The United States has the highest maternal mortality rate among industrialized nations; the rate has risen 83% from 2018 to 2021, disproportionally impacting Black women. 1, 2 Pregnancies are increasingly complicated by hypertensive disorders, substance use, and other high-risk conditions. 3, 4 In Philadelphia, substance use is present in 58% of pregnancy-associated deaths, and pregnancy-related deaths are driven by cardiovascular disease, embolisms, infection, and hemorrhage. 5 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that 80% of maternal deaths are preventable, with timely access to primary care potentially improving outcomes. 1, 2 Family physicians are uniquely positioned to address comorbid conditions in pregnancy due to their practice scope and geographic distribution. 6-8 However, the proportion of family physicians providing obstetric care has declined dramatically. 9- 11 While over 20% of new family medicine graduates have reported an intention to practice family medicine obstetrics (FMOB), only 7% actually do. 12 Residency factors including decreased exposure to high-risk conditions and lower delivery volume contribute to this trend. 13-17 Additionally, evolving Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements for obstetrical training during residency reflect the decreasing interest in obstetrics and the challenge of providing sufficient training. 18, 19

BRIEF REPORTS

PROMOTE: An Innovative Curriculum to Enhance the Maternity Care Workforce

Jennifer D. Cohn, MD | Matthew D. Kearney, PhD, MPH | Melissa L. Donze, MPH | Caroline S O'Brien, MS | Mario P. DeMarco, MD, MPH

Fam Med. 2024;56(9):567-571.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2024.146382

Background and Objectives: Maternal morbidity and mortality disproportionally affect marginalized populations in both rural and urban settings. While the workforce of family physicians (FPs) who provide maternity care is declining, an enhanced obstetrics (OB) curriculum during residency training can help prepare future FPs to provide competent pregnancy care, particularly in marginalized communities.

Methods: We developed an innovative OB curriculum—PROMOTE: Primary care obstetrics and maternal outcomes training enhancement—in an urban underserved residency program in Pennsylvania that directly addressed barriers previously known to impact maternity care practice. We created a clinical competency assessment aligned with Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements, and we reviewed resident feedback and logs throughout and upon completion of the track.

Results: After 3 years of implementation, 23 of 48 (48%) total residents entered and/or completed PROMOTE, compared to 17 of 45 (38%) total residents who chose the OB track in the 5 years prior to implementation. Postimplementation, 29.6% of total graduates practice inpatient obstetrics, compared to 26.6% prior to implementation. Twice annual competency evaluations were completed for all residents on the track. Our review of resident submitted feedback, logs, and competency assessments suggests that the curriculum has positively impacted their knowledge, skills, and clinical care provision.

Conclusions: PROMOTE’s curricular innovation enhances obstetrical training by addressing known facilitators and barriers to practicing family medicine obstetrics. PROMOTE was implemented in an existing family medicine residency with an obstetrics track and could be adapted by other residency programs to enhance the future maternity care workforce.

Program Setting

The family medicine residency at the University of Pennsylvania is an urban underserved program with 36 residents. From July 2021 to June 2023, 470 prenatal patients and 640 obstetrical patients were cared for by family medicine residents. Roughly 10% of patients had hypertensive disorders, and 15% were diagnosed with opioid use disorder.

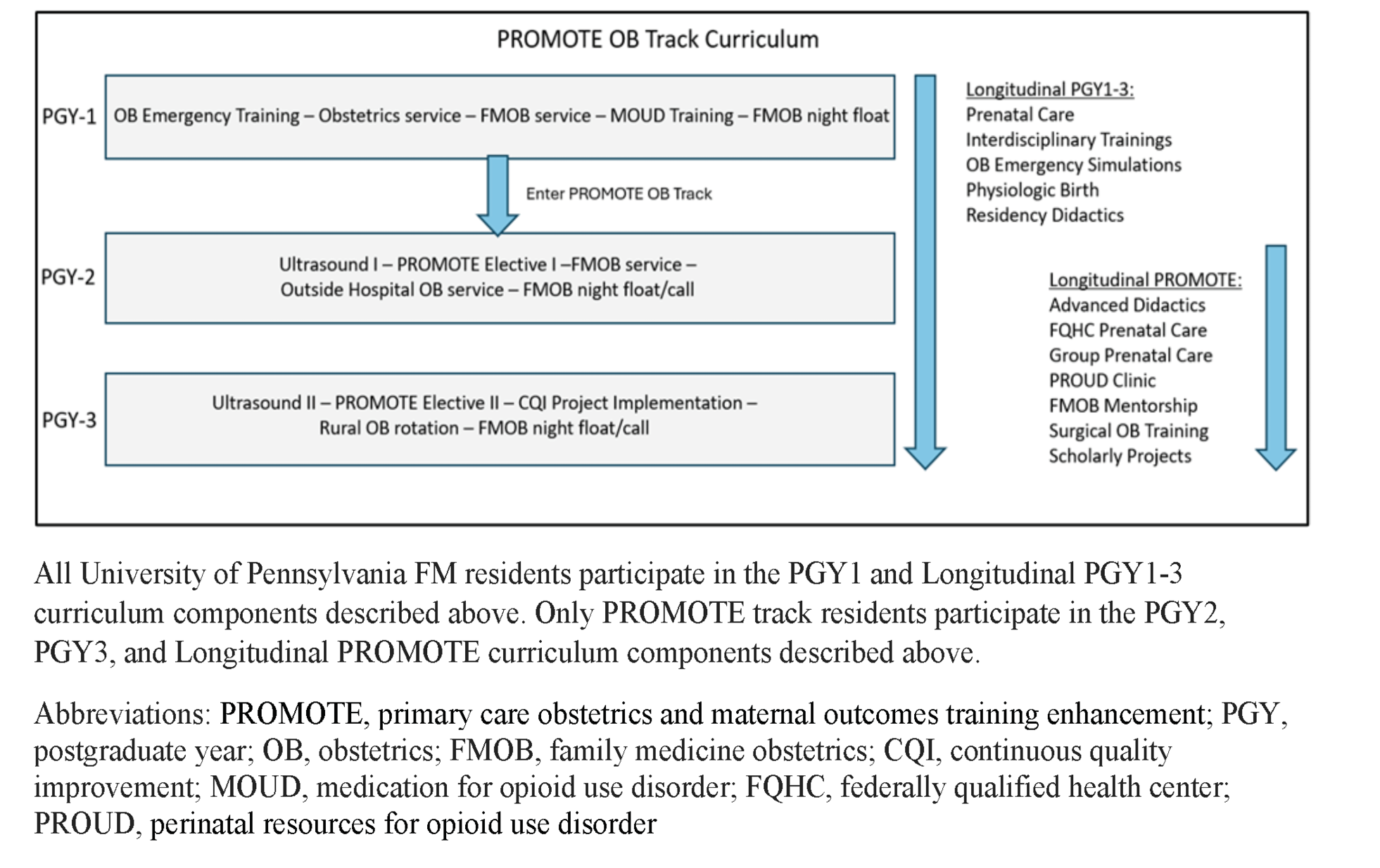

Residents select a track after postgraduate year (PGY) 1: inpatient, community medicine, or obstetrics (Appendix Table 2). Prior to the introduction of an enhanced obstetrical track within the family medicine residency, the obstetrics track entailed only additional time covering the FMOB service, without formal curriculum in surgical obstetrics, substance use, ultrasound, or outside rotations. To understand the effects of the new track on residents’ intended scope of practice, we describe implementation and learner impact of the enhanced obstetrical curriculum at our residency.

Curriculum Development

Focus group interviews with family medicine graduates from our program identified barriers and facilitators to practicing obstetrics specific to our residency and geographic setting. Several previously reported themes were reaffirmed. 13-17 Barriers included lack of mentorship, role modeling, and quality feedback; and facilitators included exposure to medical complexity, meaningful relationships with continuity patients, and collaboration with obstetricians (OB) and maternal fetal medicine (MFM) specialists.

In response to the findings from the focus groups, the authors developed PROMOTE (Primary care obstetrics and maternal outcomes training enhancement), an enhanced obstetrical track within the family medicine residency. The curriculum was designed with the following goals: (a) Improve competencies to deliver high-risk pregnancy care; (b) provide positive exposures to mentors and interdisciplinary teams; and (c) increase the rate of inclusion of maternity care in future scope of practice.

Program Implementation

Faculty members from family medicine and OB/MFM were included in curriculum implementation. Partnerships were made with local federally qualified health centers and a second affiliated hospital for additional leadership and development experience. Block and longitudinal rotations were designed to target the identified themes that support FMOB practice after graduation. Residents on the track complete curricular elements, including a PROMOTE elective that integrates high-risk care in multiple settings, a rural elective, collaborative quality improvement projects in maternal health, and integration with the perinatal resources for opioid use disorder (PROUD) clinic (Figure 1). A formalized FMOB mentorship program was established to facilitate clinical growth and career planning (Appendix Table 1).

Evaluation Plan

Residents and mentors completed two annual reviews to monitor residents’ progress toward obstetrical competency (Appendix 3). These assessments were affirmed by OB and MFM faculty liaisons and align with Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education family medicine milestones. 18 Residents also logged high-risk experiences and procedures, and provided curriculum feedback submitted in the standardized graduate medical education evaluation program used by the residency. Standardized exit interviews were performed with each PROMOTE resident upon graduation. Program outcomes, including successful integration of new curricular elements (primary) and resident scope of practice upon graduation (secondary), were recorded and tracked.

After 3 years of implementation, 23 of 48 (48%) total residents selected and/or completed PROMOTE, compared to 17 of 45 (38%) total residents who chose the OB track in the 5 years prior to implementation. Upon graduation, post implementation, 8 of 27 (29.6%) total graduates reported that they will be practicing FMOB compared to 12 of 45 (26.6%) total graduates prior to implementation.

Evaluation of resident procedure logs, competency evaluations, and graduate medical education evaluation feedback indicate that the curriculum was successfully implemented. Since the initiation of competency assessments in academic year 2023, all eligible PROMOTE residents have been evaluated twice annually for a total of 38 evaluations. Review of feedback from resident graduate medical education evaluation demonstrates positive impact on knowledge, skill, and preparedness to provide FMOB clinical care (Table 1).

|

Theme |

Curriculum components |

Postimplementation feedback* |

|

Mentorship and role modeling: Dedicated mentorship from family physicians actively practicing obstetrics provides insight, networking, and career advice. Role modeling from FMOB providers in a variety of practice settings allows for residents to understand the different ways they can practice after graduation. |

• Mentorship assignments • PROMOTE OB CCC meetings twice/year • Didactic series—FMOB career panel • Rural elective • Outside hospital rotation |

“I am definitely looking forward to the prenatal care at the FQHCs next year so I can see what that looks like” – PGY2 “Had an opportunity to experience an OB practice outside of the (health) system” – PGY3 “Rural elective has also given me greater perspective on the institutional and environment-based differences in the practice of OB, and I think it was valuable.” – PGY3 “I would prefer urban practice but am considering opening up to a more rural practice if it allowed me to do more of what I want.” – PGY3 |

|

Quality feedback and reinforcement: Longitudinal evaluation and competency assessment in a standardized fashion facilitates receipt of quality feedback and allows for continued incorporation of said feedback throughout residency training. |

• MedHub resident self and mentor evaluations twice/year • FMOB rotation evaluations aligned with ACGME competencies • Ultrasound competency assessments |

“The PROMOTE track has given me more confidence that I could work on the labor floor if I ultimately wanted to and had the opportunity and also bolstered my knowledge base with complex prenatal patients.” – PGY3 |

|

Relationships with OB/GYN and MFM: Collaborative relationships with obstetricians, both generalists and high-risk providers, facilitate positive learning experiences for residents and allow for exposure to a wide range of conditions, leading to a higher likelihood of competency in management after graduation. |

• PROMOTE I & II (MFM antepartum service, MFM diabetes clinic, high-risk clinic, antenatal testing unit, postoperative rounding, Cesarean section experience) • Outside hospital rotation with OB/GYN service • Integrated learning including didactics, simulations, and multidisciplinary trainings • Colposcopy clinic |

“I have found my time in high-risk clinic, diabetes clinic, and rounding with MFM very helpful. Certainly feel more comfortable with caring for patients with gestational diabetes and providing dietary counseling.” – PGY3 |

|

Meaningful continuity experiences: Following patients through outpatient prenatal care through labor and delivery and beyond allows for increased resident satisfaction and confidence with practicing maternity care. |

• Longitudinal placement at FQHC sites to establish community-based continuity panels • Perinatal OUD clinic continuity patients • Group prenatal care continuity patients • Consecutive days on antepartum service |

“[I’ve] gotten a lot of prenatal care experience, working hard to maximize visit continuity.” – PGY3 “More experience with MFM rounding (continuity throughout care)” – PGY2 |

|

Breadth of training vs focus on volume: Training that focuses on number of vaginal deliveries, regardless of complexity and morbidity, can limit scope of practice and comfort in providing high-risk obstetrics after graduation. |

• Didactic series components that focus on ambulatory care in prenatal and postpartum settings (OUD, LGBTQ+ reproductive health, ultrasound skills, antenatal high-risk management) • Clinical experiences—rotations at second Philadelphia hospital, FQHC, and rural setting • Population health experiences—committees, panel registry/CQI training • Operative management |

“High-risk clinics and [antenatal testing unit] time were incredibly useful. I learned the most during these sessions.” – PGY3 “I do feel that the [outside hospital] rotation and PROMOTE rotations have helped in gaining clinical knowledge.” – PGY3 “The PROMOTE curriculum due to the increased exposure to prenatal care has increased my comfort in providing prenatal care and has allowed me to be a little more aware of how to manage more common conditions in pregnancy (eg, hypertension)” – PGY3 “My PROMOTE experience is opening my eyes to the complexity of obstetrical care.” – PGY2 |

*Postimplementation feedback includes resident comments from graduate medical education evaluation.

Abbreviations: PROMOTE, primary care obstetrics and maternal outcomes training enhancement; PGY, postgraduate year; OB, obstetrics; FMOB, family medicine obstetrics; MFM, maternal fetal medicine; OUD, opioid use disorder; FQHC, federally qualified health center; CQI, continuous quality improvement; LGBTQ+, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (or questioning), other nonheterosexual people; OB/GYN, obstetrics and gynecology; CCC, clinical competency committee; ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

We successfully integrated an enhanced FMOB curriculum within our program. Thus far, implementation of the PROMOTE curriculum correlates with an increase in FMOB track selection. Additionally, despite a national decline in the proportion of residents practicing inpatient obstetrics, graduates of our residency program are increasingly practicing inpatient obstetrics upon graduation.

Track participants complete curriculum targeting causes of poor maternal outcomes, including perinatal opioid use disorder care and cardiovascular disease, directly responding to the need for comprehensive training to care for high-risk populations. 14, 15, 20, 21 Additionally, resident feedback reflects that the curriculum successfully addresses known facilitators and barriers to practicing FMOB. Integrating additional obstetrical training in varied settings while still completing other residency requirements is feasible.

Strengths

Our study had several strengths that add to the previous literature. Facilitators and barriers to practicing FMOB identified in our focus groups aligned with previously published studies and directly informed curriculum design for the PROMOTE track. 14, 15, 20 Additionally, we used a data-informed implementation process with multiple stakeholders to support a sustainable curriculum. The curriculum, which focuses on integrating knowledge and skills that address leading drivers of maternal morbidity and mortality, can be incorporated into family medicine practices without inpatient obstetrics. 3, 22, 23 The ability to shift curriculum to generalizable maternal health skills rather than delivery volume addresses a frequently cited barrier encountered in lower volume settings. 24 Few previously published studies have focused on FMOB curriculum development in residency or fellowship programs emphasizing the need for innovations such as this. 25, 26

Limitations and Next Steps

Our evaluation and implementation are limited to a single urban residency program, limiting generalizability to other programs. We may not have been able to identify all confounders or sources of bias in our analysis. Additionally, our sample size was limited due to the number of participating residents on the PROMOTE track, initiated in 2021, thus more time is needed to fully assess resident practice behavior or clinical outcomes. Finally, no standardized competency assessments exist for many of the obstetrical skills in our curriculum, so we created our own assessments and cannot make direct comparisons of competency to the preimplementation cohort.

Future work should include formal evaluation, assessment of the curriculum’s applicability to other residency programs, effect on breadth of practice upon graduation, and sustained impact over time. Family medicine also may consider adopting standardized obstetrical competency assessments for both residents and practicing physicians. 27, 28, 2 More time is needed to gather procedural logs, revise standardized competency assessments, and iterate the curriculum to achieve specific procedural competencies. Systemic barriers directly impacting the decreasing FMOB workforce, specifically limited jobs, compensation, and liability, should be the focus of further policy initiatives to improve access to maternity care.

PROMOTE is an innovative FMOB curriculum that holds promise to increase practice of maternity care by family medicine residency graduates.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling $2,996,020 with zero percentage financed with nongovernmental sources. The contents are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government. [Award number: 6 T34HP42132-02-02]

References

-

World Health Organization. Maternal and reproductive health. Accessed November 9, 2023. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/maternal-and-reproductive-health

-

Hoyert DL. Maternal mortality rates in the United States, 2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2023, doi:10.15620/cdc:124678

-

Trost SL, Beauregard J, Njie F, et al. Pregnancy-related deaths: data from maternal mortality review committees in 36 U.S. states, 2017-2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2022.

-

-

Mehta A, Hoffman R, Tew S, Huynh M-P. Improving Outcomes: Maternal Mortality in Philadelphia. Philadelphia Department of Public Health; 2020. Accessed January 2, 2024. https://www.phila.gov/media/20210322093837/MMRReport2020-FINAL.pdf

-

American Academy of Family Physicians. Facts about family medicine. Accessed November 10, 2023. https://www.aafp.org/about/dive-into-family-medicine/family-medicine-facts.html

-

Deutchman M, Macaluso F, Bray E, et al. The impact of family physicians in rural maternity care. Birth. 2022;49(2):220-232. doi:10.1111/birt.12591

-

Kozhimannil KB, Westby A. What family physicians can do to reduce maternal mortality. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(8):460-461.

-

Tong STC, Makaroff LA, Xierali IM, et al. Proportion of family physicians providing maternity care continues to decline. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(3):270-271. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2012.03.110256

-

Schlak AE, Poghosyan L, Liu J, et al. The association between health professional shortage area (HPSA) status, work environment, and nurse practitioner burnout and job dissatisfaction. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2022;33(2):998-1,016. doi:10.1353/hpu.2022.0077

-

Barreto T, Peterson LE, Petterson S, Bazemore AW. Family physicians practicing high-volume obstetric care have recently dropped by one-half. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(12):762.

-

Barreto TW, Eden AR, Petterson S, Bazemore AW, Peterson LE. Intention versus reality: family medicine residency graduates’ intention to practice obstetrics. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(4):405-406. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2017.04.170120

-

Marshall EG, Horrey K, Moritz LR, et al. Influences on intentions for obstetric practice among family physicians and residents in Canada: an explorative qualitative inquiry. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):857. doi:10.1186/s12884-022-05165-1

-

Fredrickson E, Evans DV, Woolcock S, Andrilla CHA, Garberson LA, Patterson DG. Understanding and overcoming barriers to rural obstetric training for family physicians. Fam Med. 2023;55(6):381-388. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2023.128141

-

Sutter MB, Prasad R, Roberts MB, Magee SR. Teaching maternity care in family medicine residencies: what factors predict graduate continuation of obstetrics? a 2013 CERA program directors study. Fam Med. 2015;47(6):459-465. https://www.stfm.org/familymedicine/vol47issue6/Sutter459

-

Eden AR, Peterson LE. Challenges faced by family physicians providing advanced maternity care. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(6):932-940. doi:10.1007/s10995-018-2469-2

-

Eden AR, Barreto T, Hansen ER. Experiences of new family physicians finding jobs with obstetrical care in the USA. Fam Med Community Health. 2019;7(3):e000063. doi:10.1136/fmch-2018-000063

-

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. ACGME; 2023. Accessed November 10, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/120_familymedicine_2023.pdf

-

Fashner J, Cavanagh C, Eden A. Comparison of maternity care training in family medicine residencies 2013 and 2019: a CERA program directors study. Fam Med. 2021;53(5):331-337. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.752892

-

Taylor MK, Barreto T, Goldstein JT, Dotson A, Eden AR. Providing obstetric care: suggestions from experienced family physicians. Fam Med. 2023;55(9):582-590. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2023.966628

-

American Academy of Family Physicians. AAFP-ACOG joint statement on cooperative practice and hospital privileges. Accessed November 11, 2023. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/aafp-acog-joint-statement.html

-

Oni K, Allen KC, Washington J. Prioritize comprehensive women’s health training, protect our communities. Fam Med. 2022;54(8):658-659. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2022.203722

-

Ogunwole SM, Chen X, Mitta S, et al. Interconception care for primary care providers: consensus recommendations on preconception and postpartum management of reproductive-age patients with medical comorbidities. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5(5):872-890. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2021.08.004

-

Goldstein JT, Hartman SG, Meunier MR, et al. Supporting family physician maternity care providers. Fam Med. 2018;50(9):662-671. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.325322

-

Peterson LE, Blackburn B, Phillips RL Jr, Puffer JC. Structure and characteristics of family medicine maternity care fellowships. Fam Med. 2014;46(5):354-359. https://www.stfm.org/familymedicine/vol46issue5/Peterson354

-

Helton M, Skinner B, Denniston C. A maternal and child health curriculum for family practice residents: results of an intervention at the University of North Carolina. Fam Med. 2003;35(3):174-180. https://www.stfm.org/familymedicine/vol35issue3/Helton174

-

Magee SR, Eidson-Ton WS, Leeman L, et al. Family medicine maternity care call to action: moving toward national standards for training and competency assessment. Fam Med. 2017;49(3):211-217. https://www.stfm.org/familymedicine/vol49issue3/Magee211

-

Worth A. The numbers quandary in family medicine obstetrics. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(1):167-168. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.01.170378

Lead Author

Jennifer D. Cohn, MD

Affiliations: Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

Co-Authors

Matthew D. Kearney, PhD, MPH - Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

Melissa L. Donze, MPH - Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

Caroline S O'Brien, MS - Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

Mario P. DeMarco, MD, MPH - Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

Corresponding Author

Jennifer D. Cohn, MD

Correspondence: Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.