Background and Objectives: The United States-Mexico border has unique health care challenges due to a range of structural factors. Providers must be trained to address these barriers to improve health outcomes. Family medicine as a specialty has developed various training modalities to address needs for specific content training outside of core curriculum. Our study assessed perceived need, interest, content, and duration of specific border health training (BHT) for family medicine residents.

Methods: Electronic surveys of potential family medicine trainees, faculty, and community physicians assessed appeal, feasibility, preferred content, and duration of BHT. We compared responses from participants from the border region, border states and the rest of the United States in their opinions about modality, duration, content of training, as well as perceived barriers.

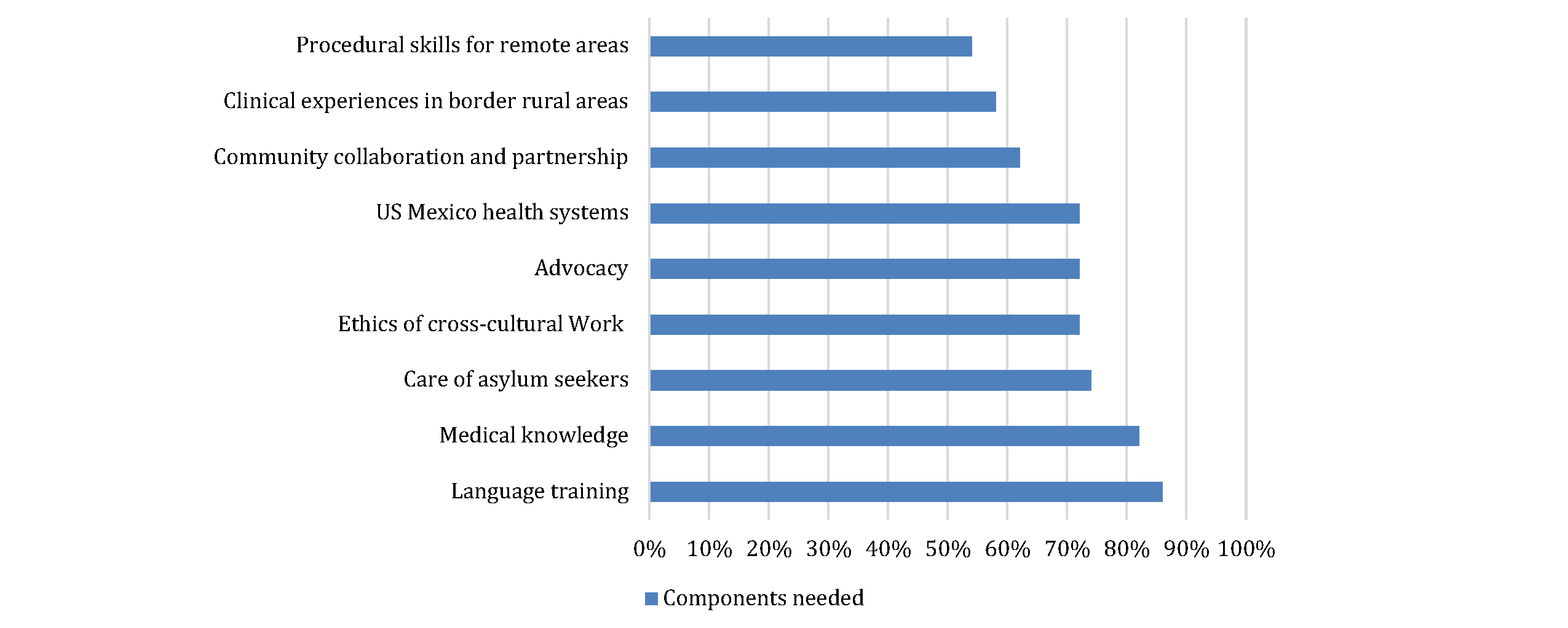

Results: Seventy-four percent of survey participants agreed that primary care on the border is unique; 79% indicated a need for specialized BHT. Most border-region faculty were interested in participating as instructors. Most residents expressed interest in short-term rotation experience, yet most faculty recommended postgraduate fellowship. Respondents selected language training (86%), medical knowledge (82%), care of asylum seekers (74%), ethics of cross-cultural work (72%), and advocacy (72%) as the top-five needed training areas.

Conclusions: Results of this study indicate a perceived need and sufficient interest in a range of BHT formats to warrant developing additional experiences. Developing a variety of training experiences can engage a wider audience interested in this topic; that should be done in a way ensuring maximum benefit to border-region communities.

Border health (BH) is a broad concept including aspects of public health, health care markets, environment, immigration, and binational cooperation. 1, 2 International borders represent intermingling of populations, requiring cooperation between international, federal, state, and local agencies. Definitions vary from “demarcation of sovereign states” 3 to including the entirety of neighboring states. For the United States-Mexico border, most agencies use the 1984 La Paz Agreement defining the area as a 100-kilometer zone north and south of the international boundary. 4, 5 The region is largely rural yet contains two of the ten fastest-growing metropolitan areas in the United States. 6 Recent arrivals of asylum seekers have increased attention among health providers to this area.

Denizens of this long medically-underserved region experience disproportionate rates of disease, including diabetes, HIV, and hepatitis C. 4, 7-10 Policy papers cite poor health outcomes resulting from social barriers including low income, high unemployment, workforce shortages, and higher than national average rates of uninsured/underinsured. 4, 9 Financial barriers contribute to fragmentation of care within the United States, with some seeking care in Mexico. 4, 7 Many unincorporated communities along the border lack infrastucture. 11 International and domestic policy decisions influence the region, particularly impacting communities that are socially dependent on their sister cities across the border. 4, 12 Regional health disparities cannot be addressed if providers are unaware of structural barriers contributing to disparate health outcomes.

Physician shortages are pronounced, with the four US border states ranking in the bottom half of all US states. 13 Data indicate that more than half of family medicine (FM) residents practice within 100 miles of their training site, 14 indicating the importance of availability of residency programs and other postgraduate training opportunities in the border region. Currently, the FREIDA residency database15 shows 130 FM residency programs in border states, 14 of which are located in the border region with three additional programs located just outside this region. More than 121 intern positions are available across all 17 of these border region and near-border region programs.*16 FM residency programs offer a wide scope of training to foster adaptability to future practice. Many programs offer specialized training supplementing their core curriculum with specialized rotations, areas of concentration, specialty tracks, and postresidency fellowships (both accredited and unaccredited). Prior to conducting our study, we conducted a search of PubMed, American Association of Family Physicians (AAFP) residency program listings, presentations at the AAFP Global Health Summit, and attended meetings with the AAFP BH Interest Group. While we identified some residency programs that offer border health training (BHT), we were unable to identify any published systematic assessments of BHT. This study, therefore, addressed the following questions: (1) Is there a perceived need among FM residents and faculty in US-based residency programs for BHT opportunities?; (2) If such training were more widely available, would FM residents be interested in participating?; (3) What do residents and faculty identify as the most critical content for such training?; and (4) What would be the optimal duration? To answer these questions, we designed a study utilizing an online survey of FM faculty and trainees across the United States, including within the border region.

Participants

FM residents, FM residency core faculty, community faculty, and nonteaching physicians were recruited to participate in an online survey. Participants self-identified for each professional subgroup. We excluded non-FM participants.

Recruitment

We used convenience sampling to recruit participants as there was no one specific site that had contact information for all intended participants. To obtain a diverse and inclusive sample, the first two authors distributed surveys with cover letters via multiple listservs and networks including Society of Teachers of Family Medicine, Association of Family Medicine Directors, AAFP, and family medicine program directors. Cover letters asked program directors to share the survey with faculty and residents. Social media networks including Facebook were also used to distribute surveys. Efforts were made to reach all border region FM residency programs by directly contacting those regions’ health care provider networks and residency training programs. Surveys were initially distributed in early June 2019, followed by two waves of reminders ending in early August 2019. Signed consent was waived; however, participants were instructed that clicking “continue to survey” indicated consent to participate in this study. Responses were not linked to any identifying participant information.

Data Collection

Online surveys were designed de novo by three coauthors with extensive professional experience working directly in BH, global health (GH), and developing residency and fellowship training. The initial survey draft was reviewed by additional subject matter experts in BH and postgraduate training, after which revisions were made using Qualtrics software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and piloted with a small group of residents and faculty including fellowship directors; we utilized their feedback to finalize the survey. All participants answered a set of core questions, followed by subsets of questions unique to each professional subgroup. Content covered a range of questions around needs/interest/content and barriers to potential BHT (See Appendix 1 for survey). The survey queried participants’ experiences in the border region and perceptions of health needs compared to other areas of the United States, as well as perceived need for specialized BHT. Those expressing that BHT was unnecessary ended the survey as the remaining questions focused on training duration and content. Each professional subgroup was asked specific questions applicable to their group; for example, learners were asked about interest in receiving BHT and then asked to expand upon their answers.

Analysis

We analyzed survey data using SPSS (SPSS V26, IBM Corporation, 2019). We postcoded responses to questions allowing for open-ended “other” entries, for themes. We eliminated surveys with less than 50% of questions answered from analysis. Based on the categorical or continuous nature of the data, we reviewed initial frequencies using percentages and/or measures of central tendency (eg, means, standard deviations, and medians). Bivariate analyses included χ2 and t tests as appropriate based on the nature of the various data elements and associations to be tested. The first author reviewed open-ended questions to gain additional insight and participants’ responses.

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School reviewed and approved the study and its documents.

Survey respondents included 342 participants: 95 residents, 101 core residency faculty, 61 community teaching physicians, and 85 nonteaching physicians (Table 1 ). We could not calculate a response rate and nonresponse bias due to convenience sampling and lack of a complete assessment of the denominator within each group, and recruitment methods not inclusive of the sampling frame (eg, multiple listservs). Participants responded from 31 states with nearly two-thirds (64%) in border states and almost one-third (31%) specifically from the 100km border region. Over one-quarter (28%) were residents, and just under half (47%) of respondents were involved in teaching.

|

Demographics

|

n (%)

|

|

What is your age?

20-39 years

40-55 years

56-75+ years

|

x

141 (50.9)

92 (33.2)

44 (15.9)

|

|

What is your gender?

Female

Male

Other

|

x

179 (64.6)

94 (33.9)

4 (1.4)

|

|

Which of the following best describes you?

Family medicine resident

Faculty at family medicine residency program

Primary care physician not involved in teaching

Community physician involved in teaching

|

x

95 (27.8)

101 (29.5)

85 (24.9)

61 (17.8)

|

|

What state are you currently working in?

Border state (N=4: CA, AZ, NM, TX)

Arizona

California

New Mexico

Texas

Border region (within 100 km of US/Mexico border)

Nonborder state (N=27 states)

|

x

220 (64.3)

15 (4.4)

34 (9.9)

34 (9.9)

137 (40.1)

68 (20.9)

122 (35.7)

|

|

What is your current working relationship with the border region?

Currently work full-time in the border region

Currently work part-time in the border region

Have worked/lived/trained in the border region in the past but no longer work/live there

Do not/have never worked in the border region

Other

|

x

62 (18.1)

6 (1.8)

56 (16.4)

213 (62.3)

5 (1.5)

|

Perception of Need

Nearly three-quarters (74%) of survey participants reported that primary care was different along the US-Mexico border than in other regions of the country. Almost 80% reported a need for specialized BHT focusing on regional health needs. Need was reported to be even higher among those working in the border region, with 84% stating there was a need for specialized BHT compared to those in border states (78%) or other regions (79%).

Skills Needed

Respondents selected language training (86%), medical knowledge (82%), care of asylum seekers (74%), ethics of cross-cultural work (72%), and advocacy (72%) as the top-five needed training areas (see Figure 1 for all ranked options). Additionally, open-ended questions suggested education on legal aspects of migration/asylum law such as forensic asylum evaluations, and interactions with agencies involved in immigration and customs.

Best Format for BHT

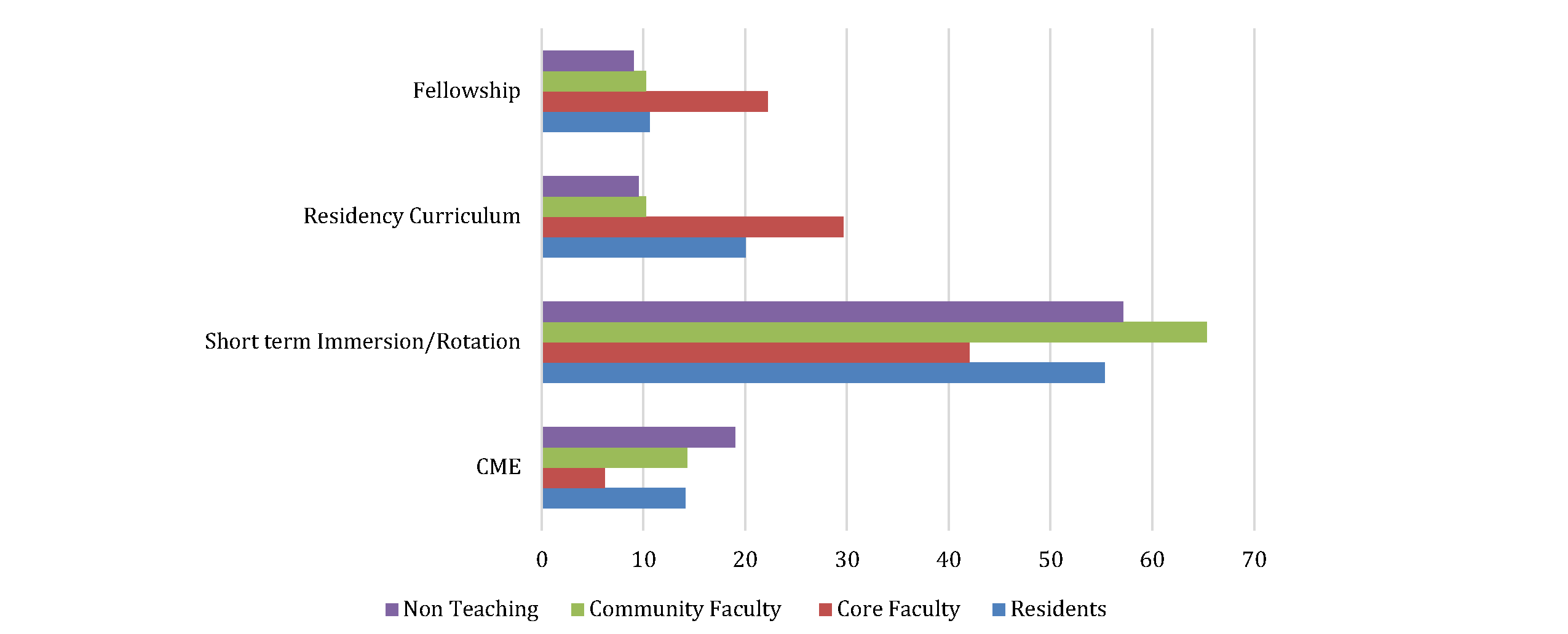

Just over one-half (54%) of participants preferred short-term immersion experiences or rotations. Other possible formats were residency tracks (19%), fellowships (15%), and intense continuing medical education (CME) courses (13%; Figure 2). Core residency faculty favored fellowships or residency curriculum (50%). At least some residents (10%) did express interest in a fellowship. Community faculty and nonteaching physicians generally preferred CME format.

Length of Training

Nearly two-thirds (63%) of respondents suggested training of 1 month or less (not including 6% suggesting a 1- to 2-day CME activity), while one-quarter (26%) indicated preference for a 1- to 2-year training. There were no statistically significant differences between professional subgroups in the desired length for BHT.

Interest in Participation in Training

Sixty percent of residents responded “yes” or “maybe” regarding interest in a nonaccredited BH fellowship. This positive response was especially strong (79%) among those planning to start or continue working in the region in the next 5 years, versus those unsure or not planning to work in the region (47%; χ2=18.78; P=.005). Among core faculty working in the border region, 70% reported interest in participating in a nonaccredited BH fellowship as an instructor; the remaining 30% reported “maybe.”

Barriers and Concerns

Residents reported concerns with loss of income during training (67%), need to relocate/proximity to the border (63%), length of training (59%), marketability of skills (29%), current political environment (22%), and redundant material already covered in residency (16%). Loss of income was more concerning to residents from border states (86%) compared to those from border regions (53%) or other regions (59%; χ2=6.91; P=.032). Need to relocate was most concerning to residents living outside border states (52%) or border region (47%; χ2=5.98; P=.05). Marketability of skills was most concerning for those from the border region (53%). Border state participants (21%) and those from other regions (25%; χ2=5.46; P=.065 – trending toward significance) were less concerned with this potential barrier.

Faculty Support

Faculty identified incentives to participate as having protected time (76%), financial compensation (51%), faculty development opportunities (46%), scholarship opportunities or academic advancement (37%), and opportunity for fellows to see patients at the faculty member’s clinical site (23%). They identified increased awareness of issues, increased skills, and retaining providers in the region as positive effects on current programs (Table 2).

|

Effect

|

% In Agreement

|

|

Increased faculty awareness of issues

|

72

|

|

Increase skills of our community to care for these patients

|

70

|

|

Training is more likely to stay and work in these underserved areas

|

70

|

|

Attract interested to current training programs in place

|

53

|

|

Building bridges between community and other health care providers

|

52

|

|

Another faculty member to help with workload

|

26

|

Results of this study indicate a perceived need and sufficient interest in BHT to warrant developing additional experiences. The fact that a higher percentage of respondents from the border region stated the need for such specialized training is noteworthy given that they are presumably familiar with the needs of border-region communities. Interest among learners in border states and regions is encouraging as they are more likely to remain in the area to practice. 17 Interest of trainees outside of the region represents an opportunity to recruit physicians who might not otherwise consider the area. Additional training could improve physician understanding of key regional challenges and potentially increase effectiveness in advocacy and policy whether they practice in the region or not. Encouragingly, faculty working in the region were willing to be involved in BHT and could be incentivized with protected time and academic opportunities.

Survey responses varied regarding type of training, duration, and content often reflecting professional subgroup interests (resident, faculty, or nonfaculty physician) or geographic location (border region, border state, or nonborder). For example, learners who saw themselves working in the border region in the next 5 years were more likely to be interested in 1-2 year fellowship training while others favored shorter-term experiences. Core faculty in border regions favored fellowship or longitudinal residency curriculum, while community providers not involved in teaching expressed interest in CME-type trainings. All groups agreed that language training, medical knowledge, care of asylum seekers, ethics of cross-cultural work and advocacy were the top areas of focus for BHT. Among potential barriers to fellowship training resident listed concerns for loss of income while faculty expressed need for protected time and financial compensation.

Despite these variations, it is clear that the majority of our survey respondents agree that the border region is unique in its challenges and specialized training on relevant topics is needed. Family medicine has always been the specialty most responsive to unique community needs, creating training opportunities to provide family physicians with skills needed to care for their specific communities. Such opportunities have ranged in format and length to also cater to a diverse workforce, whether skills-based workshops during conferences (eg, procedure training), specialty rotations in residency or a postresidency fellowship training like global health, sports medicine or HIV/viral hepatitis family medicine. The results of our study similarly reflect the need to consider offering tiered training options. Brief CME activities could include more discrete topics like asylum forensic exams or orientation opportunities to the region’s unique aspects. Short-term BHT rotations offered by border region residency programs could include topics like appropriate use of interpretation and basic cultural humility. Current border-region residency programs may offer longitudinal experiences, and these residents may benefit from dedicated rotations to increase insight. A 1- to 2-year BHT fellowship may support those interested in mastery of topics requiring immersion (language acquisition) or allow more in-depth training in areas such as cultural humility, barriers to care, and stewardship.

It is important to understand that short-term rotation experiences are limited in scope and are merely introductory in nature. Although some topics may be amenable to such shorter time frames, like barriers to care, migration processes, and stewardship, other components (ie, language training or understanding of binational health systems) would likely require more time investment as suggested by the core faculty in border regions whose survey responses favored fellowship or longitudinal training.

Additionally, short-term training can be ethically challenging both from perspective of exploitation of marginalized communities for learning needs and burden on faculty time and resources at the expense of local trainees who are potentially more likely to serve the local population long-term. These challenges have been battled in the global health setting for decades, and much of the recent literature that has been published about short-term experience in global health (STEGH) expresses concern for exploitation in such experiences. 18, 19, 20 However, benefits of short-term experiences exist, such as educating and exposing learners to important health equity problems that they might otherwise not encounter or recognize. Short-term experiences may be the first step in many physicians’ long-term careers dedicated to serving a particular population. In the case of BHT, this could represent an opportunity to recruit and retain physicians in an area with significant physician shortages. One way to balance these conflicting arguments and to seriously address ethical implications would be to develop strict guidelines similar to WEIGHT guidelines developed in global health. 21 Such guidelines can have firm learner expectations that minimize exploitation and burden and maximize community benefit while providing important learning experiences. For example, border health communities can identify needs such as gathering/providing education materials, assisting with research, participating in advocacy initiatives that can be done during a short-term rotation and could benefit the community limited by human resources in exchange for opportunity to receiving valuable BHT. For example, two authors have worked with visiting residents to support medical care for asylum seekers when the local health care system was overwhelmed by a sudden increase in the number of asylum seekers to the area in 2019.

Similarly, BHT could require prework and a demonstrated commitment before being selected for the learning experience. All of these are possible avenues to balance the desire of short-term experiences with limitations and ethics of such. Development of such guidelines should be the subject of future research.

Our study has several limitations. Use of convenience sampling, while unavoidable in this case, limits generalizability. We cannot generalize what proportion of all FM faculty and residents are interested in BHT; however, those who responded are likely interested. Although we could not calculate possible nonresponse bias, those respondents with sufficient interest in BHT suggest there may be value in developing such experiences. Survey data is susceptible to self-reported information bias possibly influenced by social desirability in favoring BH among respondents. Respondents who indicated that BHT was not necessary were not directed to answer any remaining questions in the survey, thus the survey did not capture the perspectives of those respondents.

Future work in this area should include additional data collection from nonphysician faculty, community agencies, and patients to obtain a more diverse perspective on training needs. Currently, two authors are piloting a BH rotation within the border region both for local residents and residents outside the region. They will evaluate and modify the curriculum over the next 2 years. This may serve as a foundation for development of further BHT opportunities. Further exploration of the BHT offered by border region residency programs is also needed as location alone within the border region does not indicate residents will receive or recognize components of BHT. Additional studies would be helpful to determine if there is true retention of residents who train in the border region.

This study explored perceived need and interest in BHT in FM. While the study does demonstrate a perceived need for and interest in increased opportunities for BHT in FM, it also elucidates questions that require further research. In particular, the study highlights the tension between a shorter-term desired length of training and the ethics of short-term training as debated in the global health arena. The results of this study suggest interest and offers a starting point, but also indicate a need for further research and evaluation of BHT opportunities and experiences.

Footnote

* Number of intern positions at one program unavailable.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: This study was presented as:

Fitzsimmons-Pattison D, Scott MA, Valdman O. Border Health Training: Is There a Need? Presentation at AAFP Global Health Summit. Albuquerque NM; October 10, 2019.

Financial Support: Limited travel money was supplied through the Family Health Center of Worcester Global Health Fellowship.

References

-

-

Carrillo G, Uribe F, Lucio R, Ramirez Lopez A, Korc M. The United States-Mexico border environmental public health: the challenges of working with two systems. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2017;41:e98.

-

Starr H. International Borders: What they are, what they mean, and why we should care. SAIS Rev. 2006;26(1):3-10. doi:10.1353/sais.2006.0023

-

-

-

-

McEwen MM, Pasvogel A, Elizondo-Pereo R, Meester I, Vargas-Villarreal J, González-Salazar F. Diabetes self-management behaviors, health care access, and health perception in Mexico-US border states.

Diabetes Educ. 2019;45(2):164-173.

doi:10.1177/0145721719828952

-

-

-

Watt GP, Vatcheva KP, Beretta L, et al. Hepatitis C virus in Mexican Americans: a population-based study reveals relatively high prevalence and negative association with diabetes.

Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144(2):297-305.

doi:10.1017/S0950268815001247

-

-

Carillo G, Uribe F, Lucio R, Lopez A, Korc M. The Unite States-Mexico border environmental public health: the challenges of working with two systems. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2017;41:1-6.

-

Rodriquez-Saldaña J. Challenges and opportunities in border heath, preventing chronic disease public health research. Practice and Policy. 2005;2(1):1-4.

-

Zhang X, Lin D, Pforsich H, Lin VW. Physician workforce in the United States of America: forecasting nationwide shortages.

Hum Resour Health. 2020;18(1):8.

doi:10.1186/s12960-020-0448-3

-

-

Fagan EB, Finnegan SC, Bazemore AW, Gibbons CB, Petterson SM. Migration after family medicine residency: 56% of graduates practice within 100 miles of training. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(10):704.

-

Ferguson WJ, Cashman SB, Savageau JA, Lasser DH. Thirty years of family medicine residency training: characteristics associated with practice in a health professions shortage area. Fam Med. 2009;41(6):405-410.

-

Crump JA. Sugarman J. Ethical consideration for short-term experinces by trainees in global health. JAMA. 2008;300(12):1456.

-

Tracey P, Rajaratnam E, Varughese J, et al. Guidelines for short-term medical missions: perspectives from host countries.

Global Health. 2022;18(1):19.

doi:10.1186/s12992-022-00815-7

-

Melby MK, Loh LC, Evert J, Prater C, Lin H, Khan OA. Beyond medical “missions” to impact-driven short-term experiences in global health (STEGHs): ethical principles to optimize community benefit and learner experience.

Acad Med. 2016;91(5):633-638.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001009

-

Crump JA, Sugarman J. Ethics and best practices for training experiences in global health Am J Trop. Med Hyg (Geneve). 2010;83(6):1178-1182.

There are no comments for this article.