Background and Objectives: During the COVID-19 pandemic, medical students were unable to participate in clinical learning for several weeks. Many primary care patients no-showed to appointments and did not receive care. We implemented a telephone outreach program using medical students to call primary care patients who no-showed to appointments and did not receive care.

Methods: A brief plan-do-study-act cycle was used to establish protocols and supervision for the phone calls.

Results: In the first 5 weeks, of 3,274 scheduled patients there were 426 no-shows; 309 received outreach from students. We developed protocols for supervision, routing, and triage.

Conclusion: It is feasible and educationally valuable to collaborate with students to reach patients who are at home due to the pandemic. Other practices could adapt this tool in similar situations.

Primary care practices treat medical problems before they become severe. Past studies, for example, have documented the impact of primary care on decreasing hospital admissions for ambulatory-sensitive conditions.1 Providers’ ability to do this is hampered when patients no-show to appointments.2,3 The overall no-show rate in primary care was reported at 23% in a meta-analysis.2 Researchers note a correlation between no-shows and emergency department visits for all patients,3 especially diabetic patients.4

In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic began in the Northeastern United States. Most states issued stay-at-home orders5 and many patients avoided health care settings6 for fear of contracting the coronavirus. Medical students were unable to participate in clinical learning.

We implemented an initiative to have students reach out by phone to the patients who no-showed in the first 5 weeks of the pandemic. We sought effective ways to (a) teach triage and management of phone calls, and (b) document communication with patients and link them back to primary care.

Our clinic is a family medicine teaching practice in Pawtucket, Rhode Island with approximately 12,000 patients. In 2019 there were 30,000 visits, about 600 per week. The clinic is staffed by 47 providers (37 residents).

In Rhode Island, schools were closed on March 13, 2020.7 The Warren Alpert Medical School at Brown University also advised students to stay at home and not participate in clinical rotations. Medical student rotations were impacted; some used virtual learning.

We proposed an initiative for medical students familiar with the clinic and the electronic medical record (EMR). They reviewed the EMR from home, finding all the no-shows from March 13 through April 17 (these patients were deemed most likely to have active health issues), and reached out to these patients by phone. We did a rapid-cycle plan-do-study-act (PDSA)8,9 over 2 days during which all the calls were precepted with the medical director in real time and we took notes to optimize subsequent calls. The students then called the remaining patients over 2 weeks.

We collected data on the types of calls that came up and how much supervision they required, as well as the students’ learning curve about formatting and routing the notes. We also collected data on the number of scheduled appointments, number of no-shows, and number of patients called by each student from looking at the schedule page of the EMR and the students’ notes.

We consulted with the institutional review board at our institution, which determined that this project did not meet the federal definition of human subjects research.

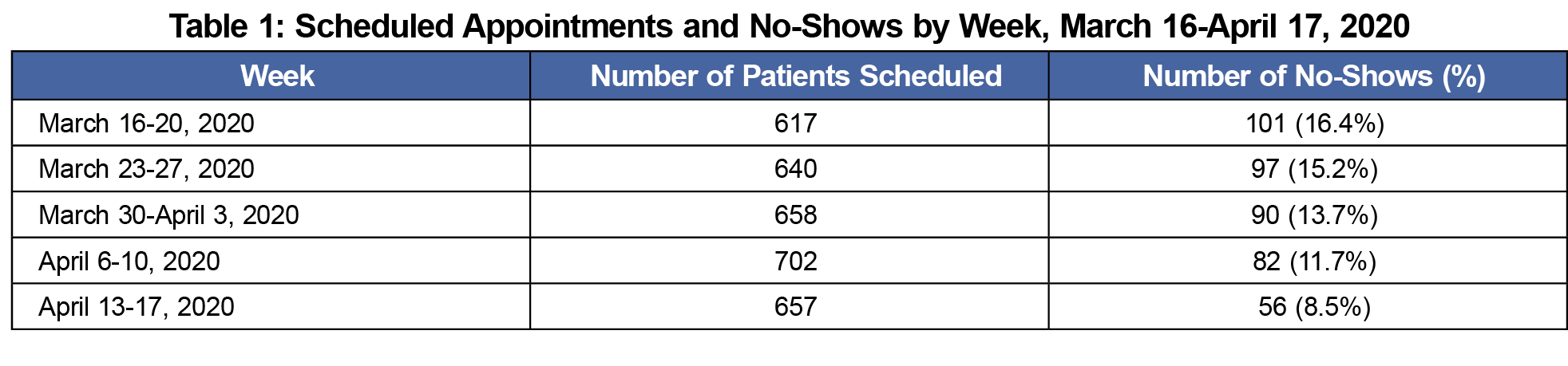

Between March 13, 2020 and April 17, 2020, 3,274 patients were scheduled for in-person visits at our clinic; 426 of them no-showed during that time, the rate decreasing from 16% to 8% over time (Table 1).

Table 2 shows the output from the rapid-cycle PDSA in the first 2 days of the project. We focused on process measures to rapidly teach, develop, improve, and implement a short-term intervention. We identified types of problems (eg, patients who need appointments vs simply needed refills or labs), note routing issues, and follow-up issues.

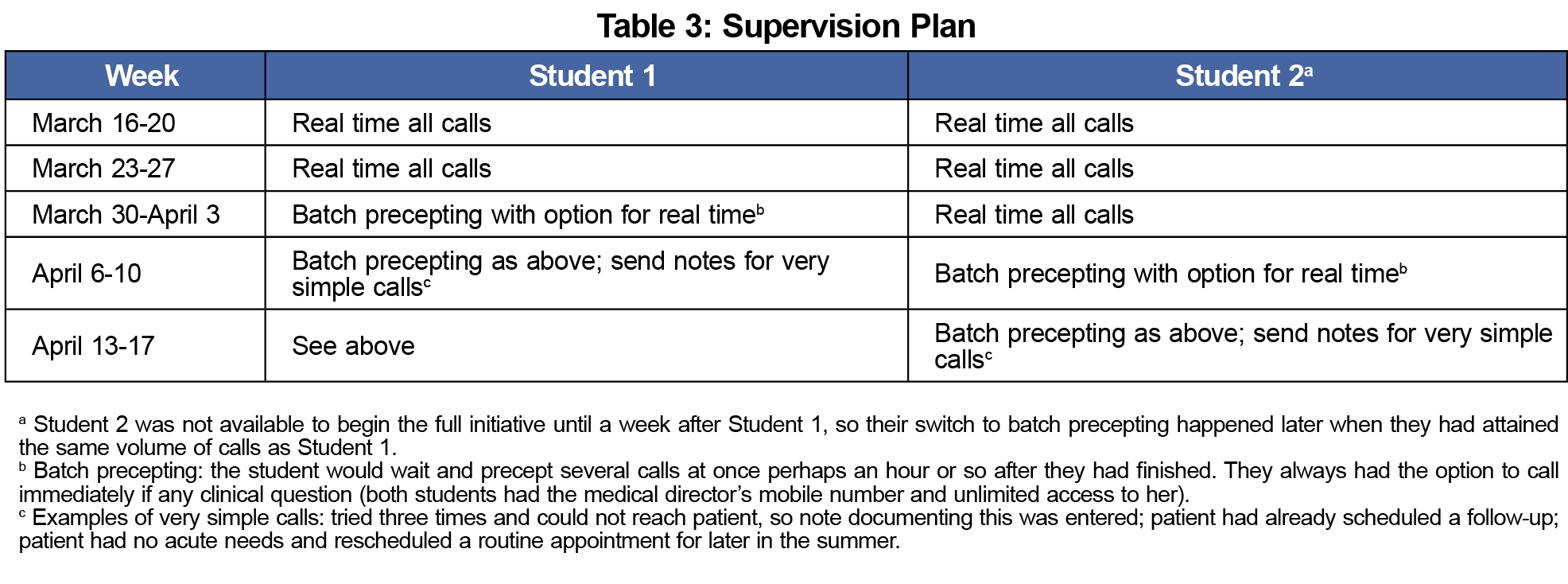

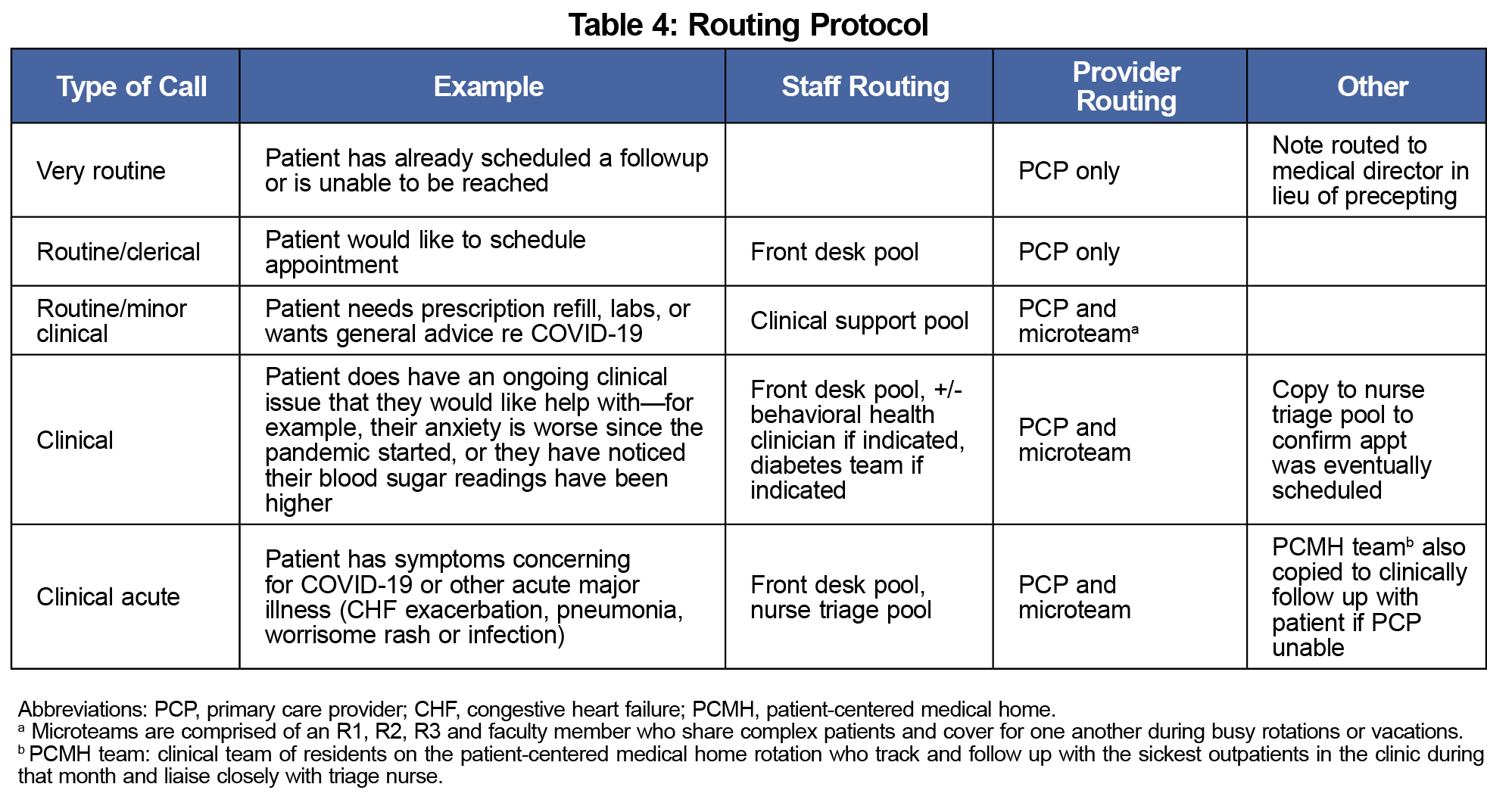

Table 3 shows the supervision plan. While the students were not intended to exercise clinical judgment over the phone, we wanted to be sure they were adequately supported and that patient safety was prioritized. Table 4 details the routing protocol for calls. Feedback from providers indicated that the routing was overly cautious (many providers copied), but we felt that was reasonable given the uncertainty regarding who might be ill/quarantined and unavailable to do clinical work.

Table 5 shows data on the no-show volume and phone call volume. This shows an overall snapshot of the work done by the students and the amount of time it took. Most important was the educational aspect of this project. While all the learning occured on the job, the students were asked to reflect on what they learned/gained from the project afterward (Table 6).

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused many changes in the process of providing health care.10 Most of these changes dealt with the care of patients with COVID and suspected COVID11; secondarily, some changes prioritized patient safety, for example cancelling elective surgery.12

In our clinic, we also worried about unintended consequences of COVID unique to primary care practices11,13—uncontrolled chronic illnesses, delays in testing or diagnosis for patients undergoing workups, and delayed/postponed routine screenings. The work from this initiative is only a first step in developing guidelines to pause and resume routine/nonurgent primary care should another pandemic occur, or any issue that forces patients away from in-person care temporarily (eg, a weather event, an environmental disaster).

The key element in our initiative was the collaboration with medical students. Similar to other ambulatory clinics and initiatives,14,15 incorporating medical students provided learning opportunities for students to engage in interdisciplinary patient care, strengthening our efforts to reach vulnerable patient populations. We were fortunate to recruit two students for the initial phase who understood our clinic workflow, but the project could be replicated in the future with different volunteers. An important note is that the project was initially labor-intensive for the supervising faculty (here, the medical director). A more sustainable model might include the students precepting calls with whichever faculty member was on duty at the clinic.

Future directions for this work include the expansion of ability to include students in alternate workforce deployment in primary care settings, attention to vulnerable populations during similar emergencies, and the safest and most effective ways to resume in-person care. It would also be interesting to compare patients who received a telephone intervention like this with those who did not on outcomes such as emergency department visits. For this project, we primarily focused on the educational experience and the learning and process outcomes above.

It remains to be seen whether this intervention will result in improved long-term outcomes in our patients. However, the execution and setup of this initiative was thought to be potentially of value to other settings with learners, especially since the pandemic is not yet over. We anticipate that over the next several months, more recommendations and ideas will be developed as a result of creative use of primary care resources in times of crisis.

References

- Parchman ML, Culler S. Primary care physicians and avoidable hospitalizations. J Fam Pract. 1994;39(2):123-128.

- Dantas LF, Fleck JL, Cyrino Oliveira FL, Hamacher S. No-shows in appointment scheduling - a systematic literature review. Health Policy. 2018;122(4):412-421. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.02.002

- Nguyen DL, Dejesus RS. Increased frequency of no-shows in residents’ primary care clinic is associated with more visits to the emergency department. J Prim Care Community Health. 2010;1(1):8-11. doi:10.1177/2150131909359930

- Nuti LA, Lawley M, Turkcan A, et al. No-shows to primary care appointments: subsequent acute care utilization among diabetic patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):304. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-12-304

- Kaiser Family Foundation.When stay-at-home orders went into effect (slide). https://www.kff.org/other/slide/when-state-stay-at-home-orders-due-to-coronavirus-went-into-effect/. Published April 9, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2021.

- Mehotra A, Chernew M, Linetsky D et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on outpatient visits: A rebound emerges. The Commonwealth Fund. www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/apr/impact-covid-19-outpatient-visits. Published May 19, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2021.

- Anderson P. The month our lives changed. Providence Journal. www.providencejournal.com/news/20200403/month-our-lives-changed. Published April 3, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2021.

- Cleary B. Supporting empowerment with Deming’s PDSA cycle. Empowerment in organizations. June 1995; 3(2). doi:10.1108/09684899510089310

- Crowfoot D, Prasad V. Using the PDSA cycle to make changes in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 2017;10(7):425-430.

- Dewar S, Lee PG, Suh TT, Min L. Uptake of Virtual Visits in A Geriatric Primary Care Clinic During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020 Jul;68(7):1392-1394. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16534. Epub 2020 May 15.

- Krist AH, DeVoe JE, Cheng A, Ehrlich T, Jones SM. Redesigning primary care to address the COVID-19 pandemic in the midst of the pandemic. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(4):349-354. doi:10.1370/afm.2557

- Ong MT, Ling SK, Wong RM, Ho KK, Chow SK, Cheung LW, Yung PS. Impact of COVID-19 on orthopaedic clinical service, education and research in a university hospital. J Orthop Translat. 2020 Nov;25:125-127. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2020.08.001.

- Verhoeven V, Tsakitzidis G, Philips H, Van Royen P. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the core functions of primary care: will the cure be worse than the disease? A qualitative interview study in Flemish GPs. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e039674. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039674

- Doolittle BR, Richards B, Tarabar A, et al. The day the residents left: lessons learnt from COVID-19 for ambulatory clinics. Family Med Comm Health; 2020:8.

- Office EE, Rodenstein MS, Merchant TS, Pendergrast TR, Lindquist LA. Reducing social isolation of seniors during COVID-19 through medical student telephone contact. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(7):948-950. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2020.06.003

There are no comments for this article.