Students in the first 2 years of medical school at the University of Minnesota Medical School Duluth Campus have had clinical studies integrated into their education since the campus began in 1972.1 In early spring of 2020, the SARS-CoV-2 viral pandemic resulted in the unanticipated and abrupt cessation of these early clinical experiences for the students. Notably, this included the longitudinal clinical placements with rural family physicians that had previously punctuated the preclinical years. Meanwhile, the institutional goals—fostering professional support for family medicine, Native American, and Rural Health—remained unchanged. This report describes the curriculum developed in April-May of 2020 to supplant the experiential rural preceptorships with virtual learning modules.

SPECIAL ARTICLE

Transforming Rural Family Medicine Curriculum From Experiential to Virtual: A Response to COVID-19 Limitations

James G. Boulger, PhD | Emily Onello, MD

PRiMER. 2020;4:19.

Published: 9/15/2020 | DOI: 10.22454/PRiMER.2020.343294

Cessation of all classroom and clinical activities in the spring of 2020 for first- and second-year medical students at the University of Minnesota Medical School Duluth campus both forced and enabled revision of rural medicine instruction and experiences. Creatively utilizing rural family physicians and third-year rural physician associate medical students to interact with first-year students virtually in a number of areas and using electronic connectivity enabled the institution to continue to emphasize rural medical health issues with the students.

Prior to the 2019 academic year, Duluth medical students enrolled in the Rural Medical Scholars Program (RMSP) that placed students in family medicine clinics in rural and small communities for 1-week intervals occurring over the first 17 months of their training.2 To pass the required RMSP course, each student completed a total of five week-long visits to the same rural community under the guidance of the same rural family physician preceptor. This punctuated longitudinal design allowed the student to revisit a rural practice as their clinical skills and knowledge grew.

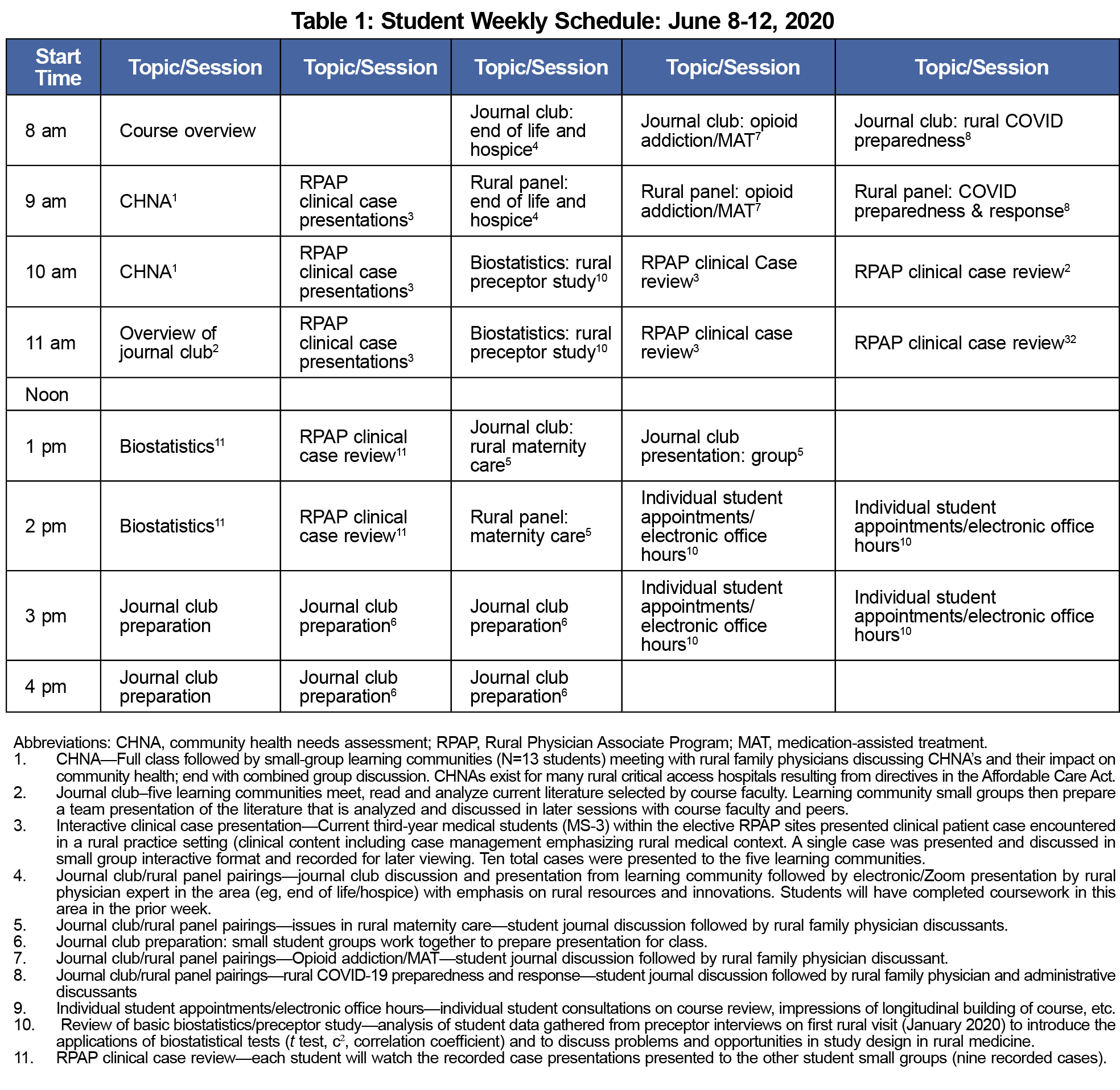

In response to the COVID-19-related removal of students from clinical rotations, the RMSP course directors labored to bring some of the rural components to the virtual university classroom curricular time. The curricular time that students would have been on site with a rural family physician was replaced with a new curricular scheme, all delivered electronically (typically by Zoom). The new curricular elements are described and footnoted in Table 1.

In planning the journal club/rural panel sessions, course faculty identified themes around which the assigned readings and rural panel discussions would be constructed. Directors chose themes on the basis of their rural relevance and impact as well as timeliness and support for course objectives. The themes for 2020 were:

- Rural hospice and end-of-life care

- Rural obstetrical services and maternity care

- Rural approaches to opioid use disorder and medication-assisted treatment

- COVID-19 rural disaster preparedness and response.

External panelists invited to the topical discussion sessions were selected for their direct professional experience with the topic and theme of their respective sessions. For example, a critical-access hospital chief executive officer was invited to the COVID-19 session to discuss how his organization had prepared and responded to the unanticipated COVID-19 outbreak in a small Minnesota community.

The curricular modifications described enabled the fullest cooperation and interaction with the first-year medical students and some key rural health providers and thought leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sessions were designed to align with existing RMSP course objectives. Evaluation was via student surveys, reflective writing assignments, exam performances in areas covered, and in end-of-course private consultations with students.

As expected, course evaluations were positive but not as favorable as previous years’ experiences in direct clinical care in rural settings. Students commented that their preference would be for direct community base experiences, but were appreciative of the efforts and adjustments required due to the pandemic. The overall course evaluations were high, with the student responses to the query of “Overall, I have acquired a basic understanding of rural health” averaging 4.424 (scale: 5=strongly agree), where the virtual sessions were rated an average of 3.618 on the same scale.

Successful instruction on rural heath material via teleconferencing and Zoom presentations was incorporated into the first-year medical curriculum with marked success. Student evaluations affirmed the value of these sessions but they were not evaluated as positively as direct rural clinical experiences with family physicians.

References

- Boulger J, Onello E. Family medicine preceptorships for first year medical students: durable educational value amid Healthcare transformation. J Reg Med Campuses. 2018;1(3). doi:10.24926/jrmc.v1i3.1102

- Beehler S, Boulger J, Friedrichsen SC, Onello EC. Teaching community health needs assessment to first year medical students: integrating with longitudinal clinical experience in rural communities. J Community Health. 2019;44(4):784-789. doi:10.1007/s10900-019-00651-8

Lead Author

James G. Boulger, PhD

Affiliations: University of Minnesota Duluth Campus

Co-Authors

Emily Onello, MD - University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth Campus

Corresponding Author

James G. Boulger, PhD

Correspondence: University of Minnesota Medical School Duluth- Biobehavioral Health; Family Medicine, 1035 University Drive, Duluth, MN 55812. 218-726-8895

Email: jboulger@d.umn.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.