Background and Objectives: Family medicine is the most demographically diverse specialty in medicine today. Specialty associations and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) urge residency programs to engage in systematic efforts to recruit diverse resident complements. Using responses from program directors to the ACGME’s mandatory annual update, we enumerate the efforts in resident recruiting. This allows us to compare these statements to the recommendations of two highly respected commissions: the Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce and the Institute of Medicine’s In the Nation’s Compelling Interest: Ensuring Diversity of the Healthcare Workforce.

Methods: We compiled the annual updates from 689 family medicine programs and analyzed them using a qualitative method called template analysis. We then classified the efforts and compared them to the recommendations of the Sullivan Commission and Institute of Medicine (IOM).

Results: Nearly all (98%) of the programs completed the portion of the annual update inquiring about recruiting residents. The Sullivan Commission and IOM recommended 23 steps to diversify workforce recruiting. We found that programs engaged in all but one of these recommendations. Among the most frequently employed recommendations were doing holistic reviews and using data for planning. None mentioned engaging in public awareness campaigns. Programs also implemented eight strategies not suggested in either report, with staff training in nondiscrimination policies being among the most frequently mentioned. Among program efforts not included in the Sullivan Commission or IOM recommendations were extracurricular activities; appointing diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) committees or advocates; subinternship (Sub-I) experiences; recruiting at conferences; blind reviews; legal compliance; and merit criteria. In total, we found 31 interventions in use.

Conclusions: The Sullivan Commission’s guidance, IOM recommendations, and program-developed initiatives can be combined to create a comprehensive roster of diversity recruiting initiatives. Programs may use this authoritative resource for identifying their next steps in advancing their recruiting efforts.

Family medicine (FM) is the most diverse specialty in contemporary graduate medical education (GME); however, at a national scale, the demographics of FM residency have not achieved parity with the general US population. 1 This study explored what efforts FM program directors reported making to diversify their resident complements in order to definitively roster the range of options that programs may consider when they contemplate their next steps toward greater inclusivity. To do this, we began with the annual update reports that programs are required to file with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). For those reports, program directors were prompted to describe their efforts to recruit and retain diverse resident complements. We then correlated the program directors’ statements with recommendations on diversifying America’s health workforce from two blue-ribbon committees. We hypothesized that the recommendations of the blue-ribbon committees would be reflected in the program directors’ statements to the ACGME.

Two blue-ribbon commissions each produced a groundbreaking report. The Sullivan Commission’s Missing Persons: Minorities in the Health Professions 2 and the Institute of Medicine’s In the Nation’s Compelling Interest: Ensuring Diversity in the Health Care Workforce 3 were published in 2004 with significant input from leading figures in medicine, advocacy, government, and business. Since their publication, many of the country’s leading medical organizations have echoed the recommendations. For example, the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) has focused on related themes, such as bringing more women and racial or ethnic minorities into medicine. 4 The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) urged policymakers to prioritize research and initiatives for increasing diversity in the physician workforce, noting that doing so would contribute to providing care in underserved areas and remediate population health disparities. 5, 6 More recently, the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine adopted a consensus statement on diversity, equity, and inclusion, which addressed workforce development. 7

The effectiveness of these recommendations has been supported in scholarly literature. For example, Stoesser and her colleagues instituted an array of recruiting activities, which together resulted in increasing numbers of Hispanic and Asian residents at their institution. 8 These initiatives included ensuring diversity on interview panels, recognizing applicants for overcoming hardships, engaging their organization’s diversity office, and priority interviewing for candidates of disadvantaged backgrounds. Similarly, Wusu et al reported increasing minority matches to their program through strategic outreach, carefully worded interview questions, and monitoring of outcome data. 9

Similarly, Emery et al 10 found effectiveness in removing organizational barriers, building pipelines with K-12 or baccalaureate levels of education to foster student attachment to the study of science, and helping minority students overcome stereotypes or self-perceptions that hinder academic achievement.

The Sullivan Commission and Institute of Medicine (IOM) reports, however, were unique in their authoritative contributors and in the breadth of their recommendations. To date, no effort has been made to synthesize their recommendations and contrast them with what residency programs are doing en masse. This synthesis could provide a single menu to serve as a resource for programs that may need guidance on diversifying their resident complements. Some attempts have been made through survey research to quantify diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives currently in use. 11 We, instead, relied on statements that program directors made to the ACGME. The ACGME’s common program requirements (CPRs) 12 mandate that accredited programs “engage in practices that focus on mission-driven, ongoing, systematic recruitment and retention of a diverse and inclusive workforce of residents and fellows” (p. 5). The annual updates prompt program directors to explain how they fulfill that CPR. 12 The annual updates provide the widest coverage of the steps programs take to fulfill this ACGME CPR of diversifying resident complements.

In this paper, we report on the FM program directors’ annual update responses addressing how they recruited residents. With 701 programs, FM makes up the greatest proportion (13%) of residency programs across all specialties. In 2020, FM had the second largest proportion of total residents (11.5%, with 13,725 residents), and FM has achieved parity in terms of gender (53.5% of residents were female). As such, FM should offer the widest possible variety of initiatives in this regard and therefore serve as a template for other disciplines.

This paper is both a qualitative comparison of the FM program directors’ responses from annual updates and the recommendations of the Sullivan Commission and IOM. In the nearly 20 years since the two commissions’ recommendations were published, we thought that programs may have undertaken initiatives of their own creation, which our methods allowed us to document. Since 2019, the ACGME’s annual updates have prompted program directors to "describe how the program will achieve/ensure diversity in trainee recruitment, selection, and retention." This item corresponds with the ACGME’s CPR that programs engage systematic efforts to recruit and retain a diverse resident workforce. Since 2019, the annual updates have been reported by program directors, or their staff, and the results are stored in the ACGME’s accreditation data system.

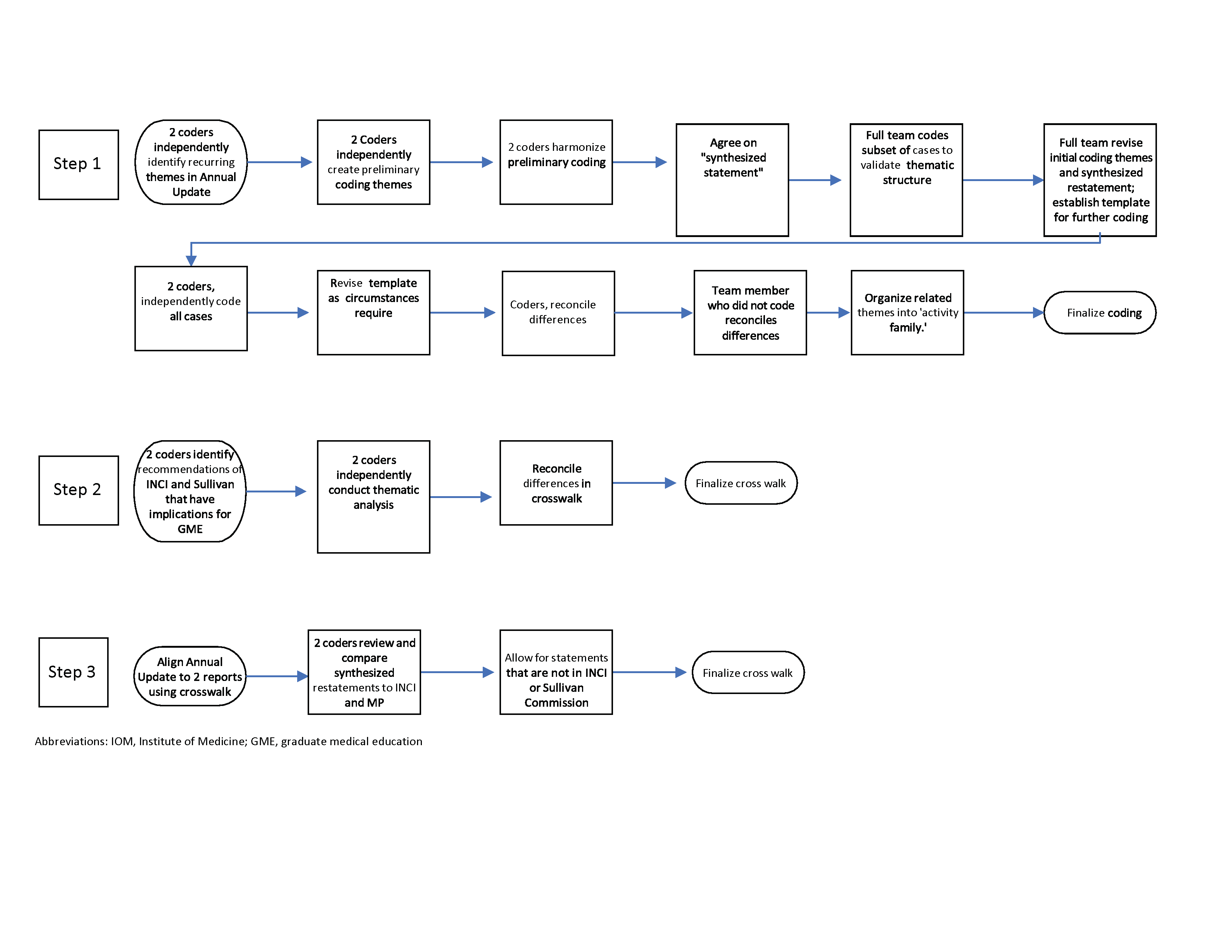

Our analytical methods were rooted in template analysis. 13, 14 Template analysis organizes open-ended statements by coding them into important and recurring themes. 15 First, our project team received an electronic file containing program directors’ responses from the annual update. Data fields specifically designed to record the program’s name, the name of the sponsoring institution, location, and the name of the program director were excluded from the file delivered to the project team. However, some authors of annual update responses included identifying information in their narratives. Those responses were left intact when delivered to the research team.

Second, we imported the annual update into NVivo, a software application commonly used in qualitative research. There we used a system of open coding to create an initial classification of recurring themes at a granular level. 16 For example, one program director reported, “Quarterly Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion sessions required for all residents and faculty were integrated into the didactic schedule,” while another said, “Formal training will continue to educate all learners and faculty about unconscious bias, racial disparities, and cultural competence and their effects on healthcare outcomes.” We coded comments like these under the theme DEI curriculum.

Two members of the project team independently reviewed and coded each of the annual update responses to document recurring themes. Then we combined those two lists into one preliminary template documenting the recurring themes that both team members found.

Next, all three members of the project team worked in tandem to code a randomly selected set of 20 program directors’ responses using this preliminary template. This exercise allowed us to (a) eliminate redundant or extraneous codes, (b) add new codes, (c) ensure that the project team was like-minded about the coding, and (d) ensure that we were of like mind about any restated activity theme. After that, two of us independently coded the remaining entries. Next, the two coders together reviewed initial coding and attempted to resolve discrepancies. We sent those that we could not reconcile to a third member of our team to decide.

By coding the annual update statements before aligning them to the two reports, we were sure to acknowledge any efforts that had not been recommended by the Sullivan Commission or IOM. Consequently, our initial coding was more granular than the two reports. For example, the Sullivan Commission’s recommendation 4.7 advised that learners from disadvantaged backgrounds should be afforded “an array of support services, including mentoring, test-taking skills, counseling on application procedures, and interviewing skills.” We coded learning support, such as test-taking skills and mentoring, as two distinct categories. Thus, our coding produced more than one activity corresponding to a single Sullivan Commission or IOM recommendation.

Only after coding the annual update responses did we apply the principles of thematic analysis to develop a crosswalk of the FM program directors’ responses to the recommendations from the Sullivan Commission and IOM reports. 17, 18 We did this by collectively identifying those Sullivan Commission and IOM recommendations that had a theme that was parallel to our restatements of the themes. Figure 1 depicts our process. The way the themes were crosswalked is shown in Appendix Table A.

We excluded some items in the two reports and the annual updates from study because they did not relate to processes in resident recruiting. For example, the two reports recommended addressing governmental regulation, leadership development, and collaborations with community organizations. Some of the annual update statements referred to demographic characteristics. We focused only on those report recommendations or annual update activities that directly addressed resident recruiting and retaining processes.

This project was exempted from review by the Institutional Review Board of the American Institutes for Research.

The ACGME accredited 701 FM programs in 2020. Of the 701 programs, 689 (98%) provided responses to the prompt about efforts to recruit and retain diverse resident complements in the annual update. Their responses varied in terms of the number of words used to describe their efforts, how directly they responded to the prompt, the variety of efforts, and the goals to be achieved. We identified 31 unique themes in the annual updates. Twenty-three had a counterpart in either or both the Sullivan Commission and IOM reports, and another eight were unique to the annual updates. As we reviewed the crosswalk, we realized that individual themes could fit into higher-level classifications. For example, program directors indicated that they emphasized their organizations’ training in nondiscriminatory hiring policies, appointment of a DEI officer, and DEI committees. These are discreet activities that could be classified into a larger domain for organizational commitments to DEI.

Table 1 illustrates how frequently each of the restatements of the Sullivan Commission and IOM recommendations are mentioned in the annual updates.

|

Activity family

|

Synthesized restatement of activity

|

Number of programs reporting this activity

|

|

Planning and evaluation

|

Evaluation of DEI recruiting and retention efforts

Use of data for planning and progress monitoring

|

65

144

|

|

Fulfilling ethical goals

|

Residents should reflect the community and its needs

DEI objectives are related to patient care

DEI objectives are related to educational experience.

|

141

77

40

|

|

Teaching and learning

|

Learning support

Program offers curriculum in meeting needs of diverse patients.

Mentorship

Recruiting diverse faculty

Extracurricular activities

|

46

58

15

77

75

|

|

Mission

|

Program mission statement mentions DEI.

Sponsoring organization’s mission statement mentions DEI.

|

55

44

|

|

Organizational commitments

|

Training for staff, faculty, and residents on organizational DEI policy

DEI senior officer

Financial assistance

Confidential complaint reporting, ombudsman

DEI advocate at program level

DEI advocate other than senior officer

DEI committee program

|

258

23

23

6

17

67

46

|

|

Outreach

|

Pathways, pipelines

Promotions

Recruiting efforts, campus visits

Recruiting efforts at conferences and meetings

Sub-I experience

|

67

0

28

91

8

|

|

Selection procedures

|

Second language

Holistic (cultural competence) review, merit review

Recruiting committee composition

Blind recruiting

Legal compliance

Merit recruiting

|

8

169

3

57

147

105

|

Next, we discuss the themes, along with illustrative quotes. Appendix Table B provides examples from the annual update for each of the restatements.

Planning and Evaluation

Some program directors reported systematically reviewing and modifying their initiatives based on analysis of data. These data typically included the number of underrepresented minority (URM) candidates who applied or interviewed, or the results of candidate feedback surveys. For example, one program director reported, “We analyze data available from NRMP (National Resident Matching Program) and ERAS (Electronic Residency Application Service) to determine whether our recruitment efforts are effective in recruiting and interviewing a diverse applicant group.”

Fulfilling Ethical Goals

For some programs, the recruiting process was motivated by an ethical purpose, such as improving patient care, improving the educational experience, or reflecting the population served. One program director indicated,

It is our goal to train a work force of diverse, talented individuals who are prepared to provide full scope family medicine to their patients regardless of their background, lifestyle, or culture. Our institution as a whole, led by the [name of institution] Office of Inclusive Excellence, has made tremendous strides to prioritize a diverse and inclusive community and environment that is reflective of the populations we serve.

Teaching and Learning

Many programs offered a system of DEI curriculum and learning supports. That curriculum included cultural competency, second languages (medical Spanish), reflective practices, or readings about the experiences of marginalized individuals. One program director indicated,

The [institution] is continuing to expand and enhance its social medicine curriculum with more training in implicit bias, critical race theory, structural competency and critical consciousness, and systems of power and oppression. Our program has added health equity rounds four times per year to our twice monthly social medicine rounds, and we are enhancing our weekly equity case conferences.

Supports included interventions like mentoring, tutoring, or social services that encouraged the residents’ professional development. One program director summarized the array of supports:

All applicants have an individualized education plan with particular attention to providing academic support from the beginning of residency. Social and emotional needs also are evaluated and supports put in place if necessary. This support has included identifying behavioral health needs, assisting to find childcare facilities, coordinating rotations to ensure adequate time for family leave, improving space for lactation needs, providing additional temporary financial assistance, and helping residents navigate legal issues. Residents with a history of academic difficulty have an academic support plan from the first day of their residency, which is reassessed twice yearly using clinical performance and objective data such as the ITE (in-training examination), to ensure progress toward graduation and board certification upon graduation.

Mission

Many program directors wrote that the recruiting process was aligned with an institutional mission. For example, one program director indicated,

The mission of our sponsoring institution includes the education and training of underrepresented minority physicians and other healthcare professionals in the care of underserved communities. In line with this, we have focused our recruitment efforts on creating a diverse resident population.

Organizational Commitments

Program directors often wrote that their processes included a commitment of resources to advance DEI in recruiting. That may have included offsetting candidate travel costs, protecting time for DEI committee participation, training staff on nondiscrimination policy, or appointing an ombudsman to investigate claims of discrimination.

Our institution has recently named a vice president of diversity, equity, and inclusion who has formed a committee tasked with ensuring diversity and inclusion throughout the organization. As a part of this organizational movement, the GME department has formed its own diversity and inclusion council made up of the program directors of each residency program, faculty, residents from each program, and medical students who spend their third-year rotations on our campus. This group meets every other month to discuss initiatives within the GME department to promote diversity and to support equity and inclusion in our institution.

Outreach

Many programs included efforts to attract prospective residents to the field of medicine. Those efforts included pathways, or pipelines, which are systematic efforts introducing high school and college students to medicine. Outreach included updating promotional materials or recruiting at conferences. One program director reported that the institution makes

outreach to medical school deans of minority education; invites interested candidates for FM elective and subinternship experiences and psychology externships in our department; continues to support and expand engagement with minority student health education pipeline programs at [affiliated medical school] and elsewhere; leads two active and successful pipeline and mentoring programs for [city name] youth.

Selection Procedures

Selection procedures is a category of diverse initiatives. Examples include training recruiting committees on hiring policy, diversifying recruiting committees, and blinding the program to applicant demographic information in ERAS. Programs frequently used holistic review, by which applicants are credited for attributes like foreign-language fluency, perseverance, overcoming adversities, attachment to the community, or relevant experiences. Some programs integrated holistic and merit criteria. For example, one program director wrote, “The review uses a point system for letters of recommendation, research, publications, academics, life experiences, rural-community involvement, and leadership.” At the same time, many other programs construed merit criteria to include only academic qualifications, suggesting that merit is a nondiscriminatory recruiting practice. For example,

We select candidates for interview based upon demonstrated ability (USMLE Step 1 or COMLEX Part 1 passed within two attempts and within the last five years, current senior or graduate within the past 3 years, at least three months of US clinical experience) and regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, or other personal traits or status.

Appendix Table B provides examples of how program directors’ statements corresponded to the themes just described.

We found that contemporary FM programs, in our total sample, have implemented an even wider array of efforts than the Sullivan Commission or IOM recommended. Except for engaging in public awareness campaigns, all the recommendations from the Sullivan Commission and IOM have been implemented. We rostered those activities and aligned them with the Sullivan Commission and IOM recommendations, presenting a comprehensive menu of options from which to choose when identifying next steps on the journey toward a recruiting process that includes a robust array of DEI elements.

This menu can be helpful to programs because a growing body of research has demonstrated the efficacy of DEI interventions. Diversity in the learning environment has been linked to fewer experiences of discrimination and harassment against trainees. As Hartman and colleagues19 found, merit criteria, such as the US Medical Licensing Examination, COMLEX scores, or class rankings, were weakly correlated with residency performance. 19, 20 The reliance on test scores may lead to fewer URM candidates receiving invitations to interview. 21, 22

Diversity in the medical profession is important because it leads to improved patient experiences. Patients place more trust in doctors who share their racial or ethnic background, have a greater sense of partnership with their physicians, experience elevated patient satisfaction, have an enhanced understanding of their health care needs, and improve their compliance with treatment regimens. 23, 24 To achieve the goal of improving patient care, the recommendations of the two reports have been cited in the extant literature that attends to developing a more diverse health care workforce (eg, see Toledo et al 25; Bonini and Matias 26; and Velez-McEvoy 27).

The Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors Health Equity Task Force developed a DEI Competency Milestones framework, 28 which uses a rubric akin to the ACGME’s Milestones. That DEI assessment tool can help programs evaluate the degree to which faculty and residents incorporate DEI practices in learning environments and patient encounters.

This paper is a first step that may prompt further work to collate disparate research on the efficacy of various interventions aimed at diversifying the medical workforce. Medical education still needs a better understanding of the effectiveness of individual interventions, the obstacles to and facilitators of implementation, and the importance of the context of individual programs and their sponsoring organizations. Additional work would help describe how programs decide which initiatives to put into action and how applicants view these initiatives when considering their rankings for a residency match.

How completely and accurately program directors reported their DEI recruiting initiatives in the annual update is unclear. Some programs may have offered only a minimally satisfactory answer to the ACGME’s mandatory paperwork, while others may have overstated their efforts, hoping to leave a favorable impression on an accrediting agency. Program directors may have been thorough in their responses to the prompt in this reporting cycle because health and social disparities were particularly salient amid reports of police misconduct against minorities and the uneven effects of the COVID-19 pandemic during this reporting cycle. 29-32 The annual update did not prompt programs to align their efforts with the Sullivan Commission or IOM recommendations; still, we see nearly all of them being mentioned. A multiple-choice questionnaire format would more clearly quantify the use of each intervention.

The two blue-ribbon commission reports spoke more to the admissions and progress of students than to the recruitment and retention of residents. This analysis was an act of retrofitting those recommendations to align with the experience of GME. We mitigated the risk of individual interpretations misaligning those concepts first by relying on several coders who independently and then collectively coded the annual update responses, secondly by separately and then collectively aligning the Sullivan Commission and IOM recommendations, and finally by comparing the annual update responses to the recommendations.

We found that many programs have implemented recommendations from the Sullivan Commission and IOM reports. Many FM residency programs have instituted recruiting activities beyond those recommended in either of the reports. Together these sources provide a menu of options worthy of consideration by GME programs in any discipline thinking about its next steps in resident recruiting and retention.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Eric Holmboe, MD, and William McDade, MD, both of the ACGME, for offering insightful suggestions on earlier drafts of this manuscript. We would also like to acknowledge the helpful critiques of three anonymous reviewers and associate editors of Family Medicine.

References

-

Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Gaglioti AH, Liaw WR, Bazemore AW. Increasing family medicine faculty diversity still lags population trends.

J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(1):100-103.

doi:10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160211

-

Sullivan, L. Missing Persons: Minorities in the Health Professions: A Report of the Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce. Sullivan Commission; 2004.

-

Smedley BD, Stith Butler A, Bristow LR, eds. In the Nation’s Compelling Interest: Ensuring Diversity in the Health-Care Workforce. Institute of Medicine Committee on Institutional and Policy-Level Strategies for Increasing the Diversity of the U.S. Healthcare Workforce. National Academies Press; 2004.

-

-

Report of the Association of American Medical Colleges Task Force to the Inter-Association Committee on Expanding Educational Opportunities in Medicine for Blacks and Other Minority Students. Alfred P. Sloan Foundation; 1970.

-

Xierali IM, Castillo-Page L, Zhang K, Gampfer KR, Nivet MA. AM last page: the urgency of physician workforce diversity.

Acad Med. 2014;89(8):1,192.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000375

-

-

Stoesser K, Frame KA, Sanyer O, et al. Increasing URiM family medicine residents at University of Utah Health.

PRiMER. 2021;5:42.

doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2021.279738

-

Wusu MH, Tepperberg S, Weinberg JM, Saper RB. Matching our mission: a strategic plan to create a diverse family medicine residency.

Fam Med. 2019;51(1):31-36.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.955445

-

Emery CR, Boatright D, Culbreath K. Stat! An action plan for replacing the broken system of recruitment and retention of underrepresented minorities in medicine. Discussion paper, National Academy of Medicine; September 10, 2018.

doi:10.31478/201809a

-

Roulier JP, Sung J. What will it take to recruit and train more underrepresented minority physicians in family medicine? a CERA survey analysis.

Fam Med. 2020;52(9):661-664.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.453883

-

-

Brooks J, McCluskey S, Turley E, King N. The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research.

Qual Res Psychol. 2015;12(2):202-222.

doi:10.1080/14780887.2014.955224

-

Brooks J, King N. Doing template analysis: Evaluating an end-of-life care service. In:

Sage Research Methods Cases Part I. SAGE; 2014.

doi:10.4135/978144627305013512755

-

King N. Doing template analysis. In: Symon G, Cassell C, eds. Qualitative Organizational Research. SAGE; 2012:426-450.

-

Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design. SAGE; 2018.

-

-

Edgar L, Roberts S, Yaghmour NA, et al. Competency crosswalk: a multispecialty review of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education milestones across four competency domains.

Acad Med. 2018;93(7):1,035-1,041.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002059

-

Hartman ND, Lefebvre CW, Manthey DE. A narrative review of the evidence supporting factors used by residency program directors to select applicants for interviews.

J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(3):268-273.

doi:10.4300/JGME-D-18-00979.3

-

Golden BP, Henschen BL, Liss DT, Kiely SL, Didwania AK. Association between internal medicine residency applicant characteristics and performance on ACGME M

-

Boatright DH, Samuels EA, Cramer L, et al. Association between the Liaison Committee on Medical Education’s diversity standards and changes in percentage of medical student sex, race, and ethnicity.

JAMA. 2018;320(21):2,267-2,269.

doi:10.1001/jama.2018.13705

-

Jarman BT, Kallies KJ, Joshi ART, et al. Underrepresented minorities are underrepresented among general surgery applicants selected to interview.

J Surg Educ. 2019;76(6):e15-e23.

doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.05.018

-

Saha S, Shipman SA. The rationale for diversity in health professions: a review of the evidence. Health Resources and Services Administration; 2006.

-

Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce.

Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(5):90-102.

doi:10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.90

-

Toledo P, Duce L, Adams J, Ross VH, Thompson KM, Wong CA. Diversity in the American Society of Anesthesiologists leadership.

Anesth Analg. 2017;124(5):1,611-1,616.

doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000001837

-

-

-

Ravenna PA, Wheat S, El Rayess F, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion milestones: creation of a tool to evaluate graduate medical education programs.

J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14(2):166-170.

doi:10.4300/JGME-D-21-00723.1

-

Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities.

JAMA. 2020;323(24):2,466-2,467.

doi:10.1001/jama.2020.8598

-

-

-

Evans MK. Covid’s color line—infectious disease, inequity, and racial justice.

N Engl J Med. 2020;383(5):408-410.

doi:10.1056/NEJMp2019445

There are no comments for this article.