Background and Objectives: Physician burnout is well described in the literature. In response, experts are now shifting to try to understand physician resiliency. We sought to better understand burnout and resiliency from the perspective of family medicine residents through the qualitative analysis of photographs and discussion.

Methods: We used Photovoice, a qualitative research method, to understand how residents describe and cope with burnout. Faculty assigned residents at a Midwest family medicine residency program to take photographs and provide captions that reflected personal experiences of burnout and resilience. Residents viewed the collective photographs and discussed their impact during three audio-recorded small-group sessions. Researchers qualitatively analyzed the captions and recordings using a hermeneutic phenomenology approach, and analyzed the visual content of the photographs using a standardized rubric.

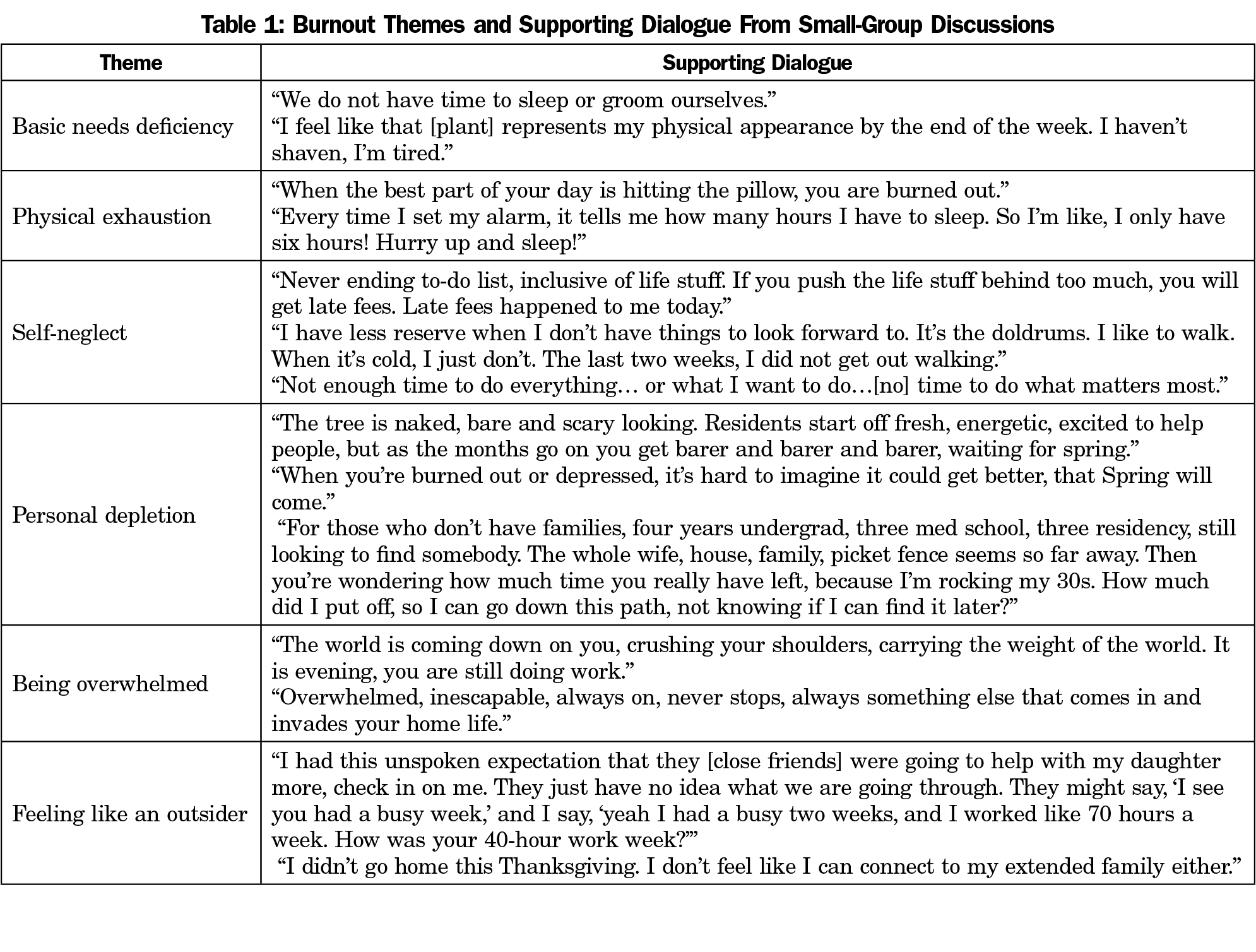

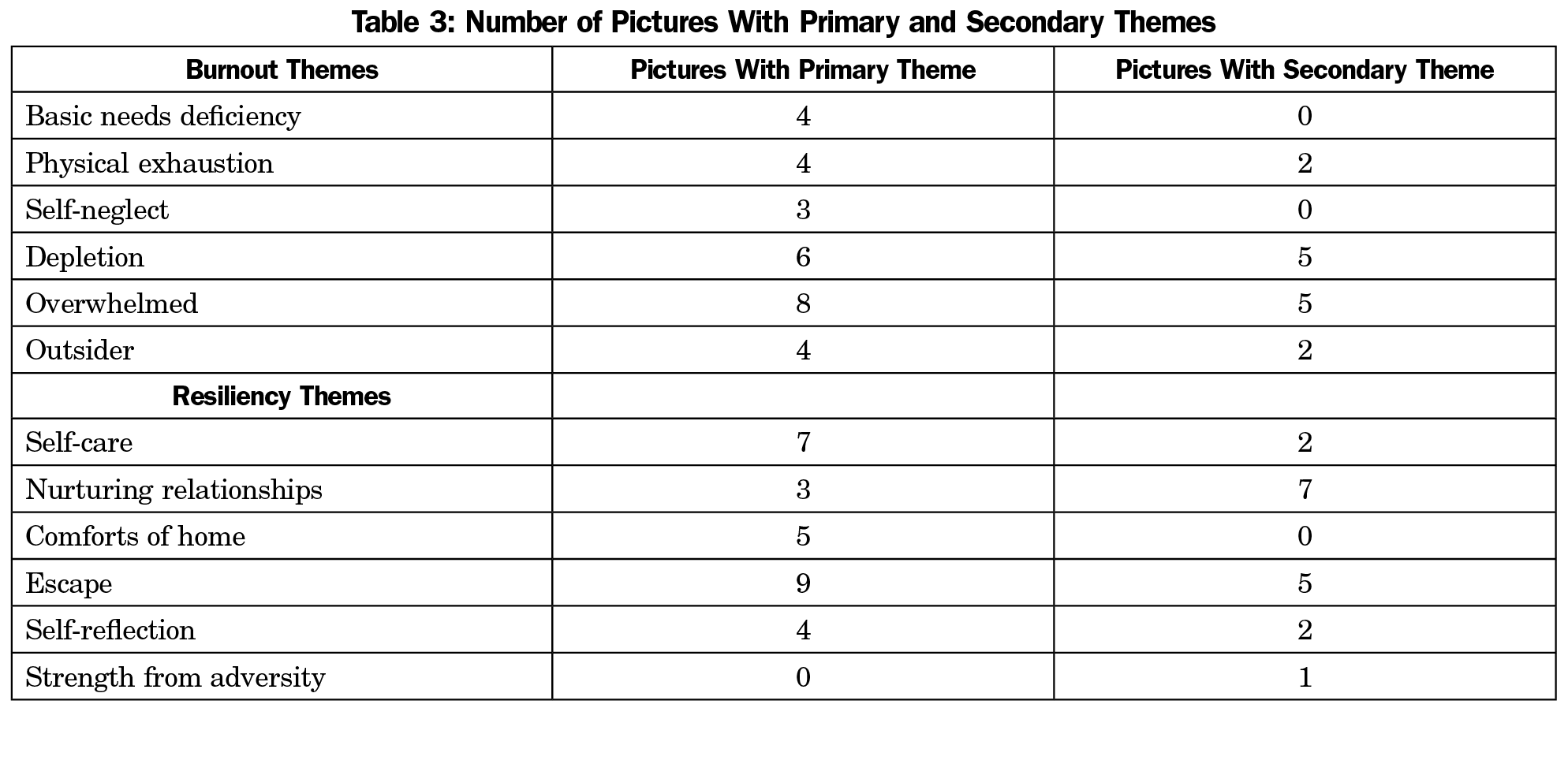

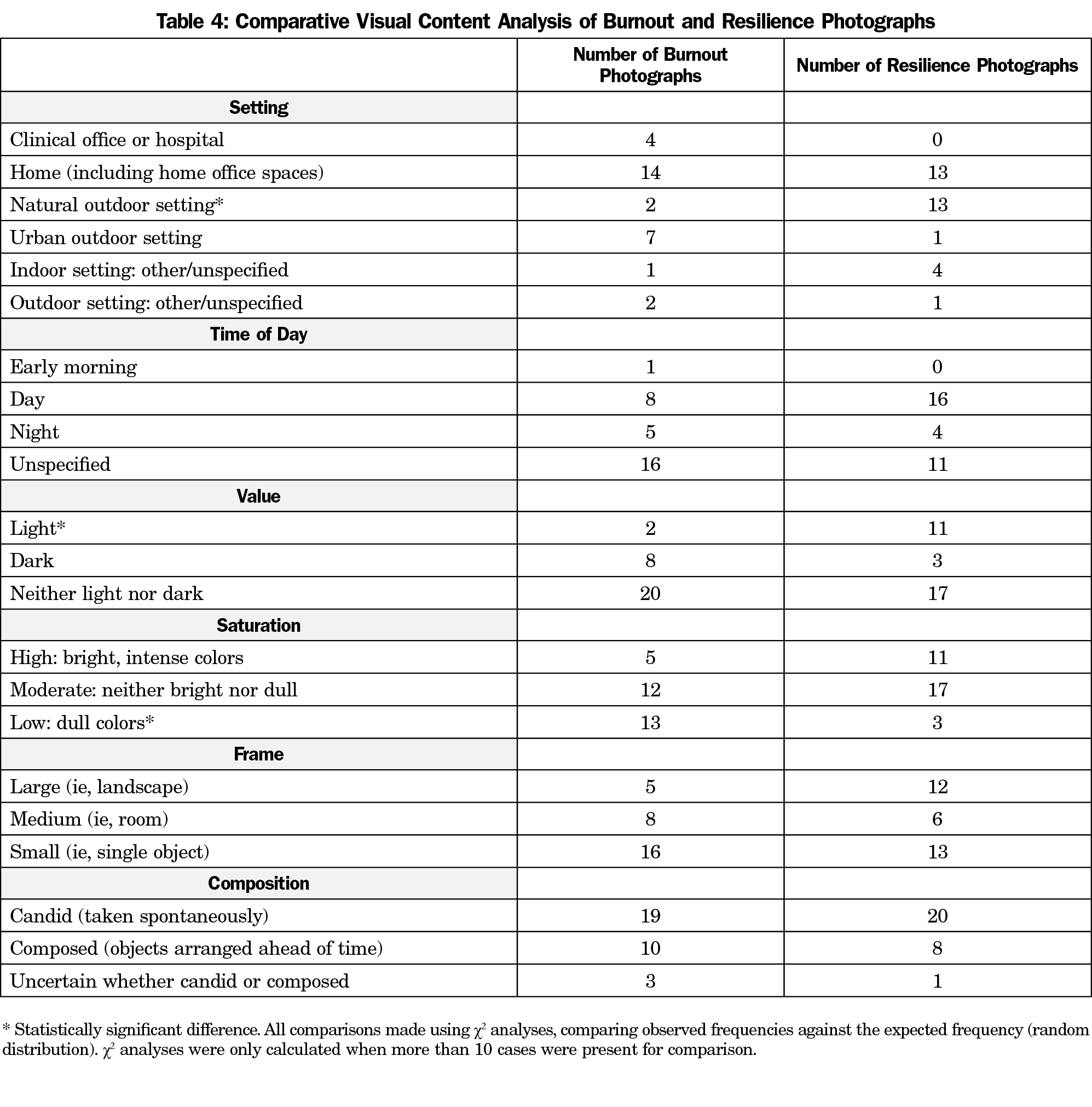

Results: We identified six themes for the resident description of burnout: basic needs deficiency, physical exhaustion, self-neglect, personal depletion, being overwhelmed, and feeling like an outsider. Six themes were also identified for cultivating resilience: self-care, nurturing relationships, seeking the comforts of home, escaping to refuel, self-reflection, and identifying strengths from adversities. Resilience pictures were more likely to have been taken in a natural setting; burnout photographs were duller in color.

Conclusions: Family medicine residents experience burnout in specific, unique ways, and are able to identify common sources of resilience. Family medicine educators can use the Photovoice methodology to help residents capture their personal experiences of burnout, share their experiences with peers, and discover sources of resilience.

Physician burnout is an area of intense research. In their seminal paper comparing physician burnout rates from 2014 to 2011, Shanafelt et al report that despite increased attention to this issue, rates of physician burnout continue to rise, and satisfaction with work-life balance is falling.1 The 2020 annual Medscape Physician Burnout, Depression and Suicide Report of more than 15,000 physicians corroborates these findings.2 High burnout rates and career choice regret have also been documented in medical residents.3,4

With substantial research into the multifaceted causal factors of burnout, systems issues now take center stage as key drivers of distress; burnout is no longer perceived as an individual problem.4-6 The challenge for educators and physician leaders is to understand and address the systemic factors, while simultaneously helping physicians build resilience to endure a broken system.

Burnout is frequently measured using surveys. However, the scripted language and categories of survey tools constrain individual expression and prevent physicians from self-defining burnout. This limits our understanding of systemic factors contributing to physician distress.7

Previous qualitative studies have described multiple sources of resident burnout, including feeling underequipped and overwhelmed, disrupted personal relationships, high workload, lack of autonomy, and exhaustion.8-10 Residents cultivate resilience through developing professional identity, connecting to peers and role models, practicing self-care, and seeking comfort.9,11 The purpose of this study was to expand our understanding of family medicine residents’ perspectives on how they define burnout and strategies to overcome it, beyond the constraints of standardized measures.

The study is unique in its use of Photovoice methodology. Photovoice is a participatory research methodology that provides a way for people to “identify, represent, and enhance their communities through a photographic technique.”11 It gives people the opportunity to represent, in images, ideas that may be hard to express in words. This method was chosen in order to facilitate structured group conversation around complex, abstract concepts, and to add to existing knowledge about resident burnout and resilience by employing a novel approach.

Participants and Procedures

Participants were family medicine residents in a university-affiliated residency program in the United States. Residents were given information about the project, basic instruction in photography, and information about photography ethics13, 14 in the context of Photovoice. Residents were instructed not to include identifiable individuals, patient data, body parts that could be construed as dehumanizing, or sexually explicit images in their images. Each resident was asked to take and electronically submit two photographs, with each responding to one of two questions:

- What is burnout?

- How do I prevent or overcome burnout?

They were asked to also submit a brief statement explaining why they chose the images.

Each participating resident then attended one of three Photovoice small-group (6-10 participants) discussions. One group had only interns. Second- and third year residents analyzed second- and third-year photographs; first-year residents analyzed primarily first-year photographs, but also examined selected upper-level photographs.

During the group sessions, anonymous photographs were posted on the walls with their captions, and residents reviewed them independently. To facilitate group discussion, photographs and their captions were projected using PowerPoint slides. Finally, residents discussed the major themes of the photographs as a whole and reflected on what had been learned during the session. Sessions were audio recorded. At least two of the three researchers were present for each session and aided in facilitating group discussion. Residents consented to participation and the Sparrow Hospital Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Analysis

The research team consisted of two family physicians and a social worker. Two of the researchers had expertise in behavioral medicine; the third was an experienced qualitative researcher with formal Photovoice training. We performed data analysis using a hermeneutic phenomenology approach.12 Hermeneutic phenomenology aims to describe a phenomenon (burnout and resiliency) and find its meaning in the context of individuals’ lived experiences, and recognizes researchers’ experiences with the subject in the process of interpretation. This aligned with the goal of better understanding residents’ burnout in the context of both their learning environment and their personal lives.

We performed the coding primarily using paper, markers, and sticky notes. We developed initial themes through group discussion based on the photographs, captions, and recollections of the Photovoice sessions. We assigned each picture a primary theme with secondary themes also noted. We used these initial themes to construct a coding manual. We then listened to audio recordings of the discussion sections, taking detailed notes and transcribing key portions of the discussion; two researchers independently analyzed each recording and reached consensus when different interpretations occurred.

During the coding process, we openly examined our own assumptions about burnout and resiliency using a continuous process of reflexivity.12 We met regularly and reviewed our work in detail. We also listened to the audio recordings for disconfirming or contradictory information and for additional themes. We iteratively and collaboratively discussed the emergent themes until saturation was reached.

We analyzed the photographic images using a visual content analysis approach. We developed a standardized scoring rubric for content analysis based on compositional framework, as described by Rose.13 We independently analyzed the photographs using this standardized scoring rubric for setting (place), time of day, value (lightness or darkness), saturation (brightness or dullness), frame (eg, landscape), and composition (staged or candid).13 Where two of the researchers disagreed, the third researcher analyzed the images and made a final determination. We then quantitatively described the differences in the visual analysis between the burnout and resilience images. We used χ2 analyses to determine whether the differences were statistically significant.

In total we analyzed 29 visual images and captions for burnout and 28 images and captions for resiliency. One image was removed because it included an identifiable image of an individual. Of these, nine from each of the categories were photographs from interns; the rest were from second- and third-year residents.

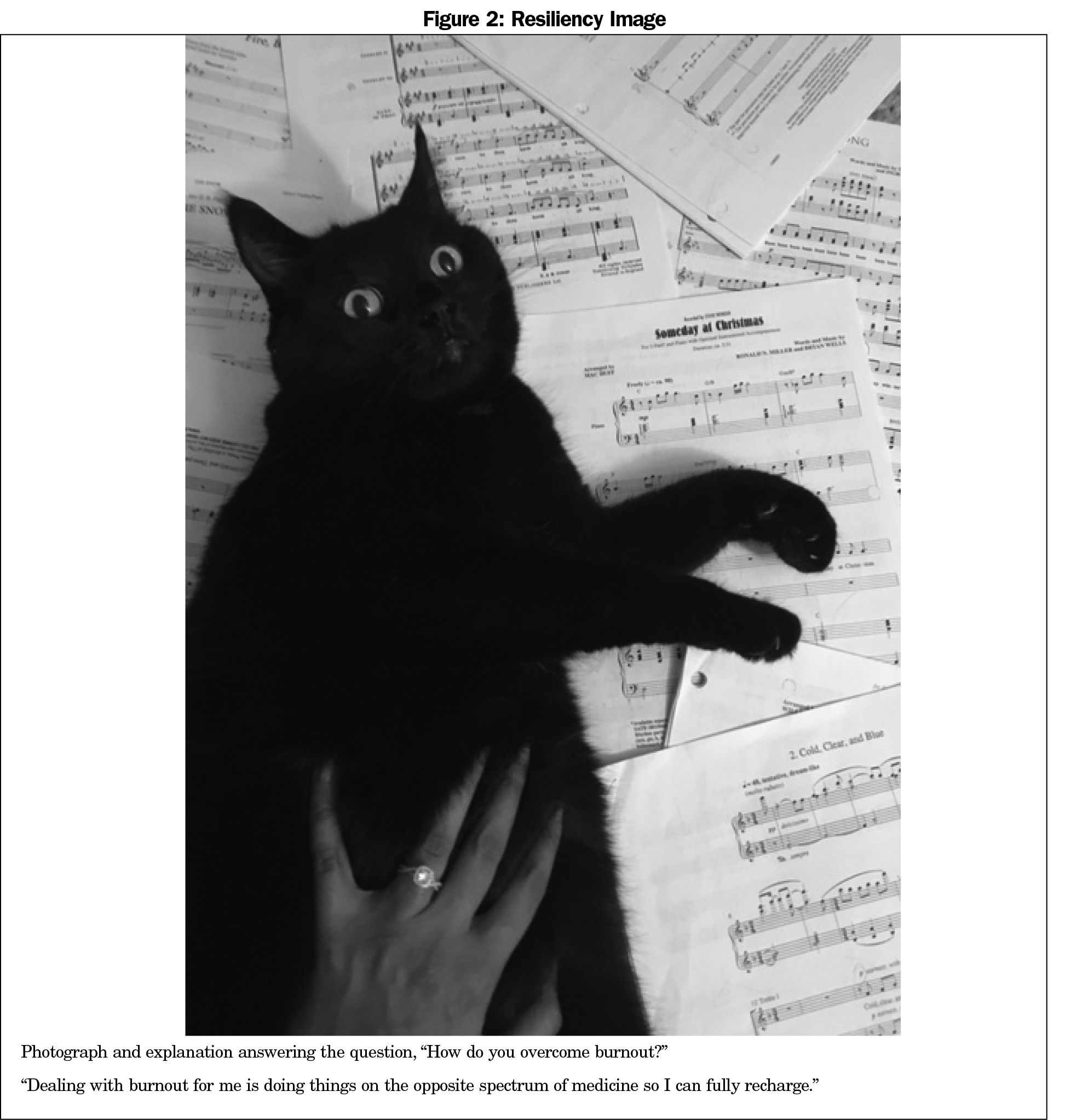

We identified six themes describing burnout and six themes describing resiliency. Examples of supporting dialogue for each theme from the small group discussions are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Several photographs reflected more than one theme (Table 3). Figures 1 and 2 represent examples of burnout and resiliency photographs.

What is Burnout? Identified Themes

Basic Needs Deficiency. Residents described an inability to attend to basic needs due to lack of time and energy. This included common activities of daily living like doing the dishes, buying groceries, or cleaning one’s living space. Images depicted stacks of dishes, laundry piling up on the floor, and unmade beds. Captions noted living in these conditions for a prolonged time period (weeks). All of the primary pictures describing this theme were from interns.

Physical Exhaustion. Images and dialogue regarding physical exhaustion went beyond being tired. There was a repeated image of coffee and a caption mentioned the need for caffeine to mask the physical aspects of burnout. One image depicted several alarms being set and snoozed, and another showed a resident falling asleep while charting on the computer. During the discussions, many commented on how setting alarms was necessary but anxiety provoking because it set a limit on the amount of sleep one could get, which was never enough.

Self-neglect. Self-neglect was defined as prioritizing others over self as a means of survival. Images in this section were highly symbolic. One depicted a car that had been in crash with only part of it being damaged. Residents described this damaged car as symbolic of how they might be falling apart but still have to keep going. Another showed symbols of work (a white coat and a stethoscope) and a baby (bottles) stacked on top of an alarm clock and a yoga mat. The resident described not being able to care for herself (symbolized by the yoga mat) because of the demands of her newborn and her patients. A third image was of a neglected house plant, dying from lack of water. A common thread in discussion was the idea that you could usually sacrifice a little and be okay, but after a while “you crash and burn.”

Personal Depletion. We defined personal depletion as a loss of energy and resources leading to a colorless, lifeless existence. This is associated with feelings of detachment. Images showed concrete buildings, colorless skies, and barren trees. One caption stated, “Burnout occurs when we allow a certain aspect of our lives to drain more energy than we get in return.” Many comments alluded to the profusion of “meaningless” paperwork and charting tasks. Augmenting a picture of a burned hillside, one resident stated, “depletion of energy, help and resources can make someone become exhausted of all their natural beauty.”

In the discussions, we identified several statements that captured the feeling of longing for something. It was felt that this was a result of personal depletion. Dialogue captured residents longing to see daylight, longing to spend time with their children, and longing for the joy in medicine.

Being Overwhelmed. This theme had the most supporting images. The concept of being overwhelmed included endless demands that force one to multitask and prioritize competing tasks and responsibilities. It is exacerbated by the need to have constant vigilance on tasks, such as responding to pages, with no break for refueling. Residents chose images depicting information overload, symbolized by stacks of journals, books, papers, pagers, phones, and multiple computer screens. Many of the captions referenced feeling burned out when one gets behind in one’s work, which leads to “becoming detached from one’s work and just going through the motions.”

A significant portion of the discussion supported this theme. Residents felt “claustrophobic” because of the workload. Work was described as “unrelenting.” They described feeling “inadequate” and “not knowing enough” to manage the expectations. The multitude of competing demands was also overwhelming, making them feel “scatterbrained.”

Feeling Like an Outsider. Residents described feeling like “outsiders,” missing out on the life happening around them while they are at work. They felt isolated and disconnected from nonmedical friends and families. Three images showed the outside of buildings with references to not knowing what was going on inside, including one poignant image of a resident standing outside a sleeping household after dark. Another photographer took the perspective of being “stuck” inside her house with “no time for anything else.” Dialogue in the discussions was personal. Residents referenced friends and family not understanding their commitments, missing key family events, and neglected friendships. There was a sense that “life is passing by.”

How Do I Prevent or Overcome Burnout? Identified Resiliency Themes

Self-care. Residents recognized self-care as an important key to resilience. Self-care was defined as intentionally setting aside regular time to do things that are personally gratifying and recharging, including exploring hobbies and interests. Images in these pictures contained representations of self-care activities, such as sheet music (Figure 2), board games, and fishing.

Discussion and captions referenced deliberately taking time to practice these activities in order to combat burnout. “Balance between our work lives, family lives, and social lives…remembering to allocate time for each is the key.” One symbolic picture showed a thriving house plant. Residents remarked that it takes the right amount of fertilizer, water, and sun to build resilience.

Nurturing Relationships. Relationships, and the act of tending to them and being nurtured by them, builds resiliency. The residents shared images and conversation depicting their beliefs that connection and strength can come from spending time with family, friends, and pets. Many images were symbolic: a resident’s family’s hands joining together in a “go team” pose, a family’s holiday stockings hanging together, an engagement ring (Figure 2). Another image was a close-up of homemade cookies with an accompanying caption: “Finding ways to bring joy to others.” Several pictures portrayed pets; captions and dialogue reflected the importance of connecting with animals for their unconditional love.

Seeking the Comforts of Home. The comforts of home theme captures the basic needs that must be met in order to build resilience. Food, shelter, and sleep are simple needs that must be fulfilled in order to learn and grow. Four of the five primary images in this theme were from the intern class. Three of these pictures depicted couches and blankets, where the residents would rest and watch TV or play video games. Discussion of these images evoked conversations about the coziness and restfulness of home.

Escaping to Refuel. Escape, defined as planned extended leave from regular activities with the intention of recharging and relaxing, was the most common theme for resident pictures on resiliency. All nine of the primary pictures were from upper-level residents. Half depicted destinations that required flying to achieve the escape. The others showed images of local lakes, fields, and woods. In the discussion and the captions, many mentioned nature as an important element that allowed for recharging and freedom from the restrictions of work. One resident identified the joy in “finding a new trail” at a local park, described as “nourishing.” Images in this theme had significant overlap with the nurturing relationships theme.

Self-reflection. Self-reflection activities are done with the purpose of discovering value and meaning in one’s own life. This was represented in images and captions that described finding stillness and perspective-taking. Some residents discussed creating time in their day for rituals to help them be in the moment, for example, “the tea hits my lips and I feel instantly calm.”

Identifying Strengths From Adversity. Strength from adversity was the only theme that was identified from review of the discussion and not from initial review of the photographs. At several points during the discussions, residents referenced going through challenges and struggles and being stronger because of these experiences. One image of a burning fire prompted discussion about the regrowth that occurs from the ashes. There was recognition that the difficult experiences of residency provide fertile ground for learning, personal growth, and professional advancement.

Visual Content Analysis

Table 4 summarizes the comparative visual analysis of the photographs. As discussed above, resilience photographs were significantly more likely to take place in a natural outdoor setting (P=.010) and were lighter in value (P=.026). In contrast, burnout photos were more likely to have low saturation (dull colors, P=.012). Although not significant, there was a trend toward burnout photos being taken more at work or an urban outdoor setting and having darker value. Resilience photographs trended toward being taken during the day and having high saturation (bright colors). Burnout and resilience photos were equally likely to have been taken at home.

Our study aimed to allow residents to define burnout from their own perspective and collectively discuss strategies to bolster resilience. The findings augment the results of previous qualitative researchers who have explored sources of resident burnout and the development of resident resilience.8-10,14 Additionally, the burnout themes defined in this study expand on the categories used in the Maslach Burnout Inventory17 of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment. Though often used to support research in burnout, this inventory is 40 years old and not specific to medicine. The themes offered by the residents portray a more nuanced description of the experience of burnout in graduate medical education.

The researchers noted some divergence of burnout and resilience themes between interns and upper-level residents. Specifically, all of the primary photographs in the basic needs deficiency and four out of five primary photographs in the comforts of home theme were submitted by interns. This highlights the tension in residency training where the development of learners is constrained by the structure of the system itself. Interns described their struggle to meet basic physiologic needs. Maslow’s theory of motivation states meeting these needs is essential to development.15 In this analysis, interns longed for sleep, while senior residents were more likely to anticipate a relaxing vacation.

The process illuminated the concepts successfully because the images served as catalysts for small-group dialogue. The clear differences in lighting and color easily differentiated the burnout from resilience images and evoked an emotional response. During the discussions, the residents described shared experiences that previously were perceived as private, individual flaws. Additionally, the participants taught one another self-care skills and rituals. The small-group environment itself cultivated resilience through connection to peers and comfort seeking.9, 11 We are pursuing further research on the impact of this experiential research as an educational tool.

Limitations

This was a single-institution study, which may limit its generalizability. The researchers were also the facilitators of the Photovoice sessions and had previous experiences and knowledge of burnout, creating inherent subjectivity. We acknowledged our subjectivity through a continuous process of reflexivity12 and aimed to maximize the quality of the analysis by seeking disconfirming evidence, triangulating multiple data sources (images, captions, recordings), and ensuring that at least two researchers analyzed each portion of the data. The information shared by residents may also have been filtered based on their comfort level and sense of safety. The dual role of facilitator and faculty/supervisor was recognized as potentially impacting resident responses. Specifically, we noted that no residents included any images or discussion of substance use.2

The study findings reflect an urgent call to action for systems to examine and address factors that contribute physician burnout. The power of this project will be magnified when it is replicated in other medical education settings. Images from similar projects should be shared throughout health systems and community settings to raise awareness and promote culture change in response to physician burnout. As a next step, the authors have initiated a collaboration to expand this research and develop a national repository of photographs to further illustrate health care professional burnout and resilience.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: This study was previously presented as follows:

- Odom A. Romain A. Using Photovoice to Reflect on Resident Burnout and Resiliency. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference, April 2019, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- Odom A. Romain A. Reflecting on Burnout and Changing Culture through use of Photovoice. Forum for Behavioral Science in Family Medicine, October 2018, Chicago, IL.

- Phillips J, Romain A, Odom A. Using Photovoice to Reflect on Resident Burnout and Resiliency. Learn Serve Lead: Association of American Medical Colleges Annual Conference. Phoenix, AZ.

References

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023

- Kane L. Medscape National Physician Burnout, Depression & Suicide Report 2019. Published January 16, 2019. Accessed November 23, 2021. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056

- Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among US resident physicians. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1114-1130. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.12615

- Rothenberger DA. Physician burnout and well-being: a systematic review and framework for action. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(6):567-576. doi:10.1097/DCR.0000000000000844

- Drummond D. Physician burnout: its origin, symptoms, and five main causes. Fam Pract Manag. 2015;22(5):42-47.

- Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(7):836-848. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.05.007

- Schwenk TL, Gold KJ. Physician burnout-a serious symptom, but of what? JAMA. 2018;320(11):1109-1110. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.11703

- Rutherford K, Oda J. Family medicine residency training and burnout: a qualitative study. Can Med Educ J. 2014;5(1):e13-e23. doi:10.36834/cmej.36664

- Benson NM, Chaukos D, Vestal H, Chad-Friedman EF, Denninger JW, Borba CPC. A qualitative analysis of stress and relaxation themes contributing to burnout in first-year psychiatry and medicine residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(5):630-635. doi:10.1007/s40596-018-0934-2

- Law M, Lam M, Wu D, Veinot P, Mylopoulos M. Changes in personal relationships during residency and their effects on resident wellness: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2017;92(11):1601-1606. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001711

- Wang C, Cash JL, Powers LS. Who knows the streets as well as the homeless? Promoting personal and community action through PhotoVoice. Health Promot Pract. 2000;1(1):81-89. doi:10.1177/152483990000100113

- Bynum W, Varpio L. When I say … hermeneutic phenomenology. Med Educ. 2018;52(3):252-253. doi:10.1111/medu.13414

- Rose G. Visual Methodologies. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2001.

- Winkel AF, Honart AW, Robinson A, Jones AA, Squires A. Thriving in scrubs: a qualitative study of resident resilience. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):53. doi:10.1186/s12978-018-0489-4

- Maslow AH. A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev. 1943;50(4):370-396. doi:10.1037/h0054346

There are no comments for this article.