fulfilling.” (118)

“I thought she had a skill set that was really valuable to the institution but she technically did not meet the qualifications. So I said to her, ‘Why would not you to apply anyway? And what I am going to do is write to the associate Dean recruiting this position and explain to them that why I think you bring some unique qualifications that would be a real strength to the institution in this position. And that I strongly encouraged her to apply because I did not want [them to think] she did not read the basic qualifications.’” (103)

|

|

Recognizing an individual’s strengths:

|

|

“The most important part of sponsorship is telling somebody that they can be successful because if no one has told them that they can be successful at this level or can accomplish X, then they would not even try. And so often, the first step towards sponsorship is making someone aware that this is something that is attainable.” (105)

“He recently invited me to be a part of a publication for the [state] Academy of Family Physicians about leadership and what it's like to lead teams and I was like, ‘Really? You want me to do that? Why pick me?’ [he was] trying to be more inclusive of the diversity of thought and not saying, ‘I want you to do it because you're a woman or because you're a person of color. I want you to do it because I want to bring your information to the table from your lens of who you are.’ So that's pretty cool.” (120)

|

|

Encouraging Opportunity Seeking

|

|

“If I see opportunities, I will actually go to the people on my list and say, ‘Hey, did you see this? Are you interested in doing it? I would love to talk to you about it. How can I support your application?’” (111)

“Then he would describe a particular position. He would say, ‘I am sitting on a committee. They are looking for X. And I believe you have the skills to fulfill that role. And, by the way, I have already given them your name and phone number. So when they call you say yes.” (116)

|

|

Offering Tangible Support

|

|

“I think a difference in the chair role is that I have a little bit more say sometimes in how the money moves. There are some faculty that have been able to say, ‘Hey, let us go into this strategic fund that I have here. What you are asking is important enough for you and the department that we are going to pay to send you to this particular session or this particular course.’”

(112) “Once I got settled and I was looking for leadership opportunities, I basically found a way to protect part of his time paying salary so that he could become a leader. Basically, he is the champion of quality improvement and our Epic champion.” (109)

|

|

Optimizing Candidacy

|

|

“There was a call for papers and they wanted somebody to write on a topic. And I knew the person leading that project and I said, ‘Hey, I have got someone that I will vouch that they will do a good job. I will give him a little mentorship on this end to make to kind of check in with them, but would it be okay if I gave you her number [and] put her in contact with you for this project?’” (112)

“‘There is a committee that they are asking me for names for and I am going to put your name on that.’ And my immediate reaction was like, ‘Oh, great. Another committee for me...’ But I did not understand until I had done it, that it was the people I would meet, the relationships I would develop, those connections, how it was furthering... it helps you to know where do I get more information in this organization and expertise to help drive initiatives and things that we are working on.” (104)

|

|

Nominating as a Candidate

|

|

“He asked me for more [names] but I only gave him one. There were some other people who wanted to do it that I knew but I did not think that there was really anybody who do it as well as she would do it and she has actually done a great job so far.” (106)

“Before that person announced she was leaving, I was already talking about the merits of the person that I was sponsoring. That she done a great job for our department, we had excellent results. She managed multiple problems, and she was just excellent at what she was doing. So kind of pre-empted. What I knew was going to happen eventually if the other person leaving.” (110)

|

|

Promising Support

|

|

“Once you get past that barrier then you can show them how to put together a package. You can make phone calls on their behalf, you can write letters of recommendation, and you could even be like a mentor. So, you can say that ‘If you accept Dr Smith into your fellowship, I will be available to Dr Smith to continue to work with him, watch him grow, and be invested in his success.’ And sometimes, having a senior person insinuate themselves into a decision process like that can make the difference in whether or not somebody gets chosen.” (105)

|

|

Explaining

|

|

“An example is a [graduate of] our program who was interested in becoming a faculty, we talked about how that could be arranged. For instance, we went to local hospital foundation to fund the fellowship, and talked about how to write the letter, who she needed to get some support from, how to raise it to get the best results, and she got it.”(110)

“And so we talked about what that looks like and how we talk to people and how we set boundaries … And what does that look like and how we can say that to someone without putting ourselves in a bad position.” (114)

|

|

Advising

|

|

“He explained, ‘If you want to achieve X Y or Z, here's how you can do that in an efficient way. If you want to be a member of some committee, the first year, just go to the meeting and sit in the back and listen. And then next year show up and volunteer to do something and then do a good job with it. By the third year, you'll probably be the chair of that committee.’ I showed up and went to meetings and I think by the third year I was a chair of that committee” (115)

“So basically, what I told him is that ‘You need to go to the bylaws… and then use that as a tool to accomplish what you want.’ …when he did go to the bylaws, he found that there was a pretty clear pathway as to what you need to do to get promoted… and I just had to coach him through some of the steps.” (105)

|

|

Giving Resources

|

|

“There was a younger faculty and the coaching has been, ‘you want to advance your career with scholarship? I will work with you on this paper, and let me be your guide to how to frame the question, how to write it, how to be engaged that way, and then get you some faculty development in a particular area.’” (112)

“I was running a steering committee, and we used to all go around and give our updates. After a few of meetings, she pulled me aside, and said “you are wasting my time… the fact that we are giving updates is fine, but you need to leverage our time and our expertise, so what you need to do is come to us with questions. You need to take advantage of us.’ [S]he actually gave me a resource that I could look at in terms of how to run meetings effectively.” (111)

|

|

Performing Critical Appraisal

|

|

“Look at where there may be some skill gaps in the role they are currently playing and if that is going to be an important skill for the next level of their career, I will point that out to them and suggest ways that they might acquire those skills.” (103)

“But it was the first time she had written anything and so she got to go through the process and see what that looks like and I realized that she is actually very much better at this than she realized. She just needed somebody to kind of say, ‘Hey, you are actually good at this. You do not need to be afraid of it.’” (112)

|

|

Giving Feedback

|

|

“I would just touch base with her periodically... getting very practical feedback about how to manage one thing versus another thing or just feedback whether I could have done something that had already transpired better than I had actually done.” (106)

“So here is the feedback that I have for you about watching your interaction with the chair. This is why I think he is hearing you wrong even though I know what you were going with... I feel like she heard that feedback, but then she took it on her own and did what she needed to do.” (114)

|

|

Discussing

|

|

“I told them, "What have you thought about that? What would be the worst thing to happen if you did that?" I am… making suggestions, "Okay, you need to do that to get promoted." I have them think through things and let them make the decision. (119)

“You know, I try to, first of all, just start by asking them how things are going from their point of view … What is your perception of what is going on here? So I really approach it from … I want to know your perspective of what is going on. And so, I try to put myself in the position of learning what their needs are and what their perception is. And then I take the approach of… I am wondering how you think I can be helpful to you.” (117)

|

|

Scaffolding

|

|

“It was this senior faculty who was very well positioned who kind of took me under his wing and promoted me as someone who could do this work… he helped me write the reports and to make sure they ended up in the in the right people's hands so that actually money could flow and policies could change, that something happened from a result of that.” (109)

“Once we had set out what the parameters of the position of their job, or their responsibility is, he would basically let you do your job unless you were not doing it correctly. He was always there to help you through different situations... I would try the things that he suggested. When it did not work and he would modify it.” (110)

|

Sponsorship

Participants identified six main actions sponsors perform, as listed here. Table 3 presents quotes that illustrate each of these main actions performed by a sponsor:

1. Identifying opportunities: The sponsor identifies positions and experiences for the sponsoree’s professional growth.

2. Recognizing an individual’s strengths: The sponsor helps the sponsoree articulate and connect their unique talents with the opportunities in front of them.

3. Encouraging opportunity-seeking: The sponsor recommends an opportunity and prompts the sponsoree to embrace it.

4. Offering tangible support: The sponsor allocates the sponsoree funding, time, and resources to facilitate success or enhance candidacy for future opportunities.

5. Optimizing candidacy: The sponsor introduces the sponsoree to training and experiences that improve their résumé. They also enhance the sponsoree’s local and national visibility by helping them network.

6. Nominating as a candidate: The sponsor puts forward the sponsoree’s name for an award or position and makes a case for their fitness. At times, they suggest the person’s name to those in charge as their own replacement.

7. Promising support: Sponsors offer to make themselves available to help further develop the skills of sponsorees if they get a position. They offer guidance and resources along the way to ensure the sponsoree’s success.

Coaching

Participants identified seven main actions a coach performs, as listed in this section. Table 4 presents quotes that illustrate each of these main actions performed by a coach:

1. Clarifying: The coach explicitly describes to the coachee the how, what, why, where, and when of specific skills or situations. Such explanations aim to help the coachee navigate professional situations and attain a specific end. The coach also explains the underlying rationale of the suggested approach.

2. Advising: The coach offers tailored guidance to the coachee and instructs them on best practices based on experiences. They act as guides and suggest strategies to achieve the desired outcome.

3. Giving resources: The coach provides the coachee with the means to link with different opportunities or connect to alternative options.

4. Performing critical appraisals: The coach helps the coachee asses the quality of their work and identify skill needs. To achieve this task, the coach observes the coachee or sees examples of their actions (eg, reads their emails, listens to talks they give) to help them recognize what needs improvement.

5. Giving feedback: The coach provides the coachee with assessments of their performance. They tell them what they are good at and provide encouragement. They point out areas where the coachee needs work and help the coachee work with their strengths and weaknesses.

6. Reflecting: The coach has a conversation with the coachee to ask what they are thinking about, check in, and help them contemplate. In specific cases, they talk about how the coachee felt and consider different scenarios for responding to a situation. The coach shares perspectives and reaffirms values in a nonjudgmental approach.

7. Scaffolding: The coach gets involved with the coachee on a project and engages in the iterative development process. They help them complete the tasks that are new or outside their comfort zone. For example, in coauthoring a paper, the coach lets the coachee write the first draft, then the coach makes edits and give examples of improvement areas rather than carrying out the work themselves.

Mentoring

Participants identified six main actions the mentor performs, as listed in this section. Table 5 presents quotes that illustrate each of these main actions performed by a mentor:

1. Checking in: The mentor keeps an open door and stays available for their mentee. More importantly, they actively reach out by calling, emailing, or setting up regular meetings. Over time, a long-term relationship solidifies between them, and in many instances, it becomes a friendship.

2. Listening: The mentor provides an opportunity for the mentee to talk and ask questions. They recognize what the mentee wants and learn about the mentee’s interests. They help mentees interpret situations and gain perspective as the mentor acts as a sounding board.

3. Sharing wisdom: The mentor describes and reveals the written and unwritten rules of how things work in academia. This presents opportunities and transfers information regarding potential new directions for the mentee.

4. Directing: The mentor describes a pathway for achieving career success by helping the mentee understand the organization’s culture, naming learning strategies and calling attention to blind spots.

5. Supporting: The mentor provides guidance, encouragement, and protection to the mentee as they mature in their personal lives and grow their careers.

6. Collaborating: The mentor works with the mentee to develop projects and helps them build their skills to complement others on the team.

|

Checking In

|

|

“They tell me what they are doing. If they are working on any research projects, administrative things that they are doing, some teaching that they might be doing, they start asking me questions and we bounce back and forth. They ask for feedback about how they are doing, and I have not had to help them change direction because I think they are going in the right direction. That is kind of the way, and for having done this for 25 years.” (102) “The one mentor that I will point out was initially a faculty member in the residency where I was. But the reality is that we were both the same age. We were in the same stage of life in terms of family, in terms of life cycle development. We were both MD, PhDs... We clicked and became best friends. But in the process, we also help each other. When he is making a decision or I am making a decision, we talk. We balance with it out. But we begin that conversation by saying, "Hey, how are your kids? what is going on? What is going on with so and so." I think it is the quality of the relationship that is an important piece.” (101)

|

|

Listening

|

|

“So she did not necessarily ever have to write a letter of recommendation or do anything in particular, it was just more she was far enough ahead of me that I could ask her questions about what to do.” (114) “I mean there was a particular female faculty who arrived at my previous medical school at about the same time. So we talked a lot about what she wanted her career to be and how she wanted her life to turn out. That was probably over the space of the whole 22 years that we were at the same institution.” (110)

|

|

Sharing Wisdom

|

|

“And I know with family physicians who are often not great with systems workers, but we don't always know a lot of the in's and out's of how, of what's important and how things work. So, I think it's been critically important for others to share with me what's valued and how the how the world works and to share those out.” (118) “He was just intentional about providing opportunities for growth or opportunities for leadership.” (120)

|

|

Directing

|

|

“And even if I was pretty sure I knew what I wanted to do in a given situation, I will go get perspective from one of those folks just to hear their take on it. Occasionally, I'd be surprised and get a completely 180 opinion from what I thought I wanted to do and that is always eye-opening. But even when they were in agreement with me, sometimes… if I wanted to take a right turn and they agreed with the right turn but for completely different reasons that was educational for me.” (115) “I was focusing on three projects… he very gently said, ‘I know these are all important to you. Every time you go away over there to work on that third project, you are kind of pulling your energy, and your attention, your focus away from the other two when it is not additive.’ He did not say, you need to give up, he said, you need you think about it, and you need to think about where you want to [go], where your work could be more additive. It was hard… I felt like it was a one of those moments where I felt supported. I felt guided in a place that I did not realize I had my own blind spot.” (111)

|

|

Supporting

|

|

“Well, I will say that probably one of my first professional mentors was my residency program director at the time when I was a resident and not only did he guide my progression through the residency, but he became really a source of wisdom and guidance for my first job after residency.” (109) “When Dr. [name] came, he was just the same way, warm, supportive, and open-door. I do not know that we had any kind of scheduled time. But anytime I had a problem or concern or whatever, he was always available to me.” (113)

|

|

Collaborating

|

|

“I have, for example, a new faculty member… We meet monthly. We write papers together. We will do those sorts of things.” (101) “I think it is kind of a combination of... On my end, I just making myself available and saying, "How can I help you?" Or how can we work together?” (112)

|

Our study clarified the distinctions of SCM for faculty development. We examined how to employ SCM from the perspective of chairs of family medicine departments, who influence organizational processes and provide resources that drive faculty development. Department chairs can significantly influence the future academic workforce. This highlights the importance of their own personal and professional experiences as well as how they subsequently lead their departments. We provided a detailed description of the processes and functions that take place with each approach.

Our work moves beyond previous studies that looked at the subject matter separately or relied on expert opinions in developing how-to recommendations. Extensive studies have looked at SCM, with more emphasis on the last two. 18-23 Recently, however, sponsoring has emerged as a topic of interest to help address the lack of diversity in leadership positions, which are typically dominated by White males. 10, 13, 24 The three roles are distinct but can be seen as ambiguous and interchangeable because they are often examined and described separately. The added clarity based on our empirical work will be helpful guiding chairs and other leaders and enhancing their skills in developing a diverse professional workforce. 1, 2 Further, our findings invite conversation to intentionally incorporate SCM into the chairs’ responsibilities. We present SCM as an identifiable series of actions that do not happen by chance. SCM require fidelity to a complex process associated with specific roles, responsibilities, and a sequence of steps within a defined time frame to achieve the greatest faculty productivity and advancement. To succeed at SCM, department chairs need to build scheduled time and spaces with faculty to complete the elements our paper outlines for each strategy. Ensuring success also requires monitoring to evaluate the impact of these actions and inform the need for course correction. Without this intentionality, activities related to SCM are likely to rely on similarities in interest, values, gender, race, or other cultural characteristics. Making SCM intentional with defined expectations could help address the inattentiveness (at best) and often discrimination and exclusion that currently limits the diversity in academic medicine leadership. 25

An institutional SCM program must balance multiple priorities and economic constraints. Decision-making for faculty and departmental leaders reflects institutional requirements for clinical, teaching, and research productivity. Unscheduled half-days that are available for SCM are challenging to identify. Our study calls attention to building SCM functions into the written position descriptions of high-level leaders like department chairs, and for SCM to be defined as part of the job and not add-on elements attended to only if time allows. Such functions can be included in offer letters and job descriptions as explicit tasks the chair will be held accountable for performing. Further, institutions should consider incorporating an evaluation of SCM in annual performance appraisals, linking SCM accomplishments to faculty incentive plans, and intentionally allocating budgets to fund SCM training activities. Such funds can be spent to hire coaches for the chair and to train faculty champions to develop infrastructures for SCM.

Our study has three main practical implications. First, we distinguished the definitions and actions of the three approaches so that leaders can purposefully select the approaches most likely to achieve individual faculty goals. Over time, using all of these tools in a balanced mixture is likely optimal. These distinctions set expectations for the persons receiving and providing SCM so they can stay focused on actions appropriate to the mode of SCM and the setting. Second, explicit expectations for action taking place across SCM modes allows for evaluation of the effectiveness of these interactions. This evaluation of the effectiveness of individuals in leadership positions can use the perspective of the person performing the act or of the recipient. Third, naming these actions as distinct and intentional facilitates skill development for the person performing the role or function. A recipient can also learn to explicitly seek or become more likely to receive all three. Learning to provide and receive SCM could prove effective in increasing the use and equitable delivery of these approaches.

Our study has two major strengths. We ensured a diverse sample of participants by accounting for ethnicity, race, generational span, and sexual orientation. This diversity of perspectives was fruitful in showing various patterns of interactions and approaches that represent the broad and deep cultural pipeline in our current workforce that represents the nation. We studied the experiences of chairs in family medicine, but the broad spectrum of family medicine, including pediatric care, obstetrics, and some procedural training, allows for broader generalizability of our findings to other disciplines. This approach makes our findings relevant to most, if not all, of academic medicine.

Our study has three main limitations. First, the topics of SCM have become more salient in the past few decades. The experiences of chairs may have varied by their seniority in the field, and some might have received or provided SCM without using the current terminology. Second, our work depended on the recall of our research participants over time, sometimes multiple decades. Remembering experiences and describing them as they occurred may vary from one participant to another. Third, we fell short of addressing diversity in the broadest sense. We included a diverse sample, but we have not yet examined differences in any diversity domains. Further, although we included representations of race/ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation, we were not intentional in exploring religious, language, ability, or other types of diversity.

Future research will explore the experiences of minorities and women in SCM, including supporting factors and strategies they use to build resiliency. We will look closely at the diversity of experiences by race and gender, addressing intersectionality and additional characteristics of diversity. We will also explore how individuals from underrepresented groups compensate for the lack of SCM in their workplace. Further, we will explore efficient learning strategies by gauging the perspectives of participants around learning objectives, and the content will provide an innovative approach to developing future departmental leaders. Finally, we will develop evaluation tools to use within the context a 360° evaluation of those in the position of leadership to examine whether they are providing adequate SCM that equitably meets the needs of all for whom they are responsible. We also could explore the chairs’ ability to utilize this information to better identify faculty who have these skills more naturally, and proceed to delegate some of the responsibility to those faculty who could help. These additional steps will not only support the importance of SCM as part of the department chairs’ approach to faculty development, but emphasize its role in ensuring a vibrant academic workforce that represents our nation.

References

-

Baker EL, Hengelbrok H, Murphy SA, Gilkey R. Building a coaching culture-the roles of coaches, mentors, and sponsors. J Public Health Manag Pract

. 2021;27(3):325-328. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000001368

-

Hengelbrok H, Baker EL. Connecting with coaches, mentors, and sponsors: advice for the emerging leader. J Public Health Manag Pract

. 2021;27(4):421-423. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000001380

-

Shuler H, Cazares V, Marshall A, et al. Intentional mentoring: maximizing the impact of underrepresented future scientists in the 21st century. Pathog Dis

. 2021;79(6):38. doi:10.1093/femspd/ftab038

-

Johnson MO, Fuchs JD, Sterling L, et al. A mentor training workshop focused on fostering diversity engenders lasting impact on mentoring techniques: results of a long-term evaluation. J Clin Transl Sci

. 2021;5(1):e116. doi:10.1017/cts.2021.24

-

Louissaint J, May FP, Williams S, Tapper EB. Effective mentorship as a means to recruit, retain, and promote underrepresented minorities in academic gastroenterology and hepatology. Am J Gastroenterol

. 2021;116(6):1110-1113. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001125

-

Fielden SL, Davidson MJ, Sutherland VJ. Innovations in coaching and mentoring: implications for nurse leadership development. Health Serv Manage Res

. 2009;22(2):92-99. doi:10.1258/hsmr.2008.008021

-

-

Seehusen DA, Rogers TS, Al Achkar M, Chang T. Coaching, mentoring, and sponsoring as career development tools. Fam Med

. 2021;53(3):175-180. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.341047

-

-

Gottlieb AS, Travis EL. Rationale and models for career advancement sponsorship in academic medicine: the time is here; the time is now. Acad Med

. 2018;93(11):1620-1623. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002342

-

Lovell B. What do we know about coaching in medical education? A literature review. Med Educ

. 2018;52(4):376-390. doi:10.1111/medu.13482

-

Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med

. 2010;25(1):72-78. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1165-8

-

Ayyala MS, Skarupski K, Bodurtha JN, et al. Mentorship is not enough: exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine. Acad Med

. 2019;94(1):94-100. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002398

-

Ness RB, Samet JM. How to be a department chair of epidemiology: a survival guide. Am J Epidemiol

. 2010;172(7):747-751. doi:10.1093/aje/kwq268

-

Buckley PF. Reflections on leadership as chair of a department of psychiatry. Acad Psychiatry

. 2006;30(4):309-314. doi:10.1176/appi.ap.30.4.309

-

Koopman RJ, Thiedke CC. Views of family medicine department Chairs about mentoring junior faculty. Med Teach

. 2005;27(8):734-737. doi:10.1080/01421590500271209

-

Coe C, Piggott C, Davis A, et al. Leadership pathways in academic family medicine: focus on underrepresented minorities and women. Fam Med

. 2020;52(2):104-111. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.545847

-

Curtin N, Malley J, Stewart AJ. Mentoring the next generation of faculty: supporting academic career aspirations among doctoral students. Res High Educ

. 2016;57(6):714-738. doi:10.1007/s11162-015-9403-x

-

Berk RA, Berg J, Mortimer R, Walton-Moss B, Yeo TP. Measuring the effectiveness of faculty mentoring relationships. Acad Med

. 2005;80(1):66-71. doi:10.1097/00001888-200501000-00017

-

LLewellen-Williams C, Johnson VA, Deloney LA, Thomas BR, Goyol A, Henry-Tillman R. The POD: a new model for mentoring underrepresented minority faculty. Acad Med. 2006;81(3):275-279. doi:10.1097/00001888-200603000-00020

-

Norman MK, Mayowski CA, Wendell SK, Forlenza MJ, Proulx CN, Rubio DM. Delivering what we PROMISED: outcomes of a coaching and leadership fellowship for mentors of underrepresented mentees. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4793. doi:10.3390/ijerph18094793

-

Ericsson KA. Acquisition and maintenance of medical expertise: a perspective from the expert-performance approach with deliberate practice. Acad Med

. 2015;90(11):1471-1486. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000939

-

Wenrich MD, Jackson MB, Maestas RR, Wolfhagen IH, Scherpbier AJ. From cheerleader to coach: the developmental progression of bedside teachers in giving feedback to early learners. Acad Med

. 2015;90(11)(suppl):S91-S97. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000901

-

Levine RB, Ayyala MS, Skarupski KA, et al. It’s a little different for men”-sponsorship and gender in academic medicine: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med

. 2021;36(1):1-8. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05956-2

-

Holmes O IV. Redefining the way we look at diversity: a review of recent diversity and inclusion findings in organizational research. Equal Divers Incl

. 2010;29(1):131-135. doi:10.1108/02610151011019255

There are no comments for this article.