Introduction: Developing and implementing a wellness curriculum in a family medicine residency program is a complex process. We developed and implemented a new wellness curriculum in line with the national wellness conversation with a focus on the allocation of dedicated resources, the use of evidence-informed interventions, and the goal to be responsive to the feedback of both residents and residency leadership. Our research aim was to better understand the complexity of wellness curriculum implementation with a focus on identification of challenges to implementation.

Methods: We developed a wellness program with structured curricular elements initially focused on evidence-informed skill development that iterated after year 1 to include more process-oriented elements. For the years 2016-2019 we collected and analyzed qualitative, open-ended survey questions, anonymous resident curriculum feedback, and faculty observation forms to assess resident and faculty perspectives on the new curriculum.

Results: One hundred eighty-three survey invitations were sent with 122 total responses (66.7% response rate). Forty-eight of 56 residents responded to at least one survey. We analyzed responses along with the additional qualitative data that revealed several themes impacting the work of residency wellness curriculum implementation. These included how to manage curricular time, where the locus of control for the curricular content resides, and how residents and faculty differ in their definitions of wellness.

Conclusions: We believe programs will be well positioned if they further investigate the complex structures at play that influence residency wellness, including both systemic factors and individual and community level interventions, and design curriculum that is well-defined, includes essential elements, and is informed by resident participation.

The impact of burnout on the physician workforce and the quality, safety, and satisfaction of patient care is well documented1,2 and especially salient to family medicine, given the influence of increasing workforce demands and burnout reducing capacity.3 The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) inclusion of wellness in the common program requirements4 codifies trainee well-being as essential.

The literature to date has focused on skills such as mindfulness, self-compassion, and cognitive behavioral therapy5-9 that have been found successful, but there are also some noted cases of failures of these interventions to decrease burnout.10 Systemic drivers of burnout11 are also being explored but often are outside of programs’ control, leaving programs mostly focusing on the wellness curricula. The Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) Task Force on Resident Wellness developed a standard for programs12 but with little evidence published around the details of implementation. Recent literature suggests that having a champion, protected time, and a budget for wellness were associated with improved program director satisfaction in wellness curricula.13 However, there is little evidence on what residents find important.

The Family Medicine Residency at the University of Michigan Medical School developed an innovative curriculum in 2016 with three guiding principles: (1) allocate resources, (2) use evidence-informed interventions, and (3) respond to feedback. Our former curriculum emphasized momentary wellness (shared exercise, unstructured walks) and was shifted to structured elements centered on evidence-informed protective skills.5-7

Our research aim was a qualitative exploration of wellness program implementation from the perspective of residents and curricular faculty with an emphasis on barriers to successful implementation.

Curriculum Description

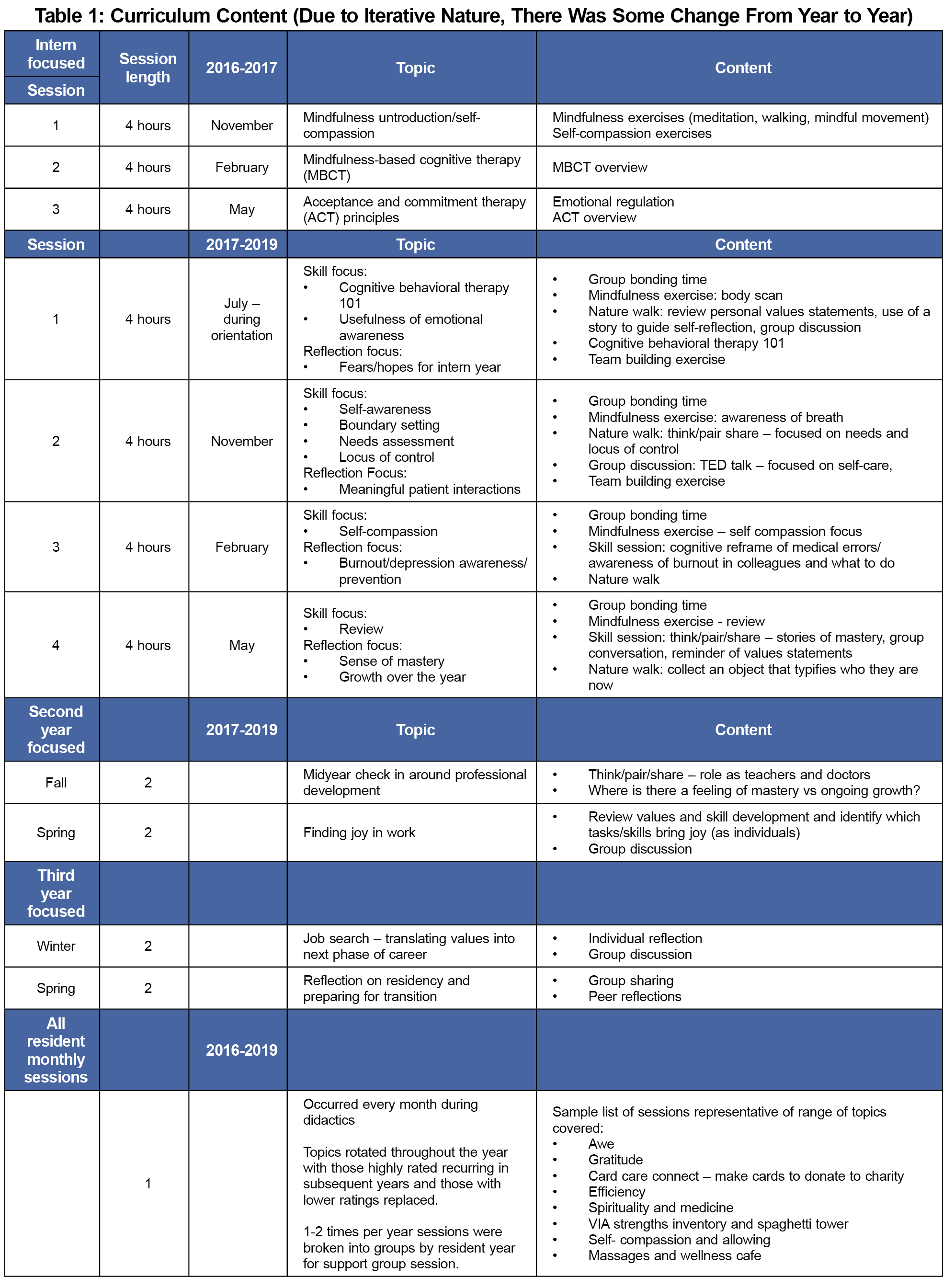

Our curriculum focused on the skills of mindfulness, self-compassion, cognitive behavioral therapy,5-7 and process-oriented relationship building time. Delivery occurred through three 4-hour sessions for interns starting in 2016-2017 increased to quarterly sessions for 2017-2019. Second- and third-year residents received 2-hour sessions starting in 2017 and continued through 2019. In addition, all residents received 1-hour monthly sessions (Table 1) beginning in 2016. All sessions were required.

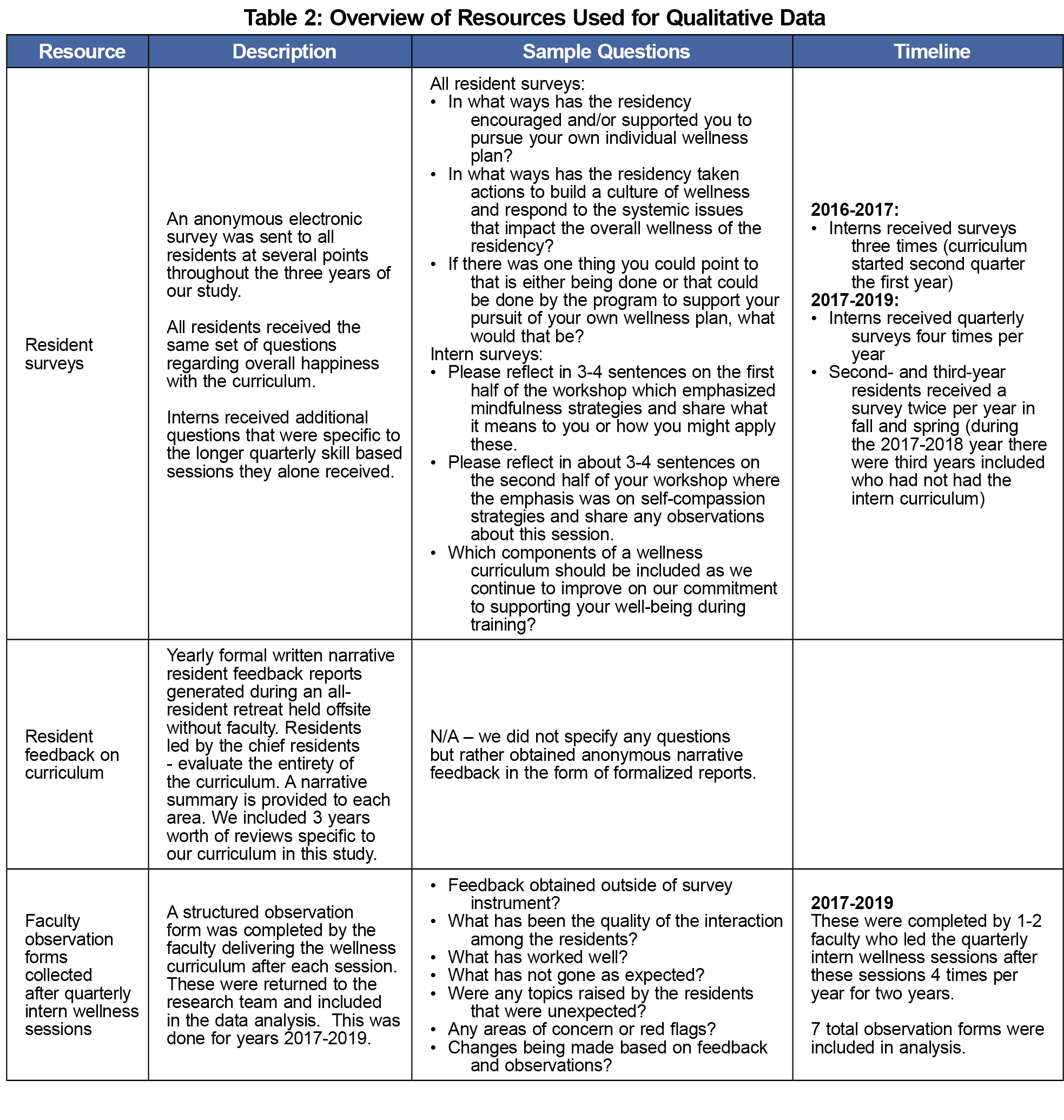

Using a qualitative descriptive design relying on purposive sampling and thematic analysis and interpretation of the data,14 we collected data for 3 years (2016-2019) through three qualitative sources. We collected voluntary anonymous surveys of all residents through software. The first-year surveys were sent three times to interns alone, followed in subsequent years by quarterly surveys to the interns and twice yearly to the second- and third-year residents. We sent 1-month reminders to nonresponders. Additional data sources included resident and faculty feedback as detailed in Table 2. This study was granted a Category One exemption from review for research regarding educational curricula by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan.

The open-ended survey responses were analyzed initially by three of four authors independently conducting qualitative thematic analysis, using immersion/crystallization, which is an iterative process of collecting, analyzing, reflecting and returning to the data to identify themes.15,16 Using this iterative immersion/crystallization, our four-member team returned to the data after the initial theme identification for further interpretation and through repeated group discussion identified thematic patterns described below.

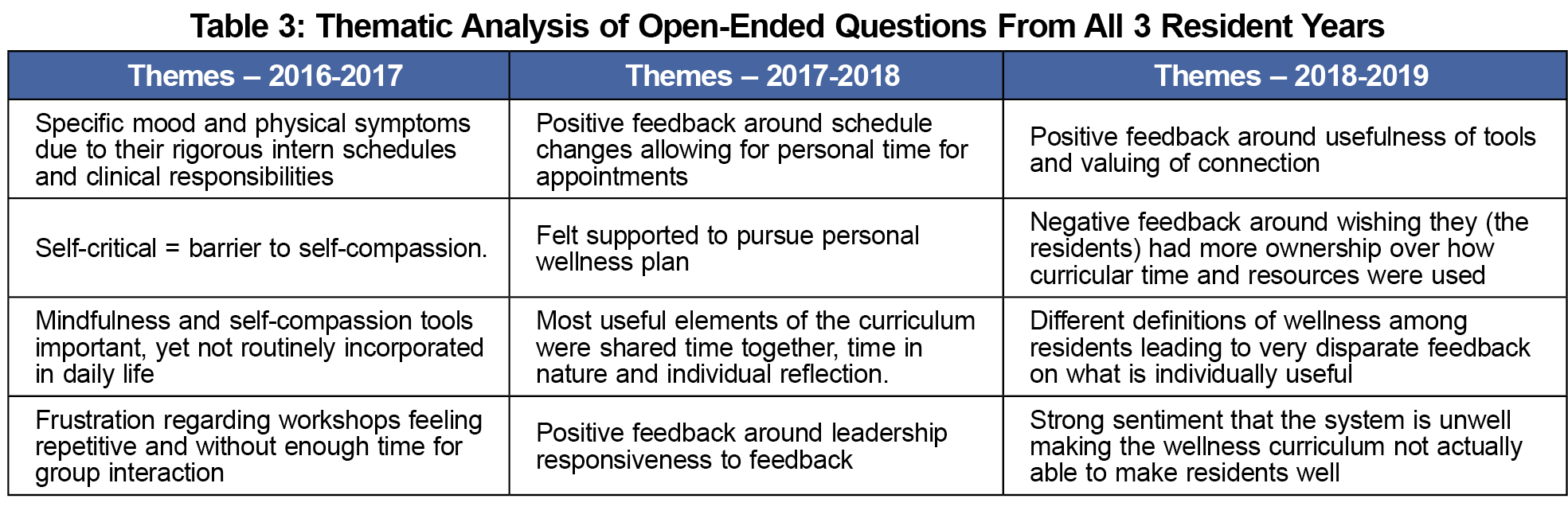

Of 183 survey invitations sent, 122 responded (66.7% response rate). Of the responses, 48 unique residents completed at least one survey out of 56 who participated in the curriculum. Our initial thematic analysis of the surveys resulted in themes both positive and negative that spoke to improvements in our curriculum but also the complexity of implementation (Table 3). Our deeper analysis of all the qualitative data identified three broad themes highlighting differences between resident and faculty perspectives.

The first theme involved use of time, specifically, the balance between structured (skill focused) and unstructured (processing/connecting) time and the balance between didactic and experiential elements. For example, one resident stated that “I appreciate them trying to teach techniques we can use all the time,” and a second resident reflected this theme in stating, “Maybe an over concentration on…the formal, a lot of talking at rather than practicing.” An additional component identified by faculty members was the need for safety within the unstructured time. One faculty member observed during the initial year that “While there was a growing openness and comfort with each other, there also appeared to be a level of guardedness in sharing struggles and challenges.” However, this contrasted with an observation by a different faculty member referring to a later year, with

“very intense personal discussion…several residents expressed feeling very burned out... The support from resident group was strong…at the end we asked them to write one word that summed up their experience of these sessions and every word was a variation on connection.”

The second theme extends the first, and is centered around the locus of control. Residents expressed desire for increased input as exemplified by this quote from a resident asking to “give us a few half days to orchestrate our own wellness activities.” Simultaneously, another resident noted a lack of enthusiasm for the planning when they expressed that “Brainstorming how to make the wellness curriculum better was useful, but not invigorating or refreshing…felt sort of like work.”

The third theme involved differing definitions of wellness with residents making statements that equated wellness with time to “do our work” or with time that “should be focused on social events.” This contrasted with the curriculum focus on evidence-informed skill-building activities.

These results explored a single residency’s design and delivery of a wellness curriculum highlighting challenges in implementation. There was tension around what elements should be given emphasis with faculty designing the curriculum focusing on skill development5-7 sessions and residents desiring less-structured relationship building17,18 and processing time.6 Faculty leaders noticed that smaller, more bonded groups could tolerate more vulnerability that resulted in greater benefit from the less-structured time but required attention to emotional safety and trust.

The second theme extends a known phenomenon that increased control tends to decrease stress and improve well-being.19 Evidence suggests greater efficacy in wellness curriculum with resident participation,19 therefore encouraging meaningful resident participation should be a goal. Residents’ perception that they had little control over curricular elements while at the same time admitting to less interest in engaging makes this a difficult balance to navigate.

The third theme pertains to differing definitions of wellness20,21 with our residents wanting time away from work to be included in the skill-focused wellness curriculum. Our qualitative data show resident preference for focus on systemic factors and work compression over skill development.11 Broadening the perspective of what is included is necessary, yet the larger systemic issues are better addressed outside of a curriculum by leadership. Our curriculum now begins with the development of a shared definition of wellness and agreement on common goals.

Major weaknesses of this study are its small size and scope as well as potential for bias. A path forward lies in ongoing research with larger pools of residents and the development of curricula that incorporate a majority of “essential elements,”12 achieve balance between relational time, skill building, and process-oriented sessions, and continued efforts to impact the larger systems that influence wellness.

Acknowledgments

Presentations:

A portion of this manuscript was presented as a poster session at American Conference on Physician Health, hosted by Stanford/American Medical Association, in San Francisco, California in 2017, entitled, “A Framework for Approaching Resident Wellness.”

References

- Shanafelt TD, Mungo M, Schmitgen J, et al. Longitudinal study evaluating the association between physician burnout and changes in professional work effort. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(4):422-431. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.02.001

- Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-1331. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713

- Rabatin J, Williams E, Baier Manwell L, Schwartz MD, Brown RL, Linzer M. Predictors and outcomes of burnout in primary care physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(1):41-43. doi:10.1177/2150131915607799

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/what-we-do/accreditation/common-program-requirements/

- Beckman HB, Wendland M, Mooney C, et al. The impact of a program in mindful communication on primary care physicians. Acad Med. 2012;87(6):815-819. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318253d3b2

- Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1284-1293. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1384

- Brennan J, McGrady A, Tripi J, et al. Effects of a resiliency program on burnout and resiliency in family medicine residents. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2019;54(4-5):327-335. doi:10.1177/0091217419860702

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-2281. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X

- Runyan C, Savageau JA, Potts S, Weinreb L. Impact of a family medicine resident wellness curriculum: a feasibility study. Med Educ Online. 2016;21(1):30648. doi:10.3402/meo.v21.30648

- Williamson K, Lank PM, Hartman N, et al; Emergency Medicine Education Research Alliance (EMERA). The implementation of a national multifaceted emergency medicine resident wellness curriculum is not associated with changes in burnout. AEM Educ Train. 2019;4(2):103-110. doi:10.1002/aet2.10391

- Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-146. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004

- Penwell-Waines L, Runyan C, Kolobova I, et al. Making sense of family medicine resident wellness curricula: a delphi study of content experts. Fam Med. 2019;51(8):670-676. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.899425

- Penwell-Waines L, Cronholm PF, Brennan J, et al. Getting it off the ground: key factors associated with implementation of wellness programs. Fam Med. 2020;52(3):182-188. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.317857

- Sandelowski M. What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in nursing & health. 2010. Feb;33(1):77-84. doi:10.1002/nur.20362

- Crabtree BFMW. Doing qualitative research.2nd ed. Sage; 1999.

- Borkan JM. Immersion-Crystallization: a valuable analytic tool for healthcare research. Fam Pract. 2022;39(4):785-789. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmab158

- Schwartz R, Haverfield MC, Brown-Johnson C, et al. transdisciplinary strategies for physician wellness: qualitative insights from diverse fields. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(7):1251-1257. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-04913-y

- Law M, Lam M, Wu D, Veinot P, Mylopoulos M. Changes in personal relationships during residency and their effects on resident wellness: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2017;92(11):1601-1606. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001711

- Lefebvre D, Dong KA, Dance E, et al. Resident physician wellness curriculum: a study of efficacy and satisfaction. Cureus. 2019;11(8):e5314. doi:10.7759/cureus.5314

- Brady KJS, Trockel MT, Khan CT, et al. What do we mean by physician wellness? a systematic review of its definition and measurement. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(1):94-108. doi:10.1007/s40596-017-0781-6

- Bohman B, Dyrbye L, Sinsky C, et al. Physician well-being: the reciprocity of practice efficiency, culture of wellness, and personal resilience. NEJM Catal. 2017.

There are no comments for this article.