Background and Objectives: Our objective was to describe the results of a 6-year patient-centered medical home (PCMH) transformation program in 11 Colorado primary care residency practices.

Methods: We used a parallel qualitative and quantitative evaluation including cross-sectional surveys of practice staff and clinicians, group and individual interviews, meeting notes, and longitudinal practice facilitator field notes. Survey analyses assessed change over time, adjusting for practice-level random effects. Qualitative data analysis used iterative template coding and matrix analyses to synthesize data over time and across cases.

Results: There were significant improvements in clinicians’ self-reported routine delivery of patient-centered care, team-based care, self-management support, and use of information systems (P<.0001). Clinicians and staff reported significant gains in practice change culture (P=.001). Self-reported practice-level assessments pointed to additional significant improvements in quality improvement (QI) processes, continuity of care, self-management support/care coordination, and the use of data and population management (P≤.0215). Practices and their practice facilitators reported important changes in how practices operated, significantly improving their QI processes, shared leadership, change culture, and achieving Level III PCMH NCQA Recognition. Important barriers to further progress remain, including inadequate payment models, inflexible staff roles, and difficult access to clinical data.

Conclusions: The success of these 11 primary care residency practices in making significant improvements in their delivery of patient-centered care, team-based care, self-management support, and use of information systems took time, effort, and external support. Further practice redesign for advanced primary care models will take sustained sources of well-aligned support, flexibility, shared leadership, and partnerships across residency programs for collaborative learning to assist in their transformation efforts.

In 2007, four primary care organizations formally endorsed the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) concept when they issued their Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home,1 with other organizations adding their endorsement since that time. In response, the National Commission for Quality Assurance (NCQA) released its first PCMH Recognition Program in 2008. Several other national initiatives promoted implementation of PCMH principles in primary care.1,2 Primary care professional organizations recognized the difficult-to-meet needs of both preparing the future primary care workforce while also developing current faculty in this new model of care that they had not been exposed to in their own training.3-8

In 2009, the Colorado Health Foundation sought to address these needs by funding an initial effort to transform primary care residencies in Colorado into patient-centered medical homes while teaching both faculty and residents how to lead in the new model of care. The Colorado Residency PCMH Project assisted primary care residency training practices in PCMH implementation and curriculum redesign. From 2009 through 2014, the project engaged all 10 of Colorado’s family medicine residency training practices and one internal medicine residency primary care track practice using a practice facilitation model 9-11 to transform these practices into PCMHs via practice improvement and curriculum redesign.

Models for practice improvement point to key foundational transformations—“building blocks”—as necessary components for achieving and maintaining high-performing primary care and better patient health.12-15 The Colorado Residency PCMH Project drew upon these early lessons learned, providing practices stipends, practice facilitators, biannual collaborative learning meetings, evaluation support, curriculum guidance, and access to consultation tools and resources. Many of the changes practices worked on focused on improving core components of a PCMH: leadership, quality improvement (QI) processes, staff and resident engagement, team-based care, patient access, data systems, patient engagement, and care coordination.

More than 10 years have passed since the Joint Principles were issued and 9 years since the PCMH project began in Colorado. What has changed in our residency training programs and practices? This article reports on results from the evaluation from baseline through final follow-up of the project (2009 through 2014).

A total of 11 residency practice sites from 10 residency programs participated in the Colorado Residency PCMH Project (one program has two practice sites). All 10 of Colorado’s family medicine residency training practices participated in the collaborative since its inception in 2009. One primary care internal medicine residency training practice joined the collaborative in 2012. Each practice was paired with a trained practice facilitator (previously known in the project as a Quality Improvement Coach) from a nonprofit organization, HealthTeamWorks. The practice facilitator attended monthly practice QI meetings, providing training, guidance, support, and resources for practice transformation, and helped practices work to achieve National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) PCMH Recognition.16 The residency programs also received support to revise their residency training curriculum to better integrate PCMH competencies and training opportunities.17 Representatives from each residency, including faculty, residents, and staff members, also attended collaborative learning sessions focused on implementation of PCMH and practice improvement twice per year.

A parallel qualitative and quantitative evaluation included practice questionnaires, staff and clinician questionnaires, resident clinician questionnaires, and several qualitative data sources, including field notes, meeting notes, and interviews. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approved this evaluation project as exempt from human subjects review.

Practice Surveys

Changes in practice over time were assessed using three surveys that aligned with both components of the PCMH and with the facilitation support and resources provided to the residency practices. The surveys were administered at baseline (prior to practice coaching), midpoint (Fall 2012), and endpoint (Fall 2014).

- The PCMH Clinician Assessment (PCMH-CA) provided information about clinicians’ routine use of the PCMH components as part of patient care.17 The PCMH-CA was completed by faculty clinicians and residents. The survey assessed clinicians’ perceived regular use of PCMH components using a 5-point Likert-type scale on 35 items. Prior validation and factor analysis yielded four reliable subscales used in our analysis: Team-based Delivery System Redesign, Patient-centered Care, Self-management Support, and Information Systems.17

- The Practice Culture Assessment (PCA) provided practice-wide information about the practice culture related to practice change and improvement.18 The PCA was completed by faculty providers, residents, administrators, and staff using a 5-point Likert-type scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree) on 22 items. Prior validation and factor analysis yielded three reliable subscales used in our analysis: Improvement and Change Culture, Work Relationships, and Chaos.18

- The PCMH Practice Monitor (see Appendix: https://journals.stfm.org/media/2359/fernald-appendixa-fm2019.pdf) was designed for this project to provide practices with a way to concretely analyze their implementation of different PCMH domains: Leadership, Staff and Resident Engagement, QI Team Functioning, Registry and Measures, Population Management, Patient-Centered Care, Team-based Care, Coordination of Care, Access and Scheduling, and Integration of Mental and Behavioral Health. Each practice completed one Monitor twice per year in a team meeting facilitated by the practice facilitator to consider how fully each PCMH component had been implemented in the practice. Items were developed by a team of physicians, researchers, and practice facilitators experienced in practice transformation to reflect key activities and milestones within the PCMH model. The version used in this project included between five and seven items for each PCMH domain, with each item identifying a specific milestone for the PCMH, for a total of 55 items. Each item was scored from 0 to 10. Zero meant that there was no activity or that the item was not at all implemented; 10 meant that an item was completely implemented. Principal factor analysis was used to assess the Monitor items. Since we wanted to allow for positive correlations among domains, we used the oblique promax rotation (a kind of oblique rotation that allows factors to be correlated and can be calculated fairly quickly). Five factors with 32 items were retained as determined by the proportion criterion (at least 75%) which uses cumulative proportion of common variance explained by factors, explaining 76% of the common variance. Cronbach α was computed for each factor to confirm internal consistency as follows: Quality Improvement Process (α=0.8909), Team-based Care (0.8131), Data and Population Management (0.9095), Self-management Support and Care Coordination (0.8651), and Continuity of Care (0.7610). See Appendix A (https://journals.stfm.org/media/2359/fernald-appendixa-fm2019.pdf) for the final factor “subscales” and items.

The sample of practice survey data selected for this report was designed to align with the three phases of funding: baseline (initial funding in 2009), midpoint (end of funding period one in 2011), and endpoint (end of funding period two in 2014). This is aligned with a consistent practice facilitation delivery model, which was maintained across these 6 years of funding. To improve interpretability across surveys, all scores were rescaled from 0 to 100 before beginning analysis. Subscale scores were then computed for each survey and used as outcome variables in the analysis of change over time. For each subscale, a mixed-effects longitudinal (general linear mixed models) analysis examined change over time using all available data between 2009 and 2014. A random effect was included for practice to account for clustering of individuals within practices. Because it was not possible to link individual respondents over time, the structure of the data is longitudinal at the practice level with individuals nested within practices. For the PCMH-CA and PCA subscale scores, time was coded as “period” and analyzed as an ordinal variable (baseline, midpoint, end) to assess overall change over time. Role (resident vs faculty or clinician vs staff) was included as a fixed effect to assess for overall differences in scores by role, along with a two-way interaction term (role x time) to determine whether change over time differed by role. For the Monitor subscale scores, time was coded continuously (time since baseline, converted to fraction of a year to aid interpretability); estimates were obtained for slopes (average change per year) to assess the magnitude of change over time. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Field Notes and Interviews

The evaluation incorporated several qualitative data sources over multiple years of the project: practice facilitator field notes, resident exit interviews, learning collaborative presentations, practice facilitator lessons learned sessions, and summative, semistructured group key informant interviews with each practice near the end of the evaluation.

The team used a combination of analytic approaches to answer key questions of interest to practices and the evaluation team. All qualitative documents were loaded into ATLAS.ti (Version 7.5; Scientific Software Development, GmbH, Berlin, Germany, 2014) for analysis. Members of the evaluation team read and reread qualitative data, utilizing a combination of an editing style of coding (inductive codes emerged from the reading of the data) and a template style of coding (a priori codes corresponding with key evaluation questions were applied to data), while allowing other key themes to emerge.19 For example, we applied major a priori codes of “barriers” and “successes” to evaluation data throughout analysis to quickly segment data for further inductive coding. We conducted subsequent rounds of inductive coding to identify specific barriers and facilitators to PCMH transformation, such as “provider and staff engagement,” “electronic health record documentation and reporting,” and “leadership.” Over the course of the project, members of the evaluation team and practice facilitators developed case-based matrices20 to organize summary data and refine major themes within each practice as well as those arising across multiple or all practices, periodically reviewing matrices and discussing emerging themes as a group. The evaluation team regularly presented findings to participants for discussion and feedback using the following strategies: (1) periodic review of findings and lessons learned with practice facilitators who were in all sites; (2) sharing of results at scheduled learning collaboratives with resident and faculty clinicians and staff, and (3) a final summary case report based on the survey and interview data was shared with each practice at the conclusion of the project.

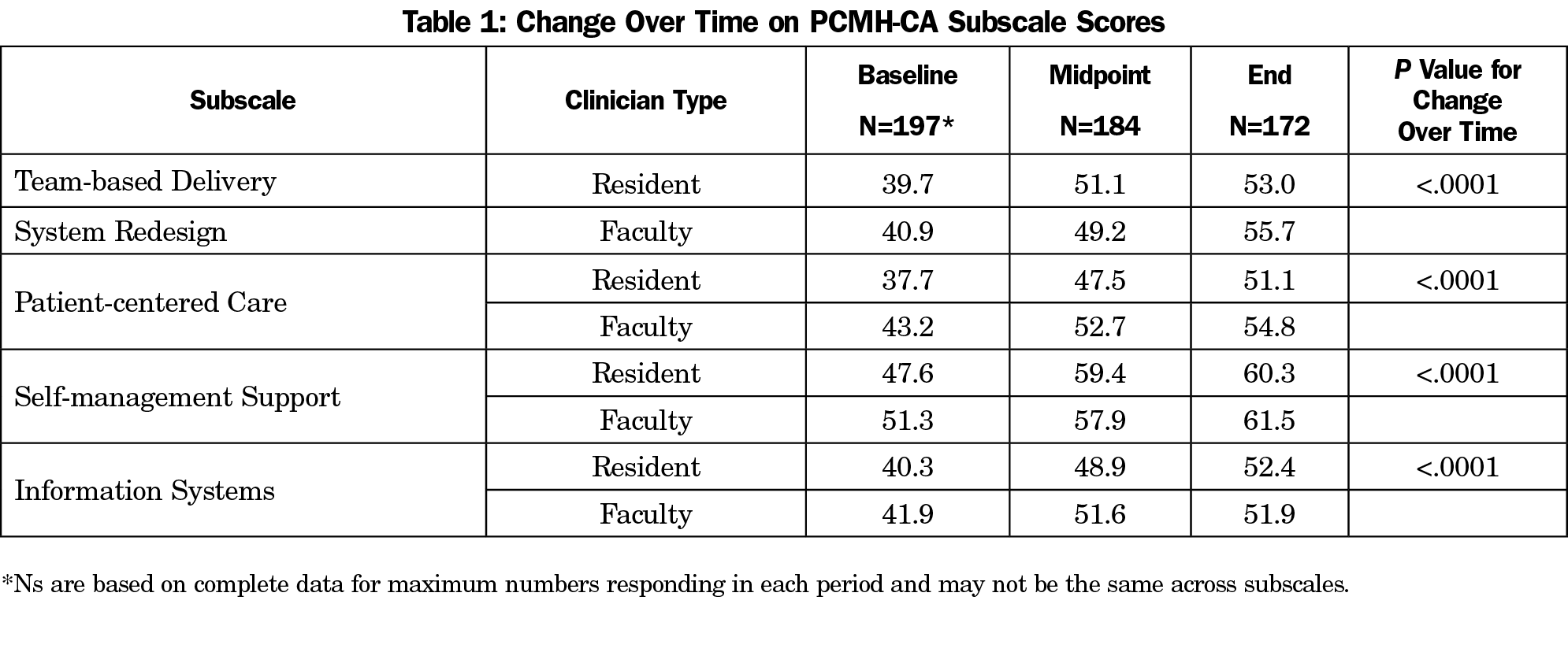

PCMH Clinician Assessment (PCMH-CA)

Over time, clinicians’ self-reported routine use of PCMH components improved significantly (P<.0001) across all four PCMH-CA subscales—team-based delivery system redesign, patient-centered care, self-management support, and information systems—for both resident and faculty clinicians (Table 1). Only in patient-centered care were there significant differences between resident and faculty clinicians, with resident clinicians reporting less patient-centered care at baseline (P=.0088). There was no difference in change in scores over time between resident and faculty clinicians.

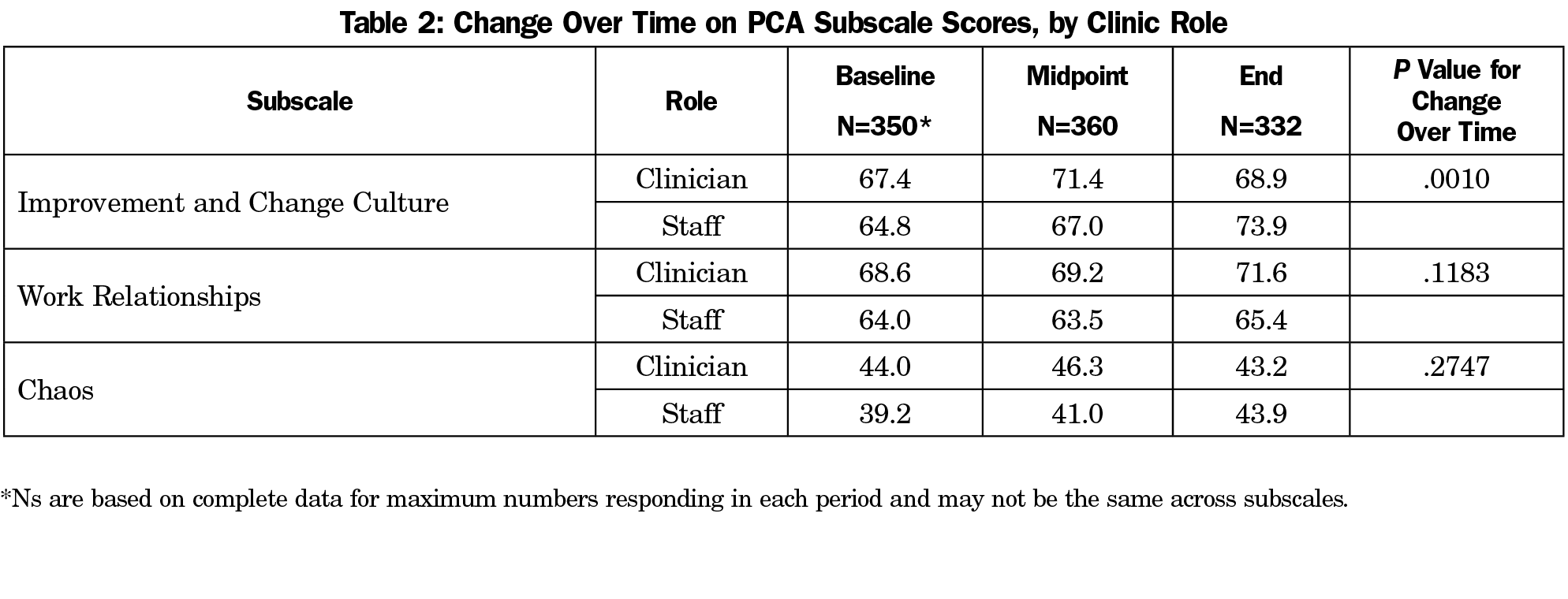

Practice Culture Assessment (PCA)

On the PCA, difference over time, after adjusting for clustering of respondents within practices, clinicians, and staff reported significant overall improvements in the improvement and change culture in their practices (Table 2). Overall changes in work relationships were not statistically significant. Practice chaos remained relatively unchanged overall. However, there were significant differences between roles, with staff reporting lower overall scores on improvement and change culture (P=.0025), chaos (P=.0230), and work relationships (P=.0002).

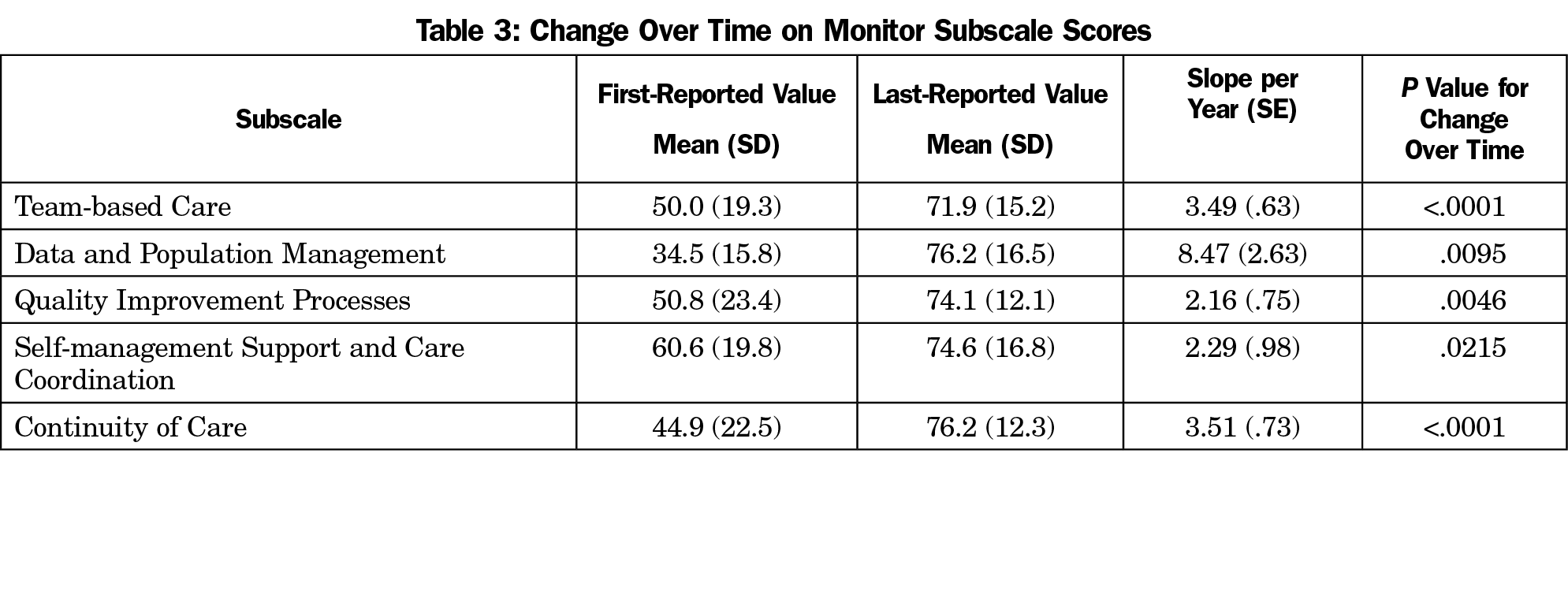

Practice Monitor (Monitor)

Overall, practices reported improvements in all areas of the Monitor. Subscales for Team-based Care(P<.0001), Data and Population Management (P=.0095),QI Processes (P=.0046), Continuity of Care (P=.0023), Self-management Support (P<.0001) and Care Coordination (P=.0215) showed significant improvements between 2009 and 2014 (Table 3).

Qualitative Data

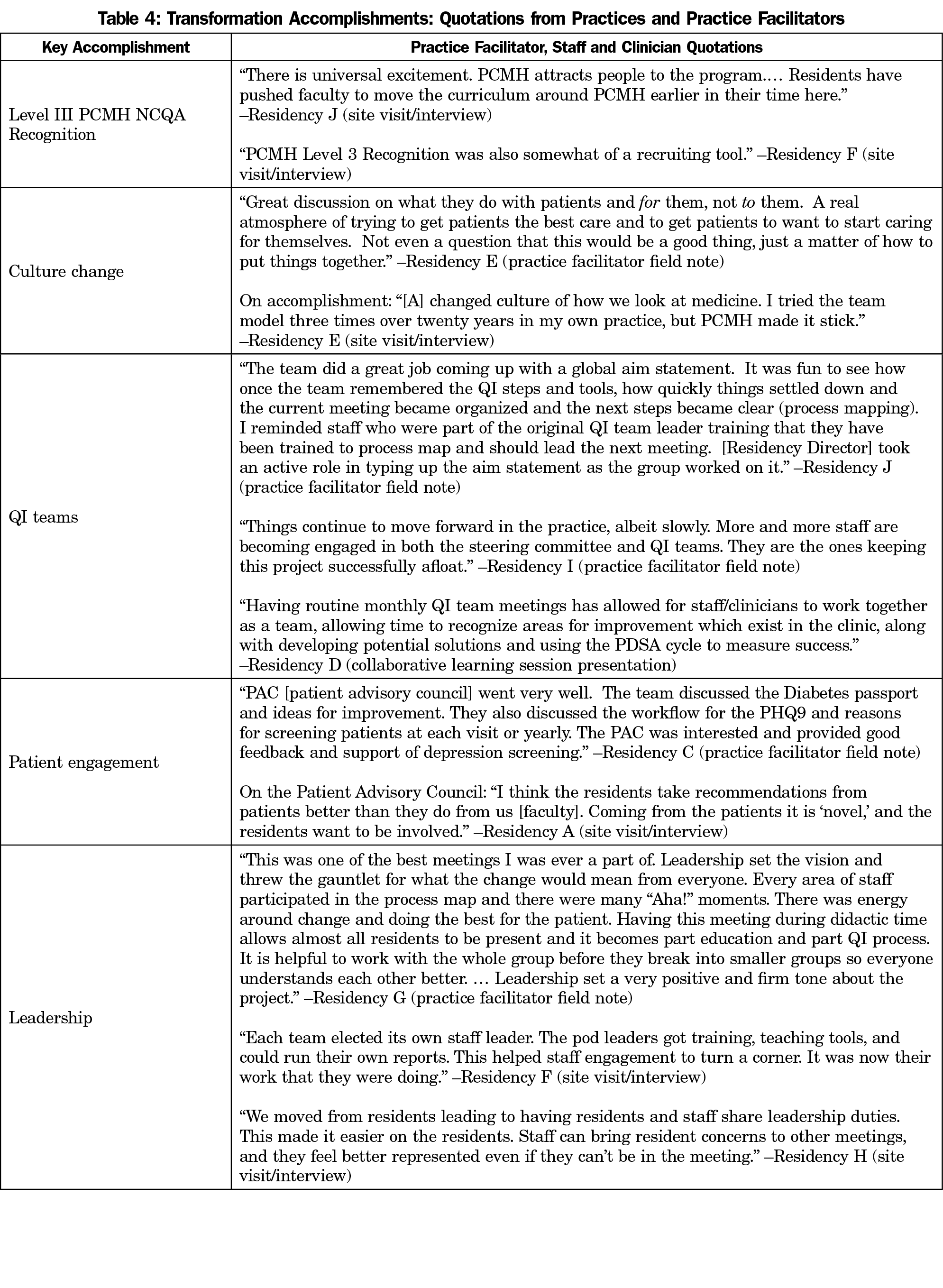

The practice facilitator field notes described 11 different stories of the practice transformation journey. There was no single or easy path to transformation. For some, foundational changes came early, only to suffer setbacks later. For others, the foundational changes were beleaguered by early resistance and barriers, but practices found their way forward later.

Facilitator field notes detailed over the 6 years many of the successes, struggles, highs, lows, and accomplishments of these practices (see Table 4 quotations). Key among the accomplishments were:

- Level III PCMH NCQA recognition (highest recognition level) for all practices;

- Improved practice cultures to support team-based care and patient-centered operations;

- The establishment and maintenance of effective QI teams;

- Patient engagement efforts including data collection on patient experiences and satisfaction, new educational materials and communication methods, and patient and family advisory councils;

- Shared leadership across the project, including leadership roles for staff and residents and alignment of residency QI projects with practice-focused QI projects.

Leadership engagement appeared to be essential for gaining buy-in from staff and residents, although not all formal leaders in all practices were open to change in leadership style and a shift to informal leaders implementing quality improvement projects.

Group key informant interviews were conducted with members of each practice at the end of the final funding cycle in 2014, asking practice staff and clinicians to reflect on their accomplishments, leadership changes, and most important lessons learned. Overall, the residencies agreed that the project had helped them accomplish the following notable practice improvements:

- Improved practice cultureand leadership, including more team-based care, better team engagement especially among staff, active management of change fatigue, and increased shared leadership with residents and staff;

- Better practice processes (workflow improvements, use of data and registries, and more patient outreach efforts);

- Addition of QI efforts and defined roles (eg, care managers, data/IT manager, team leaders).

Most practices thought that resident engagement in QI work and teamwork had improved, although this was uneven across practices. Among the commonly mentioned positive outcomes of their participation, all practices noted achievement of Level III NCQA PCMH recognition, and most were able to point to specific improvement projects that led to better patient outcomes, such as improved health assessment and screening, lower hospital readmission rates, and improved patient satisfaction.

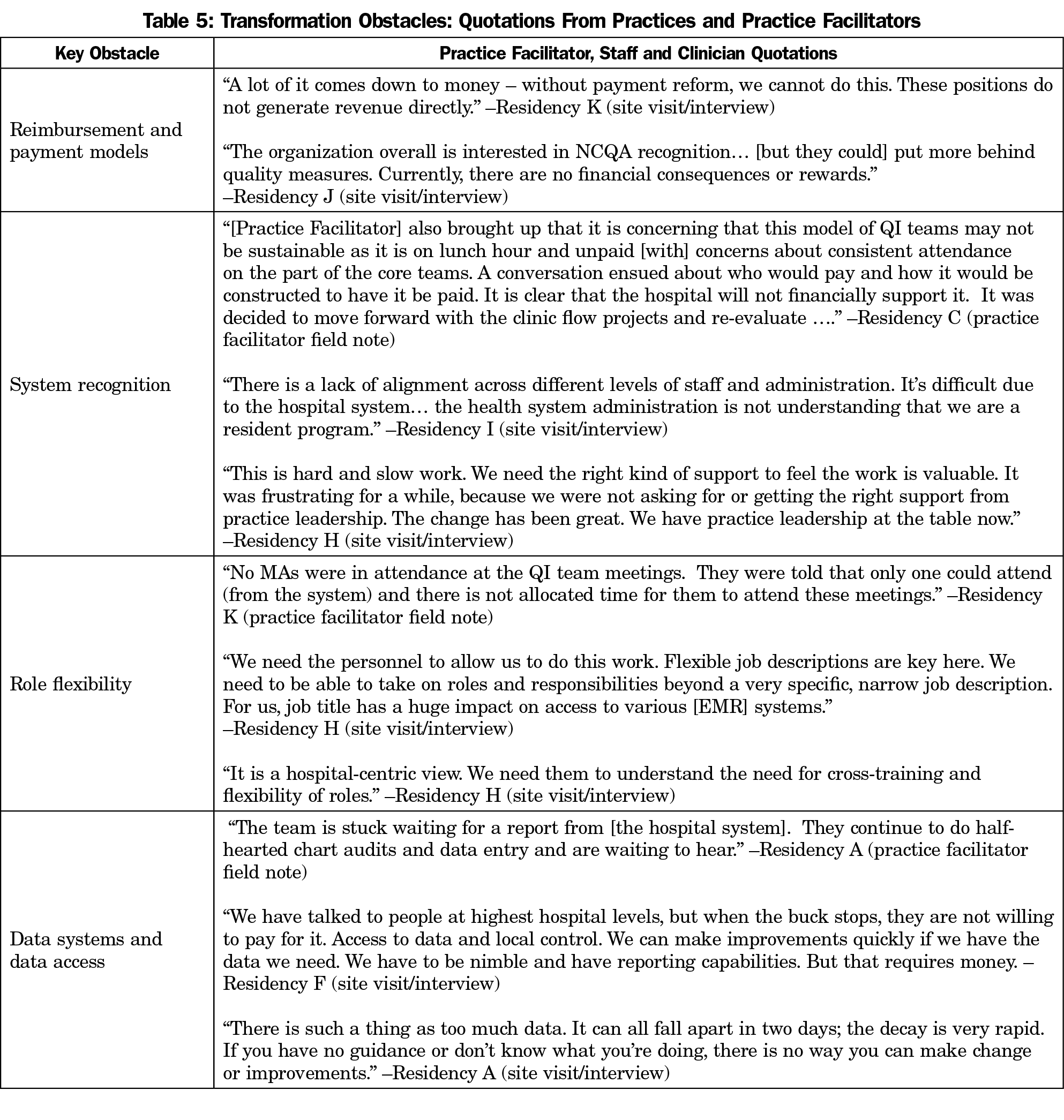

These were hard won changes (see Table 5 quotations). Facilitator field notes reflected the following common obstacles that had to be overcome by all residency practices:

- Few reimbursement and payment models for interactions and patient care outside of exam room or clinic walls;

- Lack of system recognition of practices’ progress and successes, and the time required to start and maintain PCMH efforts;

- Little system allowance for flexible roles and duties, especially for staff, including new job descriptions for key staff that would allow them to practice at the top of their license;

- Poor clinical data access and data systems, with electronic health records (EHRs) that did not provide key data for quality improvement and population management.

Project residency practices also expressed the following common lessons learned:

- Both administrative and physician leadership have to be trained and engaged in transformation work. Faculty members who lacked experience with change concepts were often resistant to teaching these concepts.

- Alignment of hospital and practice priorities and educational curriculum to support transformation are all necessary for true success.

- Continued spread of transformation methodologies, theories, and frameworks are essential for everyone to be bought into the process, especially staff and clinicians working together. Often, turnover of key leadership and staff could halt improvements and transformation.

- Connecting the resident-led QI projects mandated for graduation by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education to practice priorities increased sustainability of the work.

Practices indicated that practice facilitation played an essential role in helping them work through their NCQA recognition process while providing external accountability for maintaining focus and follow-through on quality improvement activities. Additionally, practice facilitators who were flexible in their approach, addressed culture and change fatigue, and addressed the priorities and uniqueness of each practice were most successful in implementing change.

From 2009 to 2014, faculty clinicians, resident clinicians, and practice staff who participated in the Colorado Residency PCMH Project reported significant improvements in their routine delivery of patient-centered care, team-based care, self-management support, and use of information systems. Self-reported practice-level assessments also pointed to significant improvements in team-based care, continuity of care, and the use of data and population management. In terms of care processes, these practices made important overall improvements in foundational components of PCMHs, delivering more patient-centered, team-based care, while improving their use of clinical data.

Meanwhile, these practices reported important changes in operations, significantly improving their QI processes and their culture around improvements and change. Importantly, the level of chaos reported in these practices remained relatively unchanged despite attempting to make substantial cultural and operational changes amid variable hospital system support,21 known barriers to change,22 clinician and staff turnover, and ongoing and well-known challenges of EHR installations, transitions, or upgrades.23-26 Several obstacles persisted during the project that may have slowed important PCMH changes: ill-aligned reimbursement or payment models, lack of system recognition of the need for flexible staffing and timed need for PCMH transformation, and lack of access to clinical data for quality improvement. These resonate with summary findings from the Preparing the Personal Physician for Practice (P4) project that noted that simultaneously improving continuity clinic and residency education is disruptive, takes time, and can be done, though running a clinic and innovating requires financial help.8

Practices valued the practice facilitation and other support they received, believing that the support assisted them in the changes they made. Practice facilitation addressed attributes that are unique to residency practices that required flexibility, managing resistance, and familiarity with curriculum16 to support successful transformation. The residency practices recognized that complexities in their structure require long-term efforts that engage more permanent staff and faculty in shared leadership opportunities—in addition to residents—in improvement efforts and change processes. This evaluation was not designed to assess the long-term sustainability of practice transformation activities resulting from facilitation support as delivered in this intervention; however, the residency programs found value in shared learning activities and continued the biannual collaborative learning sessions without grant funding following the end of the project.

Although this sample of residency training programs made progress on important practice culture and operations measures in delivering better patient-centered care, the evaluation was not able to assess changes in other important outcomes such as the patient experience, cost, clinical outcomes, and provider satisfaction. Although we did not directly assess provider and staff resiliency or burnout, the results from the PCA survey were encouraging in that overall practice chaos was unchanged amid new PCMH activities and change culture improved. The PCA results also point to potential areas for further work to improve work relationships (which improved, but were not significant) and address an apparent gap between high ratings of practice culture by clinicians compared to staff.

Implementation of PCMH and other advanced primary care models in residency programs and practices is essential in preparing the workforce of the future for emerging payment models. Findings indicate that primary care practice transformation, including increased self-rated capacity for data use and patient-centered and team-based care delivery, can be accomplished in residency training settings through practice facilitation and other targeted support. Practices attributed aspects of successful change to project support, which highlights the value of external practice facilitator roles and collaborative learning approaches. Observed practice improvements are relevant to primary care’s continued movement toward patient-centered and value-based models of care.15,27 Capacity in these areas is particularly important in residency practices, which are responsible for training future primary care providers. While we believe these Colorado residency programs are now well-positioned to deliver on the quadruple aim, future evaluations will need to address patient, population, cost, and provider outcomes for these redesigned training programs.

The success of these 11 primary care residency practices in making important and significant improvements in their delivery of patient-centered care, team-based care, self-management support, and use of information systems took time and effort. External support provided through the Colorado Residency PCMH Project helped faculty, resident clinicians, and staff make meaningful steps toward delivering more advanced models of primary care. This study elucidates that further practice redesign for advanced primary care models will take sustained sources of well-aligned support, shared leadership, flexibility, and partnerships across residency programs for collaborative learning to assist in their transformation efforts.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kim Marvel, PhD (former executive director of the Colorado Association of Family Medicine Residencies) and Nicole Deaner, MSW (former HealthTeamWorks practice facilitator for the Colorado Residency PCMH Project) for their outstanding support and dedication to the participating residency practices and this evaluation.

Portions of the results of this manuscript were presented at the STFM Conference on Practice Improvement, December 5, 2015, Dallas, TX.

Financial Support: The Colorado Health Foundation provided funding for this work.

References

- American Academy of Family Physicians; American Academy of Pediatrics; American College of Physicians; American Osteopathic Association. Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/pcmh/initiatives/PCMHJoint.pdf. Published March, 2007. Accessed February 5, 2019.

- Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Stange KC, Stewart EE, Jaen CR. Summary of the National Demonstration Project and recommendations for the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8 Suppl 1:S80-90; S2. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1107

- Carney PA, Eiff MP, Green LA, et al. Transforming primary care residency training: a collaborative faculty development initiative among family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatric residencies. Acad Med. 2015;90(8):1054-1060. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000701

- Carney PA, Eiff MP, Saultz JW, et al. Aspects of the Patient-centered Medical Home currently in place: initial findings from preparing the personal physician for practice. Fam Med. 2009;41(9):632-639.

- Eiff MP, Waller E, Fogarty CT, et al. Faculty development needs in residency redesign for practice in patient-centered medical homes: a P4 report. Fam Med. 2012;44(6):387-395.

- Task Force 1 Writing Group; Green LA, Graham R, et al. Report of the task force on patient expectations, core values, reintegration, and the new model of family medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:33-50.

- Clay MA II, Sikon AL, Lypson ML, et al. Teaching while learning while practicing: reframing faculty development for the patient-centered medical home. Acad Med. 2013;88(9):1215-1219. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829ecf89

- Carney PA, Eiff MP, Waller E, Jones SM, Green LA. Redesigning Residency Training: Summary Findings From the Preparing the Personal Physician for Practice (P4) Project. Fam Med. 2018;50(7):503-517. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2018.829131

- Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Stewart EE, et al. Effect of facilitation on practice outcomes in the National Demonstration Project model of the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8 Suppl 1:S33-44; S92. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1119

- Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW, Aspy CB. Practice facilitators: a review of the literature. Fam Med. 2005;37(8):581-588.

- Rhydderch M, Edwards A, Marshall M, Elwyn G, Grol R. Developing a facilitation model to promote organisational development in primary care practices. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7(1):38. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-7-38

- Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511-544. https://doi.org/10.2307/3350391

- Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1775-1779. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.14.1775

- Solberg LI. Improving medical practice: a conceptual framework. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(3):251-256. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.666

- Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard-Grace R, Grumbach K. The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):166-171. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1616

- Buscaj E, Hall T, Montgomery L, et al. Practice Facilitation for PCMH Implementation in Residency Practices. Fam Med. 2016;48(10):795-800.

- Jortberg BT, Fernald DH, Dickinson LM, et al. Curriculum redesign for teaching the PCMH in Colorado Family Medicine Residency programs. Fam Med. 2014;46(1):11-18.

- Dickinson WP, Dickinson LM, Nutting PA, et al. Practice facilitation to improve diabetes care in primary care: a report from the EPIC randomized clinical trial. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(1):8-16. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1591

- Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications; 1999.

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2014.

- Knierim K, Hall T, Fernald D, et al. Effects of hospital systems on medical home transformation in primary care residency training practices. J Ambul Care Manage. 2017;40(3):220-227.

- Fernald DH, Deaner N, O’Neill C, Jortberg BT, degruy FV III, Dickinson WP. Overcoming early barriers to PCMH practice improvement in family medicine residencies. Fam Med. 2011;43(7):503-509.

- Fernandopulle R, Patel N. How the electronic health record did not measure up to the demands of our medical home practice. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(4):622-628. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0065

- Ajami S, Arab-Chadegani R. Barriers to implement Electronic Health Records (EHRs). Mater Sociomed. 2013;25(3):213-215. https://doi.org/10.5455/msm.2013.25.213-215

- O’Malley AS, Draper K, Gourevitch R, Cross DA, Scholle SH. Electronic health records and support for primary care teamwork. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22(2):426-434. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocu029

- Miller RH, Sim I. Physicians’ use of electronic medical records: barriers and solutions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;23(2):116-126. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.23.2.116

- Ellner AL, Phillips RS. The Coming Primary Care Revolution. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):380-386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3944-3

There are no comments for this article.