Introduction: Structural racism is a root cause of health disparities. While family medicine residency programs recognize the importance of addressing race in medicine, it is unclear how many programs have established racial justice training (RJT). This study examines residents’ views on the current state of RJT in their respective programs.

Methods: This survey was part of the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) 2021 national survey of family medicine residents. Questions addressed RJT, resident reported barriers to implementing such training, and recommendations for change.

Results: Of the family medicine residents who responded (n=266), the majority of individuals (91.5%) and their residency programs (65.0%) stated that addressing racism in medicine is an educational priority. Residents reported a minority of their programs (17.3%) have a longitudinal curriculum. Residents who received RJT in residency are more likely to be in communities of color (P=.03). The top requests included recruiting faculty and residents of color, and establishing community-based partnerships.

Conclusions: Few residencies have been able to implement RJT to the extent that residents desire. Lack of curricular time and faculty training were commonly cited barriers. Strategies to address these barriers and implement RJT across residencies are needed to combat structural racism.

Racism continues to be heavily present in the health care system, leading to profound harm for people who access and work within it. Medical students and residents have had multiple calls to action about addressing racism in medicine and the need for systemic change.1-4 Combating the effects of racism requires the use of innovative and impactful curricula to facilitate change at all levels of education and leadership.1, 5-7

Racial justice curriculum (RJC) focuses on the understanding of the cause and consequences of racism and its effects on health disparities.8,9 The shift from cultural competency to racial justice training (RJT) enables individuals to identify racism as it is experienced and focus on transforming the structural aspects of medicine that lead to health disparities. The reality of how such curricula are prioritized and implemented across residencies is unclear. A survey of family medicine residency program directors concluded that although a majority of program directors believed that RJC should be included in the curricula, only 30.7% of residency programs had implemented formal RJC.10

Our study examined residents’ opinions and perceptions of the current state of RJT within family medicine residency programs (FMRPs), and their perspectives on barriers to implementation. We hypothesized that while most family medicine residents believe it is an educational priority to address racism in medicine, only a minority of FMRPs will have RJT. Furthermore, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) residents and residents who train in communities of color will more likely agree that RJT should be a priority.

Data were gathered and analyzed as part of the 2021 Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine residents. The methodology of the CERA Resident Survey has previously been described in detail.11 Resident members of the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) received the survey electronically in spring 2021. The project was approved by the American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board.

We performed all analyses using STATA 13.1 (STATA Corp, College Station, TX). We conducted univariate statistics to describe resident and program characteristics. We performed bivariate statistics to examine the relationships between RJT with resident and program characteristics. We used χ2 tests to assess significance for categorical comparisons. We set significance at P<.05.

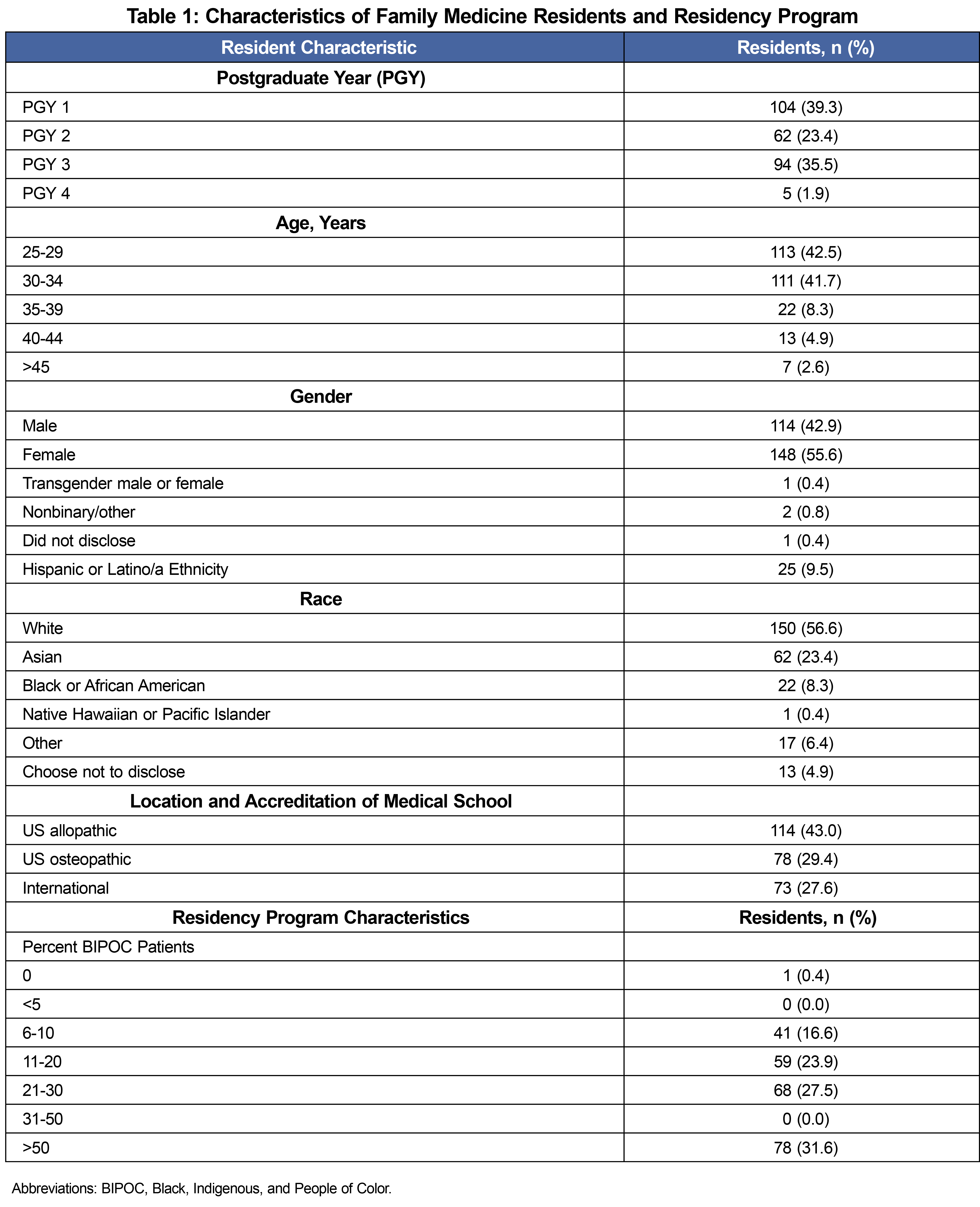

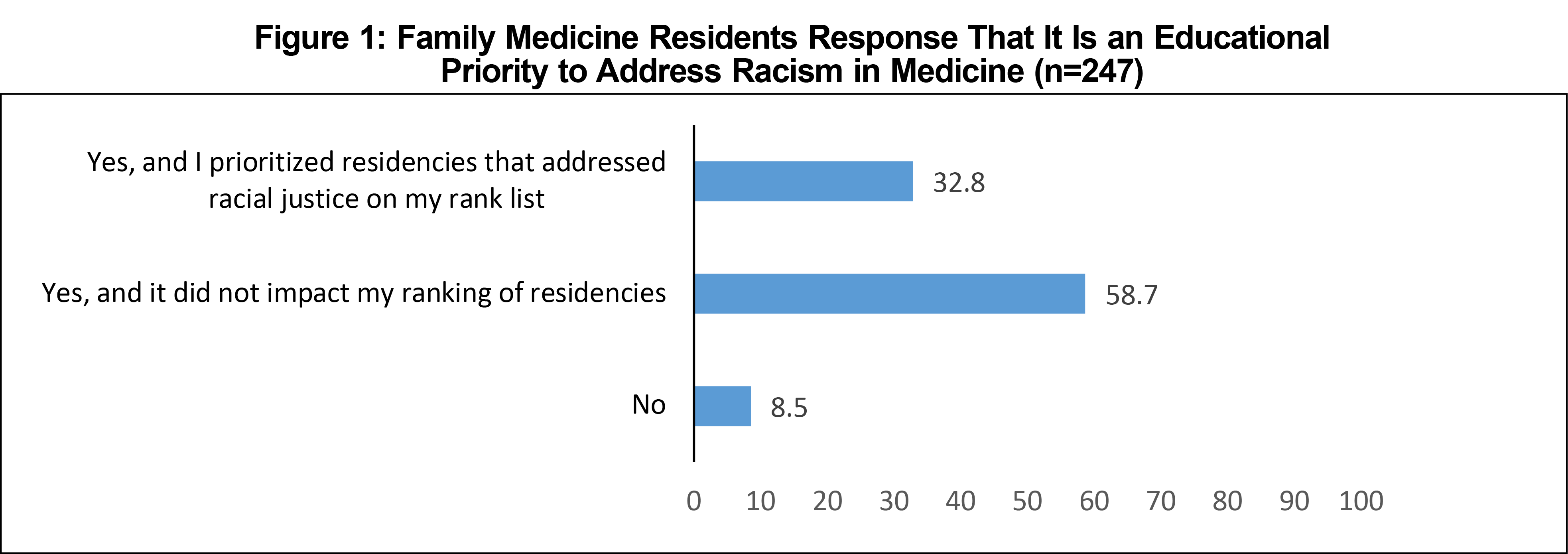

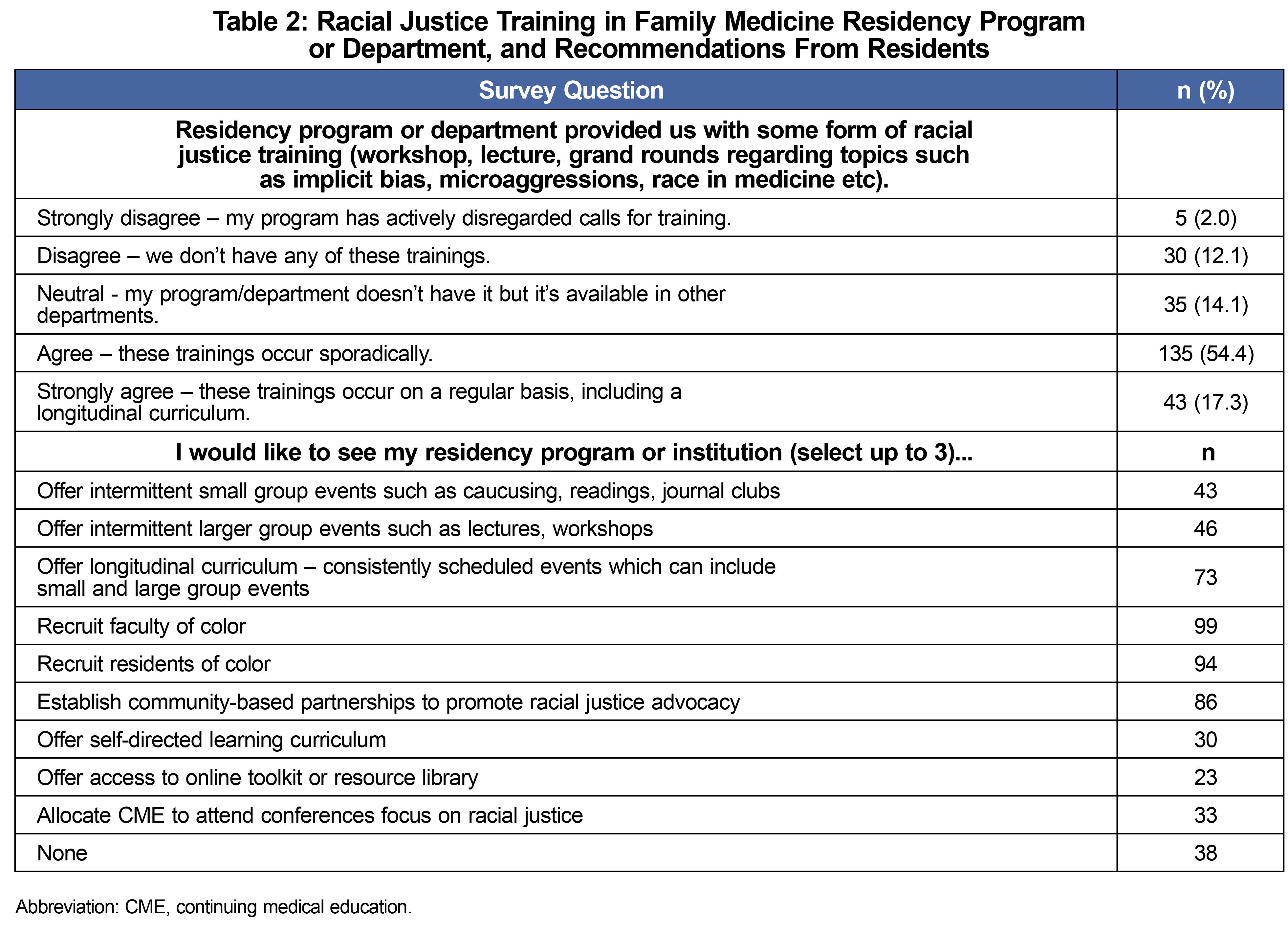

A total of 266 residents participated in the CERA survey. Table 1 lists participant characteristics including their demographic breakdown. Of the residents who responded, a majority (91.5%) believed that addressing racism in medicine is an educational priority, and 32.8% prioritized ranking residencies higher if the program's mission aligned with this (Figure 1). Although BIPOC residents were more likely to respond that RJT should be an educational priority, the difference with non-BIPOC residents was not significant (P=.059). Sixty-five percent of residents believed that their FMRP stated addressing racism in medicine is an educational priority. However only 17.3% of residents believed their programs had regularly scheduled trainings (Table 2).

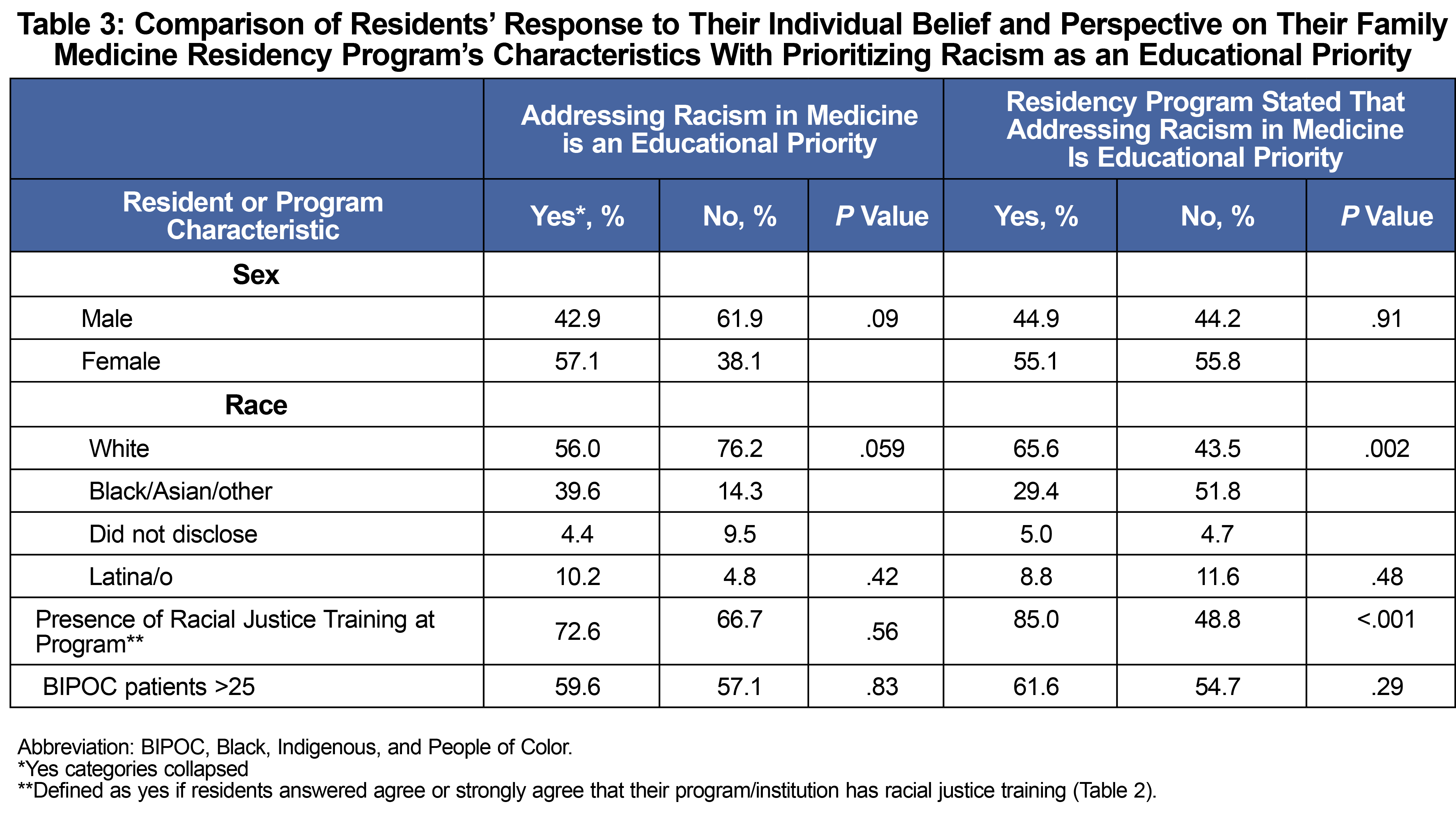

Table 3 shows predictors of which residents and FMRPs were more likely to agree that addressing racism was an educational priority. For residents, there were no significant correlation based on demographics nor training environment. Residents who believed that their FMRP identified racism in medicine as an educational priority were significantly more likely to have RJT (85.0% vs 48.8%, P<.001). Residents from FMRP that serviced a higher percentage of BIPOC patients (>25%) were also more likely to have RJT (Table 4, 63.8% vs 48.6%, P=.03).

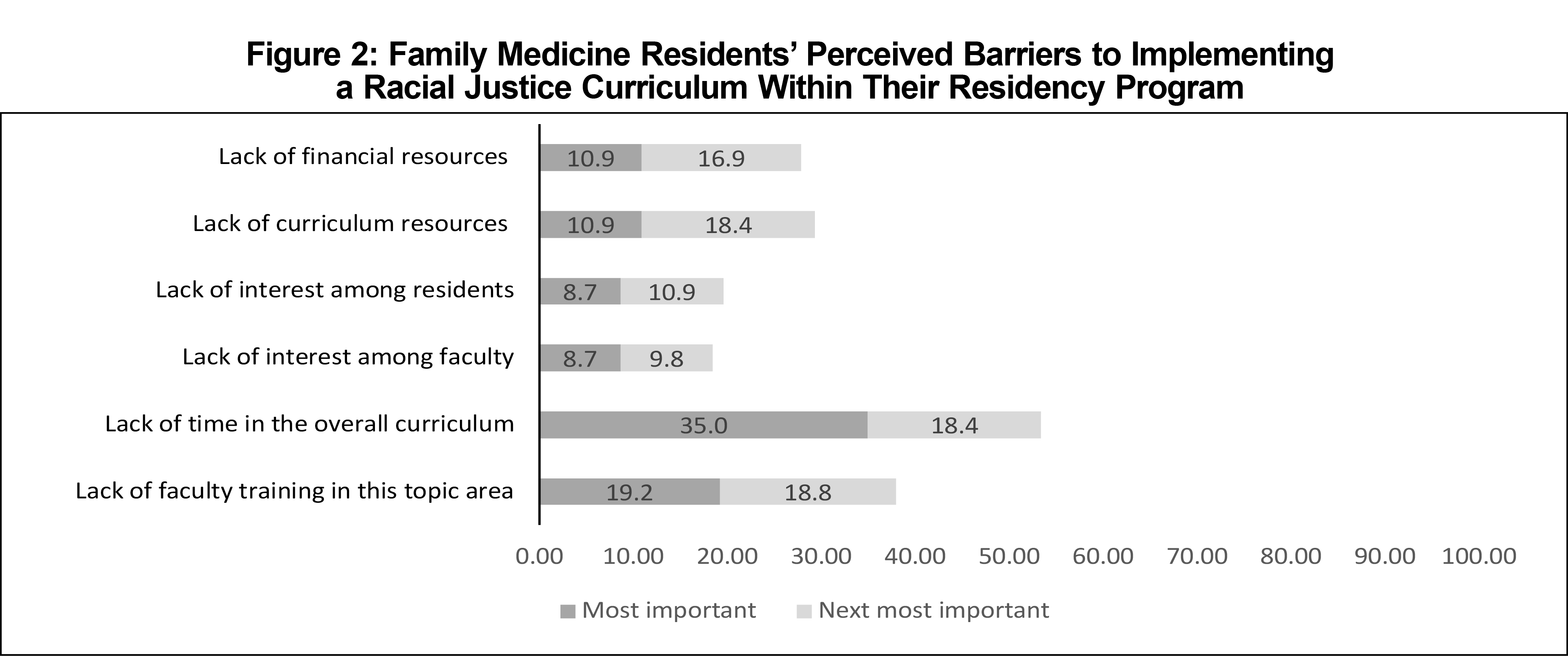

Residents self-identified various barriers to implementing RJT (Figure 2). The perceived barriers in order of frequency included lack of curricular time, lack of faculty training in this topic area, and lack of financial and curriculum resources. Table 2 shows that residents prioritized recruiting faculty of color, recruiting residents of color, and establishing community-based partnerships as components of RJT.

The findings of this CERA study of family medicine residents were consistent with our hypothesis that the majority of responding residents believed that it is important to address racism in medicine. Although less than one-fifth of responding residents believe they have consistent RJT; more than half reported sporadic trainings. Residents were more likely to have RJT if they agreed that their program prioritized addressing racism and if their program served a patient population where majority of patients identify as BIPOC.

The most significant perceived barriers by residents to implementation of RJT within FMRPs are lack of time and lack of faculty training. These findings are similar to the 2020 CERA survey of program directors, but more program directors ranked lack of faculty training and lack of curriculum resources as common barriers.10 Having faculty trained in the topic of racial justice is fundamental for a successful RJT.1,3,7

The call for more RJT in medical education has been ongoing for years. National institutions and organizations in medicine have recognized the importance of embarking in a cultural change with intention and urgency.4, 12-14 A program’s priorities are reflected in the core competencies outlined by the Accreditation for Graduate Medical Education. Specifically including racial justice curriculum in the updated Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Milestone as outlined by the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors and Health Equity Task Force will encourage all residencies to operationalize a racial justice lens.15,16

Our study has limitations, including an overall response rate of 5%, which is similar to prior published resident CERA studies. The results may not be generalizable to other residency specialties and nonresponders. Survey data were self-reported and thus subject to response bias and socially desirable answers. Furthermore, these answers are based on residents’ perceptions of their program and may not accurately reflect the program.

In summary, our study found that residents report a minority of FMRPs have been able to implement regularly occurring RJT. Our findings support the need for establishing an intentional RJT which necessitates protected curricular time and faculty training. Additional research should examine the content and impact of current racial justice curriculum and identify strategies to further implement such programs as well as the effectiveness to ultimately combat systemic racism.

Acknowledgments

Authors T.F.H., B.L., and A.Z. all contributed equally to the development of this project including the project proposal to CERA, manuscript writing, and editing.

Presentations: This Study was presented at 2022 STFM Annual Spring Conference as lecture-discussion.

References

- Acosta D, Ackerman-Barger K. Breaking the silence: time to talk about race and racism. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):285-288. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001416

- Ahmad NJ, Shi M. The need for anti-racism training in medical school curricula. Acad Med. 2017;92(8):1073. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001806

- Ona FF, Amutah-Onukagha NN, Asemamaw R, Schlaff AL. Struggles and tensions in antiracism education in medical school: lessons learned. Acad Med. 2020 Dec;95(12S Addressing Harmful Bias and Eliminating Discrimination in Health Professions Learning Environments):S163-S168. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003696.

- Sexton SM, Richardson CR, Schrager SB, et al. Systemic racism and health disparities: a statement from editors of family medicine journals. Fam Med. 2021;53(1):5-6. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.805215

- Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X

- Chin MH. Creating the business case for achieving health equity. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(7):792-796. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3604-7

- White-Davis T, Edgoose J, Brown Speights JS, et al. Addressing racism in medical education: an interactive training module. Fam Med. 2018;50(5):364-368. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.875510

- Hardeman RR, Medina EM, Kozhimannil KB. Structural racism and supporting Black lives - the role of health professionals. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2113-2115. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1609535

- Tsai J, Crawford-Roberts A. A call for critical race theory in medical education. Acad Med. 2017;92(8):1072-1073. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001810

- Wusu MH, Baldwin M, Semenya AM, Moreno G, Wilson SA. Racial justice curricula in family medicine residency programs: a CERA survey of program directors. Fam Med. 2022;54(2):114-122. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2022.189296

- Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW. Creating a centralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257-260. doi:10.1370/afm.2228

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Addressing and eliminating racism at the AAMC and beyond. Accessed August 18, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/addressing-and-eliminating-racism-aamc-and-beyond

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medcial Education. Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. Accessed August 14, 2021. https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Diversity-Equity-and-Inclusion

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Institutional Racism in the Health Care System. 2019. Accesed August 18, 2021. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/institutional-racism.html

- Kaufman A, Scott MA, Andazola J, Fitzsimmons-Pattison D, Parajón L. Social Accountability and Graduate Medical Education. Fam Med. 2021;53(7):632-637.

- Ravenna PA, Wheat S, El Rayess F, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion milestones: creation of a tool to evaluate graduate medical education programs. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14(2):166-170. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-21-00723.1

There are no comments for this article.