Introduction: Interest in training opportunities and ethical engagement in global health among medical trainees continues to increase. Preparation activities and formal curriculum for trainees traveling for international rotations vary widely across programs, and alignment with ethical best practice guidelines among US family medicine (FM) residency programs is unknown.

Methods: We surveyed FM residency programs about their global health (GH) curricula, with focus on practice alignment with ethical guiding principles for pretravel training in GH programs. We analyzed the responses by type of residency program and availability of faculty lead with expertise in GH.

Results: Fifty programs were included in analysis of GH curriculum specifics. Programs with expert leads were significantly more likely to have a formal GH curriculum and/or pretravel training, to offer formal and informal faculty mentorship on cultural expectations and global health ethics, and to include scope of practice (P=.001) and pretravel safety training with a standard institutional process (P=.011). Program type was not significantly correlated with global health curriculum specifics, except for availability of journal club. Small sample sizes limited our analysis of residency type.

Conclusion: Programs with an expert GH faculty lead were more likely to have formal GH curriculum or pretravel training with inclusion of elements recommended by the WEIGHT ethical best practices for GH training. Residency programs should consider designating lead faculty to formalize GH curriculum and mentorship in alignment with Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competency requirements and with WEIGHT ethical best practices.

Global health (GH) focuses on achieving improved access, outcomes, and health equity across diverse populations and regions.1,2 Increasingly apparent after the COVID-19 pandemic, there are global disparities in health access and outcomes for preventive and individual-level clinical care.3–6 The incoming generation of physicians is simultaneously requesting accountability to address these gaps while seeking personal global health experience to better understand the context.

The Working Group on Ethics Guidelines for Global Health Training (WEIGHT) consensus guidelines were published in 2010 and outlined the need for structured programs with adequate preparation, mentorship, and supervision for trainees. Their emphasis on long-term bidirectional partnerships with mutual benefit is essential to ensuring quality training in GH that protects trainees and host communities.7–11 There is also a push to close the gap in available published perspective from international partners who host GH experiences for medical trainees.12–17

Almost 75% of family medicine residencies now offer international or domestic training experiences in GH compared to 43% in 1996.18,19 The goals of these training experiences vary, as do the preparation activities for trainees traveling for international rotations.19–24 There are no current data on the specific components of GH training offered at these programs.

We conducted this survey for two reasons. First, we sought to describe the current components of GH training opportunities offered by US family medicine residency programs. Secondly, we wanted to assess programs’ alignment with the WEIGHT guidelines, specifically formal pretravel training including norms of professionalism, cultural expectations, personal safety, and the guiding principles of mitigating harm and fostering reciprocity and sustainability. Our analyses also focused on testing where presence of a designated global health expert faculty lead and residency type were associated with increased frequency of pretravel trainings.

We developed a survey instrument within REDCap software (institutional grant DHHS/NIH/NCRR #UL1TR001449) that assessed areas of opportunity consistent with the WEIGHT recommendations for institutions engaging in sending trainees for learning experiences abroad. In addition to descriptive demographics of responding programs, the survey questions focused on the WEIGHT guidelines for specific, formal, pretravel training material in GH curriculum for trainees. An invitation email included the consent language and a link to the REDCap survey.25 This same language was also on the landing page of the REDCap survey for participants accessing it by QR code and social media announcements. The survey instrument did not collect identifiers and is included in Appendix 1.26 The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of New Mexico Human Research Protection Office Institutional Review Board.

Between April 2022 and May 2023, we shared the survey with residency program directors and faculty from US-based family medicine training programs via email announcements to the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) Global Health Educators Collaborative (GHEC) listserv, the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) Global Health Interest Group (GHIG) listserv, and adjacent social media accounts. The QR code for the survey was also distributed through global health related sessions at the 2022 AAFP Family Medicine Experience (FMX) and 2023 STFM Annual Spring Conferences. The anonymous surveys collected during this period could have resulted in multiple responses from individual programs, and individual program directors and faculty could have responded more than once during the study period. To identify potential program duplicates we used responses for program state, number of residents, residency type, program age, main focus of global health rotations, presence of an expert faculty lead and required pretravel training on norms of professionalism. One record had matches across these variables, and we excluded the one record with a later survey date.

Survey questions were almost entirely multiple-choice items or checkboxes in which all that apply were selectable. We used frequencies and percentages to summarize items. Total number of residents was summarized by the mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum and median. Associations between categorical variables were made using χ2 tests and Fisher’s exact tests when sample sizes were limiting. Primary hypotheses tested were whether (a) presence of perceived faculty GH experts and (b) program type were associated with pretravel trainings. We compared number of residents and number of training types offered by subgroup using nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum tests and Kruskal-Wallis tests.

We considered tests statistically significant at P<.05. We used SAS v9.4 software (SAS Inc, Cary, NC) for data management and statistical analyses. Respondent representation across geographic location and program type is provided for transparency on potential bias and confounding factors based on convenience sampling.

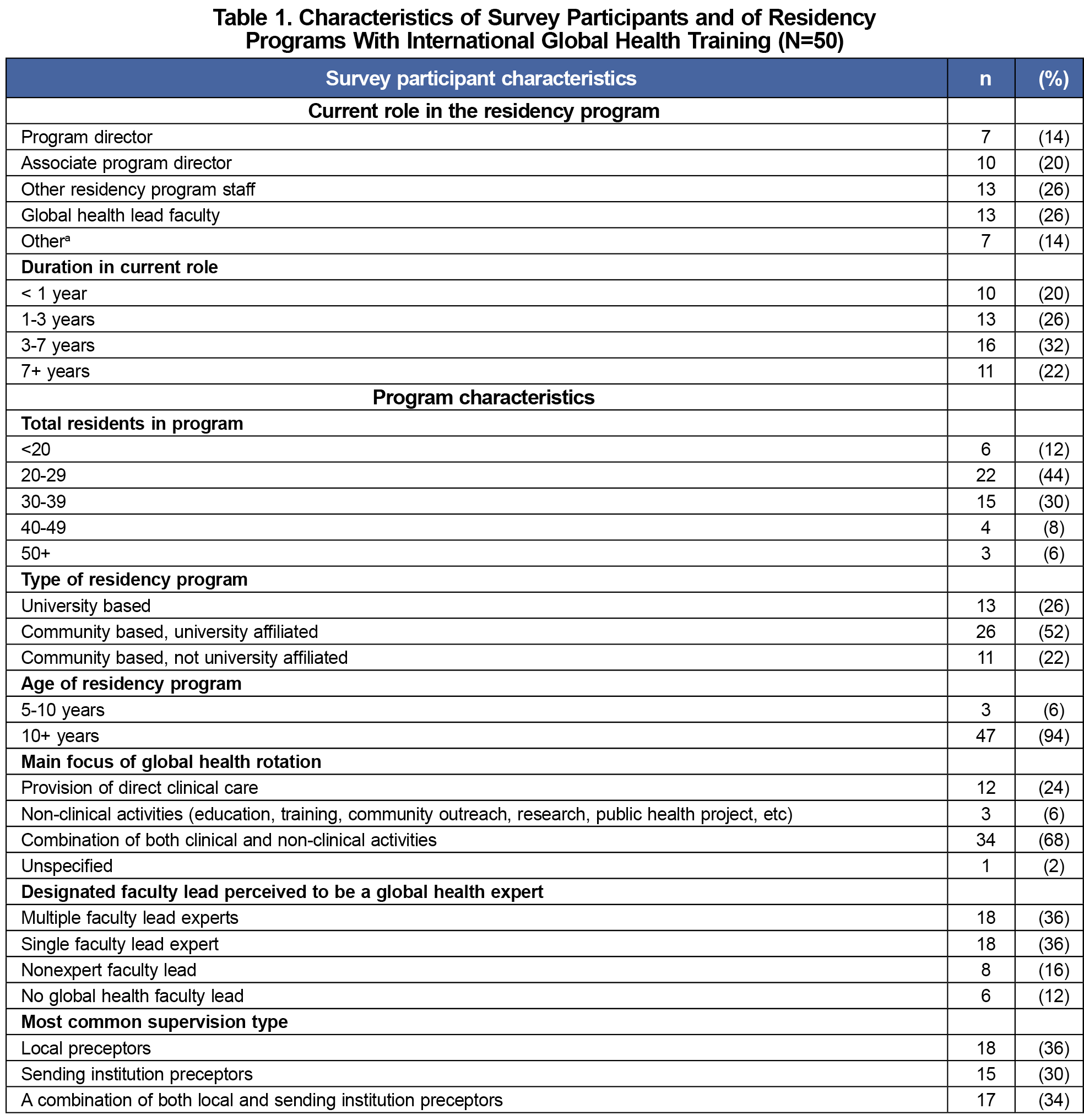

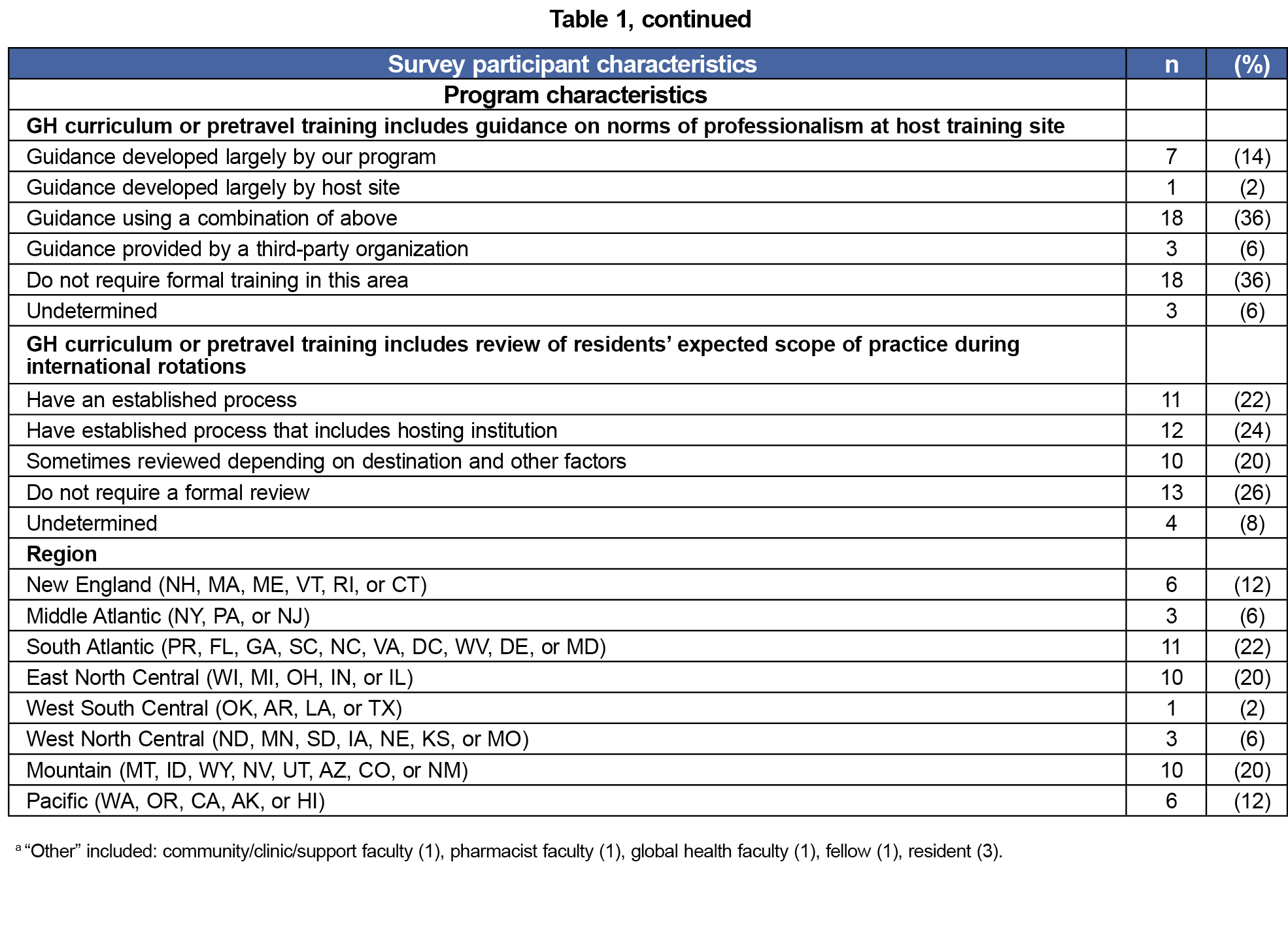

A total of 71 surveys were returned. Before conducting analyses, we excluded one medical student, one potential duplicate program record, and 19 that did not have international GH training opportunities. Characteristics of the remaining 50 programs are shown in Table 1. Thirty-four percent of surveys were returned by program directors or associate directors and 26% came from GH lead faculty. The average number of residents was 30.1 (SD=10.7, range=6-64, median=28) with 52% of programs being community-based with a university affiliation. Most programs (94%) had existed for at least 10 years and had a focus on a combination of clinical and nonclinical activities (68%). Twenty-eight percent did not have an expert GH faculty lead. Thirty-six percent of preceptors were local, 30% sending institutions, and 34% a combination of the two. Thirty-six percent of programs did not have formal training in professionalism norms at hosting sites, and 26% did not require a formal review of residents’ expected scope of practice during international rotations.

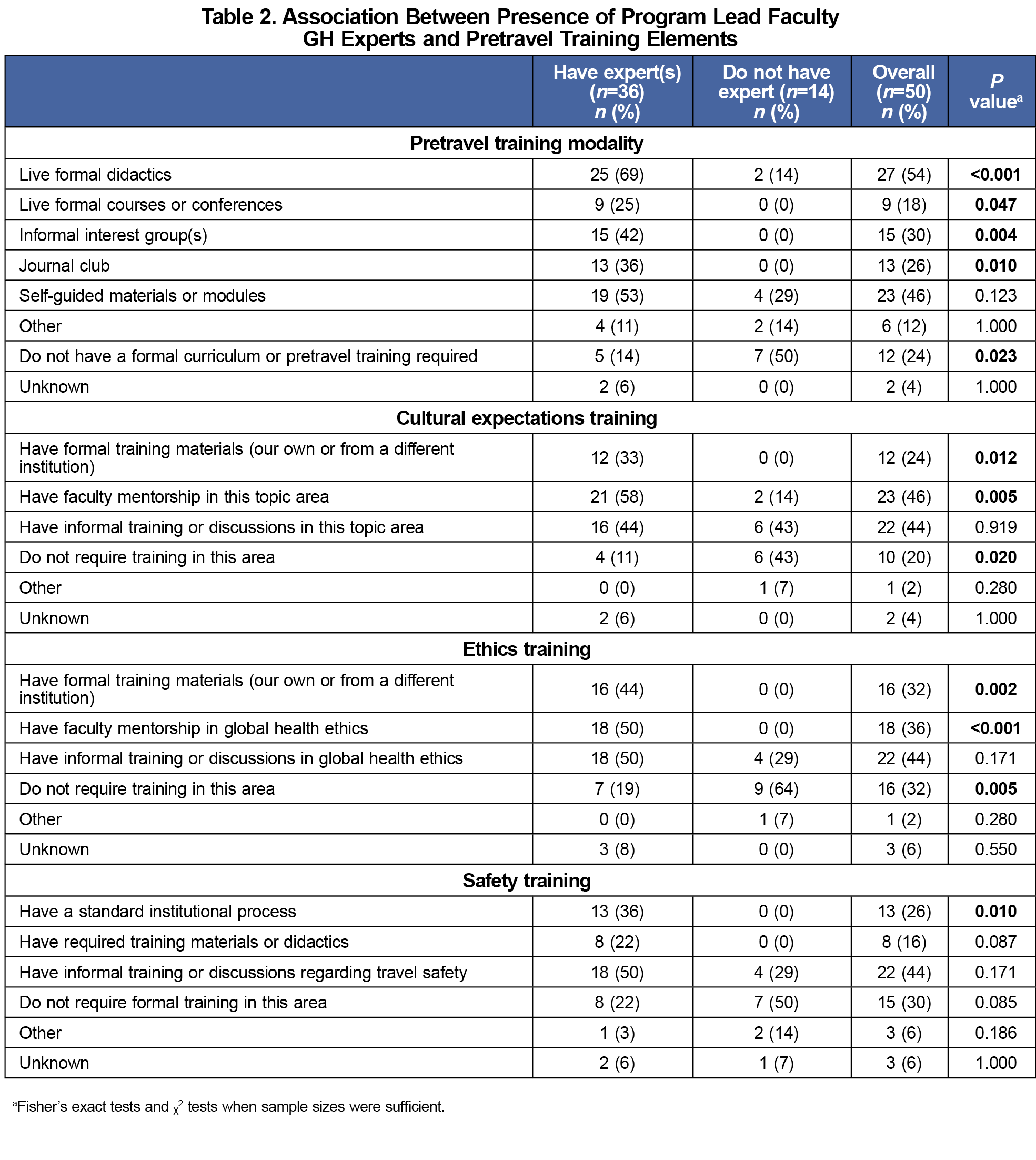

Table 2 shows program frequencies for pretravel training modalities, cultural expectations trainings, ethics trainings, and safety trainings overall and by presence/absence of designated GH faculty that are experts. We allowed for programs to self-define the term “expert” in global health because there is not a widely accepted standard definition of the term.27 Participants were allowed to select all that applied for item rows in Table 2. The “Overall” column has the frequency and percentage of 50 programs analyzed. Live, formal didactics (54%) and self-guided trainings (46%) were the most common pretravel training modality, with 24% having no pretravel training. The two columns for “Have experts” and “Do not have experts” for each item are one-half of a 2x2 contingency table for that item. Live formal didactics were employed at 25/36 (69%) of programs that have GH faculty experts compared to 2/14 (14%) of programs without experts (P<.001). Live, formal courses, informal interest groups, and journal clubs were not used by programs without a recognized GH expert. Self-guided materials/modules were used at 53% of programs with experts compared to 29% without experts, however this sample size with a prevalence ratio of 1.83 was not statistically significant (P=.123). The average number of training modes used was 1.9 (SD=1.6, range 0-5, median=1). Faculty mentorship in cultural expectations was provided by 46% of programs, and this was more common at programs with experts (58%) than at those without experts (14%, P=.005). One-third of programs had formal cultural expectations training compared to none at programs without experts. Ethics training and faculty ethics mentorship was also completely lacking at programs without experts. Informal GH ethics trainings was the most common method used overall (44%), and ≤50% of programs with experts had formal or informal ethics training or mentorship. Thirty percent of programs did not require formal pretravel safety training, and informal trainings were the most common method used (44%). Out of 20 possible training categories in Table 2, programs with experts offered an average of 6.4 (SD=3.8) and programs without experts offered an average of 2.0 (SD=1.5, P<.001 Wilcoxon rank sum test).

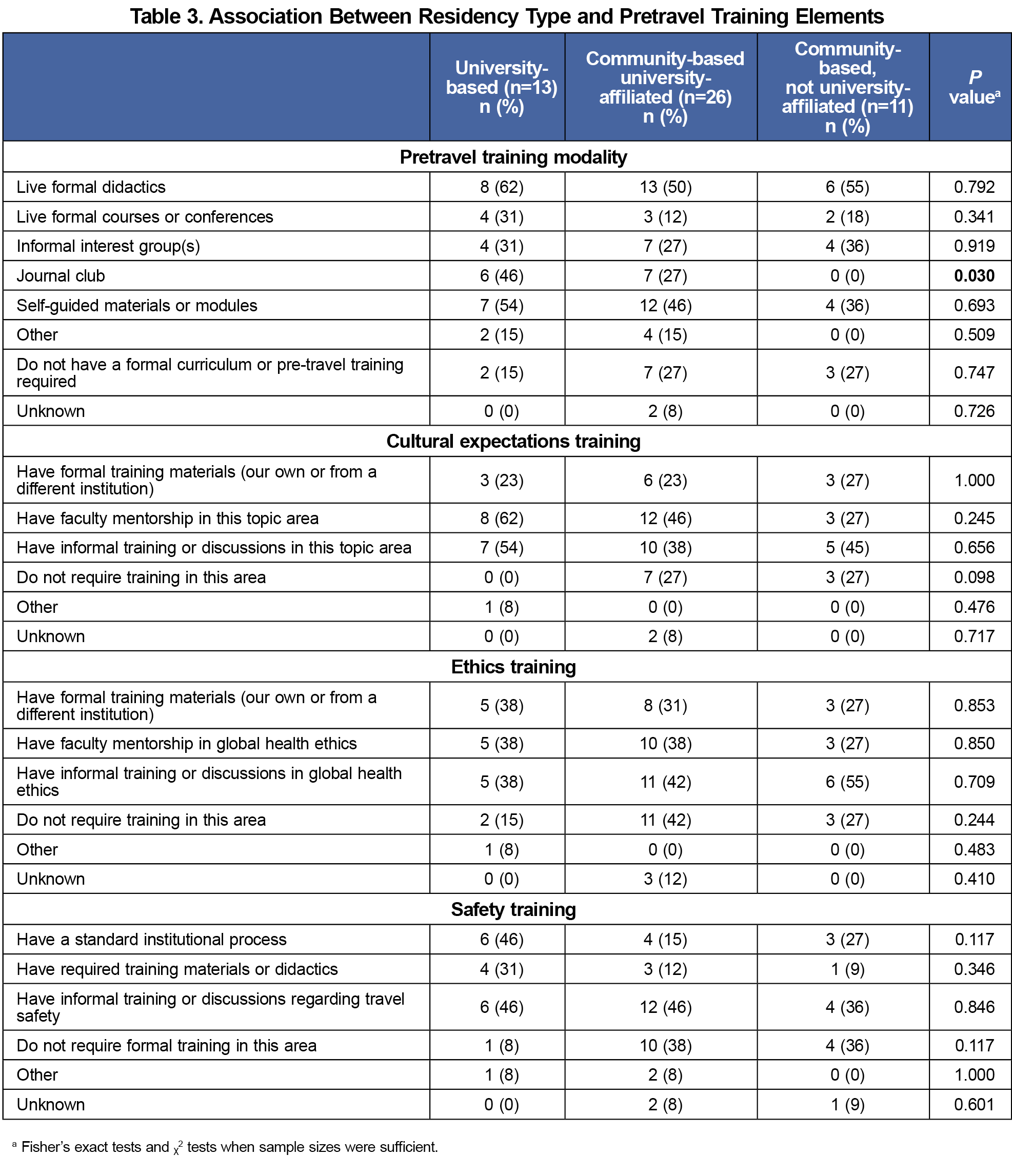

Table 3 shows results from our analysis of program frequencies for pretravel training modalities, cultural expectations trainings, ethics trainings, and safety trainings overall and by residency type. Table 3 layout follows Table 2 with columns for residency type, university-based, community-based university-affiliated, and community-based not university-affiliated, and without the redundant overall column. Availability of journal club when residency programs had a university affiliation was the only pretravel training element that differed significantly among program types.

In supplemental analyses that explored associations among program characteristics from Table 1, there was no significant difference in the program size, age, region, role of respondent, time in role, existence of international global health training opportunities, or presence of at least one expert faculty lead by type of residency program. However, 56% of programs with expert faculty had a process to review residents’ expected scope of practice compared to 7% of programs without expert faculty (P=.001).

In this convenience sample, responding programs with an expert GH faculty lead were more likely to have formal GH curriculum or pretravel training, and the number of trainings offered was greater than programs without an expert GH faculty lead. The GH curriculum offered at these programs is also more likely to include pretravel elements recommended by the WEIGHT ethical best practices for GH training, such as formal cultural expectations, ethics training, and standard safety training.

One major limitation to our study is lack of definition around the “expertise” of global health leads, which is an area to consider for future studies. Another limitation is the convenience sampling method that may not be representative of all US FM residency programs. Potential duplication of program representation by different respondents is also a concern, although we reviewed the data, and only found one that appeared to be a duplicate.

Residency programs should consider designating and funding a lead faculty (who has experience in global health work) to formalize GH curriculum with WEIGHT ethical best practices and ensure residents receive mentorship and feedback in alignment with Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competency requirements (eg, IV.B.1.d).(1).(a) “Demonstrating competence in identifying strengths, deficiencies, and limits in one’s knowledge and expertise”; IV.B.1.f).(1).(a) “Working effectively in various health care delivery settings and systems relevant to their clinical specialty”).28 The current study suggests significant gaps in alignment with these standards. The availability of curriculum toolkits and shared resources specific to FM residency programs may help with GH training standardization, especially for programs without GH expert faculty.29,30 Programs may find existing checklist type resources helpful in implementation.16,31

References

- Kickbusch I. Global health diplomacy: how foreign policy can influence health. BMJ. 2011;342(jun10 1):d3154. doi:10.1136/bmj.d3154

- Beaglehole R, Bonita R. What is global health? Glob Health Action. 2010;3(1):5142. doi:10.3402/gha.v3i0.5142

- Lauriola P, Crabbe H, Behbod B, et al. Advancing global health through environmental and public health tracking. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):1976. doi:10.3390/ijerph17061976

- de Souza JA, Hunt B, Asirwa FC, Adebamowo C, Lopes G. Global health equity: cancer care outcome disparities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(1):6-13. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.62.2860

- Galea S, Abdalla SM. Data to improve global health equity-key challenges. JAMA Health Forum. 2023;4(11):e234433. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2023.4433

- Ye Y, Zhang Q, Wei X, Cao Z, Yuan HY, Zeng DD. Equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines makes a life-saving difference to all countries. Nat Hum Behav. 2022;6(2):207-216. doi:10.1038/s41562-022-01289-8

- Prasad S, Aldrink M, Compton B, et al. Global health partnerships and the Brocher Declaration: principles for ethical short-term engagements in global health. Ann Glob Health. 2022;88(1):31. doi:10.5334/aogh.3577

- Crump JA, Sugarman J; Working Group on Ethics Guidelines for Global Health Training (WEIGHT). Ethics and best practice guidelines for training experiences in global health. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83(6):1178-1182. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0527

- Loh LC, Cherniak W, Dreifuss BA, Dacso MM, Lin HC, Evert J. Short term global health experiences and local partnership models: a framework. Global Health. 2015;11(1):50. doi:10.1186/s12992-015-0135-7

- Anderson FWJ, Wansom T. Beyond medical tourism: authentic engagement in global health. Virtual Mentor. 2009;11(7):506-510. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2009.11.7.medu1-0907

- Yarmoshuk AN, Cole DC, Mwangu M, Guantai AN, Zarowsky C. Reciprocity in international interuniversity global health partnerships. High Educ. 2020;79(3):395-414. doi:10.1007/s10734-019-00416-1

- Cash-Gibson L, Rojas-Gualdrón DF, Pericàs JM, Benach J. Inequalities in global health inequalities research: A 50-year bibliometric analysis (1966-2015). PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0191901. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191901

- Franzen SRP, Chandler C, Lang T. Health research capacity development in low and middle income countries: reality or rhetoric? A systematic meta-narrative review of the qualitative literature. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e012332. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012332

- Yarmoshuk AN, Guantai AN, Mwangu M, Cole DC, Zarowsky C. What makes international global health university partnerships higher-value? An examination of partnership types and activities favoured at four east african universities. Ann Glob Health. 2018;84(1):139-150. doi:10.29024/aogh.20

- Heck JE, Bazemore A, Diller P. The shoulder to shoulder model-channeling medical volunteerism toward sustainable health change. Fam Med. 2007;39(9):644-650.

- Chang KZ, Gracey K, Lamparello B, Nandawula B, Pandhi N. Global health training collaborations: lessons learned and best practices. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;106(2):412-418. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.21-0193

- De Visser A, Hatfield J, Ellaway R, et al. Global health electives: ethical engagement in building global health capacity. Medical Teacher. Published online February 21, 2020:1-8. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2020.1724920

- Schultz SH, Rousseau S. International health training in family practice residency programs. Fam Med. 1998;30(1):29-33.

- Hernandez R, Sevilla Martir JF, Van Durme DJ, et al. Global health in family medicine residency programs: a nationwide survey of us residency directors: a CERA study. Fam Med. 2016;48(7):532-537.

- Drain PK, Primack A, Hunt DD, Fawzi WW, Holmes KK, Gardner P. Global health in medical education: a call for more training and opportunities. Acad Med. 2007;82(3):226-230. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180305cf9

- Slifko SE, Vielot NA, Becker-Dreps S, Pathman DE, Myers JG, Carlough M. Students with global experiences during medical school are more likely to work in settings that focus on the underserved: an observational study from a public U.S. institution. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):552. doi:10.1186/s12909-021-02975-3

- Drain PK, Holmes KK, Skeff KM, Hall TL, Gardner P. Global health training and international clinical rotations during residency: current status, needs, and opportunities. Acad Med. 2009;84(3):320-325. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181970a37

- Grissom MO, Iroku-Malize T, Peila R, Perez M, Philippe N. Mapping residency global health experiences to the ACGME family medicine milestones. Fam Med. 2017;49(7):553-557.

- Porter M, Mims L, Garven C, Gavin J, Carek P, Diaz V. International health experiences in family medicine residency training. Fam Med. 2016;48(2):114-120.

- Lawrence CE, Dunkel L, McEver M, et al. A REDCap-based model for electronic consent (eConsent): moving toward a more personalized consent. J Clin Transl Sci. 2020;4(4):345-353. doi:10.1017/cts.2020.30

- Chang KZ, Bull L, Hernandez R, Aldulaimi S, Myers O, Johnston E. Global health residency program curriculum survey. STFM Resource Library. 2024. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://connect.stfm.org/viewdocument/global-health-residency-program-cur?CommunityKey=1ff91976-09bc-4e95-aad0-63cea0c42e5d

- Ojiako CP, Weekes-Richemond L, Dubula-Majola V, Wangari MC. Who is a global health expert? PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023;3(8):e0002269. doi:10.1371/journal.pgph.0002269

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine (effective July 1, 2024). Accessed March 2, 2025. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/120_familymedicine_2024.pdf

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Global Health Toolkit. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.stfm.org/globalhealthtoolkit

- Global Health Competencies Toolkit. Consortium of Universities for Global Health. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.cugh.org/online-tools/competencies-toolkit/

- Aldulaimi S, McCurry V. Ethical considerations when sending medical trainees abroad for global health experiences. Ann Glob Health. 2017;83(2):356-358. doi:10.1016/j.aogh.2017.03.001

There are no comments for this article.