Background and Objectives: Burnout is prevalent among clinicians and faculty. We sought to understand the impact of a recognition program designed to reduce burnout and affect engagement and job satisfaction in a large academic family medicine department.

Methods: A recognition program was created in which three clinicians and faculty from the department were randomly selected each month to be recognized (“awardees”). Each awardee was asked to honor a person who had supported them (a “hidden hero” [HH]). Clinicians and faculty not recognized or selected as an HH were considered “bystanders.” Interviews were completed with 12 awardees, 12 HHs, and 12 bystanders for a total of 36 interviews. We used content analysis to qualitatively evaluate the program.

Results: Assessment of the “We Are” Recognition Program resulted in the categories of impact (subcategories: process positives, process negatives, and fairness of program) and HHs (subcategories: teamwork and awareness of the program). We conducted interviews on a rolling basis and made iterative changes to the program based on feedback.

Conclusions: This recognition program helped create a sense of value for clinicians and faculty in a large, geographically dispersed department. It represents a model that would be easy to replicate, requires no special training or significant financial investment, and can be implemented in a virtual format.

Increased recognition and feeling valued are associated with engagement, job satisfaction, and reduced turnover among clinicians and faculty (ie, advanced practice providers [APPs] who are faculty, APPs who are clinicians, faculty who are clinicians, and faculty who are not clinicians) in medicine. 1-5 Insufficient recognition increases risk of burnout and is associated with faculty leaving academic medicine. 6, 7

In seeking to address local levels of burnout that are consistent with national averages, 8 and based on internal data suggesting a need for fairness in a recognition system, 9 we created a recognition program with particular care regarding fairness and inclusion to build group cohesion and a sense of shared values. 3 We implemented the program on the two campuses of our large academic family medicine (FM) department.

We explored clinician, faculty, and staff experiences of the program.

“We Are” Recognition Program

Starting in October 2019, from a department of 145 clinicians and faculty, three individuals were selected monthly to be recognized using a random number generator in Excel and were then removed from future eligibility (Table 1). Awardees were selected randomly to mitigate concerns regarding favoritism and fairness 10 and to promote the concept that all are doing valuable work and are worthy of recognition. Clinicians and faculty were asked to name someone who had helped them with their accomplishments, who would be recognized with them as their hidden hero (HH). All clinicians and faculty were expected to be present at department meetings, where each awardee received a $100 Amazon gift card and was recognized by having positive comments from peers read aloud. The awardees then shared why they selected their HHs. In April 2020, department meetings and awardee recognition changed to a virtual format due to COVID-19. The program is still ongoing.

This study was approved by the institution’s IRB (STUDY#11378).

|

Timepoint

|

Action

|

Explanation

|

|

One month prior to department meeting

|

Randomly selecting clinicians and faculty

Selecting a hidden hero

Coworker perspective

|

Program leadership sends recognition notification to selected clinicians and faculty via email. Recognized individuals are able to opt in or out.

Those who opted in are asked to select a hidden hero and to provide a statement regarding why they were chosen. a,b

Coworkers of the clinicians and faculty being recognized are asked to provide positive comments about them. Coworkers were identified through peers and leaders at clinical site, and areas of academic expertise known to the investigators (eg, for medical student clerkship director requested input from Vice Chair for Education).

|

|

Department meeting

|

Recognize awardees

Publicly recognize hidden hero(es)

|

Approximately 10 minutes of each monthly department meeting is devoted to publicly recognizing the three selected clinicians and faculty by summarizing the positive statements gathered from their coworkers and giving them an award certificate and a $100 Amazon gift card.c

The recognized clinicians and faculty are each invited to share why they chose to recognize their respective hidden hero(es).

|

|

One day after department meeting

|

Send official recognition to hidden hero(es)

|

Hidden hero(es) are mailed a letter of gratitude for their contributions,b and a certificate signed by department leadership.d

|

Participants

Clinicians and faculty receiving recognition were labeled as awardees (n=20), individuals who were selected by awardees as HHs (n=36), and clinicians and faculty who were not awardees or HHs as bystanders (n=89). Awardees were able to opt out of receiving recognition. All awardees, HHs, and bystanders were eligible to be interviewed.

Interviews

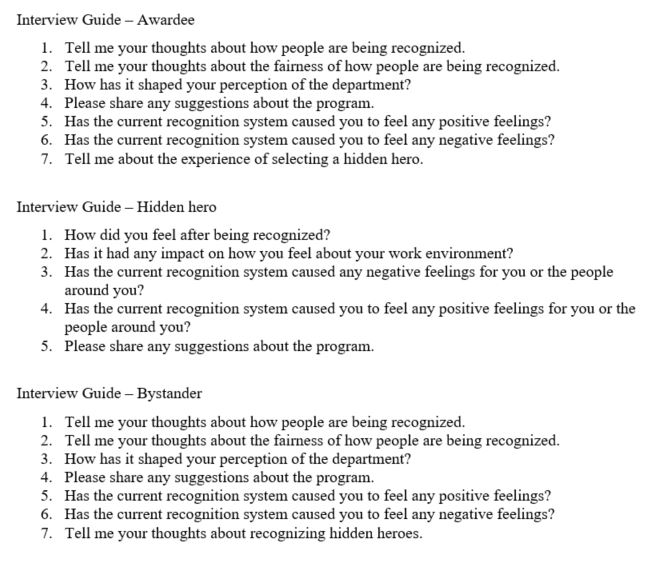

All individuals who were recognized, their selected HH, and randomly selected bystanders were invited via email 1-2 weeks following recognition to participate in an interview (Figure 1) during which they were asked about the program. Interviews took an estimated 10 minutes and were analyzed on a rolling basis, facilitating continuous program adjustments in response to feedback. Adaptations are footnoted in Table 1. Interviews were conducted from November 2019 through April 2020.

Qualitative Analysis

We used deductive content analysis for the program evaluation. Authors J.P. and J.A.R. developed a categorization matrix to identify main, generic, and sub categories based on a previous study 9 and interview questions. 10 We reviewed the interviews for content and then grouped the coded content based on the conceptual categories. Using a consensus approach, we reached 100% agreement for each category.

Twelve awardees, 12 bystanders, and 12 HHs were interviewed to ensure saturation of qualitative data (Table 2). 11 Interviews lasted 8.09 minutes on average. Table 3 contains the main, generic, and sub categories along with representative quotes.

|

|

Awardees, n=12

|

Hidden Heroes, n=12

|

Bystanders, n=12

|

|

Sex, n (%)

|

|

|

|

|

Male

|

6 (50)

|

3 (25)

|

4 (33.3)

|

|

Female

|

6 (50)

|

9 (75)

|

8 (66.7)

|

|

Position, n (%)

|

|

|

|

|

Faculty

|

8 (66.7)

|

1 (8.3)

|

11 (91.7)

|

|

Nonfaculty clinicians

|

4 (33.3)

|

7 (58.4)

|

1 (8.3)

|

|

Staff

|

0 (0)

|

4 (33.3)

|

0 (0)

|

|

“We Are” Recognition Program

|

|

Impact of Program

|

|

Process Positives

|

“I feel like it does increase my appreciation of others’ achievements and those things that other people are doing with their day.”

“It’s nice to hear what other people truly feel about their colleagues.”

“I think it’s nice to see other providers recognized and kind of learn about what their practice is like and draw inspiration from them and what they’re doing. And I think that it is nice to be recognized. I feel like a lot of providers in family medicine are pretty humble so they’re not like out there announcing their accomplishments and things. This is a nice chance for them to get a little bit of the spotlight and a chance for their colleagues to see the great things they’re doing.”

|

|

Process Negative

|

“… the weird part is everybody’s going to get recognized at some point in time so there’s nothing like … you won any kind of a contest for this.”

“My perspective, I am not one that likes to sort of be the center of attention or the focus of attention. And so it was kind of embarrassing for me.”

“I mean I personally did not necessarily feel that I needed more recognition than what I was getting. And part of it might be that I think I’m reasonably outspoken and proactive so I have gotten some.”

|

|

Fairness of Program

|

“I think the best part that I like about it is that everybody has a chance to be recognized and sort of be placed in the forefront and kind of be recognized for whatever they do.”

“I think it’s nice we’re recognizing people who might not have gotten recognition in the past.”

“I think the process is fair because everybody has an equal chance and probability of getting picked.”

|

|

Selecting a

Hidden Hero

|

|

Teamwork

|

“I think the hidden heroes is absolutely wonderful. None of us can do really anything substantial without at least one person behind us.”

“I thought it was really nice to kind of reflect and think about who really contributes to your day and who contributes or impacts you(r) day in a positive manner.”

“I think a lot of times physicians are in the headlines and physicians and nurses in general associate with delivering healthcare. But the reality is there’s a multidisciplinary chain and sometimes people outside of the clinic and outside of that direct domain that are really contributing to the success.”

|

|

Awareness of Program

|

“I know it happened because two other people congratulated me but I didn’t know anything about it.”

“I came into work and a letter and certificate were laying on my desk so that’s how I found out.”

“I was aware of the program’s existence. I had no idea there was the hidden hero component to it.”

|

Main Category: “We Are” Recognition Program

Questions and subsequent interviewee responses related to the processes and evaluation of the “We Are” Recognition Program were the focus of our categorization matrix. We reviewed the data for content and coded for correspondence with the categories impact and HHs. The content of each of these categories is described through subcategories as follows.

Generic Category: Impact of Program

Three subcategories were identified related to impact of the program on the department: process positives, process negatives, and fairness of program.

Process Positives. Participants found the program to be positive, as it led to wider awareness of the work of clinicians and faculty. Many expressed appreciation of the program initiative to promote well-being.

Process Negatives. Awardees appreciated being recognized but felt that the random selection process diminished the overall impact of the recognition. Some expressed a lack of enthusiasm for public recognition and having to speak at the faculty meeting.

Fairness of Program. Many interviewees found the program and selection process to be fair and considerate of all clinicians and faculty.

Generic Category: Selecting a Hidden Hero (HH)

Two subcategories related to selecting an HH were identified: teamwork and awareness of the program.

Teamwork. Awardees appreciated the opportunity to recognize HHs and expressed gratitude for their recognition.

Awareness of Program. Participants reported being aware of the program if they attended department meetings. Those who did not attend department meetings (often HHs) were not aware unless someone told them about it. Bystanders agreed with the need for better recognition for HHs.

The majority of interviewees perceived the program as fair and as effective in facilitating comradery and positive messaging regarding intradepartmental work. Clinicians and faculty derived positive meaning from feeling empowered to recognize their coworkers. All groups noted appreciation for the accolades, highlighting the benefits of the manner in which the award was delivered. Most participants did not identify the gift card as essential. The results reinforce the role of acknowledgment (eg, positive comments from colleagues) in feeling valued. 7 Other health systems could implement a similar program that does not use financial rewards.

Our single department and small, relatively homogeneous study population limits generalizability and our ability to identify themes related to differences in recognition preferences based on diversity factors. Since a majority of awardees and bystanders were faculty and a majority of HHs were clinicians, we were not able to draw inferences regarding group differences.

This recognition program, developed through an iterative process, represents a model that could be easily replicated, requires no special training or significant financial investment, and can be implemented virtually. Deeper exploration of the elements of the program that contribute to clinicians and faculty feeling valued by the organization may help optimize effectiveness. Its impact can be further assessed through broader implementation and study.

Financial Support

This research was supported by the Penn State College of Medicine Office of Faculty and Professional Development Wellness Mini-Grant Program and the Thomas L. and Jean L. Leaman Research Endowment, Department of Family & Community Medicine.

Presentations

This research was presented as a poster presentation for the 2019 NAPCRG Annual Meeting and the 2019 FMEC Annual Meeting.

References

-

Klein CJ, Dalstrom MD, Weinzimmer LG, Cooling M, Pierce L, Lizer S. Strategies of advanced practice providers to reduce stress at work. Workplace Health Saf

. 2020;68(9):432-442. doi:10.1177/2165079920924060

-

Simpkin AL, Chang Y, Yu L, Campbell EG, Armstrong K, Walensky RP. Assessment of job satisfaction and feeling valued in academic medicine. JAMA Intern Med

. 2019;179(7):992-994. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0377

-

Renger D, Miché M, Casini A. Professional recognition at work: the protective role of esteem, respect, and care for burnout among employees. J Occup Environ Med

. 2020;62(3):202-209. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001782

-

Condit M, Hafeman P. Advanced practice providers: how do we improve their organizational engagement? Nurse Lead

. 2019;17(6):557-560. doi:10.1016/j.mnl.2019.02.004

-

Pololi LH, Krupat E, Civian JT, Ash AS, Brennan RT. Why are a quarter of faculty considering leaving academic medicine? A study of their perceptions of institutional culture and intentions to leave at 26 representative U.S. medical schools.

Acad Med. 2012;87(7):859-869.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182582b18

-

Bucklin BA, Valley M, Welch C, Tran ZV, Lowenstein SR. Predictors of early faculty attrition at one Academic Medical Center. BMC Med Educ

. 2014;14(1):27. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-14-27

-

Lin KS, Zaw T, Oo WM, Soe PP. Burnout among house officers in Myanmar: A cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg (Lond)

. 2018;33:7-12. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2018.07.008

-

Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc

. 2019;94(9):1681-1694. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.10.023

-

-

Riley TD, Radico JA, Parascando J, Berg A, Oser TK. Challenges in effective faculty and provider recognition to enhance engagement. Fam Med

. 2022;54(6):461-465. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2022.324428

-

Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. SAGE Publications; 2017.

There are no comments for this article.