The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) identifies the program coordinator (PC) as a liaison, administrator, manager, and member of the leadership team.1,2 It further acknowledges that PCs play a substantial role in resident support. 2-4 PCs contribute to personnel and program management and professional development initiatives3 while also providing informal social support to residents. 4 PCs must therefore develop and demonstrate competency with diversity, equity, inclusion and bias (DEI). We were unable to find previous literature describing PC learning needs, levels of interest, and self-reported skills and attitudes regarding DEI and bias initiatives in graduate medical education (GME). This study sought to describe the characteristics, knowledge, and attitudes of program coordinators attending a professional development workshop about DEI and bias.

RESEARCH BRIEF

Results of a Needs Assessment for a DEI Workshop for GME Program Coordinators

Kate Rowland, MD, MS | Lauren Anderson, PhD, MEd | Katherine M. Wright, PhD, MPH | Megham Twiss, MAT, MDiv | Jory Eaton, MBA, C-TAGME | Khalilah Gates, MD

PRiMER. 2024;8:39.

Published: 8/5/2024 | DOI: 10.22454/PRiMER.2024.209059

Introduction: Competency in diversity, equity, and inclusion skills is critical for graduate medical education program coordinators. Coordinators contribute to high-level personnel and program management while also providing informal social support to residents. However, little has been reported about program coordinator learning needs, interest, and self-reported skills and attitudes regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives in graduate medical education. This study sought to describe the characteristics, job tasks, attitudes, and learning needs of program coordinators attending a professional development session about diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Methods: Participants registered for a September 2022 program coordinator professional development workshop on diversity, equity, inclusion, and bias were invited to complete an electronic needs assessment prior to the workshop. Items were based on expert opinion and literature review. We performed descriptive and comparative analysis.

Results: The response rate was 54% (106/198); 90% (94/104) of respondents identified as female; 42% (44/104) identified as an underrepresented minority. Fifty-seven percent (63/104) received mandatory training on bias while 13% (14/104) were previously trained on bias at a conference specific to the role of a coordinator. Eighty-nine percent (86/104) of coordinators reported having contact with applicants during recruiting; 67% (63/104) offer informal resident evaluations. Most participants agreed it is the coordinator’s professional responsibility to confront colleagues who display signs of discrimination toward women (66%; 62/104) or based on cultural/ethnic identity (65%; 61/104).

Conclusions: Program coordinators report visible and impactful roles in the residency leadership and management team. Few coordinators have received diversity, equity, and inclusion training related to their complex work in graduate medical education. Future graduate medical education diversity, equity, inclusion, and bias competency programs should specifically include program coordinators.

Participants

The invited participants included all PCs (N=198) registered for a professional development workshop in September 2022 on DEI in GME for program coordinators. The workshop was held by the Chicago Area Medical Education Group (CAMEG), a local consortium of GME leaders. The workshop was open to all GME PCs in the consortium. A needs assessment was electronically sent 1 week prior to the session. Results were used to tailor the workshop. No identifiers were collected.

Tool

The needs assessment included attitude items about DEI, bias, privilege, social justice and allyship, previous training, current roles, and demographic questions. Perception and opinion items were based on literature review of previously-created tools and expert opinion.5,6 The 31-item survey was drafted by one member of the CAMEG research committee based on a literature review and expert opinion from the workshop presenter. It was revised iteratively by members of the research committee to arrive at the final set of questions. The Social Issues Advocacy Scale, a validated measure of participants’ DEI perceptions and opinions, was used with the permission of the original authors. Because other validated tools could not be found in the literature, the research committee wrote and revised their own to assess other areas of interest. The survey was tested by other members of the committee prior to distribution.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics including item means, percentages, and frequencies were calculated for all quantitative survey items. We used Χ2 analysis to assess the relationship between categorical variables. We performed all analyses using IBM SPSS Version 28 software for Windows (Armonk, NY; IBM Corp). This study deemed “not human subjects research” by institutional review boards at both Northwestern University and Rush University.

Response Rate and Demographics

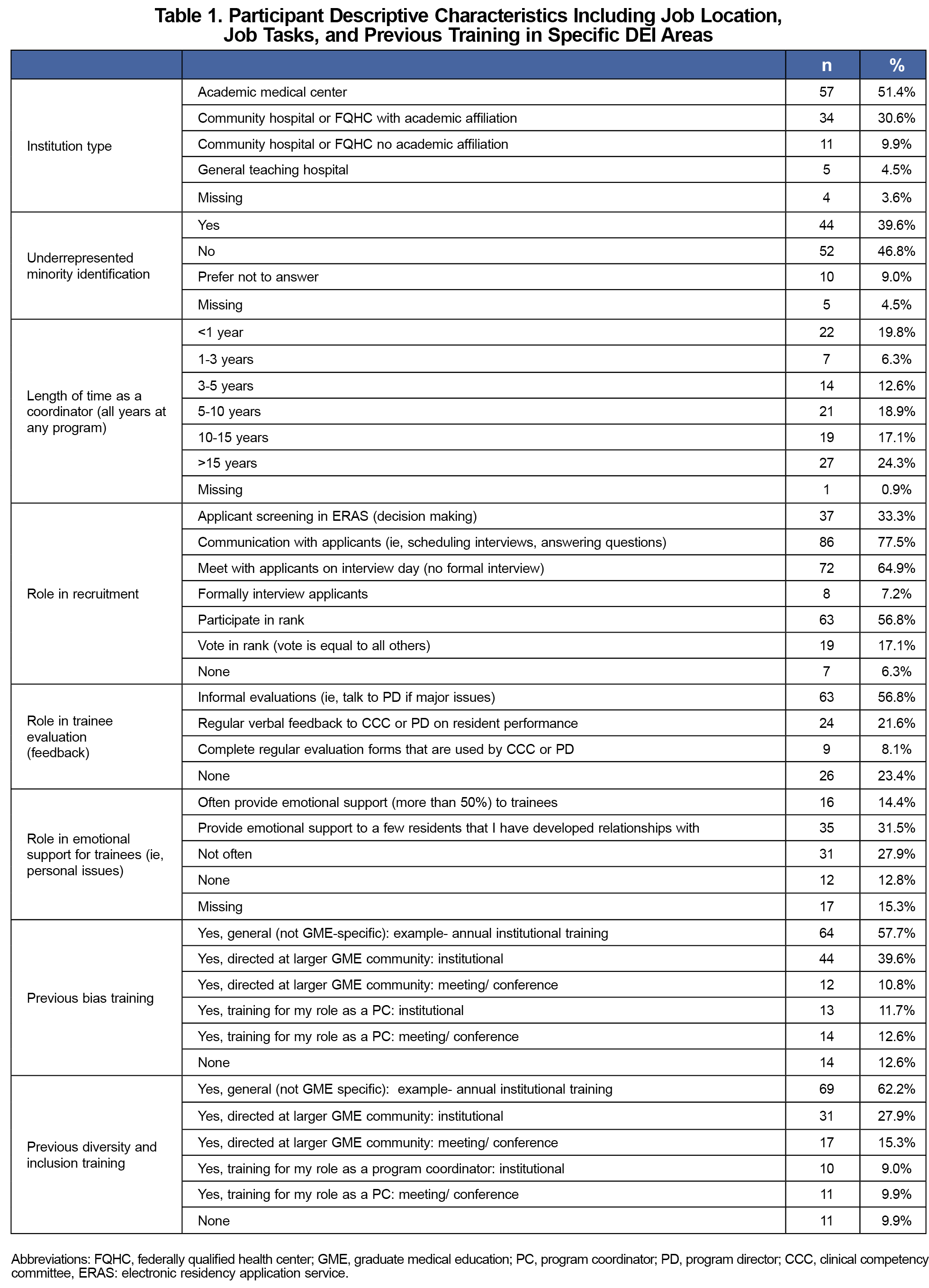

The response rate was 56.1% (111/198); 90.1% (100/111) of respondents identified as female; 41.5% (44/106) identified as a member of an underrepresented group. Tenure as a coordinator varied; 24.6% (27/110) had more than 15 years of experience, while 20.0% had been on the job less than 1 year. Institution type varied (53.3% academic centers; 57/107).

Previous training. Nearly fifty-eight percent (64/111) received mandatory training on bias only while 12.6% (14/111) were previously trained on bias at a conference specific to the role of a PC (Table 1); 50.9% (29/57) of PCs employed at academic institutions received institutional GME specific training compared to 29.2% of their peers (14/48) at community-based institutions (Χ2=5.1, P=.02).

Job Description

Recruiting. Nearly 78% (86/111) of PCs reported having contact with applicants during recruiting; 33.3% (37/111) report screening applicants in ERAS. Nearly 57% (63/111) reported participating in the rank process; 17.1% (19/111) reported having a voting role in ranking applicants.

Evaluation. Nearly 57% (63/111) of respondents offer informal evaluations; 23.4% (26/111) reported never evaluating trainees. Nearly 22% (24/111) give verbal feedback to the clinical competency committee (CCC) or program director (PD), and 8.1% (9/111) complete evaluation forms used by the program.

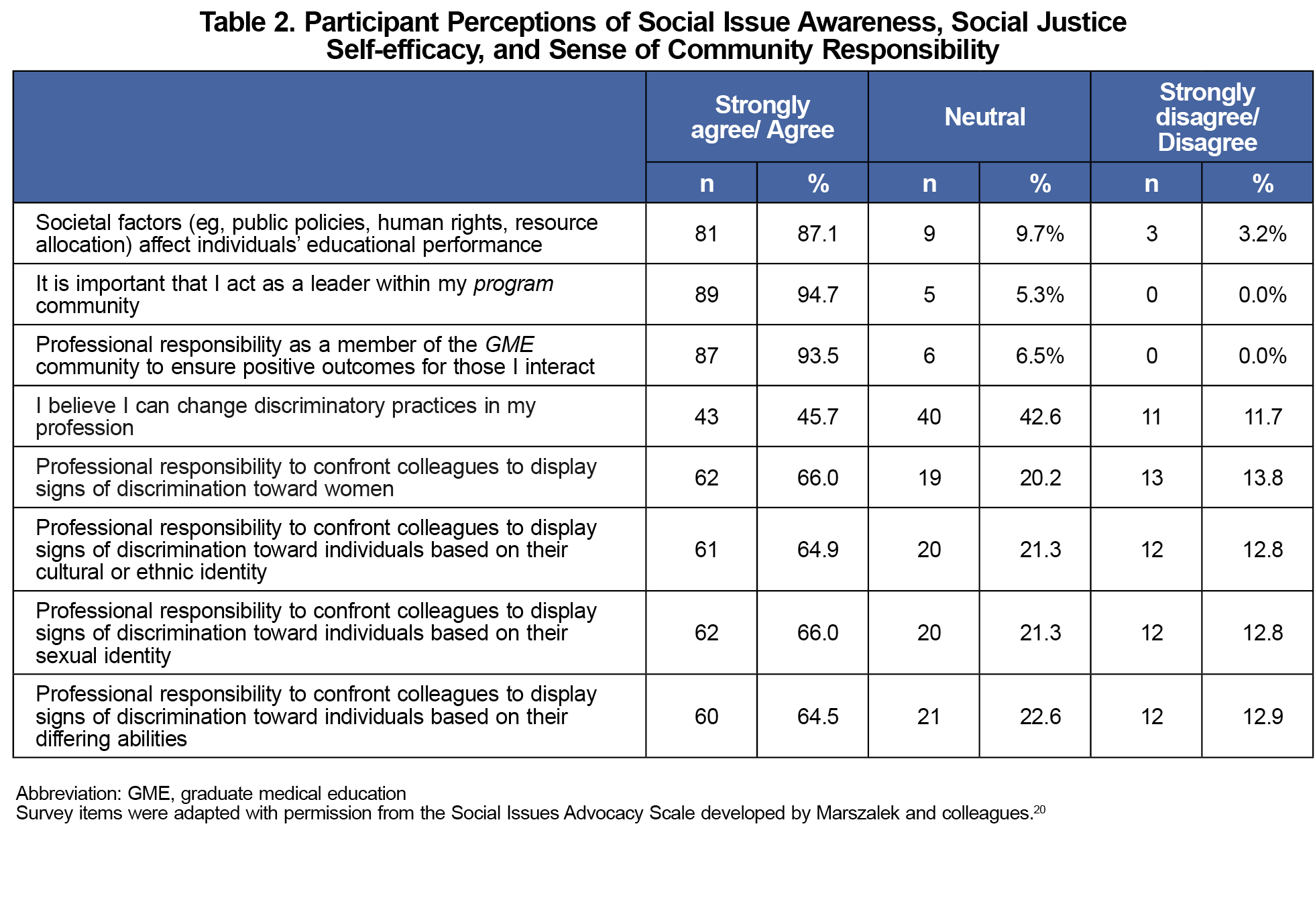

DEI attitudes. Eighty-seven percent (81/93) of participants agreed/strongly agreed that societal forces affect individual performance. Most agreed/strongly agreed it is the PC’s professional responsibility to confront colleagues who display signs of discrimination toward women (66.0%; 62/94) or based on cultural/ethnic identity (64.9%; 6/94). Similar proportions reported feeling a professional responsibility to confront colleagues who display signs of discrimination toward individuals based on sexual identity (66%; 62/94) or differing abilities (64.5%; 60/93; Table 2).

Approximately 16.2% (18/93) of PCs reported previous professional development on DEI in the context of the PC role. That is, although more than half (62.2%; 69/111) reported having received some kind of DEI training, most of that training was not directly connected to the complex work of a GME PC. PCs require training tailored to their roles, with attention to the need for DEI awareness and competency in a range of areas, from individual resident support to human resources-level management to leadership. This job-specific competency would not likely be achieved in general staff training on DEI, which may serve more to provide information than to connect that information to specific action. Coordinators working at academic centers were more likely to report previous training than those working at nonacademic centers, such as community-affiliated hospitals or federally qualified health center programs.

Our study also found PCs have a substantial, impactful role in areas where knowledge, skill, and competency in DEI and bias are essential. PCs report high levels of involvement in residency recruitment, with nearly 93.7% (104/111) of PCs indicating at least some role in new resident recruiting. Approximately one in five PCs give feedback to the CCC and almost 76.6% (85/111) have some role in resident evaluation. Other studies confirm the result that PCs frequently have roles in recruiting, assessment, and resident development.7,8 Professional development that supports self-assessment and antidiscrimination/bias training is therefore imperative to prevent the worsening of existing inequity in areas such as evaluation and promotion.9-13 Training programs and metrics to teach and assess DEI competencies are increasingly common for faculty,14,15 but opportunities for coordinators appear to be limited, despite their unique roles in GME administration.

Previous literature suggests administrative staff, including PCs, most frequently evaluate nonclinical aspects of resident development, such as professionalism competencies. 8 Without well-developed DEI skills, knowledge and awareness, PCs could contribute to the continuation of historical biases, particularly around professionalism.16 With increasing training in these areas, PCs can be leaders in efforts to promote equity and an environment of belonging for marginalized groups in medical education.

Approximately 54.3% (51/94) of respondents in this study stated they provide emotional support for trainees, consistent with previous studies that show PCs report providing direct, personal support to residents. 17 One study conducted in Japan found that PCs provided support to isolated residents, and further found that PCs contributed to creating a safe learning environment.18 Literature suggests that underrepresented in medicine (URiM) residents are more likely to experience isolation and less likely to have access to a supportive social community.19 Future work may focus on strengthening the role of PCs as important allies for URiM residents and as leaders in GME DEI.

This study demonstrates PCs report inconsistent levels of empowerment to change discriminatory behaviors and patterns in the workplace. About 64%-66% of respondents agreed they had a professional responsibility to do so, but fewer than half (45.7%, 43/94) agreed they felt empowered to make changes. Approximately 13% of respondents reported they did not feel a professional responsibility to confront colleagues who displayed signs of discrimination toward marginalized groups. This may reflect a legacy of coordinators in support rather than leadership roles, contrary to current expectations from the ACGME and most institutions. This may also reflect a need for further training to provide coaching, scripting, and empowerment. These results support the need for continued development specific to the role of the program coordinator. Coordinators at programs outside of academic medical centers reported lower rates of previous training compared to those at academic medical centers. Local, regional, or national consortia may be effective ways of providing coordinator support and professional development.

Limitations

This was a self-report needs assessment survey with a response rate of 56.1%, and we do not have data on nonresponders. As a self-report survey, the data are subject to biases including recall and social desirability bias. Participants were voluntarily attending a DEI and bias workshop to improve their knowledge and skills. Participants who choose to attend a DEI workshop may not be representative of all PCs.

In conclusion, we observe that PCs report visible and impactful roles in residency leadership and management and few coordinators have received DEI training related to their complex work in residency education.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Deborah Edberg, MD, Lisa Sanchez-Johnsen, PhD, and Mackenzie Krueger, MNM, C-TAGME, for their assistance with the development of this project.

Presentation: This research was presented at the 2023 ACGME annual meeting in Nashville, TN, in February, 2023.

References

- Common program requirements (residency). Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. 2022. Accessed June 26, 2024. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency_2022v2.pdf

- Nawotniak RH. Is your residency program coordinator successful? Curr Surg. 2006;63(2):143-144. doi:10.1016/j.cursur.2005.12.002

- Stuckelman J, Zavatchen SE, Jones SA. The evolving role of the program coordinator: five essential skills for the coordinator toolbox. Acad Radiol. 2017;24(6):725-729. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2016.12.021

- McCann WJ, Knudson M, Andrews M, Locke M, Davis SW. Hidden in plain sight: residency coordinators’ social support of residents in family medicine residency programs. Fam Med. 2011;43(8):551-555.

- Williams DR, Yan Yu, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of health psychology.J Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):335-351. doi:10.1177/135910539700200305

- Torres-Harding SR, Siers B, Olson BD. Development and psychometric evaluation of the social justice scale (SJS). Am J Community Psychol. 2012;50(1-2):77-88. doi:10.1007/s10464-011-9478-2

- Ronna B, Guan J, Karsy M, Service J, Ekins A, Jensen R. A survey of neurosurgery residency program coordinators: their roles, responsibilities, and perceived value. Cureus. 2019;11(4):e4457. doi:10.7759/cureus.4457

- Nickel BL, Roof J, Dolejs S, Choi JN, Torbeck L. Identifying managerial roles of general surgery coordinators: making the case for utilization of a standardized job description framework. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(6):e38-e46. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.07.003

- Brewer A, Osborne M, Mueller AS, O’Connor DM, Dayal A, Arora VM. Who gets the benefit of the doubt? performance evaluations, medical errors, and the production of gender inequality in emergency medical education. Am Sociol Rev. 2020;85(2):247-270. doi:10.1177/0003122420907066

- Klein R, Julian KA, Snyder ED, et al; From the Gender Equity in Medicine (GEM) workgroup. Gender bias in resident assessment in graduate medical education: review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(5):712-719. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-04884-0

- Ross DA, Boatright D, Nunez-Smith M, Jordan A, Chekroud A, Moore EZ. Differences in words used to describe racial and gender groups in Medical Student Performance Evaluations. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0181659. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181659

- Dill-Macky A, Hsu CH, Neumayer LA, Nfonsam VN, Turner AP. The role of implicit bias in surgical resident evaluations. Journal of surgical education. J Surg Educ. 2022;79(3):761-768. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.12.003

- Nguemeni Tiako MJ, Ray V, South EC. Medical schools as racialized organizations: how race-neutral structures sustain racial inequality in medical education—a narrative review. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(9):2259-2266. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07500-w

- Ravenna PA, Wheat S, El Rayess F, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion milestones: creation of a tool to evaluate graduate medical education programs. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14(2):166-170. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-21-00723.1

- Buery-Joyner S, Baecher-Lind L, Clare CA, et al. Educational guidelines for diversity and inclusion: addressing racism and eliminating biases in medical education. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;228(2)133-139. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.09.014

- Cerdeña JP, Asabor EN, Rendell S, Okolo T, Lett E. Resculpting professionalism for equity and accountability. Ann Fam Med. 2022;20(6):573-577. doi:10.1370/afm.2892

- McCann WJ, Knudson M, Andrews M, Locke M, Davis SW. Hidden in plain sight: residency coordinators’ social support of residents in family medicine residency programs. Fam Med. 2011;43(8):551-555.

- Aono M, Obara H, Kawakami C, et al. Do programme coordinators contribute to the professional development of residents? an exploratory study. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):381. doi:10.1186/s12909-022-03447-y

- Usoro A, Hirpa M, Daniel M, et al. Promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion: building community for underrepresented in medicine graduate medical education trainees. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(1):33-36. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-20-00925.1

- Marszalek JM, Barber C, Nilsson J. Development of the Social Issues Advocacy Scale-2 (SIAS-2). Social Justice Research. 2017; 30(2), 117–144. doi:10.1007/s11211-017-0284-3

Lead Author

Kate Rowland, MD, MS

Affiliations: Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, Rush University, Chicago, IL

Co-Authors

Lauren Anderson, PhD, MEd - Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, Rush University, Chicago, IL

Katherine M. Wright, PhD, MPH - Department of Family and Community Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL

Megham Twiss, MAT, MDiv - University of Chicago Hospitals, Chicago, IL

Jory Eaton, MBA, C-TAGME - Loyola Medicine, Chicago, IL

Khalilah Gates, MD - Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL

Corresponding Author

Kate Rowland, MD, MS

Correspondence: Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, 1700 W. Van Buren, Chicago IL 60612, 312-942-9442

Email: Kathleen_rowland@rush.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.