Background and Objectives: Competency-based medical education (CBME) has been incorporated into graduate medical education accreditation and is being introduced in undergraduate medical education. Family medicine (FM) faculty at one institution developed a CBME FM clerkship to intentionally maintain the integrity of FM specialty-specific teaching during their institutional CBME curricular revision.

Methods: From the five FM domains (Access to Care, Continuity of Care, Comprehensive Care, Coordination of Care, and Contextual Care), 10 competencies and 23 FM educational activities (EAs) were defined. The set of EAs encompasses the wide scope of care available to FM clerkship students. Students complete four required EAs (preventive care, care transitions, chronic disease management, and acute care) and select four additional EAs matching their interests. EA selection frequency and course evaluations were assessed for the first cohort of learners (N=156; February 2016-July 2017).

Results: The most frequently selected EAs were: information coordination, procedures, and care of the family. The least selected were: patient e-communication, end-of-life care, and shared medical decision making. Student perceptions of the experience were strong prior to and after implementation.

Conclusions: Having both required and selective EAs ensures a robust FM experience tailored to students’ interests. The FM CBME curriculum allowed comparable clinical experiences despite variations in clinical sites and preceptor scope. Because of its breadth, FM is uniquely suited to address multiple competencies; this demonstrates the educational value of required FM clerkships to institutional leaders interested in implementing CBME curriculum. The CBME framework can provide a structure for more intentional student-clinic assignments based on EAs available at specific sites.

Competency-based medical education (CBME) is an outcomes-based educational movement seeking to improve graduate quality and preparedness. CBME was introduced to graduate medical education (GME) in the late 1990s when the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) introduced the six domains of clinical competency. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) later developed a list of Core Entrustable Professional Activities (Core EPAs)1 that define a set of behaviors expected of all medical school graduates.2 In 2013, CBME formally became a part of the GME accreditation process, basing program accreditation decisions on defined educational outcomes.3 There is also a national movement underway to improve the transition from undergraduate medical education (UME) to GME,4 including how to best provide competency-based assessments about medical school graduates to program directors.5 However, while there are defined milestones for competency assessment and expectations for residents,6 these criteria are still emerging for UME.

In 2014, our institution launched a transformed UME curriculum with revised structure, content, pedagogy, and assessments.7 This included the implementation of a CBME framework across the entirety of a student’s education and the introduction of 43 institutional competencies. As a part of this, each clerkship was asked to identify at least four of the institutional competencies to assess.

The curriculum transformation provided an opportunity to reevaluate the family medicine (FM) clerkship learning objectives from a CBME perspective, ensuring that students learn the philosophy of our specialty and the role family physicians play in the medical system. We anticipated a number of challenges including selecting the core competencies of FM, creating a framework for the implementation of educational and assessment interventions across a variety of clinical practices, and ensuring a high-quality educational experience for all learners despite a dispersed model of teaching clinics across a large area of urban and rural practices. Ultimately, we developed and assessed competencies specific to our FM clerkship in addition to incorporating assessment of several of our institution’s competencies. To avoid overburdening clinical faculty with assessments, the team utilized reflective competency in which written submissions are used to demonstrate students’ level of competence.8

We report how we created our FM-specific competencies, decided which institutional competencies to include, describe the creation of “educational activities,” and show preliminary outcome and satisfaction-level data. This experience can inform similar efforts as other schools incorporate CBME in their curricular reforms.

The FM Clerkship Workgroup anticipated the possible risk of losing the specialty-specific essence of family medicine through overintegration of institutionally-derived, nonspecialty-specific assessments as well as the potential trap of trying to assess too many disparate competencies at once, overwhelming learners and faculty. To avoid this, our team first defined what was most important to the specialty of family medicine. The workgroup then identified domains and experiential competencies specific to our specialty. In grappling with the question of what is most important in our broad specialty, the five domains of FM as described in the Textbook of Family Medicine9 (Access to Care, Continuity of Care, Comprehensive Care, Coordination of Care, and Contextual Care) were used as the starting point. The team’s guiding principles in this work were: (1) Maintain a robust clinical experience with the breadth and depth of FM, (2) Demonstrate student exposure to the essence of FM to increase their skills and knowledge, and (3) Ensure individualized but comparable experiences between learners and clinical sites.

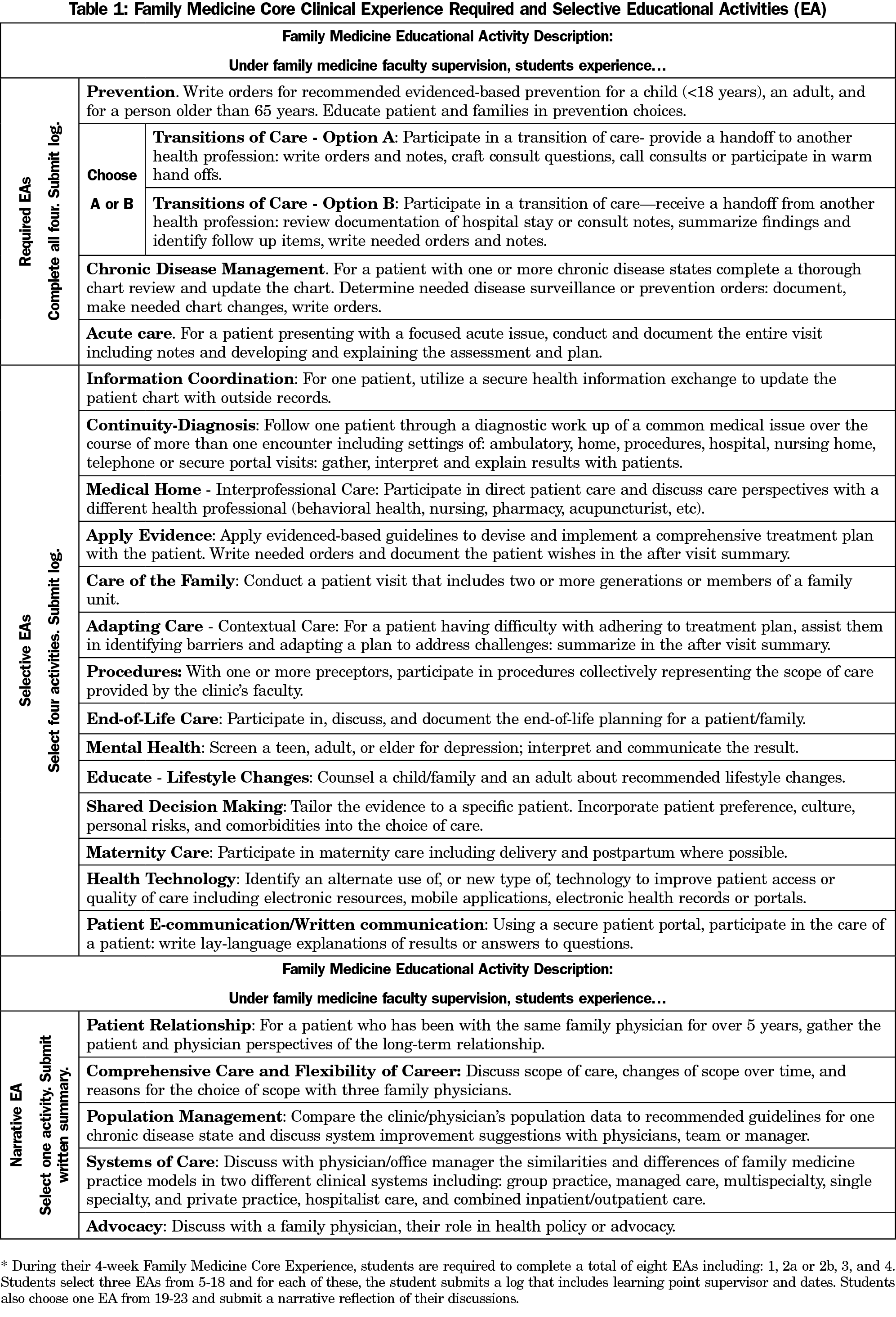

The group identified two FM-focused experiential competencies for each of the above five domains and then defined a set of educational activities (EAs). EAs represent specific, actionable units of work that a student must complete. Table 1 reflects the 23 EAs and descriptors for each. The outcome-focused language of the FM EAs was synched with the outcomes-focused School of Medicine competencies such that institutional curricular needs were met without losing the essence of the clerkship experience.

The final list was created in an iterative process including feedback from wider local and national FM educator audiences.10 For example, for the FM domain of Coordination of Care, the student experiential competency is to experience how family physicians facilitate coordination of care during provider-to-provider transitions. EA2, which relates to this experiential competency, requires students to participate in a handoff with another health professional. As a set, the 23 EAs represent the range and variety of the practice of family medicine. Based on the University of Michigan’s competency-based health training program,11 a table available on the STFM Resource Library (https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/extending-competency-based-educatio?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments?tab=librarydocuments&CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a) was created that allowed students to track their EAs and demonstrate experiences within each of the five domains of FM.

During the 4-week required FM clerkship, students must complete four required core EAs (Table 1, EAs 1-4), a minimum of four additional selective EAs (Table 1, EAs 5-18), and one selective narrative EA (Table 1, EAs 19-23). The selective EAs account for variability in scopes of practice available at any given clinical site and allow learners to tailor the clerkship by selecting experiences they feel would be most valuable to their own professional development and career plans. Students are responsible for documenting completion of their EA selections on a learning management system utilized by our university (MedHub “procedure log”12) and recording brief learning points for each (on another system, Sakai13). The narrative EAs require students to explore an aspect of care with their supervising faculty and demonstrate reflective learning. The narratives are submitted on Sakai and are reviewed by the course director using criteria associated with that competency. Students are allowed to alter their EA choice if their assigned clinical site does not support their initial selections.

We intentionally first defined FM competency using the EAs, and only afterward addressed the selection and measurement of institutional competencies. This allowed us to frame the institutional specialty-agnostic competencies. The work group found that any of the 43 institutional competencies could be assessed or attained within the FM experience. The four institutional competencies selected were those which our course was well positioned to measure: (1) Contribute to electronic health records (EHR), (2) Provide telemedicine consultation, (3) Demonstrate evidence-based care, and (4) Self-assess strengths, deficiencies, and limits. In parallel to the EA development, we revised clinical workshops, educational goal setting, narrative self-reflections, and a formative objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) to further capture the FM competencies and to accrue additional data points for assessment of the selected competencies. For example, a previously existing OSCE case that focused on the skills necessary for a telehealth encounter14 provided a natural opportunity to assess an institutional telemedicine competency. Similarly, an EHR workshop was revised to better measure the institutional EHR competency.

After implementing this CBME framework and resultant course changes, the team studied the impact on learners’ experiences in four ways:

- We evaluated which EAs were selected.

- We compared global pre- and postcourse rating averages using the standardized end-of-rotation course evaluations.

- We gathered qualitative student feedback via a focus group with each cohort of students without the course director present. Feedback on the curriculum and course were gathered and comments were transcribed and anonymized.

- We evaluated the frequency of students needing to change their selective EAs due to an inability to achieve the EA at their clinical location.

Our Institutional Review Board approved the study.

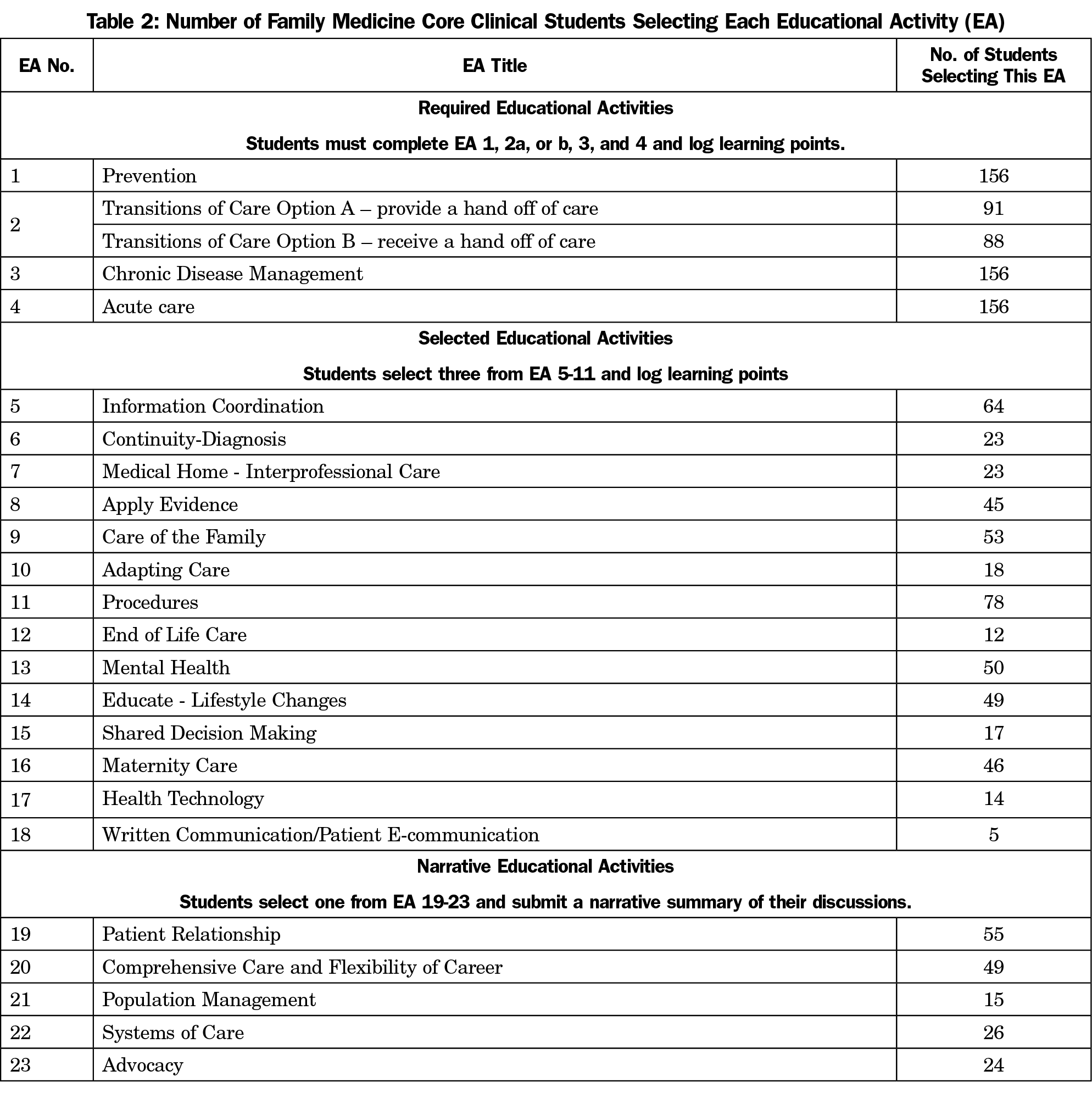

Implementation began in February 2016. As of July 2017, 156 learners had completed the FM Clinical Experience. Table 2 reports the number of students who chose each EA. EAs 1-4 are required, and EA2 offers Options A and B. Some students chose to do both, thus the total students completing EA2 exceeds 156.

The three selective EAs chosen most frequently were: Information Coordination (EA5), Procedures (EA11), and Care of the Family (EA9). The three selective EAs chosen least frequently were: Patient E-communication (EA18), End-of-Life Care (EA12), and Shared Medical Decision Making (EA15). Of the five written reflective EAs, the most frequently selected was Patient Relationship (EA19).

The implementation of the FM competency-based curriculum did not alter the clinical course student ratings. The year prior to the change (2014-2015) the clerkship had an average global 4.4/5 rating on the prompt “Rate the quality of your educational experience in this clerkship.” Following implementation, the average rating had dropped to 4.1/5 and as of June 2017, ratings returned to 4.4/5 and have remained similar. Of the 156 students, seven (4.5%) altered their EA list.

Feedback from focus groups indicated that the EA framework was initially difficult to understand and came across as busywork rather than intentional, guided learning. Additionally, students assigned to work in practices with a more limited scope of clinical practice appreciated the EA focus, while those working with physicians with a broader-scope clinical practice found the EAs less beneficial.

Many UME institutions are implementing CBME curricula, through the adoption of the AAMC’s EPAs15 and/or institutionally-derived competencies. The challenges of CBME implementation are real,16 though projects are ongoing to help close the gap between UME and GME.17 For FM educators, CBME curricula can present both opportunities and threats. The value that the FM clerkship provides in providing opportunities to meet institutional competencies can underscore the importance of the FM clerkship to MD programs. CBME frameworks such as the use of EAs can provide a scaffold to ensure a rich, learner-centered experience across clinical sites, a common language to evaluate learners and objective information toward ensuring that graduates are residency-ready learners. The greatest potential threats are losing the essence of FM by attempting to divide the specialty’s complex relationships and care into measurable competencies and the risk of administrative overload on learners and faculty.

The FM clerkship provides students comprehensive, rich, clinical learning experiences and offers numerous opportunities for exposure to and assessment of a variety of student competencies. We found that nearly all of our institution’s 43 competencies could be assessed during the FM clerkship. This allowed us to select institutional competencies for the FM clerkship which other clerkships found difficult to measure; this demonstrated the value of the FM Clerkship to educational leaders and potentially created good will toward the department. When undergoing change, framing is critical for both for learners and teachers. The EA framework is a guide for a learner-centered FM CBME experience. Initially, we did not adequately emphasize the practical benefits of the EAs to learners. Instead, we emphasized their usefulness as an assessment tool for tracking course progression, which benefits the course director and may help support grade differentiation. Student feedback allowed us to streamline EA documentation and alter our orientation to emphasize the positives for learners, presumably resulting in the recovery of strong course ratings. For learners, the selection and submission of the EAs should be described as an exercise in learner-centered goal identification. We also now explain the use of EAs as a practical guide for what students should do on a day-to-day basis and for what opportunities are available in FM. From a faculty perspective, the resultant EA list now more clearly defines experiences germane to FM that were always present but potentially underappreciated.

For educators, this set of EAs should be viewed as a faculty development tool. Clinical preceptors need to know what is expected of learners, and what opportunities should be provided. We used the EA lists to teach faculty and residents how to frame their clinical teaching, and to demonstrate ways students can add value to patient care. For example, with EA2b, a student is tasked with reading and interpreting a hospital discharge summary, documenting medication and diagnoses changes and needed follow up care and testing, and placing needed orders. These experiences can improve patient transitions and decrease preceptor workload.

Empowering learners to select EAs allowed for individualization while ensuring they are broadly exposed to the variety of FM care. Providing experiences that align with interests may have implications for student perceptions of the rotation and specialty, potentially leading to more students discovering family medicine as a good fit for a future career choice.18 Students are asked to select EAs prior to their first day at their assigned clinics, so choices reflect their educational desires. Although they may alter their choices based on the population or scope of care available, only seven of 156 students have made changes.

Students are required to log only the EAs they selected, so the number of EAs recorded does not reflect the summation of all experiences. Informal discussion and comments have suggested that students “complete” far more EAs within their rotation. For example, 78 of the students chose the EA on procedures, yet course evaluations show that far more students experience procedures.

A table correlating each FM EA with the 43 institutional competencies (available upon request) has allowed the course director to more easily select additional course competency assessments as needed by the institution without creating more work. The course director has utilized selective EAs to add a competency that correlates to those EAs. The framework allows for the flexibility to provide needed institutional/general competency assessments.

Locally, the EA competency-based framework’s utility continues to evolve in our FM clerkship. Our institution has a dispersed model where students are assigned to different clinics across a large area of urban and rural practices. In assigning students to clinical practice locations, we aim to match the strengths of an individual practice with the educational goals of individual learners. We anticipate that EA data can eventually be used in this process by building a database of selected EAs that have been completed at each site, helping us know what is already available at our clinical practice locations. Alternatively, the EA list can be brought to current and potential clinical teaching sites for preceptors to identify which activities they can routinely ensure a student will be able to experience during their rotation and provide a clear framework for us to state the expectations of a clinical teaching site. This will also assist with the Liaison Committee on Medical Education19 requirements to standardize education of a required rotation across multiple teaching sites.

Nationally, as both the practice of medicine and our learners rapidly change, the EA data collection helps inform what students want from their experience (as opposed to simply what is currently offered). Implementation and analysis of experiences at other institutions would help develop a universal list of opportunities that could be especially valuable for institutions with short- or underresourced FM experiences. EA data collection is useful both as a way of helping students find visiting rotations where they could obtain opportunities elsewhere and as a way of demonstrating to their school that other institutions are able to offer more.

The AAMC Core Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) for Entering Residency1 will likely be the framework for future CBME transformations.* In this model, entrustment decisions are based on the level of supervision, different from the skill-based concepts of the competencies as described elsewhere.20 It is important to note it is often difficult to deem a resident entrustable, and nearly impossible to do so for students. While some student behaviors may be a proxy measurement of entrustment, entrustment requires a relationship allowing observation of consistent performance in varied settings and situations over time and that may be more than what our current model of clinical education allows.

The FM Clerkship EA work has created a path to provide evaluative data points towards entrustability when a UME institution moves from competency-based assessments to overall entrustment decisions. Because the EAs can be mapped to AAMC Core EPAs, completion of the EAs can provide valuable information for a future entrustment committee regarding the AAMC EPAs. For example, in completing the required FM EAs, students provide care (under supervision) through writing orders, consenting patients, performing handoffs, engaging in shared decision making, working with interprofessional teams, finding and interpreting test results, and finding and applying guidelines. This is complementary to performing the typical activities of history and physical exam, note writing and presenting orally. Documentation of these experiences will be necessary but not sufficient for ensuring that graduates of CBME curricula are competent to enter into residency. One of the greatest challenges all educators face in the era of CBME is how we assess competencies and define where learners should be across the UME, GME, and CPD continuum.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is one of the first comprehensive attempts of an FM clerkship to incorporate CBME in this manner. Future research on student performance and understanding of the specialty would be valuable. This curricular approach can be adapted by other specialties and institutions as a framework for intentional education in an evolving CBME system. There is an opportunity to share best practices and allow future and larger research around the efficacy of the competencies and EAs in preparing learners for the FM ACGME Milestones21 they will encounter.

EPAs are units of professional practice, defined as tasks or responsibilities that trainees are entrusted to perform unsupervised once they have attained sufficient specific competence.1

Acknowledgments

The authors are immensely grateful to Nicole Deiorio, MD, for providing an outside perspective on this work and her suggestions in the late stages of manuscript revision.

References

- Obeso V, Brown D, Phillipi C, et al. Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering Residency: Toolkits for the 13 Core EPAs. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2017. https://www.aamc.org/download/482214/data/epa13toolkit.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2018.

- Englander R, Cameron T, Ballard AJ, Dodge J, Bull J, Aschenbrener CA. Toward a common taxonomy of competency domains for the health professions and competencies for physicians. Acad Med. 2013;88(8):1088-1094. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829a3b2b

- Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):1051-1056. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1200117

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Initiatives - Transition to Residency. https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/485662/transitiontoresidency.html. Accessed June 6, 2018.

- Sozener CB, Lypson ML, House JB, et al. Reporting Achievement of Medical Student Milestones to Residency Program Directors: An Educational Handover. Acad Med. 2016;91(5):676-684. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000953

- Holmboe ES, Edgar L, Hamstra S. The Milestones Guidebook. Chicago: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2016. http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/MilestonesGuidebook.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2018.

- Mejicano GC, Bumsted TN. Describing the Journey and Lessons Learned Implementing a Competency-Based, Time-Variable Undergraduate Medical Education Curriculum. Acad Med. 2018;93(3S Competency-Based, Time-Variable Education in the Health Professions):S42-S48. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002068 P

- Hodges BD, Lingard L. The Question of Competence : Reconsidering Medical Education in the Twenty-First Century. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press; 2014.

- Saultz J. Chapter 1: An Overview and History of the Specialty of Family Practice. In: Saultz J. Textbook of Family Medicine, 1st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1999.

- Palmer R, Biagioli F, O’Neill Pe, et al. EPAs and Competencies: Placing UME Family Medicine in a Competency-Based Framework. Presentation at 2016 STFM Conference on Medical Student Education, Phoenix, AZ, January 28-31.

- University of Michigan. Curriculum: Master of Health Professions Education (MHPE) Curriculum. https://medicine.umich.edu/dept/lhs/education/degree-programs/master-health-professions-education-mhpe/curriculum. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- MedHub (software). Minneapolis, MN. https://www.medhub.com/. Accessed September 12, 2018.

- Apereo Foundation. Sakai (software). https://sakaiproject.org/. Released 2014. Accessed September 12, 2018.

- Palmer RT, Biagioli FE, Mujcic J, Schneider BN, Spires L, Dodson LG. The feasibility and acceptability of administering a telemedicine objective structured clinical exam as a solution for providing equivalent education to remote and rural learners. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15(4):3399.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering Residency. 2014. http://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/CoreEPACurriculumDevGuide.pdf. Accessed October 16, 2016.

- ten Cate O, Scheele F. Competency-based postgraduate training: can we bridge the gap between theory and clinical practice? Acad Med. 2007;82(6):542-547. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31805559c7

- Carraccio C, Englander R, Gilhooly J, et al. Building a Framework of Entrustable Professional Activities, Supported by Competencies and Milestones, to Bridge the Educational Continuum. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):324-330. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001141

- Burack JH, Irby DM, Carline JD, Ambrozy DM, Ellsbury KE, Stritter FT. A study of medical students’ specialty-choice pathways: trying on possible selves. Acad Med. 1997;72(6):534-541. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199706000-00021

- Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Standards and Publications. http://lcme.org/publications/#Standards. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- Ten Cate O. AM last page: what entrustable professional activities add to a competency-based curriculum. Acad Med. 2014;89(4):691. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000161

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. The Family Medicine Milestone Project. 2015. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/FamilyMedicineMilestones.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2017.

There are no comments for this article.