Introduction: Vaccine hesitancy remains a barrier to community immunity against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Health care workers are at risk both of infection and for nosocomial transmission, but have low rates of vaccine uptake due to hesitancy. This project sought to improve the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine uptake among environmental services (EVS) workers at a large academic regional medical center using a community-based participatory approach (CBPA).

Methods: The CBPA engaged environmental service workers from January 2021 to March 2021. Public health experts and environmental services department leaders developed a 1-hour training for peer lay health educators (N=29), referred to as agents of change (AOC). AOC were trained on COVID-19 infection, benefits of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, and techniques to address vaccine misinformation among their peers. Following the program, we conducted semistructured interviews with the AOC to document their experiences.

Results: Analysis of the semistructured interviews shows that 89.6% of participants (N=26) felt the training was informative; 79.3% of participants (N=23) reported using personal testimony while engaging in discussions about vaccination with their peers, and the majority of participants (N=26, 89.6%) discussed vaccination outside of the workplace in other community settings. During the 2-month time span of the program, mRNA COVID-19 vaccination rates among the EVS staff increased by 21% (N=126 to N=189).

Conclusion: Our CBPA program demonstrated an increase in mRNA COVID-19 vaccine uptake through using an AOC lay health educator model. As the need for COVID-19 vaccination continues, we must continue to investigate barriers and sources of hesitancy in order to address these through tailored interventions.

Vaccinations are one of the best public health tools to reduce infection and are key to ending the COVID-19 pandemic. In order to achieve herd immunity against SARS-CoV-2, at least 80% of the population needs to be vaccinated,1 a milestone that has proven difficult due to hesitancy. Despite being at increased risk of becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2,2–4 health care workers (HCW) including environmental service (EVS) workers, also have misconceptions about vaccines. When vaccines first became available, roughly one in three HCW (29%) said they “probably or definitely would not get vaccinated,” comparable with 27% of the general public that were hesitant.5,6

HCW are also important to the success of COVID-19 vaccination efforts, as they can serve as a communication network with the public about the risks of COVID-19, as well as the personal benefits of vaccination. Word of mouth can be effective in changing health behaviors.7 Peer-to-peer support through the use of lay health educators has been shown to improve health behaviors through providing social support while relaying information. EVS workers can serve as lay health educators, referred to in this program as agents of change (AOC), and are defined as health care workers carrying out functions related to health care delivery.8 AOC are individuals already familiar with the department culture who can spread awareness and information about the COVID-19 vaccine to their colleagues in order to promote vaccination.9–11 The AOC selected to disseminate information via word of mouth are considered influencers and are trusted community members, which gives them access to address vaccine hesitancy with their peers. Peer support community-based participatory approach (CBPA) programs have been implemented in the past to help mitigate health disparities through building on strengths of the community. They allow for creative solutions to ongoing problems within a community where public health professionals can join members of the community as equal partners.12 CBPA programs recognize the importance of involving the population as active participants as a means to facilitate social change.12–17

This peer-support CBPA program sought to explore attitudes toward SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among EVS workers at Upstate Medical University, a department previously identified by leadership as having low rates of vaccination uptake. EVS department leaders selected the employees as agents of change (N=29) based on their history of being well respected among their peers. A 1-hour training session was developed by public health experts where AOC received information on COVID-19 infection, the benefits of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, and addressing vaccine misinformation among peers. After the training and following 2 months of the program, semistructured interviews were conducted on Zoom with each AOC to document their experiences. Interview audio files were transcribed using Otter.ai software (Otter.ai, Inc, Los Altos, CA). We identified themes by searching for common responses in the deidentified interview text using Atlas.TI qualitative analysis software (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). We grouped common responses to questions to determine reoccurring themes. An interview guide with questions and keywords used during analysis is available on the STFM Resource Library.18

The SUNY Upstate Institutional Review Board determined this project (1785663-1) does not meet the definition of human subjects research. This project was developed in order to improve institutional efforts and increase vaccination uptake using a lay health education program planning model. The program plan in real-time included improvements such as a visual vaccine counter in the department, posting support for EVS workers to vaccinate, one-on-one support for vaccine enrollment, and targeted messaging on EVS equipment. Postprogram changes includes celebrations and food vouchers for high vaccine uptake, as well as one-on-one conversation with leadership for vaccine hesitant employees. The information and evaluation generated from this program was used to create internal system improvements to support EVS vaccination. The project was not generalizable; the program was specific to the system and EVS department of Upstate Medical University.

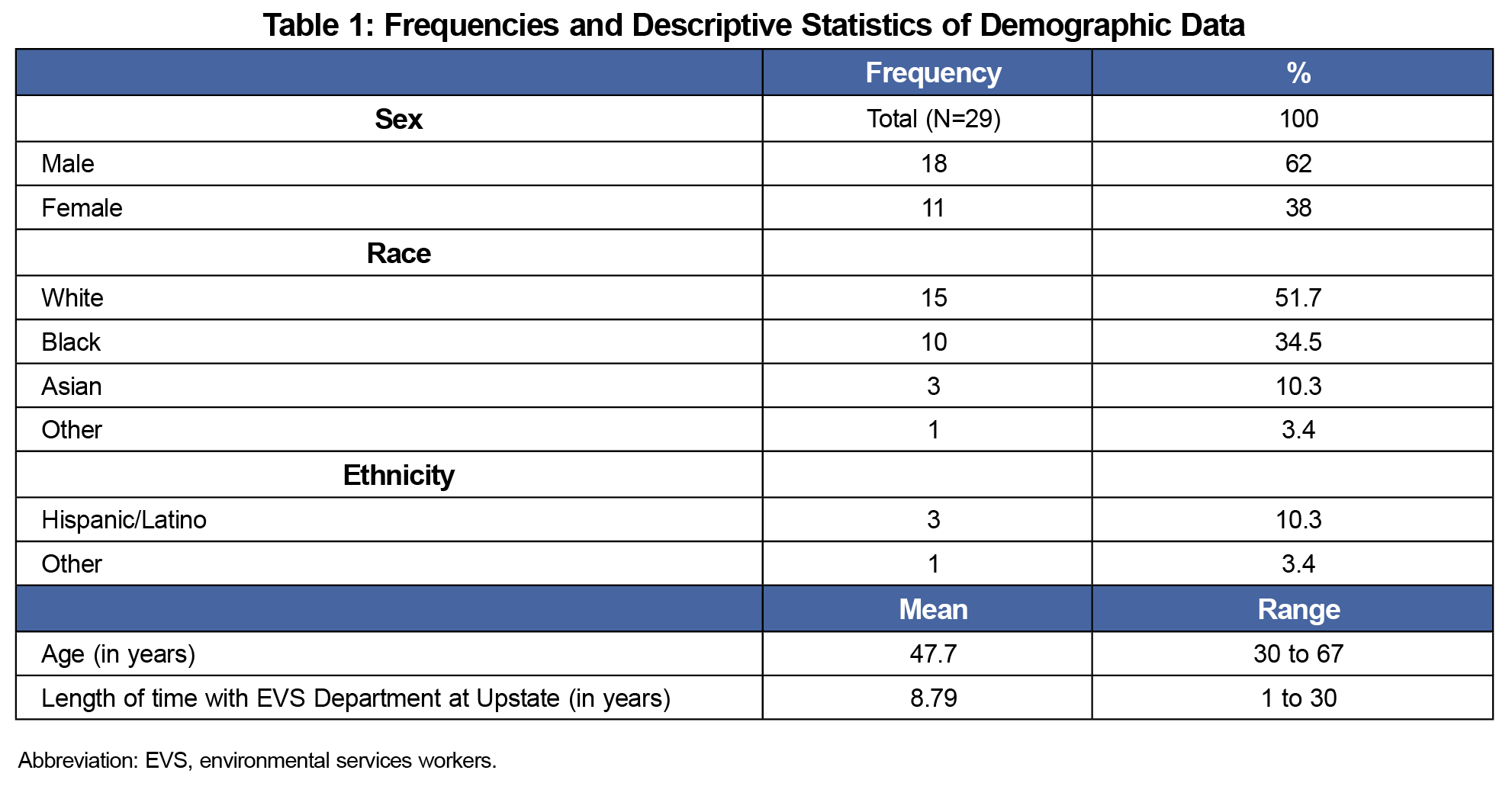

The mRNA COVID-19 vaccination coverage among the EVS department staff increased by 21% (N=126 to N=189) among the 310 total employees in the EVS department throughout the 2 months of the program. A total of 35 staff were initially approached and asked to be an AOC by leadership. Six EVS workers declined the opportunity for undisclosed reasons. The demographic characteristics for AOC including sex, age, race/ethnicity, and time spent working at the EVS department at Upstate Medical University are displayed in Table 1.

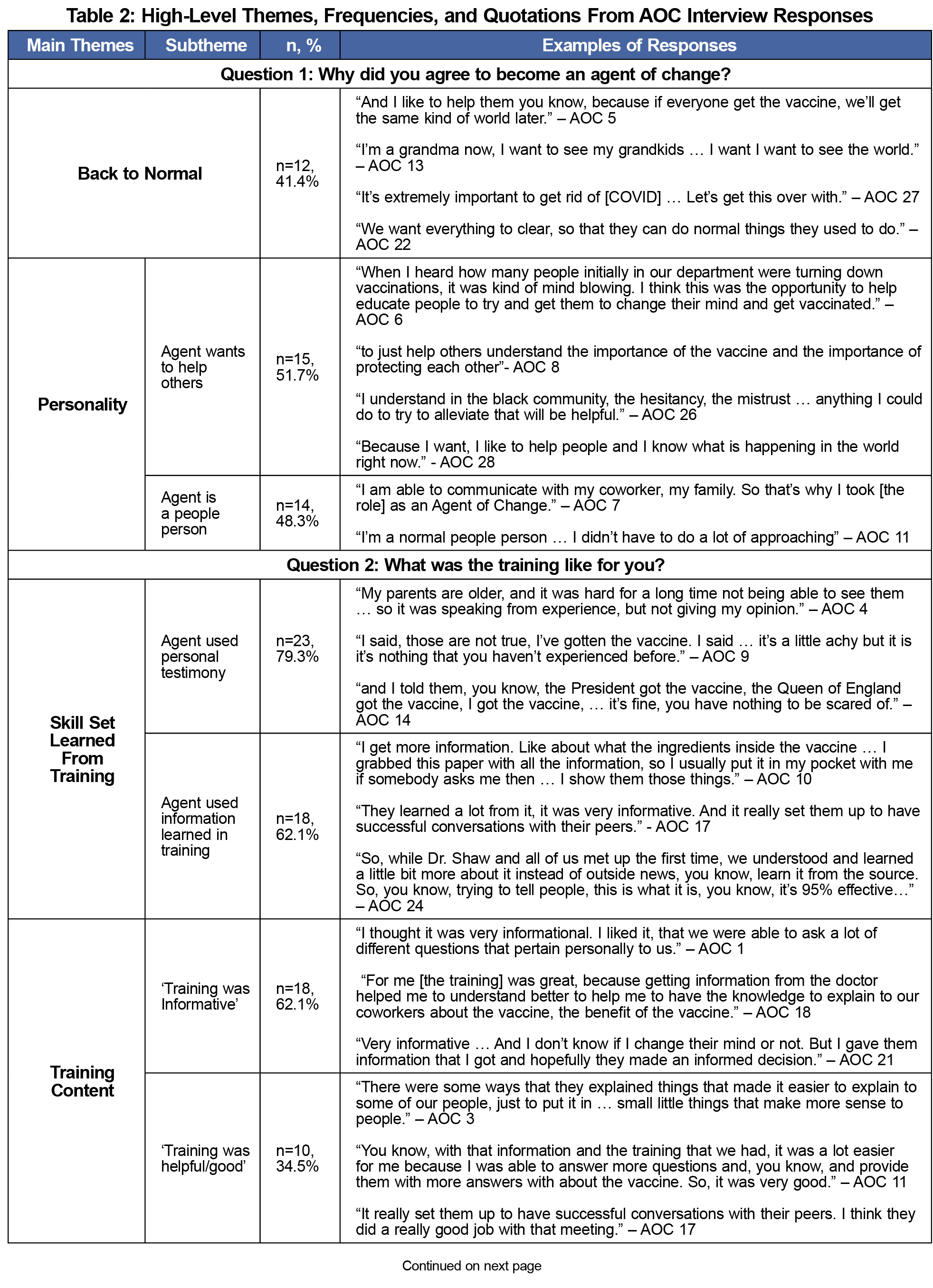

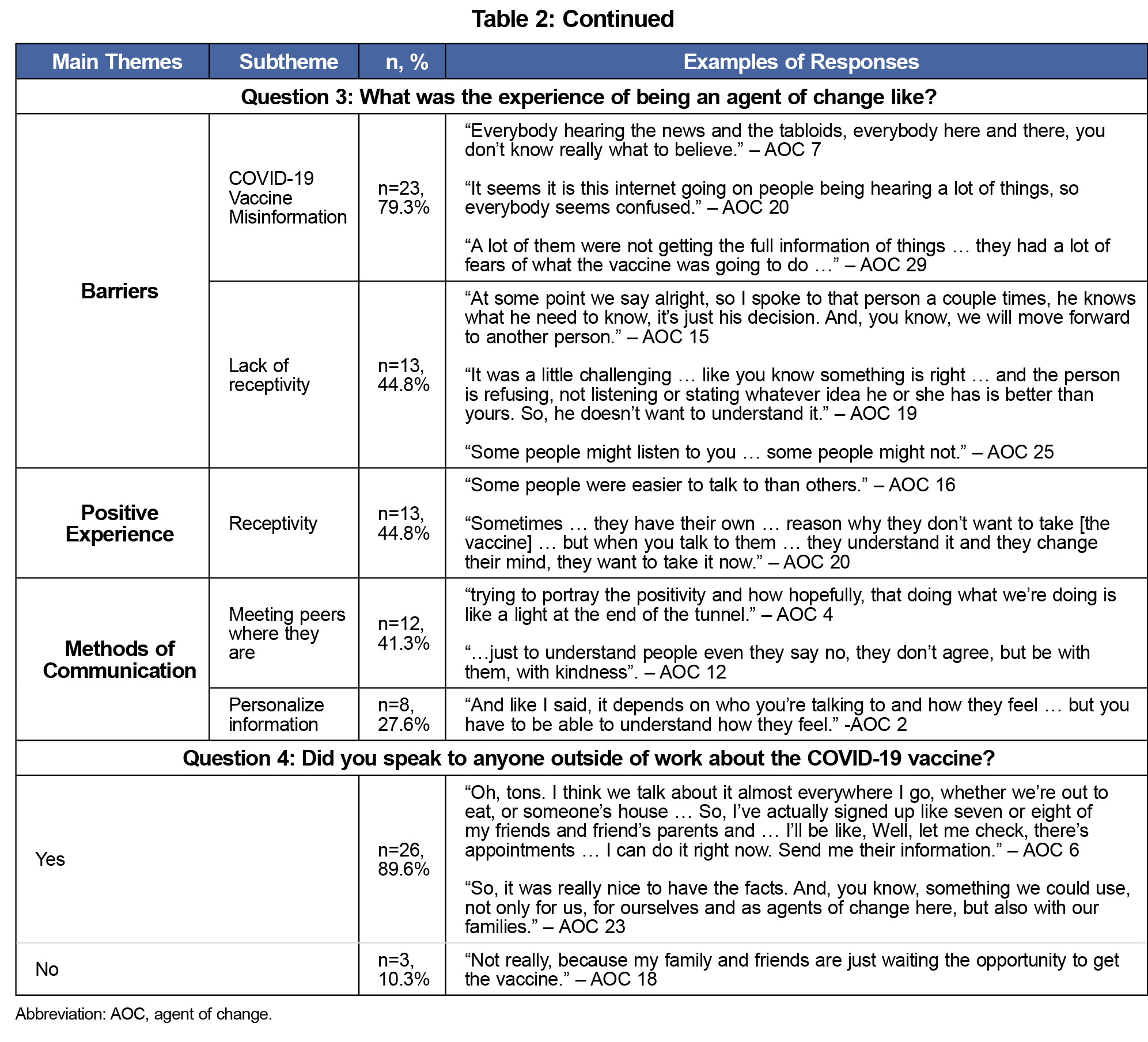

The AOC (N=29) participated in the semistructured interviews about their experiences. The high-level themes and subthemes in the interview responses, frequencies, percentages, as well as example responses are displayed in Table 2. Analysis determined that all of the AOC interviewed engaged in and lead discussions about vaccination with their peers after the training. Analysis also shows that 89.6% of participants (N=26) felt the training was informative; 79.3% of participants (N=23) used personal testimony while engaging in discussions about vaccination with their peers and the majority of participants (N=26, 89.6%) discussed vaccination outside of the workplace in other community settings. Approximately 80% of the AOC mentioned misinformation about the vaccine as a barrier and reason for hesitancy among their peers.

This CBPA program was composed of a training session that built on the lay health educators’ personality traits as leaders and provided them with a skill set that enabled them to speak to their peers about COVID-19 vaccination. By word of mouth, the AOC obtained information from their peer EVS staff members about their attitudes on the COVID-19 vaccine through informal conversations. The aims of the CBPA program include determining barriers to vaccination and overall reducing vaccine hesitancy in the EVS department through the use of a program planning and evaluation model and through collaboration with the EVS department as stakeholders. Additionally, the project sought to improve both access to COVID-19 vaccines and the rates of vaccine uptake, as well as lead action and inform future interventions for vaccine hesitancy.

Qualitative analysis of the interviews provided insight into why participants became an AOC. Most participants described wanting to see things “go back to normal” and get to the end of the pandemic. The AOC all reported positively on the 1-hour training experience and commonly mentioned the training was informative, helpful, and they were able to confidently speak with their peers about SARS-CoV-2 vaccination after the training. AOCs commented on barriers that included COVID-19 misinformation and lack of receptivity from their peers when they approached them with information. The AOCs also described the receptivity of COVID-19 vaccination information from their peers. Some described personalizing the vaccine information, and discussed facts specific to their coworkers’ concerns. The majority of AOC were able to hold conversations about COVID-19 vaccines outside of the workplace, showing that their roles as AOC did not end at the end of their workday.

An increase in vaccine uptake was demonstrated during the program; 63 EVS workers received vaccinations against SARS-CoV-2 from January 2021 to March 2021. Limitations include other vaccine initiatives taking place during the AOC project that may have also improved vaccination rates. This project would have benefited from documenting the EVS staff’s ultimate reason in getting vaccinated, whether discussion with AOC influenced their decisions, and the vaccination rates months following the program to assess long-term effects. Another limitation includes the AOC’s positive biases toward the project because of the scheduled semistructured interviews where they discussed their experiences. AOC also may have had positive bias towards the CBPA program based on their willingness to participate. Lastly, our study limitations include the timing of the project as rates of vaccination uptake were likely affected by vaccine availability in early 2021. In conclusion, this CBPA program can be an effective tool to influence health behaviors including the reduction of vaccine hesitancy in employees. CBPAs can improve health behaviors for vulnerable populations and can inform additional research and future interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors especially thank the SUNY Upstate Medical University Environmental Services Department Staff for their contributions to the program including Susan Murphy, Director and Brennan Laque, Manager; as well as Keith Adams, Joyce Appiah-Asare, Stephen B. Appiah-Asare, Al Brynien, Olivia Cheung, Bhim Chimoriya, Clark Cutri, Sherry Flansburg, Yobel Gonzalez Milian, Karen Hurtado-Hernandez, Bhola Khadka, John Kolh, Ziv Konsens, Lori Krause, Timothy A. Lawrence, Kelvin T. Little, Myron Martin, Younis Mosleh, Kenzo Mukendi, Magalie Norcilus, Loren Oatman, Yashira Romero, Anita Rouse, Jason Rupert, Moustapha Salawu, Steven Seeley, Stacey Todd, Jennifer Tyson, and Yetta Williams, their wonderful Agents of Change.

References

- Bartsch SM, O’Shea KJ, Ferguson MC, et al. Vaccine efficacy needed for a COVID-19 coronavirus vaccine to prevent or stop an epidemic as the sole intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(4):493-503. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.011

- Pearson ML, Bridges CB, Harper SA. Influenza Vaccination of Health-Care Personnel Recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. (ACIP). Accessed January 25, 2021. MMWR. 2006;February 24:55(RRO2);1-16. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5502a1.htm

- Influenza Vaccination Information for Health Care Workers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed November 24, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/healthcareworkers.htm

- The Importance of COVID-19 Vaccination for Healthcare Personnel. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations/hcp.html

- Artiga S, Rae M, Claxoton G, Garfiled R. Key Characteristics of Health Care Workers and Implications for COVID-19 Vaccination. Kaiser Family Foundation. Published January 21, 2021. Accessed February 21, 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/key-characteristics-of-health-care-workers-and-implications-for-covid-19-vaccination/

- Hamel L, Kirzinger A, Munana C, Brodie M. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor. December 2020. Kaiser Family Foundation. Published December 15, 2020. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/report/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-december-2020/

- Gürcü M, Korkmaz S. The importance of word of mouth communication on healthcare marketing and its influence on consumers’ intention to use healthcare. Int J Heal Manag Tour. Published online April 25, 2018:1-22. doi:10.31201/ijhmt.364494

- Lewin S, Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2017(3):CD004015. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004015.pub3

- Krukowski RA, Lensing S, Love S, et al. Training of lay health educators to implement an evidence-based behavioral weight loss intervention in rural senior centers. Gerontologist. 2013;53(1):162-171. doi:10.1093/geront/gns094

- Releford BJ, Frencher SK Jr, Yancey AK, Norris K. Cardiovascular disease control through barbershops: design of a nationwide outreach program. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(4):336-345. doi:10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30606-4

- Luque JS, Rivers BM, Kambon M, Brookins R, Green BL, Meade CD. Barbers against prostate cancer: a feasibility study for training barbers to deliver prostate cancer education in an urban African American community. J Cancer Educ. 2010;25(1):96-100. doi:10.1007/s13187-009-0021-1

- Holkup PA, Tripp-Reimer T, Salois EM, Weinert C. Community-based participatory research: an approach to intervention research with a Native American community. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2004;27(3):162-175. doi:10.1097/00012272-200407000-00002

- Hulen E, Hardy LJ, Teufel-Shone N, Sanderson PR, Schwartz AL, Begay RC. Community based participatory research (CBPR): A dynamic process of health care, provider perceptions and American Indian patients’ resilience. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2019;30(1):221-237. doi:10.1353/hpu.2019.0017

- Collins SE, Clifasefi SL, Stanton J, et al; The Leap Advisory Board. Community-based participatory research (CBPR): towards equitable involvement of community in psychology research. Am Psychol. 2018;73(7):884-898. doi:10.1037/amp0000167

- Martinez LSS, Zamore W, Finley A, Reisner E, Lowe L, Brugge D. CBPR partnerships and near‐roadway pollution: A promising strategy to influence the translation of research into practice. Environ - MDPI. 2020;7(6):1-13. doi:10.3390/environments7060044

- Coffman MJ, de Hernandez BU, Smith HA, et al. Using CBPR to decrease health disparities in a suburban Latino neighborhood. Hisp Health Care Int. 2017;15(3):121-129. doi:10.1177/1540415317727569

- Collins SE, Clifasefi SL, Stanton J, et al; The Leap Advisory Board. Community-based participatory research (CBPR): towards equitable involvement of community in psychology research. Am Psychol. 2018;73(7):884-898. doi:10.1037/amp0000167

- Ortiz C, Stewart T. Semi-Structured Interview Guide and Qualitative Analysis Keywords for Agents of Change Planning and Evaluation Project. STFM Resource Library. Uploaded June 1, 2022. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/semi-structured-interview-guide-and?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments

There are no comments for this article.